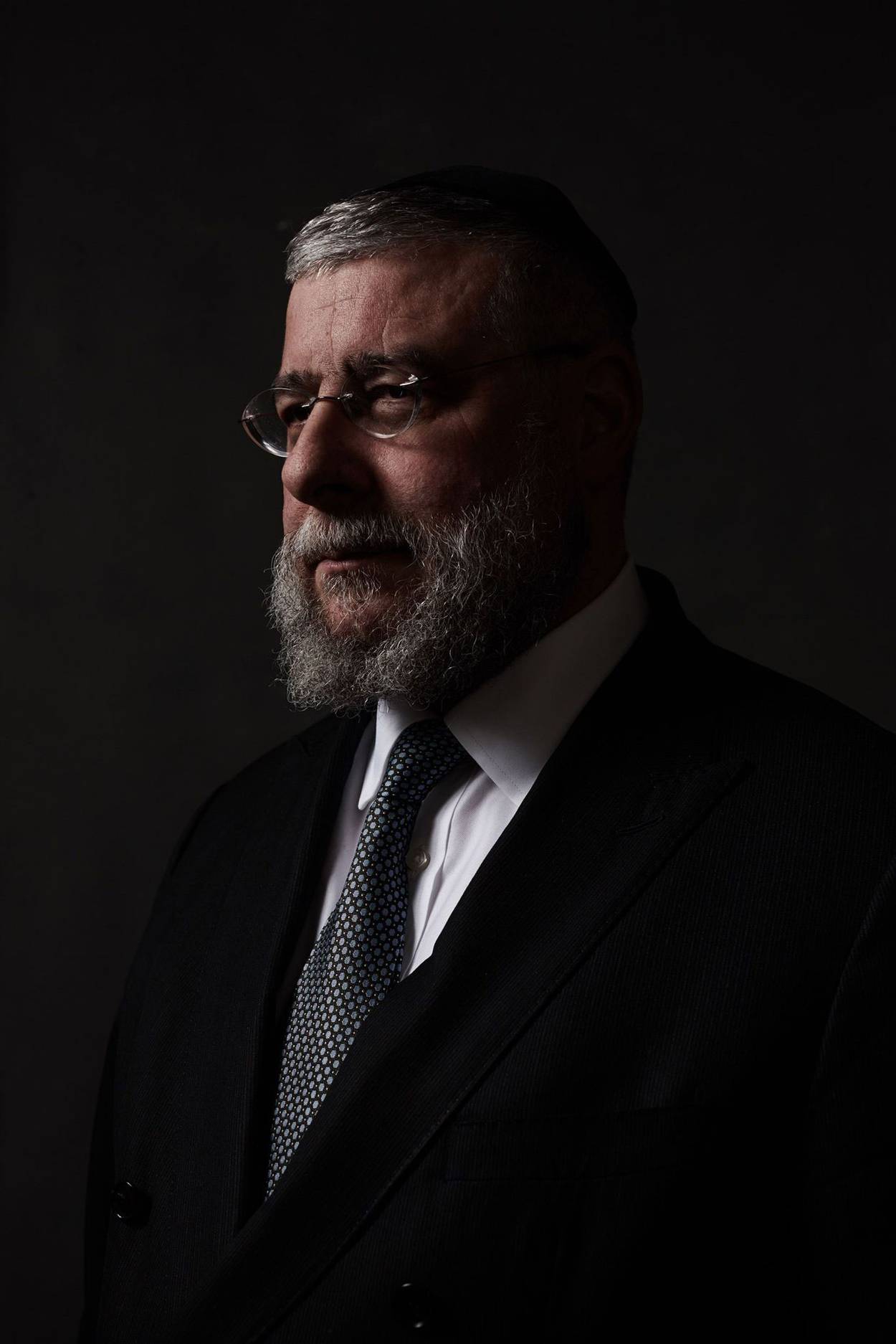

Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt sat at the desk of his Jerusalem office on a scorcher of a July day. Wearing a suit and tie, his monogrammed shirt cuff peeking out, Goldschmidt seemed immune to the intense heat—a quality hinting at how, of the 33 years he served as Moscow’s chief rabbi, he might have weathered the last 22 during the presidency of Vladimir Putin.

But everyone has a boiling point, and Goldschmidt reached his when Russian authorities pressured him and other religious leaders to support Putin’s war on Ukraine that began on Feb. 24, 2022.

Goldschmidt publicly opposed the war, departed the country, resigned his pulpit in Moscow’s Choral Synagogue, and resettled in Israel, leaving behind Russia and his and his wife Dara’s work: regenerating the capital’s Jewish community following seven decades of Soviet repression and building an orphanage, a school, and a kollel—an academy for Talmud study.

Last summer, he urged Russia’s Jews to leave the country. This June, the country’s Justice Ministry labeled him and several other visible opponents of the war “foreign agents,” affixing metaphorical targets to their backs.

Nearly a year-and-a-half into Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Goldschmidt sees his condemning of the war and emigrating as correct. He’d been silenced “for all the years under Putin,” he said. “I wasn’t able to say a word.”

Goldschmidt said he recognized the risk of opposing Putin. He cited Ecclesiastes 3:7: “A time to keep silent and a time to speak.” The time, he said, was right to speak.

“The moment I knew that I’d be criticizing the war, that I’d be against the Russian government, I knew that I would have to leave my post as chief rabbi of the city, because the government would use its clutches to get me out or to close down the community,” said Goldschmidt. “It was a decision I knew would have to result in my resignation in order not to endanger the community.”

But leaving and urging others to follow didn’t come easily. Goldschmidt said he spoke with friends, colleagues, and community leaders in Russia and abroad. He researched rabbis’ contemporaneous responses to anti-Jewish agitation, pogroms, and the Holocaust. He sought clarity for what gnawed at him: Was the situation as dire as he thought?

“I was questioning myself in the beginning if I did the right thing or not by leaving. But as the situation evolved, there was no other way,” he said. “I just feel that there’s a moment when a communal leader has to tell his people that the future is not as bright as it was and we should think of other options.”

As to what set his decision-making in motion, Goldschmidt recalled the events of 2022 this way: “I went to sleep in Moscow on Feb. 23 and woke up in the morning in Tehran—a different country with a different political system. I realized that under this new political reality, it would be impossible to speak for a Jewish future. It became almost impossible for a Jewish community to function.”

It was a stunning end to a lengthy tenure that began when a classmate from his native Switzerland told Goldschmidt—who, while living in Baltimore, had been ordained and earned a master’s degree in computer science—that Moscow’s Jewish community wished to hire a rabbi.

When Goldschmidt, his wife, and their two small children—the couple would have seven; three now live in Israel and four in the United States—arrived in 1989, Russia was the behemoth of a Soviet Union at once disintegrating and evolving under the freedom-minded reforms begun by the glasnost and perestroika policies of the USSR’s leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, and later extended by Russia’s president, Boris Yeltsin.

By reversing Russia’s democratization and, later, invading Ukraine in 2014 and again in 2022, Putin has yanked the country back to its Soviet days, Goldschmidt said.

That, he said, constitutes a physical and demographic threat to Russia’s Jews, whose numbers aren’t easily pinned down. (Goldschmidt cited estimates ranging from 90,000 to 350,000.) Approximately 100,000 Jews now seek to leave Russia, in addition to 100,000 who have already left since the war began, Goldschmidt said.

Goldschmidt in the Choral SynagogueEli Itkin

Rabbis arriving from abroad to serve Russia’s Jewish communities “are being stopped at the borders” and harassed, he said, their smartphones inspected and possibly implanted with eavesdropping devices, and the philanthropic funding of Jewish institutions has shriveled due to Jewish businesspeople emigrating.

“The fact that at any communal gathering, you have two or three characters who show up uninvited—you know right away these are FSB characters,” Goldschmidt said, referring to the security service that succeeded the KGB. “We are back to the Soviet era. The question is: Do Jews want to live in the Soviet Union? The answer is no.”

As the situation further deteriorated last summer, Goldschmidt said, he and other Jewish officials grew concerned by two major developments: a possible military mobilization of Russian men, including Jews; and the government’s closing of the Jewish Agency, a Jerusalem-based organization that helps Jews in scores of countries to prepare to move to Israel.

Russia’s Jews, he sensed, would, as in the Soviet era, be squeezed both if they remained and attempted to leave.

That’s when Goldschmidt called on them to emigrate.

“I feared that as a result, it’s going to be much more difficult to cross the border,” he said.

Goldschmidt’s son Benjamin, a congregational rabbi in Manhattan, considers his father “courageous” for urging Russian Jewish emigration. His parents had “put their whole lives” into rebuilding Moscow’s Jewish infrastructure, but “a rabbinic judge must rule based on the facts in front of him,” he said. “There’s no rabbinical commandment that says you have to live in Russia.”

“We Jews have to be optimists,” Pinchas Goldschmidt said when asked whether he can imagine living again in Moscow. “One day it’ll be possible to return, but when it is I don’t know.”

Returning his pulpit is complex, too.

“We’re going to have to see what percentage of the community is still there. Number two, what the new political realities are, the economic realities,” he said. “Based on that, it is going to be possible to make an educated decision.”

Meanwhile, in Israel, he remains busy. He leads classes online on Jewish topics, including in Russian. He’s writing two books: on how Jewish law views civil marriages and on his time in Moscow. He visits his father, Sol, 91, a retired businessman who lives nearby and has dementia. And he spends much of his time in Munich, the headquarters of the Conference of European Rabbis, which he serves as president.

In that role, Goldschmidt opposed Scandinavian countries’ efforts to outlaw circumcision and kosher slaughter.

“Over the years, he hasn’t been afraid to speak his mind,” said Mark Levin, the Washington, D.C.-based CEO of the National Coalition Supporting Eurasian Jewry, who has known Goldschmidt since before the latter served in Moscow.

The issues on which Goldschmidt has made an impact both in Moscow and with the CER is “a long list,” Levin said.

“He’s one of the—I say this in all sincerity—important international figures in Jewish life in the last 20-something years,” Levin said. “He’s a rare combination of a diplomat and an advocate. It demonstrates his ability to meet and address all challenges.”

Now, Moscow’s Jews face the new reality without their spiritual leader, although synagogues, the Russian Jewish Congress, and other key organizations continue to function. Goldschmidt maintains contact with many Muscovites, while others, he said, “are afraid to talk to me” now.

“The fear of Big Brother—this has come back. It’s part of life in Russia today,” Goldschmidt said. He’s less concerned by “street antisemitism,” and more by government pronouncements, such as Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in May 2022 comparing Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to Hitler and claiming that Hitler was partially Jewish.

After Lavrov’s statement, Goldschmidt said, he received reports from Moscow of “an avalanche” of antisemitic posts on social media.

“The system, which became so anti-Western and so insular—it’s impossible that the system isn’t going to bring with it manifestations of antisemitism,” he said. “Putin is not an antisemite. But the moment there’s a sign coming from above that from now on it’s [antisemitism] allowed, I would be very worried about the security of Jewish institutions and every single Jew.”

He’s led fundraisers to assist Ukrainian Jews and visited Ukrainian Jewish refugees in Romania, Hungary, Austria, and Germany. Zelensky invited him to Ukraine, and he may lead a CER delegation there.

Its goal would be “very simple,” Goldschmidt said: “to support the Jewish community.”

“The great tragedy of this war,” said Goldschmidt, “is that two Jewish communities are being destroyed: the Jewish community of Russia and the Jewish community of Ukraine.”