Getting Over Coco

Coco Chanel, the subject of several children’s books that overlook her dark side, was a vile Nazi sympathizer. Maybe we should be teaching kids about other designers instead.

By my count, there have been five (5) picture-book biographies of Coco Chanel published since 2011. This is five (5) too many.

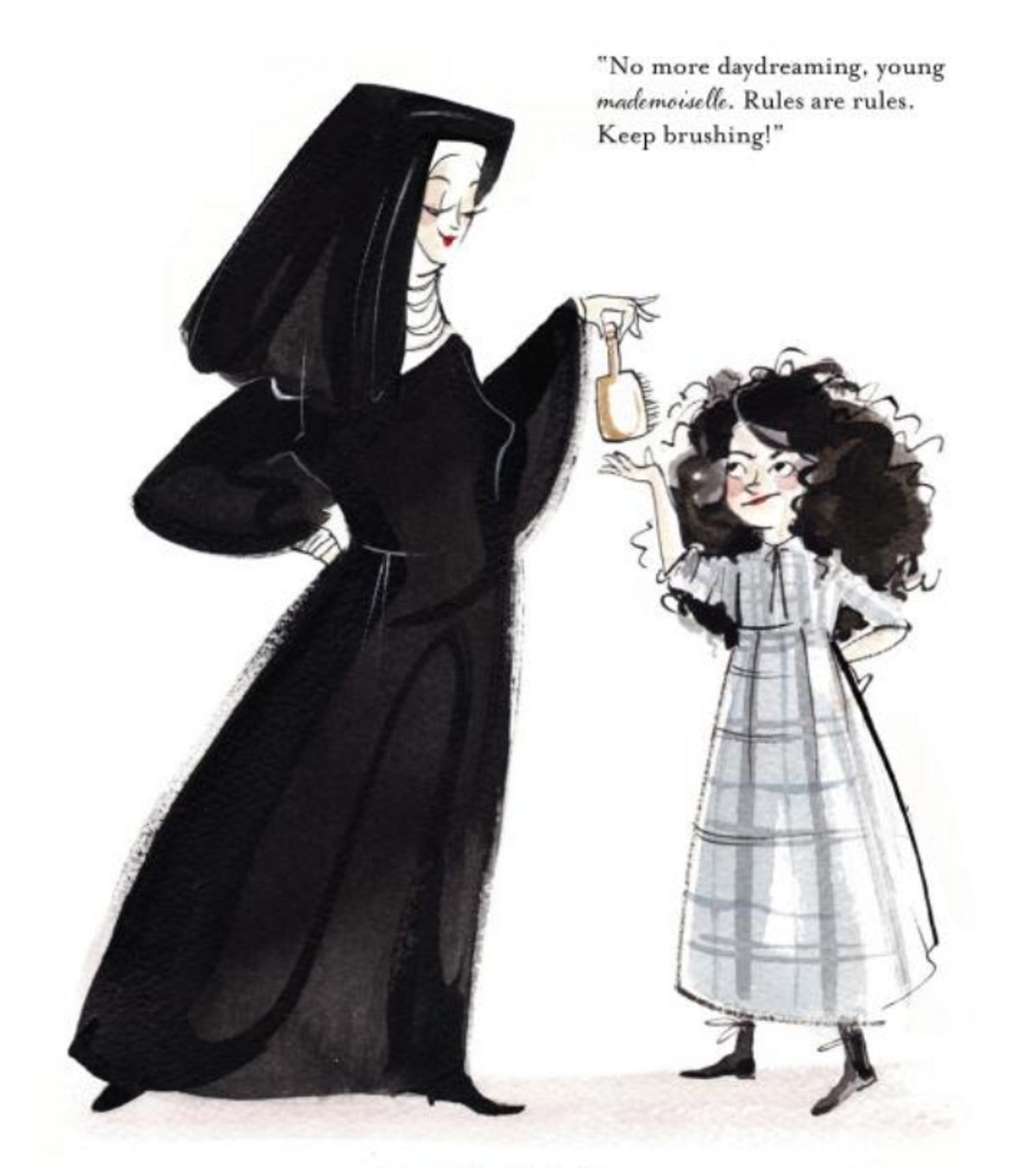

To be fair, Along Came Coco by Eva Byrne (2019); Coco Chanel by Al Berenger (2018); Coco Chanel by Isabel Sanchez Vegara, illustrated by Ana Albero (2016); Coco and the Little Black Dress by Annemarie van Haeringen (2013); and Different Like Coco by Elizabeth Matthews (2011) each have something to recommend them. Byrne’s book has lively, glam, fashion-illustration-inflected art, sure to entice Fancy Nancy fans. Berenger’s book offers simple subject-predicate sentences and Disney-esque visuals. Vegara’s book (part of the Little People, Big Dreams biography series for very young kids) has ultrasimple, toddler-friendly text and equally approachable, big-eyed, naif llustrations. Van Haeringen’s entry has witty, stylish layout and design and a delicious Quentin Blake-ish vibe; Matthews is the most thoughtful storyteller of the bunch, albeit with the weakest art.

Here’s the thing, though: Coco Chanel was a vile person. She loathed Jews. She had a love affair in the early 1940s with a Nazi officer during the occupation of Paris; she was accused of collaborationism after the war. She took credit for other people’s ideas (straight-cut chemise dresses, the abandonment of the corset, pants for women, and bobbed hair were all the innovations of Paul Poiret; Chanel claimed them as hers). She presented herself as a self-made woman, even as her business was bankrolled and shops purchased for her in prime locations in fancy resort towns by a succession of wealthy paramours. She lied incessantly: about her childhood in a Catholic orphanage, her work, her age. (At 27, she claimed to be 18.) She was nasty to her models and employees.

But only one of the picture books comes close to wrestling with any of these unpleasant facts. And it only wrestles with one of them. Different Like Coco notes: “[Coco] constantly rearranged and romanticized the facts of her life story. She would even tell lies in confession!” Garsh! (Along Came Coco’s even more mild take on Chanel’s behavior: “Coco was not so fabulous at following the rules … which was a pity, because nuns love rules.” Way to blame the nuns.)

Maybe—and bear with me here—maybe some people are not great subjects for picture books for small children. Maybe we shouldn’t snip-snip-snip away at historical truth as if it were an overly fussy petticoat. Maybe we shouldn’t craft a nice, clean-lined narrative about a poor little motherless girl who grew up, reinvented fashion, and became the wealthy toast of the town, when the real girl in question became a deeply unpleasant woman.

Which is not to say that we can’t write children’s books about complicated figures! Susan Goldman Rubin’s Coco Chanel: Pearls, Perfume, and the Little Black Dress is a 2018 chapter book biography aimed at middle-grade readers that doesn’t sacrifice nuance for convenient, and false, simplicity. Rubin is a master of the genre: She’s written complex yet readable nonfiction about Brown v. Board of Education, the quilters of Gee’s Bend, and the art of the children of Terezin. Her middle-grade book about Leonard Bernstein was on Tablet’s Best Jewish Children’s Books list in 2011, and her young adult book about Mississippi’s Freedom Summer of 1964 was on Tablet’s list in 2014. She’s a star.

Rubin’s book is still a fun read, but it’s aimed at a slightly older audience, one better able to deal with complexity. Rubin tells readers of Chanel’s competitiveness with Poiret, Schiaparelli, and Dior. She goes into detail about the contrast of Schiaparelli’s colorful, surrealist designs with Chanel’s minimalist little black dresses, and serves up the tea about Chanel and Schiaparelli sniping at one another. Coco witheringly called Schiap “that Italian who’s making clothes.” Schiap sniffily called Coco “that dreary little bourgeoise.”

We learn a bit of context for her hatred of Jews: the teachings of the Catholic orphanage she grew up in, the backdrop of the Dreyfus affair. But we also learn she was willing to work with Jews when they could help her career: The richest parfumiers in France were the Wertheimer brothers, who became instrumental in the creation of Chanel No. 5. She loathed France’s left-wing Jewish premier ,Leon Blum, who “sought reforms such as paid vacations and unemployment insurance,” Rubin writes. “Wealthy conservatives like Coco were terrified about how their businesses selling luxury goods would be affected by the promised changes.”

Chanel refused to negotiate when her workers went on strike (Schiaparelli’s workers stayed on the job, because she paid them well), but Chanel even turned a bitter labor dispute into a self-aggrandizing story: “Later, Coco reinvented the episode as ‘cheerful and delightful,’” Rubin writes. “According to her story, she asked the strikers what they wanted, and they replied, ‘We don’t see enough of Mademoiselle. Only the models see her.’” Chanel concluded, “’It was a strike for love … a strike of the yearning heart.”

When Germany invaded, Chanel abruptly shut her business down. She said that this wasn’t the time for fashion, though Rubin posits that she may have just wanted out of the competition with Schiaparelli … who was winning. When the French government asked her to “show a little patriotic spirit” by creating new uniforms for women officers and nurses, Chanel’s response was: “You must be joking!” Rubin writes that she considered this gig beneath her.

Rubin also notes, pointedly, “Like many French citizens, she resented Jewish refugees living in France during the 1930s.” Chanel tried to gain sole control of the perfume business by saying it was “the property of Jews” and “legally abandoned.” (It wasn’t—the Wertheimers had left a non-Jewish friend and colleague in charge before fleeing France.) She shacked up with a Nazi, yet managed to avoid the fate of other Frenchwomen with German boyfriends, who “had their heads shaved and were paraded through the streets past jeering mobs”: When Paris was liberated, she savvily began giving away free Chanel No. 5 to American GIs to give to their girls back home … so that they’d protect her from her compatriots, who viewed her (and to a degree, still do) as a collaborationist.

Rubin knows how much fun it is to read about Chanel’s horridness. But she also gives the designer a lot of credit: Chanel was gifted at construction, at placing pockets flatteringly and making hemlines lay just so via sewn-in weighted chains. She could always make something out of nothing (reworking cheap hats from Galleries Lafayette into couture creations; creating a rage for lightweight dresses made from discounted and dyed men’s underwear fabric; elevating the idea of costume jewelry when she herself couldn’t afford the real thing). Rubin also points out the sexism and ageism Chanel faced after the war.

Everything in the text is substantiated in the back matter (which is another problem with picture books—how do you prove to little kids that your story is true?); Rubin provides sources for every quote, as well as suggestions for further reading.

The problem with picture books about Chanel isn’t just that they’re reductive to the point of fiction and turn a problematic figure into a blemish-free heroine. It’s that telling Chanel’s story over and over means we’re not telling other stories. As my genius librarian friend Leila Roy points out, in a rave review of a marvelous new picture book about Congresswoman Barbara Jordan: “No offense to Amelia Earhart and Ada Lovelace, but there are a lot lot lot lot LOT of other interesting and inspiring historical figures to read about.” Jewish addendum: There are also many interesting Jewish women who are not Anne Frank.

Picture-book writers, I challenge you: Please give me a snazzy picture book biography of a Jewish fashion designer. Come on, we created the schmatte business! How hard can it be? Yet the only one I know of is Levi Strauss Gets a Bright Idea, a 2011 book by Tony Johnston, illustrated by the terrific Stacy Innerst (whose illustrations for books by other people about notable Jews Ruth Bader Ginsburg and George Gershwin are much better than their texts, and by the way, how the hell do you write a biography of Gershwin without even mentioning his Jewishness?).

Here, I’ll give you some suggestions: Judith Lieber, who survived the Nazi invasion of Hungary and fell in love with an American GI who helped liberate her from a ghetto! Think how much fun it will be to illustrate those sparkly little bags shaped like hedgehogs, cupcakes, cat-eye glasses, and hot air balloons! Or Diane von Furstenberg, whose mother was an Auschwitz survivor/member of the Belgian Resistance and whose first husband was a German prince, and who popularized the iconic wrap dress for chic working ladies that could go from the office to Studio 54! (OK, so von Furstenberg is a somewhat troubling figure, but not, like, Nazi-level troubling. You could deal with her peccadilloes in the back matter. And c’mon, can’t you see this book going from somber black-and-white to riotous, groovy ’70s color?) Oh, or what about Pauline Trigère, another European designer who escaped the Holocaust? Born in 1908 in Paris, the daughter of a Russian Jewish tailor and dressmaker, she spent her childhood picking up pins from the floor of the family business (that would make a great illustration, I’m only saying), fled to the States in 1937, before Hitler and refugee quotas made that impossible, and became a star. She pioneered the use of daytime fabrics in eveningwear and made those turtle-shaped pins that were on every Jewish great-grandma’s lapel. And her nickname was Trigger. C’mon, that’s kidbook gold. But are we getting too Ashkenormative here? Then tell me, who could be more children’s book friendly than Syrian Jewish Isaac Mizrahi? A boy who hated yeshiva! Who drew shoes and hairstyles in the Mishna! (The afterword can say we shouldn’t do that.) Who escaped into a puppet theater he built in the garage! Who talked his family into letting him attend LaGuardia High School (aka The Fame School) and was actually in Fame! Who made crazy ballet and opera costumes and collaborated with Maira Kalman! (Wait, I just thought of the illustrator for this book.) He was one of the first fancy designers to do a collection for Target! His career has had setbacks but he has persevered, like Chanel, but without dating a Nazi. (As far as we know.)

P.S.: I would also like picture books about two specific non-Jewish designers: Willi Smith, the African American designer who pioneered “street couture,” democratized designer sportswear, created uniforms for Christo’s 600-member workforce that wrapped the Pont Neuf in hot-pink fabric in 1985, designed Mary Jane’s dress for her 1987 wedding to Spider-Man, and died of AIDS at 39, far too young. Also, please give me a picture book about Madame Grès, a goddess with silk drapery (think Dietrich and Garbo, whom she dressed) who made a whole fuck-you-to-the-Nazis collection in the colors of the French flag in 1944.

And publishers, the next time you are planning a seasonal catalogue and it includes a picture book about Coco Chanel, look in the mirror and take one thing off.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.