Ghetto Marks

Eighty years ago, the Nazis established a bank in the Lodz ghetto—and created a special currency that could only be used there

After invading Poland in September 1939, the Nazis established a ghetto in Lodz in February 1940, cramming 160,000 Polish Jews behind barbed wire fencing. Occupants were forced to labor in factories, producing uniforms, boots, and other items for use by the German army. Overcrowding and lack of food led to disease and starvation: The ghetto, a mere 1.6 square miles, had neither running water nor sewer systems.

But it did have its own money—and its own bank.

In June 1940, a specialized Lodz ghetto currency was established, in denominations ranging from 50 pfennigs to 100 marks. The designs featured a background of interlinked Stars of David with a menorah on the reverse. Some of the denominations were also outlined by Stars of David separated by barbed wire. All the bills bore the signature of Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the controversial head of the ghetto’s Jewish Council, and were referred to as rumkis by ghetto residents. Along with the bills, coins pressed out of aluminum or highly volatile magnesium were issued in denominations of 10 pfennigs, and 5, 10, and 20 marks. Isaiah Trunk notes in Lodz Ghetto: A History: “The introduction of specious currency was also an effective device in the plunder of Jewish property. Jews were forced to sell their property … for ghetto scrip, for only with it could they buy only the smallest quantities of food.”

The same month as the currency was issued, a bank opened in the Lodz ghetto. Residents were required to exchange any of their remaining jewelry, foreign coins, furs, or other valuables for the official ghetto notes. (The Nazis had already frozen Jewish bank accounts and appropriated Jewish businesses and factories prior to establishing the ghetto.) The issuing bank then handed the residents’ valuables over to the Nazis to pay for the community’s meager provisions. Further pressure was exerted on ghetto occupants in September 1940 when Nazis intentionally limited the supply of food to pry more valuables out of the residents, writes Helene J. Sinnreich in her study “The Supply and Distribution of Food to the Lodz Ghetto.” The only option for “buying” food were the rumkis. Unlike in other ghettos, covertly trading food with Polish locals or buying black-market food or weapons was not an option for the Lodz prisoners: The ghetto was surrounded by ethnic Germans and anyone seen near the barbed wire was shot.

Shortly thereafter, ghetto occupants started collecting a food allowance—adults received 9 marks and children under 14 received 7 marks per month. However, many foods were simply unavailable or provided in such limited quantities that endless food lines and rioting ensued. To settle the starving residents, laborers began to receive “wages.” Eventually, laborers received some meals at work with the requirement that they were eaten on site, ensuring that families were unable to share provisions. By 1944, ghetto occupants received a single bowl of soup a day and children ages 9 and up were required to labor in the factories.

The rumkis that bought little in the ghetto were completely useless outside of the barbed wire enclosure. Yet ghetto occupants carried the bills, a fact made strikingly clear in 1942 when it was reported by some of the Jewish laborers that rumkis had fallen out of billfolds in nearby warehouses where they sorted old clothes. “The obvious conclusion is that some of the clothing belongs to people deported from this ghetto,” recorded Rumkowski in May 1942.

Indeed, deportations from the ghetto began in 1942 when occupants were ordered to prepare the sick, elderly, and young children for deportation, leaving only those able to provide labor in the ghetto. Little by little, other residents were deported to the Chelmno extermination camp, although it is clear from occupant diaries that the Gestapo intentionally misrepresented the fate of deportees, suggesting they were moved to agricultural settlements. By 1944, those remaining in the ghetto, including Rumkowski himself, were transported to the killing centers at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

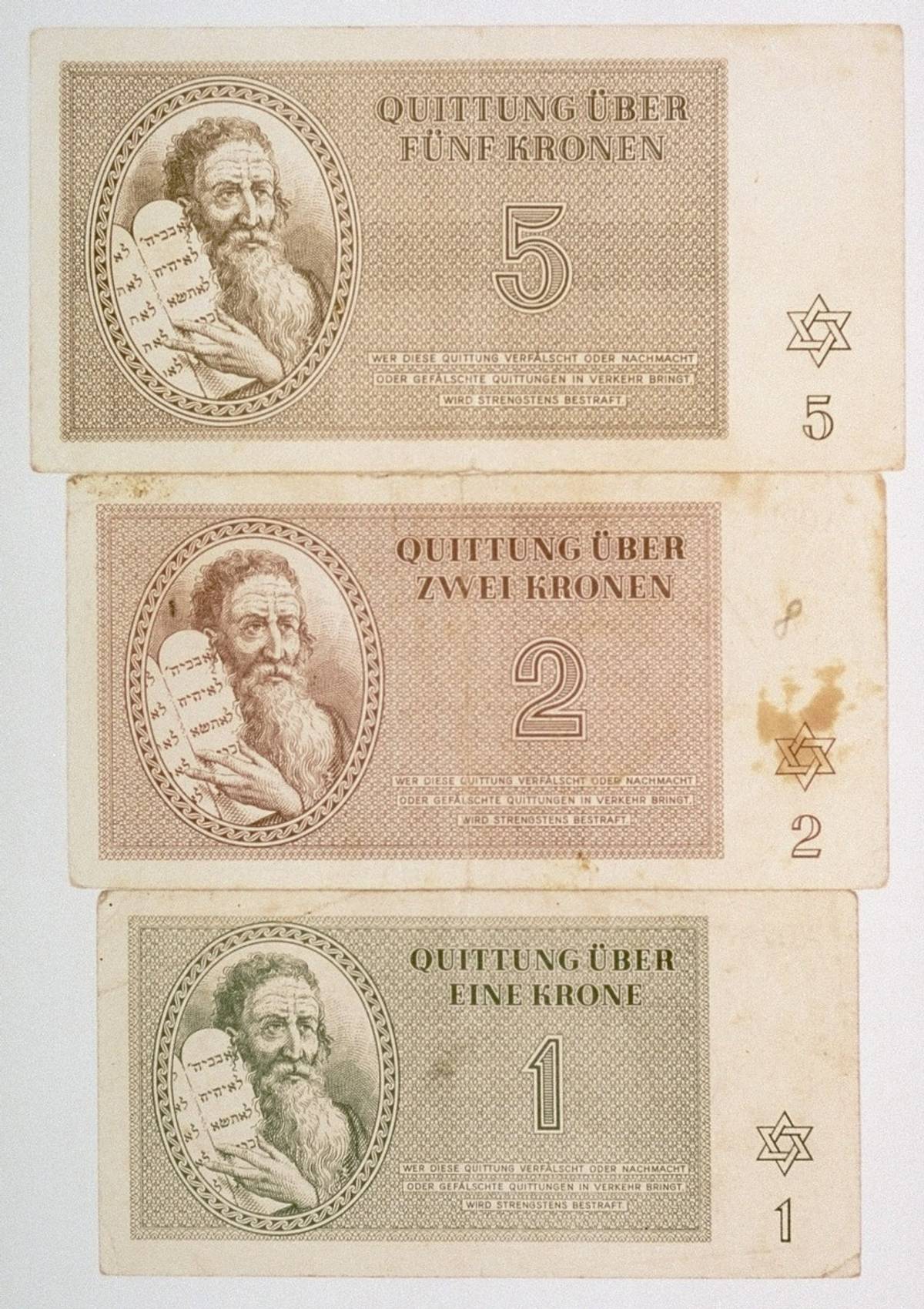

Lodz was not the only ghetto with an alternative currency. In Theresienstadt, the “model” camp prepared for inspection by the Red Cross, currency was produced in denominations of kronen. The camp kronen were used by prisoners to “repurchase their own confiscated goods” at inflated prices, and to pay a required parcel tax and a monthly “leisure tax,” according to Jed Stevenson in Numismatics: Scrip from a concentration camp is a grim reminder of World War II. The Theresienstadt notes pictured Moses holding the Ten Commandments, written in Hebrew. According to an article by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, “The notes were designed by a Theresienstadt inmate named Peter Kien … Nazi officials forced Kien to alter his original design to make Moses look more stereotypically Jewish and, ironically, to make his hands cover the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill.’” Kien was 22 at the time, a prolific artist, poet, and playwright who was murdered in Auschwitz with his family in 1944 after their deportation from Theresienstadt.

Meanwhile, in the Warsaw ghetto, established in November 1940, Nazi occupation currency also developed, but unlike at Lodz 80 miles away, smuggling and exchange with the outside world were pervasive. Smuggling was primarily carried out by small children who could exit and enter the ghetto through holes in the walls. “The best smugglers and operations soon became the new elite of the ghetto,” notes Susan J. Berger in her study A Clandestine Curriculum of Resistance. Furthermore, a so-called “gray economy” emerged within the ghetto in which raw goods were smuggled in and transformed by ghetto residents into items purchased by Polish consumers, writes Samuel Kassow in Who Will Write Our History? It is clear now that weapons were among some of the contraband. In 1943, a group of residents took up arms to resist forced deportations to killing centers. Eventually, the surviving Warsaw ghetto prisoners were sent to their deaths, primarily at the Treblinka extermination camp.

Scrip was also distributed at some concentration camps, including Dachau, Ravensbrook, and Auschwitz.

Strikingly, ghetto currencies that were not burned or melted for fuel remain intact in collections, like those at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, which holds over 1,500 pieces visible online. Kyra Schuster, curator for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum National Institute for Holocaust Documentation, told me: “I think people are surprised to see that this currency existed, just as many people are surprised to hear that there was a postal system within the camps. I believe that the reason why so much of this currency has survived is because it was small and easy to save, and in many cases at liberation, it was one of the only tangible items a survivor had that documented their experiences. We also have pieces that were found by American soldiers in the camps after liberation, or that were given to survivors and veterans after the war.”

Today, some white nationalists and neo-Nazis present the currency as evidence that Jews were paid fairly for their work, going so far as to argue that Jews had unique buying privileges including access to “special luxuries” due to the limited distribution of the currencies.

Despite such delusional arguments, viewing the notes a mere 80 years after they first appeared illustrates the extraordinary lengths to which the Nazis went to defraud and dehumanize their victims and to deceive the world about their activities. Schuster added, “In reality, this currency had little to no value. I think that it shows the lengths that the Nazis went to in order to maintain control and oppress the individuals imprisoned in the camps and ghettos even further. The printing of currency added to the illusion of normalcy and was part of the Nazi propaganda machine.”

The remaining currency has been described as “standing in silent witness” to these atrocities and to the memory of those who endured them.

Naomi Sandweiss is the author of Jewish Albuquerque, and a past president of the New Mexico Jewish Historical Society.