What happens when you combine cultural distrust of the medical establishment and structural alienation from an expensive and often hostile health care system? Along the Rio Grande border between Mexico and the United States, what you get is a thriving parallel system of health care, where folk healers called curanderos do a brisk business. Hidalgo County, Texas, has a majority Hispanic population and, as The New York Times reported at the end of 2023, “one of the highest rates in the nation of people without health insurance,” where people use curanderos “for lack of other affordable options.”

Curanderos are mainstream in the area, advertising their services through television spots and street signs. The Times piece focuses on the more benign aspects of curanderismo, such as spiritual cleansing, blessings, and divination. But not all kinds of curanderismo are so harmless. “Many Latino children have fallen ill and even died,” the story explains, “after consuming such remedies known as albayalde, azarcon, and rueda, powders often used for stomach-related illnesses that have been found to contain lead.” The “medical establishment” has issued warnings “not to rely on folk remedies for physical ailments,” but it seems dubious that people who are already so alienated from mainstream medicine will heed its scolding.

Not so long ago, Yiddish-speaking Jews had their own culture of folk healers and folk remedies, along with many of the same challenges facing residents of those border communities along the Rio Grande. Though Yiddish folk healing comprised a diverse array of practices and players, in the popular Yiddish press they were often lumped together as “babske refues”—grandma remedies. And once Eastern European Jews began migrating en masse to urban centers, the Yiddish newspapers began running sensational and often gruesome stories about babske refues gone wrong.

Before we can even talk about babske refues, however, first we have to grapple with how differently our (great-)great-grandparents viewed health and disease. Before germ theory was widely understood and accepted, Jews in Eastern Europe might have drawn on numerous, overlapping theories of disease. These could include, but were not limited to: miasma theory (“bad air” as a vector for disease); astrology (being born under an unlucky planet or at an inauspicious hour); ancient humoral theory (bloodletting was still common); disease as divine punishment for moral defect or sin, especially sexual transgression; and, perhaps most importantly, demons and the evil eye. In the face of such a dizzying array of dangers, folk healing naturally drew on a variety of strategies.

Where were the doctors in all this? Keep in mind that we’re talking about a time period, up to the first decades of the 20th century, when modern biomedicine was still in its early stages, not to mention tragically inadequate to the problems of the day, like cholera. But just like the residents of the 21st-century Rio Grande borderlands, Eastern European Jews also experienced material barriers to care, as well as ingrained distrust of the medical establishment. For many people, going to a doctor betrayed a scandalous lack of faith in God. It’s hard to imagine now, but Jews viewed doctors with intense skepticism. Even worse was a Jewish doctor, someone who advertised their heresy and alienation from Jewish life. In Yiddish, these attitudes manifested in folk sayings such as: a doktor un a kvores-man zaynen shutfem—the doctor and the gravedigger are partners.

Pentacle amulet, undatedYIVO Institute for Jewish Research/The Center for Jewish History

Traditionally, babske refues referred to the kind of healing practices centered around the home, often administered by a mother or grandmother. If you had a broken leg, you might see a feldsher, a healer who usually had some kind of military surgical training. If you had a headache or fever or had a bad fright, you might turn to a babske refue. Think of it like a first-aid kit or medicine cabinet accessible to almost anyone. Inside you’d have various kinds of remedies, including: teas and coffees, spirits, botanical products like roots and herbs, soups, fruit preserves, magic amulets, cups for cupping (bankes), enemas, soaps and clay, and baths. When Barbra Streisand’s mother made her gogl-mogl to improve her voice, that, too, was a babske refue.

This is only a fraction of the possibilities for this type of “folk healing.” There was no manual of babske refues, but rather an accumulation of folk healing practices, passed down over generations. In Fradel Shtok’s short story “The First Train,” the young protagonist, Nessi, grows pale and withdrawn as she loses hope of escaping her parents’ home. If Nessi’s family had been living in Vienna, instead of a distant province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, they might have taken her to a psychoanalyst. Perhaps a century later, they would have taken her to a psychiatrist for an antidepressant. But they are in late 19th-century western Ukraine. A Jewish mother, concerned for her daughter’s health, turns to the remedies she already knows. She makes Nessi chocolate custard and serves her viburnum (kaline, in Yiddish) tea, “to invigorate her heart.” The bark of the viburnum tree was called “cramp bark” and was supposed to be able to reduce smooth muscle tightness and alleviate period cramps.

Something as simple as a raspberry (maline, in Yiddish) could also contain soul- and body-reviving properties. In the Isaac Bashevis Singer short story “Taibele and Her Demon,” when Taibele’s (human) demon lover becomes ill, she offers him the remedy she has on hand, raspberries and milk. Milk and other dairy products were often given to pallid, weak patients. The ideal look of health was one of “blut un milkh,” blood and milk—a white face with ruddy cheeks. Milk was given to a patient in the magical belief that it would lend its robust whiteness to the patient ingesting it. Raspberries had similar magical qualities. Not to mention that its taste, especially in the form of preserves, was the kind of delight that could alleviate suffering, or at least take your mind off it for a little while.

In Zalman Shenour’s 1929 short story “Newspapers,” when Uncle Yuri starts getting the newspaper, he becomes unhappy and agitated with what he reads. Yuri is also distrustful of doctors; even just reading about them in the paper irritates him. “You hear, Feige? Here are doctors begging, we should let them cure us. Nah! And our specimen of a barber leech grumbles when he gets a guilder.” Aunt Feige knows how to soothe Uncle Yuri, however. “Aunt Feige poured Uncle Yuri a glass of excellent tea. She opened the raspberry jam to soothe his nerves. The copy that he read she put back on the commode.”

I recently taught a class on these babske refues at the Yiddish New York festival. I asked participants to share their childhood “sick day” home remedy meal or drink. To my surprise, one young woman told me that during the summer, her Odessa-born mother would buy raspberries and macerate them in sugar and put them in the back of the refrigerator. When she got sick during the winter, her mother would bring out the macerated raspberries as a special home remedy!

However, the category of babske refues took in far more than the comforting sweetness of raspberry jam. At times, these practices could be downright bizarre, as well as dangerous. If you look in the Yiddish papers of the early 20th century, you’ll find many stories in which babske refues are transplanted into new, urban contexts. In the city, some of these treatments still produced terrible results, but now there was a chance the whole world would read about them.

A 1909 article in the New York-based Yidishe Togblat had the headline “Arrested on account of a babske refue.” In that story, a father had been left to care for his sick baby. Apparently, he became distressed and confused and sought advice from “alte vayber” (old women). Unfortunately, their remedy consisted of the man holding his baby by the feet and swinging him into a glass window. Neighbors intervened before the baby landed out on the street.

How on earth could such a dreadful act be a remedy for anything? It’s hard to say exactly what was going on from such a short and sensationalized newspaper article. But remember, there was a widespread belief that disease was the result of malevolent forces (like demons) taking up residence inside the body. Treatment required driving such invaders out and was usually, at minimum, not pleasant.

In his more-than-comprehensive masterwork on Jewish folk medicine, A Frog Under the Tongue, historian Marek Tuszewicki explains that flowing from this belief, one of the methods for treating disease involved shaking, beating, or chopping an illness out. For infantile convulsions, he says that one recommended technique was to “hold the child by its feet and knock its head several times against the door frame.” It’s not hard to imagine that the disturbed father in this story heard something similar, and in a moment of panic (or inebriation or sleeplessness?) he acted on what he believed to be trustworthy advice. I found numerous such stories in the Yiddish newspaper archives. A 1929 story in the Khelmer Folksblat has the headline “Karbones fun babske refues un eytses” (victims of babske refues and advice). In that story, one of the “victims” is a woman who believed she had a bedbug in her ear. On her neighbor’s advice, she tried a “heymish” refue, which consisted of pouring naptha in her ear. It killed the bedbug, but it killed her, too.

By that point, the American medical establishment had been actively working for decades to discredit folk healers of all kinds and, where possible, to legislate them out of business. The 1910 Flexner Report had resulted in wide-ranging reforms to medical education and standards in the profession (as well as a long-lasting legacy of structural racism). In that context of reform and reaction on the part of mainstream biomedicine, it’s interesting to find a 1919 piece in New York’s Di Idishe Gazetn newspaper that makes a scientific case for the much maligned “grandma remedy.”

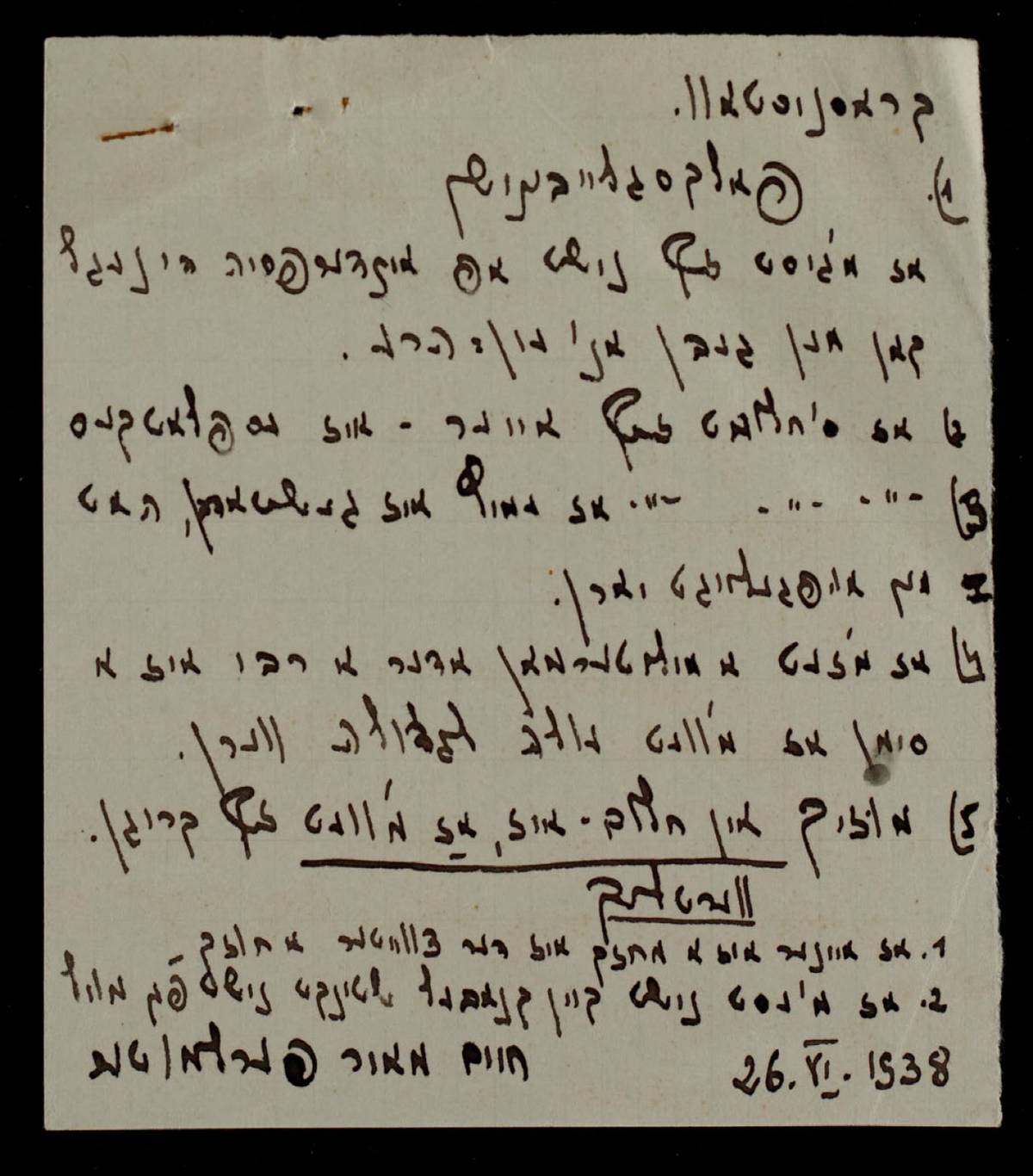

Folk beliefs from Krasnatov, Ukraine, circa 1938, transcribed by an ethnographer, including superstitions like, ‘If you see a military officer or a rebbe, it is a sign that you will (“ole le-gedole vern”) grow greater in stature’ YIVO Institute for Jewish Research/The Center for Jewish History

The piece is headlined “Babske Segules” (a segule is a magical charm or remedy) and the writer relates at length what an unnamed doctor has shared with him. The problem today isn’t that people are clinging to the old ways, the doctor says, but that they put too much trust in “medicine”! Even when he tells his patients that the best remedy would be an hour of fresh air each day, they demand medicine, not air. Not only medicine, but it must burn and have a bitter taste. Should he dare prescribe something sweet or inoffensive, they become angry, questioning his qualifications. Some of his patients, he says, are healed merely at the act of his writing out a prescription.

He goes on to discuss the old beliefs, how disease was caused by an invading force, like a demon. It makes sense to him that many babske refues consisted of bitter herbs that could drive out these evil spirits with their sharpness. He points out that today, we talk about disease in ways that are very similar. That we are “attacked” by pneumonia, or overcome by illness. When one becomes well, we personify the illness, saying that it was “battled.” There was a wisdom to the old ideas, which have not gone away, but only been transformed.

And the various teas, syrups, and bitter waters that became babske refues? This doctor argues that perhaps there is an intelligence inside man which guided him to the correct herbs and grasses, some of which are now being used by modern medicine.

But most of all, this doctor anticipates the insights of what we now call placebo therapy. He describes how he has seen many instances where belief in a medicine mattered more than the medicine itself. If the patient is convinced it will work, it will work. It’s the same as with the babske refues. A patient, he says, might gulp down raspberries in hot tea (a common belief held that raspberries could cause perspiration and thus draw out a fever), bury himself in blankets, and wake up healed of his illness. Even if the babske refue had, in truth, no connection with the healing, so what?

Now, I’m not saying that I’m abandoning our cutting edge, modern health care system just because it is outrageously expensive, puts profit over people, and endangers patients with endemic misogyny, racism, fatphobia, and other assorted sins. (Though I would really, really like to.) But I found myself moved by this anonymous (possibly fictional?) doctor’s words from a century ago. It’s true, we can’t cure cancer by staying positive, and it’s cruel to suggest otherwise. But it’s never a bad thing to be reminded how much power we do carry within ourselves. And a simple jar of raspberry preserves has brought a surprising amount of joy to my gloomy winter breakfasts.

MORE ABOUT ASHKENAZI MAGIC: Jewish magic is having a zeitgeist moment. My friend (and inspiration!) Sam Balinsky-Glauber will be teaching a 10-session course for YIVO this spring called “Psychics and the Occult in Modern Jewish Culture.” Sam is a phenomenal researcher and scholar and he’s been doing really groundbreaking work in this area. His class will be capped at 15 students, so if this sounds interesting, I recommend you register ASAP. More information here …

ALSO: Workers Circle will offer “Winter in Yiddishland Online,” an all-day virtual program with Yiddish classes, music, lectures, and more. Feb. 4, 10 a.m.-6:30 p.m. Register here … Women on the Yiddish Stage has been a highly anticipated 2024 release in my household. This new volume contains “an array of scholarly essays that challenge the existing historical accounting of the modern Yiddish theater; highlight pioneering artists, creators, and impresarios; and map sources and methodologies of this rich area of forgotten history.” Come to the book launch on Feb. 5, when co-editors Alyssa Quint and Miryem-Khaye Seigel will be joined by moderator Elissa Bemporad. Register here … The Farbindungen Yiddish Studies Conference will take place over Feb. 18-19. The theme this year is “Shtumer alef: Beginnings, Silences, Partnerships.” Judging by last year’s conference, the proceedings will no doubt be terrific and a great opportunity to connect with young scholars and activists. More information here … Applications for the Steiner Summer Yiddish Program at the Yiddish Book Center are due by Feb. 5. It’s a seven-week program for undergraduate and graduate students as well as recent graduates. Participants can earn college credit for the summer while also having the time of their lives. More information here … On Feb. 7, University College London presents “A Piquant Curiosity: A Yiddish Actor and the Gender-Bending Play Yes a Man, and Not a Man,” a lecture by Zachary Baker. Register here.