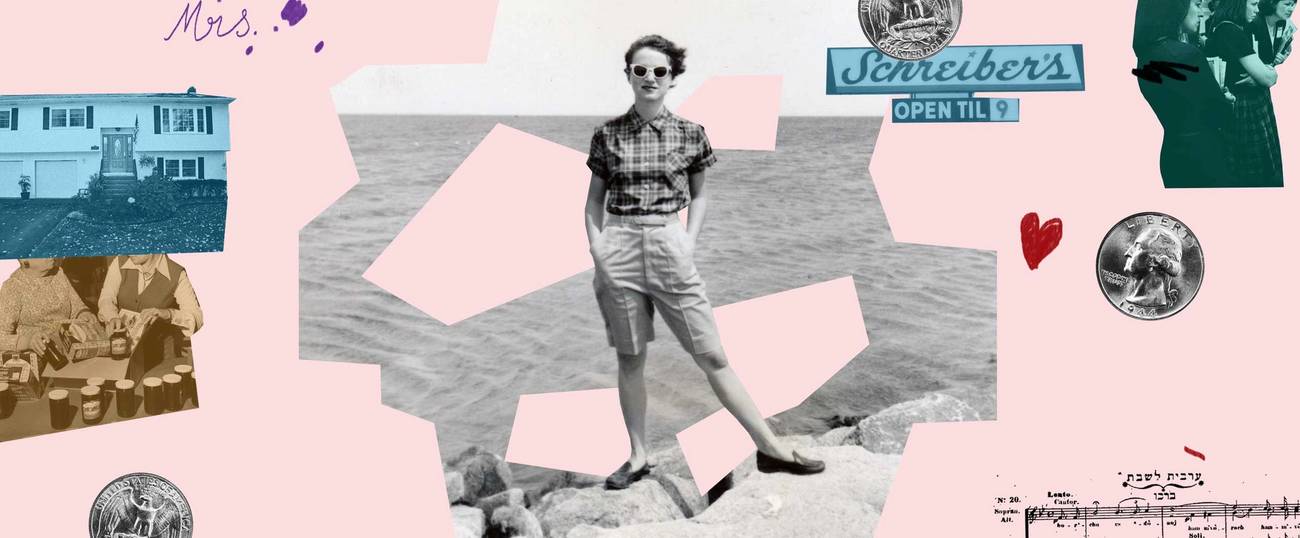

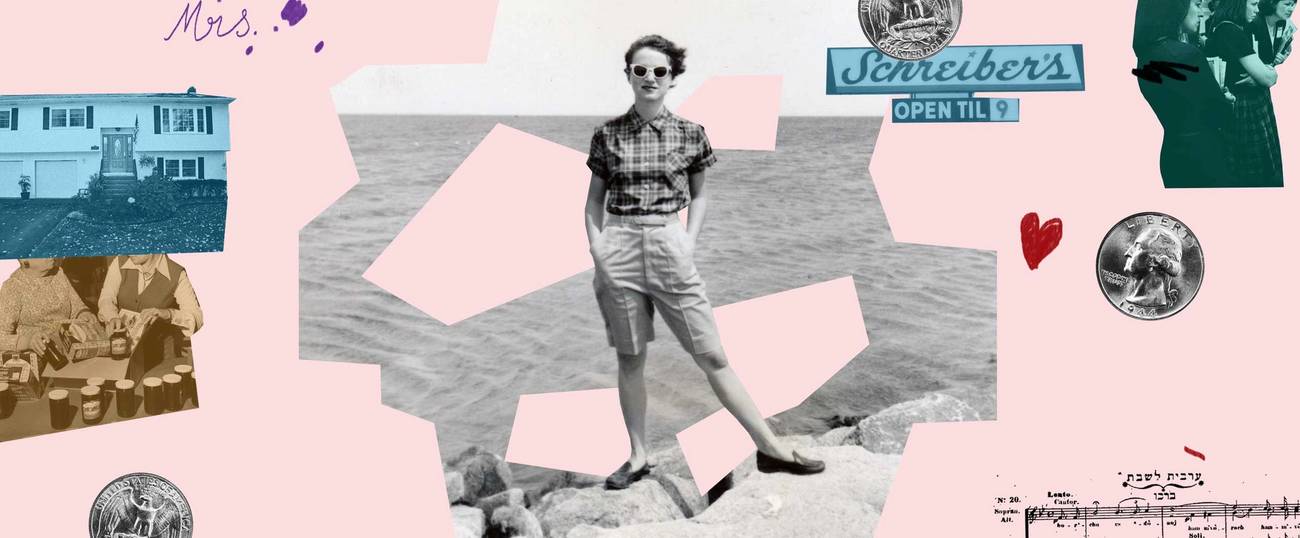

Growing Older—With an Emphasis on ‘Growing’

At home and at work, baby-boomer Jewish women are redefining what it means to be a grandmother

Although they are part of the baby-boom generation by virtue of their age, women raised in traditional Jewish homes from the late 1950s through the early 1970s stand apart from their demographic peers.

Many of these women, who now range in age from their late 50s to about 70 years old, were raised by immigrants or first-generation Americans. Their home and communities—often suburban—were infused with traditional Jewish values, especially regarding the role of women. Their mothers didn’t have careers, and their major role in religious life centered on volunteering: This was the era of the synagogue sisterhood, Hebrew-school bake sales, and Hadassah meetings. Their communities did not approve of, or even acknowledge, the burgeoning feminist movement of the era. “Old world” values, where family and traditional roles took precedence over everything else, remained paramount.

Unlike stereotypical baby boomers, these women were not raised with the sense that they could be anything they wanted to be. Many went to college—often the first generation in their families to do so—but the emphasis was more on education than career. These women were not pushed to be professionals, but rather to marry them. They often acquiesced, but they also saw a changing world around them. And once they had children of their own, they often tried to change the scripts they had grown up with—particularly for women. They might have been raised to marry doctors but they pushed their own daughters to be doctors.

After redefining what it meant to be a Jewish mother, these women are now redefining what it means to be a Jewish grandmother. As this generation of Jewish women are facing empty nests, retiring spouses, and grandchildren, they are reinventing themselves in ways that their own grandmothers could never have imagined: While previous generations of Jewish women spent much of their time babysitting for the grandkids on a regular basis, many baby boomers are instead returning to school, getting jobs, traveling—and sometimes, getting divorced. Many of them, who were dedicated, full-time mothers, deeply want a good relationship with their grandchildren but don’t necessarily want to be as involved as their grandparents once were. They see this phase of their lives as an opportunity to become part of the world they pushed their kids into, a world they couldn’t truly join until now.

*

When I asked my older sister, who is now 60, her impressions of growing up in the 1960s and ’70s in our traditional Jewish suburban enclave in the New York metropolitan area, all she could remember was going to the mall to buy a suede fringed vest. Her contact with anyone from the “outside world” was limited to the guy who sold us fruit: He had a ponytail and our mother made sure to explain to us, in a whisper the first time we met him, that he was a hippie. We were four daughters but our careers were never a real concern. Feminism or the women’s liberation movement was never discussed, except as a joke.

Many Jewish boomer women, like my sister, were raised in a world that was changing around them, while their own communities stubbornly clung to the world as it was. These were specifically traditional Jewish suburban communities, like the one my sisters and I grew up in. While their secular sisters were venturing out into the world of feminism, sexual freedom, and drugs, women from these communities were watching from the sidelines. They might have ridden out the turbulent ’60s and ’70s from suburban perches, but they still took notice, even as they went to college, got married, and raised families.

I spoke to dozens of Jewish women who grew up in this milieu. (I’ve changed their names to protect their privacy.) Most of them either left their careers to raise their kids or never really got started in the working world. While other boomer women were blazing trails in the workforce, these women focused on raising their children.

Jaimie, 62, was raised in a small town in Connecticut in a modern Orthodox community. She married in her 20s and divorced after more than 30 years. “I feel like my generation experienced a revolution in the world in how it was to be a woman and how it was to be a parent in a way that I don’t think previous generations had quite as stark a change,” she told me. “For me, the values I was raised with were really internalized. I went to college, I felt very liberated, but the fact is my parents sent me to college to get married. When I was growing up, I didn’t know a single woman who worked.” Jaimie sent each of her four children—two boys and two girls—to college to be educated and to become independent.

At the time, though, Jaimie’s college experience didn’t really shift her essential worldview: In the end, she said, “I married someone who wanted a wife to stay at home and I was happy to do that.”

While Jaimie raised her kids, she dabbled in making jewelry and teaching Pilates. They were both hobbies until she was divorced, on her own, and needed to support herself. “My marriage was confining,” she said. “In my generation, men were very chauvinistic. My husband used to make fun of women’s lib, and he was really negative about my teaching Pilates. I could do it as long as supper was on the table and it didn’t interfere with his schedule.”

While Jaimie wasn’t happy in her marriage she never would have had “the nerve” to get divorced if she hadn’t discovered her husband’s affair. The divorce turned out to be a liberating experience. “Once I got divorced, I could be anything and I could do anything,” she said. “It was another world.”

The divorce rate for baby boomers has tripled since 1990, with one-third of these divorces among couples married 30 years or more. The women I spoke with reported that they were unsatisfied with their marriages and, significantly, wanted the opportunity to pursue their own interests and independence for the remaining years of their lives. In addition, Jaimie suggested, a bigger issue among Jewish women of her generation is the men’s inability to change as their wives, and the world, are changing around them.

To be fair, these Jewish boomer women are changing a lot. “We saw our mothers, cook, clean, and take care of the kids,” said Jaimie. “But we also saw a different model in the world. We understood that you need a career but we also felt we should do what our mothers did.” Many of these women followed their mothers’ path but they made sure their children knew that their lives could be different. And now they are realizing their lives could be different, too. They no longer want to follow their mothers’ paths into grandmotherhood.

For Jaimie, that means redefining, for herself and for her kids, what it means to be a grandmother. “I see my grandchildren and I make an effort to make dates with them, but I certainly do not want to do it every day. Sometimes I feel guilty. Sometimes I don’t. I spent a lot of years in the role of mother. I don’t want to keep doing it. I’ve done it,” she said. “I think my kids see me as self-interested, but I can live with that. At this point in my life I put myself first.”

Jaimie echoes the sentiments of many Jewish women her age who started to think differently but essentially hewed to traditional roles within their families as young wives and mothers. Now, as they become bubbes, they are rewriting the script.

Amy, 66, has six children, numerous grandchildren, and a great-grandchild. She says she wants to find balance in her life, but it’s hard to do that because someone’s always calling her to babysit. Amy stayed home to raise her children and, she says, she did her time as a mother; she does not want to spend the rest of her life taking care of children. She and her husband have recently started traveling and her children are learning that Amy, in this next stage of life, is not on call to take care of the grandchildren—and she does not seem to feel very guilty about it either. “I started doing less,” she said. “I lived too many years like a piece of Turkish Taffy with each one pulling at me. I said, you know what? I don’t feel like it anymore.”

But Susan, 62, does. She raised her six children and she now has more than 25 grandchildren. She started out babysitting one day a week; it has since turned into a full-time job. She feels bad, she says, not giving to each child equally. She is quick to say that she adores her grandchildren but she admits that she is getting tired. “Sometimes at the end of the day, I think, wait a second, that was just too much,” she said. Still, she doesn’t plan on changing her situation anytime soon.

Shari, 70, who raised three children and is now a grandmother of 10, notes: “We were on the cusp of something different while raising our children. I think our mothers were not necessarily the role models we wanted to be as grandmothers. We have to kind of reinvent ourselves. But we have to create the model.”

Shira, 56, also stayed home to raise her kids. A mother to eight and a grandmother to two, she is looking to develop her career as an artist now that her youngest is nearly finished with high school. She admits to being frustrated in balancing her career goals with her commitment to her grandchildren. Part of the issue for Shira is that she was completely devoted to raising her children. She says she never could have focused on anything else while she was bringing them up. But now she can. “I’m just entering this new stage,” she said. “The kids are getting older, leaving the house, I can do whatever I want.”

But babysitting requests are increasing and she sees a scenario in which she will have to start saying, no, I can’t watch him that day. Will she be perceived as selfish? Shira can accept that. “I am looking for a new identity through my work,” she said, adding that she is also seeking financial independence. She is definitely stepping outside of her comfort zone—and she likes it there.

Shira is currently teaching art and selling her work online and in a gallery. She says it’s been an “empowering” experience. In that way, Shira resembles many boomer women who are discovering that pursuing dreams that they once deferred for spouses, for kids, can be incredibly satisfying.

For many of these women, making money is also more empowering than they anticipated. Shira doesn’t necessarily need the money but she says she realizes she likes contributing to the household income.

Others, like Jaimie, were pushed into the workforce out of economic necessity—which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. “It gave me the push I needed to do the thing I loved,” she said.

Whether it’s by force or design, all these women are discovering that redefining themselves as someone other than a wife, mother, or grandmother is an exciting, interesting task. In fact, for many boomer women living a traditional Jewish life, there is a sense of “it’s now or never” informing much of what drives them into this next chapter of their lives. This is their opportunity to redefine themselves—and they are going for it, often with a passion that surprises even them.

“I never had the time to pursue my art,” said Shira. “My friend said I could just stay home now but that’s not the lifestyle I want. I want to be doing something.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Naomi Grossman is a writer and CEO of LifeJourneys Media.