Is Zionism the Problem?

A new history of Matzpen and the anti-Zionist left in Israel

A few years ago, I was invited to a small private gathering of Jewish studies scholars to talk about the future of Zionism. One of the participants, a leading figure in American Jewry, was offering his views on the two-state solution. At one point I interrupted him and asked, “What if the two-state solution is no longer possible?” He sat silent for what seemed like a long time, and then replied, “If that were the case, it would be the end of my Zionism.” It was a starkly honest moment. I think few liberal Zionists would respond with such candor.

Even as two-state-ism seems to drift further and further from the shore, it seems many liberal Zionists have turned it into a kind of dogma that one day their vision will prevail, a kind of political “Ani Ma’aminism,” (“I Believe-ism”), because in their view two states is the only reasonable solution. What liberal Zionists remain committed to, regardless of their differences, is Zionism. But what if Zionism is the problem?

Today, anti-Zionism, certainly on the left, is viewed as identical to being against Israel, that is, a repudiation of the State of Israel and the Jewish right of self-determination. In some circles anti-Zionism itself is considered antisemitism. But anti-Zionism was not always opposed to the State of Israel. In fact, in some circles in Israel, anti-Zionism, or the de-Zionization of Israel, was intended to save the State of Israel.

In his excellent new book, Matzpen: A History of Israeli Dissidence, Lutz Fielder, of the Selma Stern Center for Jewish Studies Berlin-Brandenburg, offers the most comprehensive history now available in English of the anti-Zionist left in Israel. Also worth noting is Ran Greenstein’s Zionism and its Discontents published in 2014. While Fielder’s book (translated by Jake Schneider) focuses on the anti-Zionist Matzpen (Compass) movement, Fielder draws his circle wider and includes the various offshoots of the Israeli Communist Party (Maki and Rakah) and the way Matzpen rose to become a strong dissenting voice for peace in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Matzpen’s political agenda was broad, unambiguous, and comprehensive: the de-Zionization of Israel, including erasing the Law of Return, passed in April 1952, which assured the right of citizenship to any Jew in the diaspora who arrived in Israel and stated his or her intention to immigrate.

When most people think of “the left” in Israel, they think of what can be called the Zionist left: Martin Buber, Judah Magnes, Gershom Scholem, Arthur Ruppin, and founder of Hadassah Henrietta Szold, all of whom supported a binational state of Jews and Arabs (now called “one state”). Or the Shomer Hatzair Kibbutz movement, which sought a synthesis of socialism and Zionism. Today one may think of the Meretz party. But there was a whole other left in Israel, an anti-Zionist left, that has been all but erased from Zionist historiography. The major figures in these movements, most of whom few American Jews have ever heard of, include people like Akiva “Aki” Orr, Moshe Makover, Oded Pilavsky, Tikva Honig-Parnass, Moshe Sneh, Shimon Tzubari, Haim Hanegbi, Eli Lobel, and Natan Yellin-Mor. They were committed to Israel, yet believed that Zionism was preventing Israel from becoming a socialist country in the Middle East where Jews and Arabs would be treated equally. For these and other figures, Zionism as an ideology was preventing Israel from becoming an exemplary state of equality for all its citizens. For Matzpen, Israel was not the problem. Zionism was.

Matzpen was the name of the journal published by the Israeli Socialist Organization, which broke from the Israel Communist Party in 1962. (In the 1980s, it changed its name to the Revolutionary Communist League [RCL].) It is significant to note that many in the anti-Zionist left remained aligned in various ways with the communist and socialist parties in their native countries, particularly in or in the dominion of the Soviet Union. Some of the most vehement battles among Israeli communists revolved around whether to sever ties or remain bound to the party operatives in the Soviet Union after Stalin.

Many in Israel who know little about Matzpen know about one of its short-term members, Udi Adiv, of the left-wing Kibbutz Gan Shmuel. He was a commando soldier who served in a unit that entered the Old City of Jerusalem in 1967, but he was later tied to a Palestinian terrorist ring in Syria. He was arrested by Israeli forces and in 1973 was convicted of treason. Adiv was a member of Matzpen for a very short time and was part of a more radial splinter group called Haziz Aduma (Red Front) that had connections to various Palestinian terrorist organizations. Many Israelis thought Matzpen was connected to Arab terrorist movements, but as Nitza Erel shows in her 2010 Hebrew book, Matzpen: Conscience and Fantasy, that was really not the case. Some who passed through Matzpen, like Aviv, were connected to terrorists, and others had contacts with certain Arab groups with whom it was illegal to have contact at the time. We must remember that Matzpen was the premier radical leftist anti-nationalist organization in Israel in the late 1960s and early 1970s and thus was a magnet for radical types, some of whom moved on to more destructive behavior.

Matzpen, the name this new movement picked for its organ, soon became the name of the movement itself, never large in number, but especially after 1967 a code word for radical dissent in Israel. In many ways, Matzpen’s founding in 1962 was auspicious. The Port Huron Statement, founding document of the New Left in America, was written in 1962, and the French war in Algeria ended in 1962. That war was a watershed for the global anti-colonialist left, specifically in Europe. Matzpen served in part as the arm of the New Left in Israel, openly opposing the state of Israel’s support of the colonialist French in Algeria. Matzpen supported the FLN and Algerian dissidents against the French occupiers. Eli Lobel, later of Matzpen and then living in France, connected Amos Kenan and Uri Avnery, both one-time members of the Lehi, the right-wing Israeli underground, to FLN leader Henri Curiel. In 1960 Avnery and Kenan, with others, founded the Israel Committee for a Free Algeria.

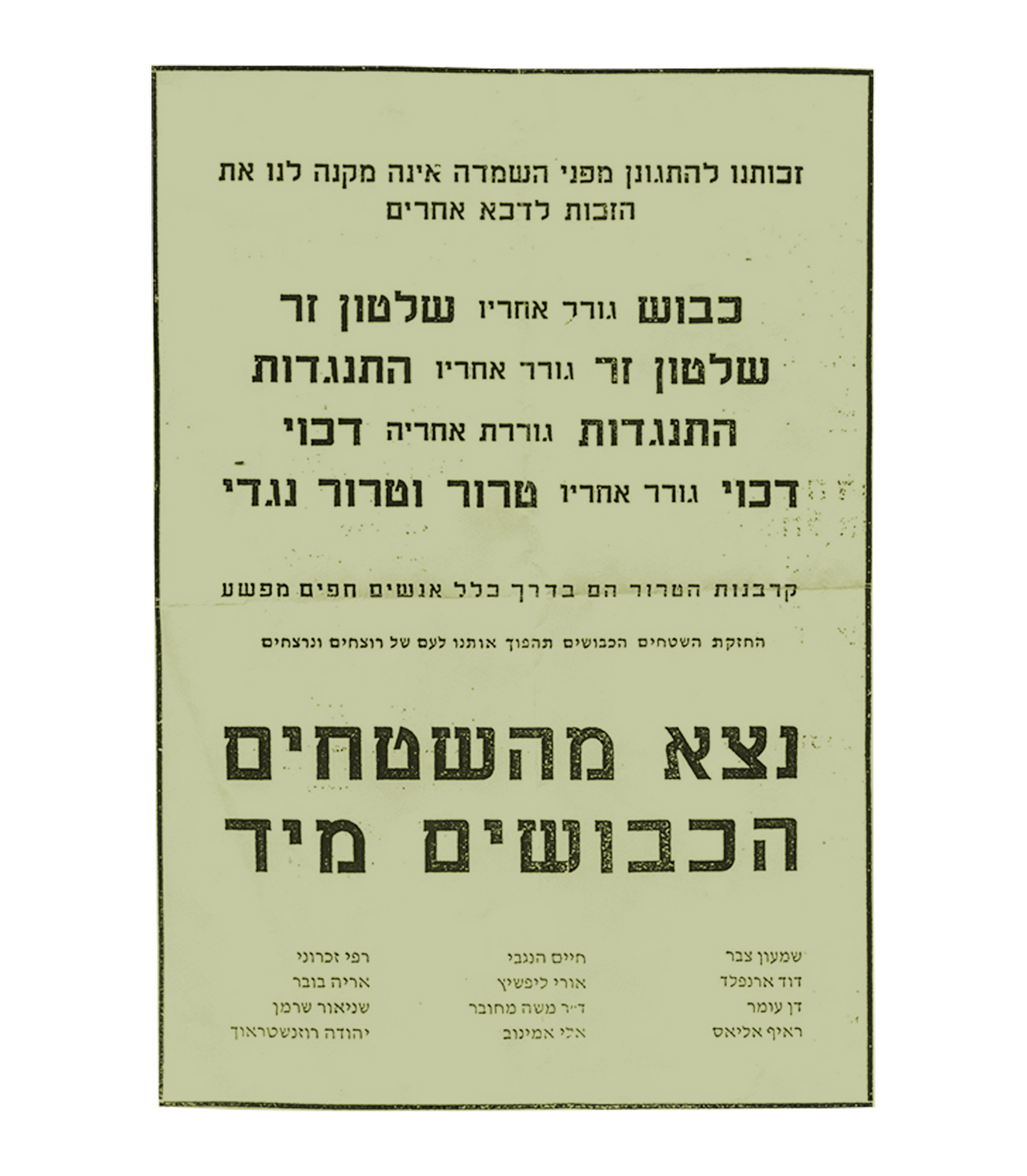

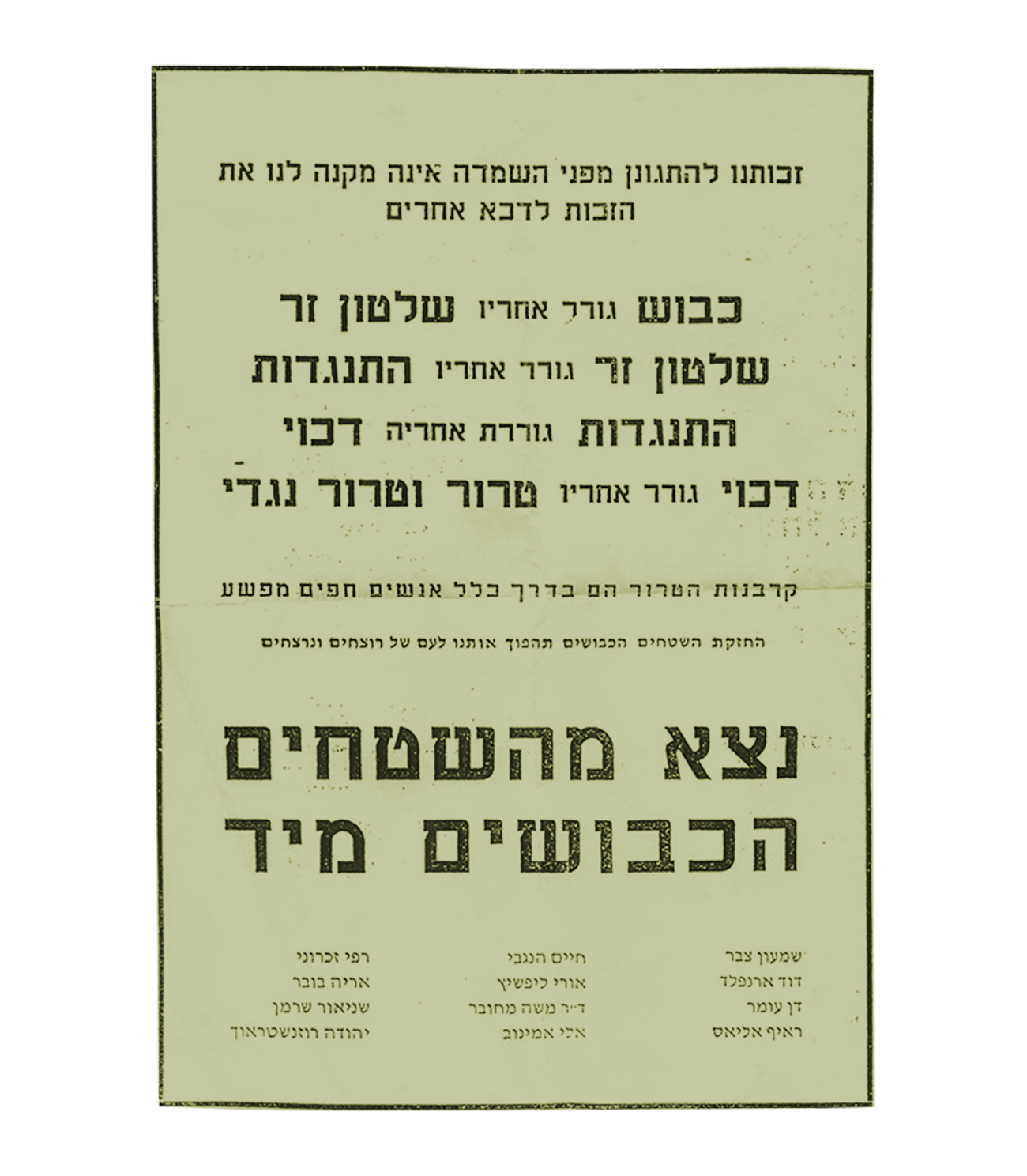

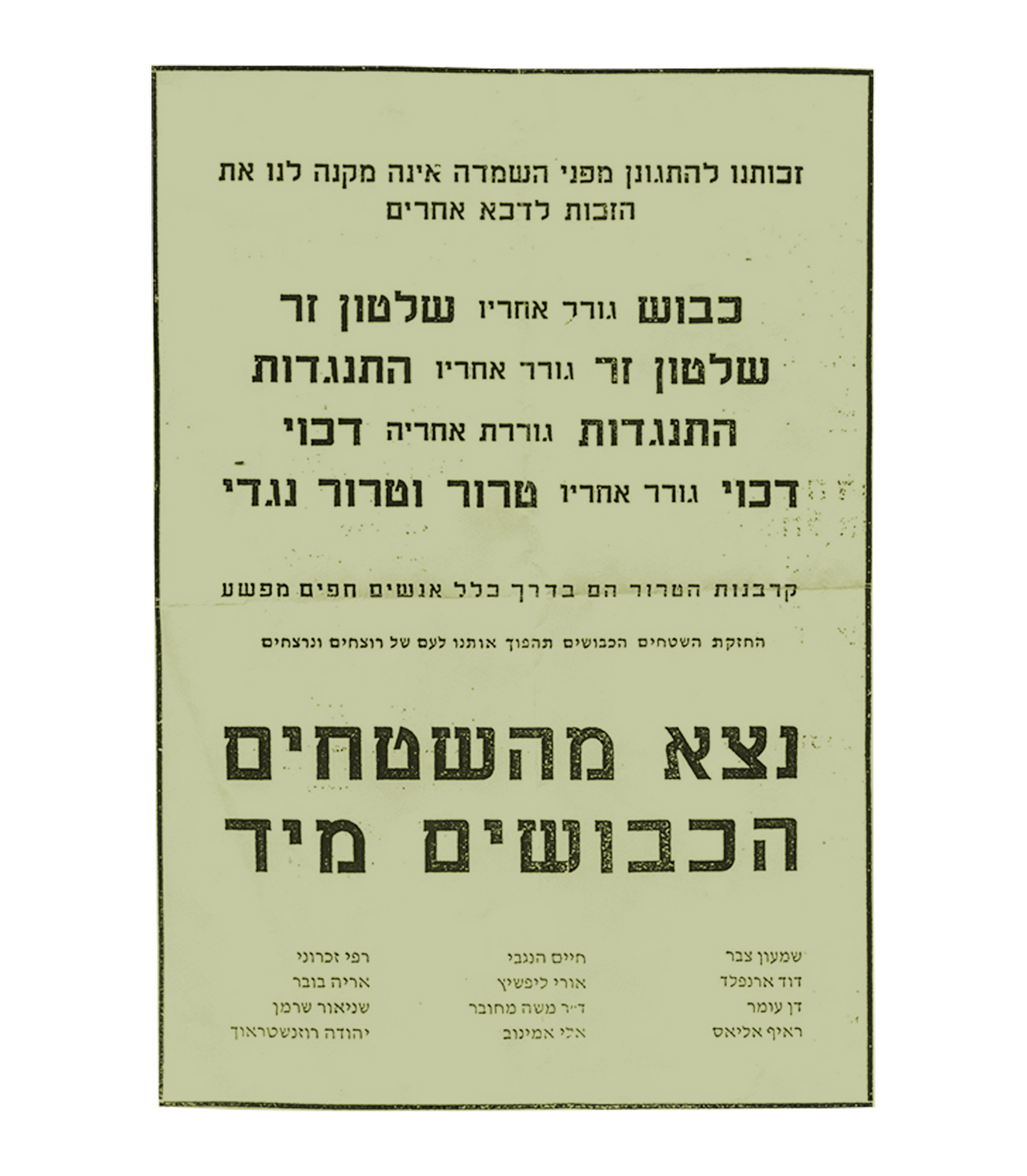

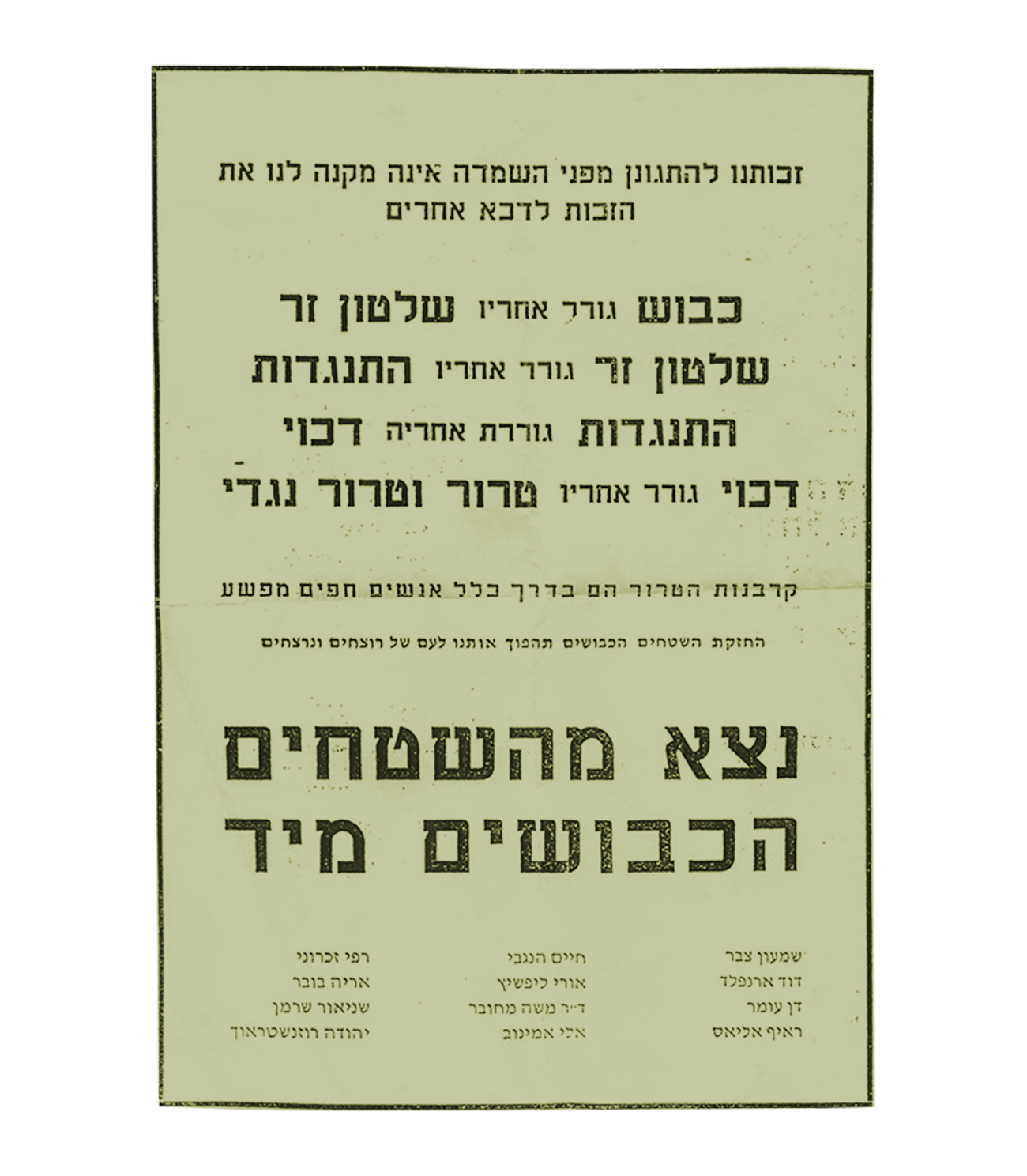

The influence of Matzpen as a movement from 1962 to 1967 was quite small, even minuscule, limited mostly to young communists, socialists, students, bohemians, and artists. The name recognition of Matzpen far outweighed its influence in Israeli society; it became a household name in Israel after 1967, because of its immediate call to withdraw from the territory won in June of that year. Most Israelis disagreed with its program. But while many Israelis were celebrating the “liberation” of the territories, and others were seemingly bewildered by the sudden expansion of Israel, Matzpen was the first organization to call for immediate withdrawal from the West Bank, Gaza, and the Golan Heights in June 1967, viewing occupation as a blatant form of settler-colonialism. A pamphlet titled “Get Out of the Territories Immediately” was published and signed by Machover, Arie Bober, and Eli Amoniv just days after the end of the war. An important figure to mention here is Tikva Honig-Parnass, who fought with the Palmach in 1948, and served as the secretary of the left-wing Mapam (Unified Workers Party), who later abandoned Zionism and joined Matzpen after 1967 because of its immediate stance against the occupation. She subsequently served as a leading figure in the movement.

Matzpen’s political agenda was broad, unambiguous, and comprehensive: the de-Zionization of Israel, including erasing the Law of Return, passed in April 1952, which assured the right of citizenship to any Jew in the diaspora who arrived in Israel and stated his or her intention to immigrate. As Moshe Machover wrote, “each request to immigrate into Israel should be decided separately on its own merits, without any discrimination of a racial of religious nature.” In short, like some left-wing Zionists such as Martin Buber, Matzpen was opposed to the very notion of a “Jewish” state that would by design privilege Jews over others in the land. While Martin Buber believed Zionism could avoid the pitfalls of chauvinism and adhere to humanist principles (what he called Hebrew Humanism), Matzpen held that Zionism could not be severed from its chauvinistic roots. Buber’s progressive vision of Judaism could never be sustained in light of Zionism’s nationalist agenda, which could never produce a truly equal society. As Akiva Orr stated, in Matzpen there were two unassailable principles: anti-Zionism and anti-capitalism. For Matzpen, the problem with true equality in Israel was not one’s interpretation of Zionism, but Zionism itself.

In his book, Fielder digs deep into the Matzpen archives (now available at Matzpen.org) among others, exposing internal rifts and some fascinating alliances. For example, some in Matzpen were opposed to Arafat and the PLO because they felt Arafat was a nationalist and Palestinian nationalism was no better than Jewish nationalism. Much of the anti-Zionist left was anti-nationalist. Derekh Ha-Nizoz (The Path of the Spark), a group that was part of Matzpen and then split, was more sympathetic to the left-wing Marxist PDFLP (Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine) which split from George Habash’s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in 1969. Derekh Ha-Nizoz members met with PDFLP secretary Nayef Hawatmeh in London in 1982. Hawatmeh was the one who reached out and was interested in a dialogue with anti-Zionist Israeli leftists who shared a common dream of a socialist revolution in the Middle East. Matzpen also sympathized with the Arab Israeli ‘Al Ard group, even publishing a Hebrew version of ‘Al-Ard’s report in the Matzpen journal in 1964.

‘Al Ard was formed in the 1950s by Arabs living in Israel and fighting for equal rights. It was outlawed by the Israeli government in 1964. By today’s standards it would hardly be radical. This speaks to the way Matzpen, or at least some of its members, viewed themselves as part of a larger Third Worldism, sparked by the Trotskyist Fourth International in 1938, calling for a permanent worker’s revolution. Many Matzpen members were influenced by New Leftists in France and Germany, some even immigrating to Paris and London, where they continued their work for Matzpen and the de-Zionization of Israel.

Another fascinating aspect of the anti-Zionist left in Israel is how many of its members began on the far right, for example in the Israeli underground Lehi, and moved to the far left in the 1960s. In Café Ta’amon in Jerusalem, Matzpen members, Israeli Black Panthers, who formed in the Musrara neighborhood in Jerusalem, far-left Zionists like Uri Avnery, Hebrew writers and artists, and far-right Canaanites mingled and discussed politics, art, and literature. In some way the far-right/far-left symbiosis is not so far-fetched. Lehi fought to end the British mandate in order to secure Jewish sovereignty in the land; Jewish socialists and communists fought to end the British mandate to end Western imperialism. Right-wing figures such as Amos Kenan and even poet Natan Alterman had ties with some Matzpen revolutionaries. The Semitic Action Group (Pe’ulat Ha-Shemit), a far-left group including many who came from the far right—including journalist Uri Avnery and Natan Yellin-Mor, who became one of the leaders of Lehi after its leader, Avraham Stern, was killed by the British in 1942—published a Hebrew Manifesto in 1958, cutting ties with the right and joining the radical left, and advocating severing ties with the Jewish diaspora and founding a new Hebrew Nation. Avnery continued to identify as a Zionist, albeit a “heretical” one.

Many of the things Matzpen advocated in the 1960s and 1970s have become acceptable positions: negotiating with the Palestinians, protesting against the occupation, fighting for Arab equality, and demanding that Israel address abject poverty and curb the free market, including the impact of globalization on Israeli society.

Another facet of this right-left symbiosis was the close ties with the Canaanites, led by poet Yonatan Ratosh, whose program to sever Israel from Judaism and the diaspora, and even from Jewish peoplehood, resulted is some far-right positions. Like Matzpen and the anti-Zionist left, the Canaanites, also known as the Young Hebrews, were also anti-Zionist, albeit in a very different way. They adopted the basic tenets of Zionism to an extreme that swerved into anti-Zionism. For example, the revival of Hebrew and the “negation of the diaspora” were cornerstones of Zionist ideology. Ratosh and the Canaanites made those the foundation of a new ideology of radical autochthony, arguing that only those who live in the land and speak Hebrew can be part of a new Hebrew Nation. Inhabitants of the land were Hebrews, not Jews. “Jews” were a product of the diaspora; Judaism was a product of the diaspora; Zionism was an invention of the diaspora. Canaanites sought to reinvent pre-Israelite roots in the land, giving their children names like the biblical warrior Nimrod, after the king of Shinar, and the names of Canaanite gods and goddesses.

In his famous “Opening Speech,” delivered in 1944, Ratosh, who began as a Revisionist Zionist follower of Jabotinsky, said, “Whoever comes from the Jewish Diaspora … is a Jew and not a Hebrew, and can be nothing but a Jew … Whoever is a Hebrew cannot be a Jew, and whoever is a Jew cannot be a Hebrew.” Ironically, Ratosh was born in Poland and began to develop his Hebrew Nation ideas while living in Paris. Arabs who lived in the land could become a part of this new Hebrew Nation by abandoning Islam and Christianity and joining in rebuilding an ancient, autochthonous society. The land and the language determined the nation. Nothing more.

What the right and left share here is that, at least in regard to the Canaanites and Matzpen, both sides were opposed to Israel being a “Jewish” state and supported transnational movements; Ratosh preferred a Hebrew, or Semitic, Nation, and Matzpen a socialist state. In a sense, the rightist Canaanites and leftist members of Matzpen shared the view that Zionism was the problem, for different reasons and toward different ends.

Lest liberal Zionists think that today’s version of Religious Zionism, founded by Zvi Yehuda Kook, is the problem, let us remember that it was the secular David Ben-Gurion who declared that “the Bible is our only mandate,” and that the Jews have the “eternal” and “historic” right to the land, echoing what Chaim Gans called in his book A Just Zionism, “proprietary Zionism.” And it was moderate secular Zionist Chaim Weizmann who said, “This land is not only the land of rescue [hazala] but the land of redemption [geula].” While Religious Zionism may view Zionism through the lens of tradition, something we find already in Abraham Isaac Kook, secular Zionists view national revival as inextricably tied in some way to religion, albeit not as tightly as do settler Zionists. Ben-Gurion believed the Arabs would eventually come around; he could not acknowledge the right of Palestinian nationalism, only Jewish nationalism. Matzpen, here aligned with Jabotinsky, disagreed. Ben-Gurion believed the land belonged to the Jews, and expected Jews would treat Arabs fairly, but never equally, certainly not as a collective. Matzpen’s view was that true equality in the land between Jew and Arab was simply impossible, not only in practice but by design, as long as Zionism remained the regnant ideology of the state.

I think they were right.

The question of Zionism as a form of colonialism has been debated for decades, and here Fielder correctly places the Algerian War at the center of the socialist left in Israel on this question. In that war, Israel supported the colonizers against the colonized. Edward Said’s The Question of Palestine made perhaps the most cogent argument about Zionist colonization. And the Tunisian-French Jewish writer Albert Memmi, in his book The Colonizer and the Colonized, made the strongest case against colonialism in relation to the Algerian War. Memmi was certainly on the left, but a Zionist, and he did not intend to extend his critique of colonialism to Israel. But others did. Meir Smorodinsky, an early member of the Israeli Socialist Organization, who was once a member of the Israeli Communist Party, noted, “Just as the Zionist era is linked to the colonialist moment, the end of Zionism is linked to the end of that movement; it ought to fear the same fate as the French settlement in Algeria, which never disavowed colonialism.” We often do not see the connection between the rise of anti-colonialist leftists in Israel and the war in Algeria, and Fielder rightly corrects that significant memory lapse.

The factionalism around Israeli leftists in the 1960s through the 1980s was part of its demise, a common fate of the left. Matzpen divided into Matzpen Tel Aviv and Matzpen Jerusalem. The Jerusalem branch, led by the fascinating Michel “Mikado” Warschawski, was committed to a Trotskyist version of Marxism, while Matzpen Tel Aviv was less ideologically pure, more bohemian and pragmatic, and began forging new ties with the Israel’s communist parties (Maki and Rakah), which retained some allegiance to the Soviet Union. In addition, they deviated from Matzpen Jerusalem’s “one-state orthodoxy.” Warschawski, born in 1949, is the son of the former chief rabbi of Strasbourg and, before 1967, came to Israel to study the Religious Zionist yeshiva Mercaz HaRav. He spent time at a yeshiva at Kibbutz Shalavim, and during the war he personally witnessed the deportation of Arabs from nearby villages. After the war, he was told no such deportations took place. He later visited the markets in Hebron; after engaging with the Arabs there, he wrote, “As if slapped in the face, I suddenly became aware that … he was the oppressed, and I was with … the one’s with power.” Through the Israeli lies about deportations and the oppression of the occupation, he was transformed, becoming a Trotskyist and, subsequently, a leading figure in Matzpen Jerusalem.

By the 1990s Matzpen as a movement was over, although small groups of young anti-Zionist Israeli communists and socialists remain. The Alternative Information Center (AIC), a joint Palestinian-Israeli nongovernmental organization, was founded in 1984 by Warschawski—who three years later was arrested, and later given a short prison sentence, for providing aid to illegal Palestinian organizations. The AIC serves as the remaining organizational arm of Matzpen’s ideology. The Zionist narrative was too strong, the trauma of the Holocaust too strong, the rise of free-market capitalism too strong, and the rise of religious nationalism too strong. A small, radical, left-wing movement like Matzpen simply could not remain afloat. And yet, many of the things Matzpen advocated in the 1960s and 1970s have become acceptable positions: negotiating with the Palestinians, protesting against the occupation, fighting for Arab equality, and demanding that Israel address abject poverty and curb the free market, including the impact of globalization on Israeli society.

But there is more, especially as this may relate to the diaspora context. Let me return to my initial anecdote about the crisis of liberal Zionism. Matzpen called for a socialist binational state even before 1967. Now that liberal Zionism has become so fused with two-state-ism that envisioning a one-state Israel is simply anathema, where does liberal Zionism stand in 2021? There are calls to reinstitute a true humanistic, nondiscriminatory Zionism, but I would argue that never really existed. And perhaps it is worth considering that it cannot exist. The barrier preventing the truly equal society many liberal Zionists want may be Zionism itself. There are new calls from the liberal camp to establish a confederation of sorts, an interesting idea, but as of this writing the parameters of such a confederation remain inchoate.

I suggest those who care about liberal Zionism, or Zionism more generally, read Fielder’s Matzpen: A History of Israeli Dissidence. This is not because they will agree with Matzpen; a steadfast commitment to Zionism will put liberal Zionists at odds with Matzpen’s anti-nationalist agenda. Rather, I think looking deeply into Matzpen’s systemic critique of Zionism may help them navigate the rough waters of liberal Zionism’s own crisis and force serious questions about the future of Zionism. Zionism was a powerful, problematic, yet arguably necessary ideology to create a state ex nihilo. But perhaps, today, Zionism is that which is preventing that state from its own ostensible goals, at least for some. Perhaps even though the socialist utopianism and political radicalism that drove Matzpen has largely dissipated in a highly cosmopolitan and technological state, Matzpen’s view was that Zionism is constitutively a chauvinistic nationalist ideology that is by design programmed to systemically benefit Jews over non-Jews in a “Jewish” state. It is an ideology founded on inequality. The latest Nation State Law passed in the Knesset in 2018 is only further proof.

The various attempts by liberal Zionists to curtail discriminatory practices in Israel are noble but will arguably always run up against an ethnonationalist ideology. Matzpen believed that moving beyond Zionism by de-Zionizing the state and focusing on democratic socialism would better enable the country to achieve the equality many of its liberal advocates support. In short, Matzpen may have something to teach today’s liberal Zionists in this critical moment. Perhaps saving Israel requires its inhabitants and supporters to move beyond Zionism. The problem is not two states or one state. The problem is Zionism. Not to destroy Israel, but to save it.

The author would like to thank colleague and friend professor Zvi Ben-Dor of NYU for his sage advice and expertise on Matzpen.

Shaul Magid, a Tablet contributing editor, is the Distinguished Fellow of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College and Kogod Senior Research Fellow at The Shalom Hartman Institute of North America. His latest books are Piety and Rebellion: Essays in Hasidism and The Bible, the Talmud, and the New Testament: Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik’s Commentary to the Gospels.