An Ivy League Powwow

Dartmouth grapples with its original mission to educate Native American and indigenous students

On May 13, Dartmouth College celebrated 51 years of its Department of Native American and Indigenous Studies, along with its annual Powwow—one of several similar celebrations that began showing up at other American universities in the 1960s and ’70s, as the movement for Native American rights gained prominence. But unlike other schools, Dartmouth was founded in 1769 with a royal charter specifically “for the education and instruction of Youth of the Indian Tribes in this Land.” The intention was not to educate these young men for their own sake; instruction was to be of a Christianizing, and therefore European, character. Moreover, the charter also provided for the education “of English Youth and any others,” and in the two centuries that followed, Dartmouth focused decidedly more on these latter two groups. Until the establishment of the new department, the college graduated only 19 recorded Native American students in the two centuries since its founding.

Today, Dartmouth continues to grapple with its history, making strides to include the student population it was originally created to serve, as well as indigenous students from other parts of the world. Since the 1970s, in addition to a Department of Native American and Indigenous Studies, Dartmouth also boasts a Native American Program for its students. The latter is a cultural program that offers a Native American House student residence, hosts both an annual spring Powwow and Hawaiian and Pacific Islander luau, and bookends the Dartmouth experience for Native and indigenous students with a separate pre-orientation and graduation ceremony. Although the Native American faith landscape represents a range of beliefs and practices, initiatives like Dartmouth’s Native American Program that evoke, adapt, and preserve traditional spiritual practices offer something distinct to Native and indigenous students that may influence their overall well-being at the school and beyond.

The college has graduated about 1,200 Native and indigenous students from a variety of tribes since the recommitment to them in 1970. After Dartmouth College commencement exercises this Saturday, June 11, the Native American Program will hold its annual Native American and indigenous graduation ceremony for the class of 2023. This ceremony, overlaid with spiritual and cultural significance, reflects a cultural exchange between tribal groups that took shape in reaction to both official and unofficial external policies of forced migration and acculturation throughout American history.

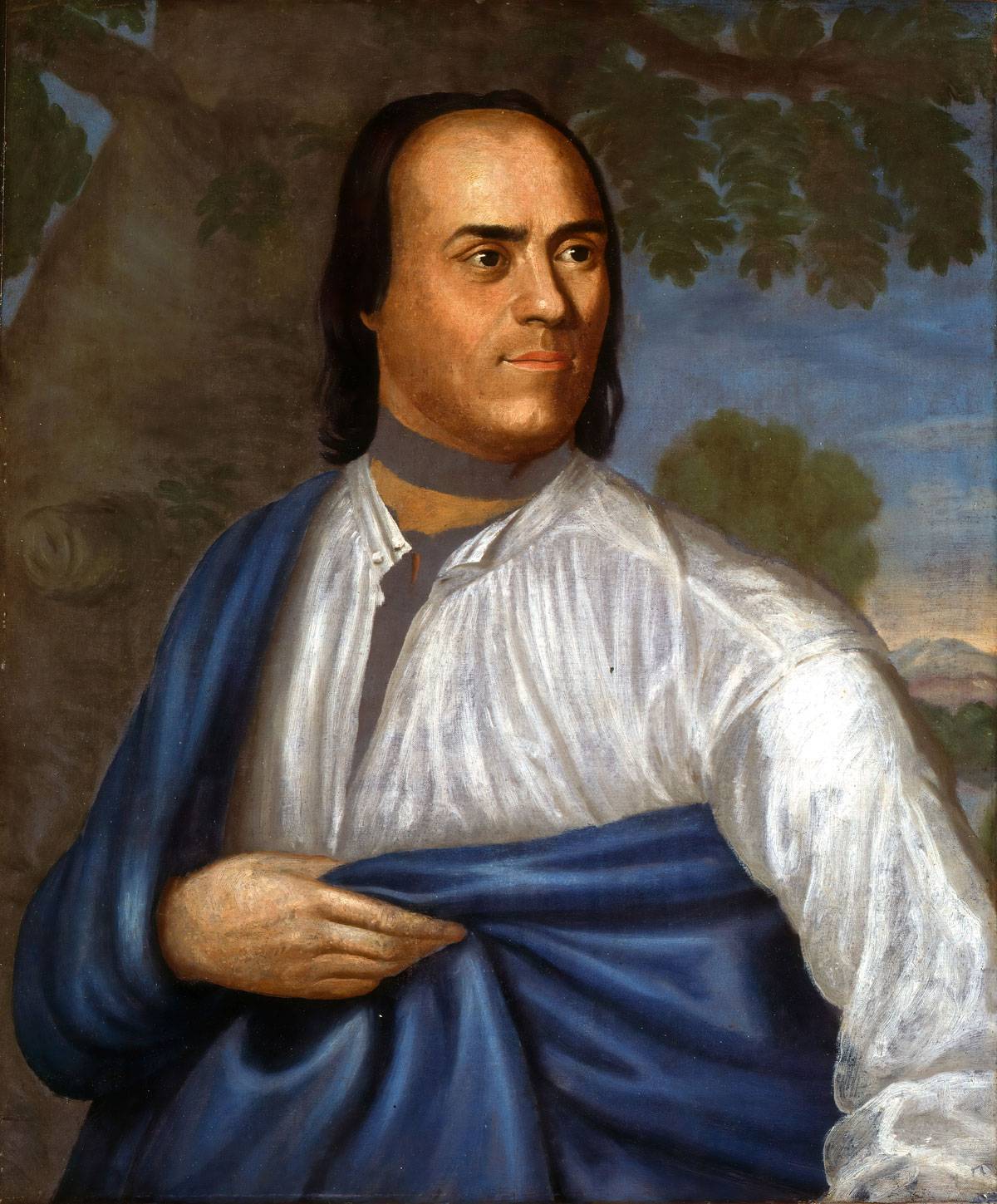

Congregationalist minister Eleazer Wheelock founded Dartmouth College and fundraised for the school with the help of one of his first students, a member of the Mohegan tribe and ordained minister named Samson Occom. However, substantial and intentional efforts to include Native Americans would not begin in earnest until the early 1970s; 1972 saw the creation of what was then called the Native American Studies Program, and inaugurated a conscientious effort to include Native American students.

The numbers tell a story of progress for the college in the decades since it recommitted to its founding principles. Of the 1,125 students in Dartmouth’s class of 2026, 4% are Native American and indigenous, representing 26 tribal nations and communities. The class of 2027 is on track to have a record number of self-identified Native American and indigenous students: 64 incoming students (the previous record is 62 for the class of 2020, according to Associate Director of Admissions Steven Abbott, speaking at the Native American Alumni Association of Dartmouth annual meeting last month). That’s a higher rate than the national average of Native American students at institutions of higher learning, according to recent numbers from the Postsecondary National Policy Institute. Native Americans made up less than 1% of the entire population enrolled in postsecondary education in the fall of 2020; 22% of Native Americans between the ages of 18 and 24 were enrolled in college, compared to 40% of the U.S. population overall in that age cohort.

College and graduate school enrollment among Native Americans has been on the decline since 2010, and completion rates within six years (42%) are lower than the overall national average of over 60%.

Mae Drake Hueston, assistant director of the college’s Native American Program—and a Dartmouth alumna—said in an interview: “Historically, Native students didn’t do well in academic settings, mostly because they were coming from underresourced tribal schools. And when you look at the conditions on reservations, usually they did not get a lot of the funding that was necessary to create really good infrastructure.”

However, within a decade of graduating, Native American students who do complete college tend to enjoy similar outcomes in terms of earnings and wealth accumulation as the national average, according to a 2014 article for the Journal of American Indian Education. The authors noted that “many Native American cultures do express collectivism as a major principle of association and learning. Few Native American students grow up in the tradition of individualism and self-interest,” and indeed for many, higher education represents an opportunity to contribute to their community of origin.

“Powwow brings so much to campus,” said student organizer Shelby Snyder, member of the Navajo and South Ute nations, in a 2022 alumni news article about last year’s 50th anniversary Powwow. “The steps you take while dancing in the arena are also prayers for healing. You’re dancing for those who can’t dance—those who have passed away, those who are sick right now. You’re thinking of all of that collectively, and it’s such a healing space. I think that’s what we really tried to focus on this year—community healing and community bonding.”

For a population that has been subjected to forced campaigns of assimilation, cultural markers and historical artifacts can carry particular resonance.

The Journal article, a literature review, focuses on research into the benefit of Native American clubs at what they term “predominantly white institutions,” or PWIs, saying that they offer rituals that are an expression of culture, which can ground students while putting them in contact with others whose experience may be similar to theirs. As Native American students navigate the culture of competitive individualism that is often pervasive at PWIs, connection to a community that emphasizes cooperation and collectivism can have a spiritually invigorating effect.

And an academic one.

The literature review also found a positive correlation between higher GPAs and Native American students who “became more receptive to social activities,” forming friendship networks that kept them in check academically, and which ultimately connected them more to the institution as a whole. However, that sense of belonging did not necessarily translate into remaining in college past the first year, even for those predisposed to be social joiners. The authors contend that schools lacking Native American clubs or organizations do not offer the kind of cultural reinforcement that could help Native American students contextualize themselves within their new environment. Particularly at PWIs, the authors found the advantage offered by Native American student organizations is the opportunity to engage and become involved with an institution—something that research shows is key to retention—“without threatening their own cultural practices and beliefs.”

For a population that has been subjected to forced campaigns of assimilation, cultural markers and historical artifacts can carry particular resonance.

A variety of tribes are represented at Dartmouth and this year, in addition to traditional drum music, songs, and dances, the annual Powwow also featured a commemoration of the return of Samson Occom’s papers to the Mohegan tribe. In the early 1760s, when Wheelock sent Occom to England to raise the money to start Dartmouth (which he did to the tune of 12,000 pounds, or roughly 3 million pounds—or $3.7 million—in today’s money), the idea was that the polymath and ordained Native American minister would exemplify “what an English education could do.”

That’s according to Colin Calloway, professor of history and Native American studies at Dartmouth. Education meant civilizing: teaching reading and writing in English, “but also instill in them the virtues of Christianity,” he said. Calloway said Occom stayed in England for two years, delivering hundreds of sermons to packed congregations there and in Scotland. But Occom and Wheelock fell out after Dartmouth’s founding, as Occom felt used by the latter, who had ultimately spent the funds Occom raised for the education of Native youth to create yet another white educational institution (Hueston said the revenue brought by wealthy Christian males was a major driver for the college to reorient away from its stated mission so quickly). Somewhat paradoxically, what attempts the school did make to recruit Native Americans in the 18th and 19th century were primarily limited to tribes that had already been Christianized, or had some history of intermarriage or having children with white settlers.

“The definition of education at that time was how do we civilize, acculturate, and make these Natives no longer be Native, but for them to be as non-Native as we possibly could make them?” said Hueston. “Right now, the goal of student affairs offices, which is what I am, what we are, our goal is not to acculturate, and it is not to assimilate, it is to support the students to remain committed to their Native identity,” while they pursue “a quality education.” This is a trend at Dartmouth and at other institutions of higher education she said, that is “kind of counter to why [Dartmouth] was created in the first place.”

Calloway was present at the return of Occom’s papers to the Mohegan tribe, which he said occurred in front of the Mohegan tribal church in Connecticut in April of last year. Built on land that once belonged to Samson Occom’s sister, it was a backdrop replete with symbolism. The sole piece of land in continuous ownership by the tribe, the church was founded as a Congregationalist meeting house in 1831 and it remains, according to the Mohegan tribal website, “an active tribal institution for religious, political, educational, and social functions.” Its continuous possession by the Mohegans proved to be a crucial consideration in granting the tribe federal recognition in 1994, which requires proof of continued, uninterrupted existence of a Native community. This is often difficult, Calloway said, for New England tribes, who “often survived by keeping their heads down.” An eagle feather, a sacred symbol to the Mohegans of purity and idealism, appears above the church’s cross.

The return of the papers, said Calloway, “was more than a gesture. It was the right thing to do.” Dartmouth President Philip J. Hanlon recalled this event in his remarks at this year’s Powwow, calling it a “deeply meaningful moment.”

While many colleges with Native American student populations have powwows, Hueston described particularly robust institutional support for Dartmouth’s. The offices of the president and dean of the college, the DEI office, the Department for Native American and Indigenous Studies, alumni, and student groups all facilitate the annual event.

The college’s use of the word powwow may be surprising to some, given its historical association with the commodified, stereotyped spectacle of “Wild West” shows, popular entertainments for non-Native audiences that featured Native American dancers and performers. The term was popularized when it began to show up in early-20th-century U.S. newspaper ads for such shows, but its origins go back even earlier. “Powwow” derives from an Algonquian word, Pau Wau, which referred to medicine men, but which New England colonists Anglicized and repurposed as a term for a meeting of these men.

The 20th-century powwow evolved in part out of intertribal meetings and collaboration in the 19th century, the result of the U.S. government’s forced migration of Plains Indians from various tribes. Rituals and dances were adapted and spread across the region to form intertribal ceremonies that functioned as reunions for separated families and communities. Yet another, later government relocation of Native Americans in the mid-20th century, intended to remove them from resource-rich lands to jobs in urban centers, caused still more cross-cultural exchange as disparate tribal cultures brushed up against each other, and the intertribal powwows of today came into existence. Concurrently, Native American veterans of the two world wars were reviving intertribal ceremonies to commemorate the fallen and the wartime service of Native American service members. And for the first time, higher education was accessible to Native American men through the GI Bill, which opened up other opportunities beyond the traditional fields of work in the church as ministers, which up until that point had been the primary option offered to those who pursued higher education.

With the evolution of the intertribal powwow, “no matter what culture you came from,” said Hueston, “you could be a part of a Native community,” and have an opportunity to meet in Native dress and meet in large groups with other Native Americans safely, something that was prohibited in most cities and states for most of the year (the Independence Day holiday being the notable exception in many places, when social gatherings of Native Americans in Native dress were permitted). Over time, intertribal powwows became more formalized and solemnized, with rules about conduct, such as prohibitions on drinking and drug use, and maintaining distinctions between performers and spectators. Many of the songs and dances heard at powwows remain rooted in the tribal traditions of the Plains, even when tribes involved are not originally from that region of the country, since the contemporary powwow originated in the Western communities and cities to which many Native Americans were relocated by the U.S. government in the 19th century. Groups write and perform original songs in different languages to present at powwows—the more serious ones to perform during the powwow itself, and more lighthearted ones to play afterward in a more social context.

By her own admission, Hueston is not “a powwow person.” The first powwow she ever attended was at Dartmouth as a student herself in 1983. “You kind of watch and observe and ask questions, and you become familiar with the general things that everybody knows,” she said, “Like, when can I dance, and what do I do when I dance? How do you do the step? And everybody listens to the arena director, and you figure this out, and he tells you, you know, what to do, what’s next, you listen to the emcee so you know the agenda and what’s going on. You learn the styles of the dances by just watching and seeing who all goes out there when dances are called.”

Various distinct traditions are called up during a powwow, but the emotional resonance is unifying for students. “I think in general they feel invisible when they’re students on campus,” Hueston said, and events like the powwow offer an opportunity to celebrate and honor what makes them different. “They miss home. Everyone here who is Native is pretty much far from home.” The powwow, then, is a chance to see others in traditional regalia in a context where it is familiar and affirming. For dancers at a powwow, the dances can function as celebrations or prayers. “For them to be able to do that here, it just makes the college belong to them more,” she said.

Hueston was careful to state that tribes are very different from one another, and their traditions are not monolithic. “We all have various traditions that we use to celebrate,” she said.

A common one, although by no means observed in every tribe, is the robing ceremony, also called a blanketing ceremony. At Dartmouth, it is a feature of the Native American and indigenous graduation ceremony that takes place later the same day as Dartmouth’s commencement exercises. At a robing, someone who has attained an achievement—Hueston said it can be a birth, a graduation, or even winning an election—is honored by receiving a mantle of some type, usually a blanket, which is placed over their shoulders. At Dartmouth, the students are asked to invite someone they admire or honor to robe them. “It’s sort of like a reciprocal honoring,” she said.

This fusion of similar traditions across tribes into a shared ritual is a feature of Native American spirituality and religion, even before the arrival of European settlers. “Cultural boundaries were crossed repeatedly as different peoples shared their sacred stories, songs, dances, ceremonies, and foods with one another,” asserts an article from Harvard’s Pluralism Project on Native American religion, going on to state that religious ritual was frequently bound up in diplomatic and commercial exchange between tribes. After the arrival of Europeans, similar religious traditions and beliefs allowed tribes to coalesce into new alliances in response.

However, despite the similarities, there is no single “Native American religion,” as such. Indigenous religions in the U.S., then, are often differentiated by geography and linguistic similarities, since many practices and beliefs evolved in response to the topography and its related customs (i.e., “the beliefs of the Great Plains” or “the Desert Southwest”). Even so, the variation within even these categorizations makes generalization difficult.

At Dartmouth in the 21st century, this spirit of cultural collaboration and syncretism continues to evolve.

Since its founding, the Native American Program has widened the scope of its programming to include Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders, as well as students from the over 547 federally recognized Native American tribes. It is sometimes referred to now as “the Native and Indigenous Program,” even though the school website continues to use the original name. Academically, the Native American and Indigenous Studies Department also now includes areas of study related to indigenous peoples from Central and South America, Russia, Scandinavia, Australia, and New Zealand. “There are a lot of common occurrences,” said Hueston. “We’re sort of at a point where, does the Native Program actually expand, so that it could include students who are indigenous? Because not everybody identifies as a Native American, or a Native Alaskan, or a Hawaiian Native. There are others that are part of indigenous groups that have that connection to their groups that may not be part of the United States.”

A more capacious, globally oriented iteration of the Native and Indigenous Program would open yet another chapter in Dartmouth’s complicated, but evolving relationship with its Native and indigenous students.

“It’s not a straightforward history,” said Calloway of Native American students at Dartmouth.

Noting that Dartmouth’s recognition of its responsibility to Native Americans coincided with the opening up of the college more generally to women and ethnic minorities in the 1970s, Hueston said, “I feel like this college now, today, really has a 51-year-old history.”

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.