When she was growing up, Diyaanka Jhaveri was part of a group of kids from Dallas who visited London for a global youth festival and spiritual retreat. They played soccer in a kind of spiritually infused youth World Cup, in which the scoring team would pause after each goal to bow to a statue of Shrimad Rajchandra, a 19th-century reformer, saint, poet, and mystic in the Jain religion. He is the guru of a contemporary Jain mystic, Rakesh Jhaveri, who has founded a transnational Jain spiritual movement based in Gujarat called Shrimad Rajchandra Mission Dharampur, or SRMD.

That global youth festival continues to take place every year in Gujarat, where SRMD’s sprawling headquarters is located. The SRMD campus now hosts its own sports complex, where artificial turf is used instead of grass, as a means of extending Jain principles of nonviolence to plant life.

Today, Diyaanka Jhaveri is a 26-year-old teacher in Chicago. (While Jhaveri is not an uncommon name in India, Diyaanka Jhaveri is also a distant relative of Rakesh Jhaveri, who is known to his followers as Rakeshbhai.) Raised Jain in the U.S. (her father emigrated from India in 1992), she credits SRMD’s youth education program, Divinetouch, and its 360-degree approach to life—mind, body, and spirit—with her continued commitment to the Jain religion, an ancient faith that began in India around 2,500 years ago. SRMD’s 202 worldwide satellite centers offer an approach that is not unusual in diaspora Jainism: It differs in some ways from traditional Jainism—it smooths over some of the historical sectarian and cultural differences that affect the way the faith is practiced in India—but also offers points of access to Jain communities outside the country, since its religious authorities are prohibited from traveling via mechanical means, traveling only by foot.

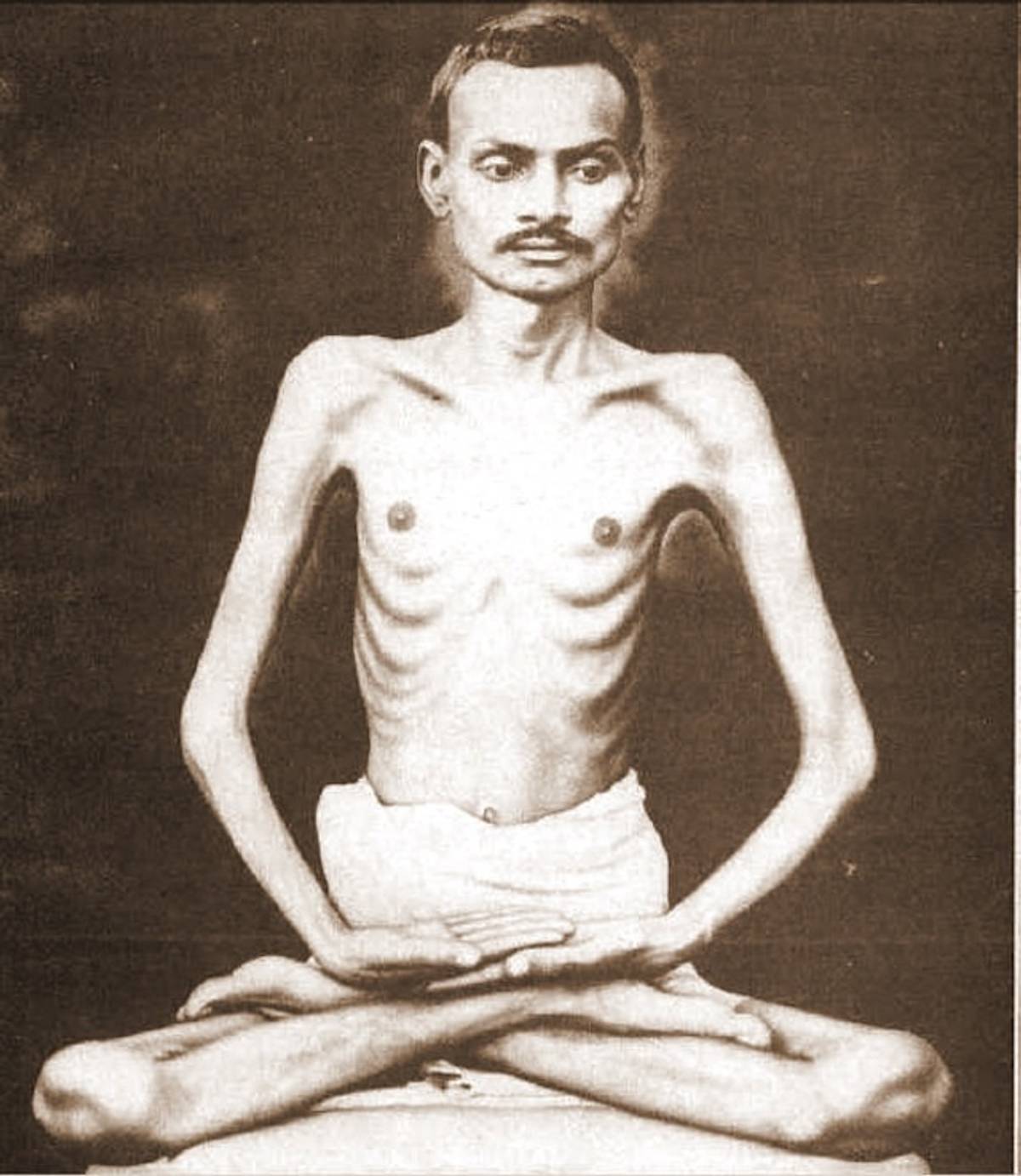

Central to all of this is Rakeshbhai, who was in turn inspired by Rajchandra’s life, remarks, and writings. Through them, Rajchandra developed for Jains from all walks of life a practical, methodical approach to spiritual enlightenment, which he contended would free the individual soul, corrupted from its true divine nature, from the temporal bondage of earthly concerns and consequences. He boiled this philosophy down to six fundamentals, confined to a 142-verse work designed to be memorized, called the Shri Atmasiddhi Shastra, which his followers said he wrote in an hour-and-a-half in 1896, at the age of 28.

19th-century Jain mystic Shrimad RajchandraWikipedia

An intellectual and academic prodigy who demonstrated a profound spirituality from a young age, Rajchandra left behind a prolific body of philosophical and poetic works, and a radical example of detached asceticism, that inspired many after his death in 1901 at the age of 33. His world-renouncing ways—going into seclusion; living, dressing, and eating simply; remaining detached from worldly enjoyments—were to have a powerful influence on a young Mahatma Gandhi, as were his attitudes toward religious tolerance, and opposition to religion as a system of dogmatic principles to be followed by rote and believed merely as an institutional abstraction. Rather, Rajchandra contended that faith in God had to be something personal and single-minded, taking precedence before all else.

As Rajchandra’s 20th- (and now 21st-) century disciple, Rakeshbhai’s reknown as a spiritual teacher grew, and since establishing the SRMD headquarters in Gujarat in 2001, he has expanded his organization’s work there to include an ashram (temple)—where he hosts talks on sacred texts and meditation retreats—as well as a hospital, animal shelter, the sports complex, and education and job programs. He also gives talks internationally, and between 2005 and 2010, he established SRMD centers in North America, the U.K., Singapore, and Hong Kong to serve as study centers and community hubs.

Today, Rakeshbhai fuses his 19th-century guru’s back-to-basics approach to Jainism with an accessible multimedia and multidisciplinary approach: fat-burning yoga videos and mindful eating tips on the SRMD website, as well as online lectures, meditations, and prayers, and social outreach programs.

Over the phone, Diyaanka Jhaveri spoke enthusiastically about her memories of attending an SRMD global youth festival. She recalls U.S.-born kids like her taking care of cows, and because of their grounding in the Jain religious principle that all living things matter, “we knew what it meant to give back, even to a cow.” Conveyed via SRMD’s physical centers worldwide, and its multimedia empire, Rakeshbhai’s 21st-century approach to sharing his guru’s own version of the religion “makes Jainism such an approachable” way of life and practice, Diyaanka said. For a faith that is a minority even in its own country of origin, with a diaspora whose successive generations have little connection to India, the model has proved successful.

Jainism’s exact founding date is murky. Scholarly estimates place it as early as the seventh century BCE, others later, in the fifth century BCE, coming out of eastern India’s Ganges basin. Lacking a single founder, it emerged amid an anticlerical sentiment that was in the ether at the time, which objected to practices, such as priests as intercessors, elaborate ritualistic trappings, and especially animal sacrifice (Jains shared their animus toward the contemporary priestly class with Buddhism, which also originated around the same time and place). Jainism, while distinct from Hinduism as the religion is commonly understood in the West, shares certain concepts and cultural features with Hinduism. It is not an offshoot, but is more accurately understood as having emerged in parallel with Hinduism. “What we think of as Hinduism today emerged quite a bit later,” said Steven Vose—Bhagwan Suparshvanatha Endowed Professor in Jain Studies at the University of Colorado in Denver—in an email. Their shared cultural similarities defy traditional Western understandings of religious denomination: To the extent that Jainism can said to have risen from Hinduism, it is helpful to remember that the term “Hindu” was initially a geographic and cultural signifier, a Persian term for anyone who lived on the other side of the Indus River from the Persian Empire’s holdings (it was later picked up as a religious signifier by the British imperial census-takers).

Even today, while Jains maintain a separate set of scriptures and religious texts, and venerate different figures from Hindus, they often closely associate with Hindus, whose ceremonies, rituals, and narrative stories their own can resemble, and with whom they share in common the Sanskrit language. The very name of the faith derives from a Sanskrit word ji—meaning “to conquer,” which represents Jainism’s focus on ascetic renunciation of worldly cares and priorities.

Examples of similarities include the Hindu figures Rama and Krishna, who also appear in Jain texts, as well as the two faiths’ shared principle of karma, the cosmic law of cause-and-effect with long-lasting impacts on the soul. However, while the names of the people and concepts are the same, they mean different things to Jains than they do for Hindus. For example, Jains recontextualize the Hindu heroes Rama and Krishna by their relationship to different figures in Jain history. Karma is also understood differently in Jainism, where it is a substance (as opposed to a ledger of good deeds that must be balanced, in order to be freed from a cycle of rebirth, as it is in Hinduism), with particles that can be picked up over time through one’s actions. In the Jain understanding, accumulated karma weighs the soul down, and must be jettisoned to attain final liberation, hence the emphasis on ascetic practices like fasting and isolated retreats, as well as meditation and acts of service to others. The essence of Jain belief in intentional, pure practice of Jain religious principles and its moral code is on display in its total commitment to nonviolence, which extends to a practice of vegetarianism.

Rakesh Jhaveri, the founder of Shrimad Rajchandra Mission Dharampur (SRMD)Wikipedia

Jains attribute their canonical teachings to tirthankars, human beings who they believe to have attained omniscience, and who laid down the principles of Jain thought and belief. Although they are not deities, Jains pray to tirthankars in hopes of emulating their perfection and karmic detachment. (Rajchandra is believed, in a past life, to have been a close associate of the last tirthankar, who lived in the late fifth century BCE, and from whose teachings his are said to be derived.)

Over the phone, Vose gave me a crash course on Jain history up to the present day, explaining the complex disputes that emerged after the last tirthankar, which gave rise to its existing denominational differences (for example, delineations over idols versus no idols, and over white-robed monks and nuns versus naked monks).

There are estimated to be fewer than 6 million Jains worldwide today, with the majority in India (around 4.5 million, according to the last census), where they constitute about 0.4% of the population. In the 20th century, Jains began arriving in the United States after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened up U.S. immigration, increasing South Asian immigration in particular. Today, Jains are estimated to number between 150,000 and 200,000 in the United States, with their larger population centers in Chicago, Southern California, Texas, and New York.

Jains in the U.S. today are largely white collar, which is unsurprising given Jains’ status in India, where, according to Vose, they are one of the most literate religious groups. This set of circumstances has its roots in history and geography, in south and west India, where Jains migrated from their original home in the eastern Ganges basin and prospered as merchants. As a religious minority, they often found themselves buffeted about by external political and military events in India. Vose contends that because merchant capitalism attracted elites, it offered a degree of prestige and protection to Jains, whose status as arrivistes in the central, western, and southern parts of India would have otherwise been precarious.

While even lay Jains have a set of vows to anti-violence, the ascetics, known as Maharaj Sahebs, and their communities represent “the foremost living authority on Jain text and knowledge,” to whom the Jain community looks for spiritual guidance, and who are charged with handing down teachings. However, because they can travel only by foot, Jains must travel to India to meet with them face-to-face.

“Temples become really important centers for teaching children. It’s sort of the very big crisis for diaspora,” Vose said, as Jainism spread around the world, but their teaching authorities were prohibited by their vows from traveling by any means other than walking.

Like many diaspora and immigrant communities, Jains worried about handing down the faith to their young people. “The people who migrated here post-1965 started having kids,” said Vose. “And you know, watching their kids, like, not really understand a lot of things.” The way things their parents had always done things in India “didn’t always work.”

This predicament led to reform in the mid-20th century, according to Vose, including the creation of a sort of semi-ordained monastic order of men and women, called samans and samanis, who can travel abroad to expatriate Jain communities who would otherwise lack traditional in-person religious leadership. Other solutions included the creation of transnational organizations, such as the Federation of Jain Associations in North America (JAINA), which serves for the umbrella organization for the 72 Jain centers that span the United States and Canada—JAINA’s youth branch, the Young Jains of America, has produced a helpful series of Jainism 101 videos—as well as the Rakeshbhai’s international SRMD satellites and online presence.

The U.S. has also played host to new, international forms of spreading and preserving Jain tradition, notably two Jain monks who either renounced or redefined their vows to immigrate to the U.S in the 1970s. The Harvard Pluralism Project calls these men, Sushil Kumar and Muni Chitrabhanu, “iconoclasts in India”: “They became institution-builders in America,” where they established “neo-orthodox” institutions that were “seen as more open-minded, realistic, and practical than traditional Indian Jain orthodoxy, while simultaneously preserving the deep spirit of the Jain tradition.” While Kumar and Chitrabhanu helped found and establish various cultural and religious sites around the U.S., their Americanization of Jain practice to make it more accessible outside India (downplaying asceticism, ritual, and intrafaith sectarian differences, in favor of emphasizing more universal value-based practices like vegetarianism and nonviolence) garnered criticism for diluting the faith.

Criticism of Kumar’s and Chitrabhanu’s work in the 1970s, to make Jainism something more readily understood by their contemporaries inside and outside the faith, is echoed today in critiques of SRMD and Rakeshbhai, whose social media presence Vose said really expanded in the 2010s.

“He’s also probably the most controversial Jain religious leader today,” Vose said of Rakeshbhai. “He really preaches a kind of a Jainism that makes sense to people’s everyday lives,” a practical self-help approach that includes meditation, and handling the stress of everyday life.

Rakeshbhai is disinterested in older, traditional sources of authority, and de-emphasizes things like caste, which is an important topic for Jain audiences in India. His flattened Jainism, which is inflected with his own personal brand, and which incorporates different academic, spiritual, and philosophical disciplines, has made him popular with young Jains in the Anglosphere.

Jain practitioner Jasvant Modi is a retired doctor who first came to the United States from India in the early 1980s. In 2010, he became active in founding Jain chairs of study at major U.S. universities. When asked about Rakeshbhai’s appeal, he acknowledges that SRMD is not representative of the Jain religion in the U.S. as a whole. “His ideas are progressive and liberal compared to orthodox Jain people who believe something a little bit different,” Modi said, but it is less of a controversy than a “difference of opinion.”

Rakeshbhai’s belief that his guru, Rajchandra, is the reincarnation of a close disciple of the last tirthankar and direct conduit of his teachings—as well as his flattened approach to devotional practices—set him apart from the mainstream.

Modi explained Rakeshbhai’s importance to contemporary U.S. Jains: “He has an ability in terms of speaking and explaining complex Jain principles into a simple language where people can understand and follow.”

Rakeshbhai’s videos for youth on the SRMD sports page include titles like “A Quick Tip on How to Change Your Habits” and “How to Achieve Growth in Any Field,” sounding much more like a self-help guru—something Americans understand—than an actual guru.

“The biggest thing that I would say that he does that really appeals to especially the American audience is that he’s really big on charitable work,” said Vose. While Jainism has a tradition of service called Seva, which traditionally meant service on and around the grounds of an ashram, or house of worship, “Jains are not big on Seva, historically,” he said. “[Rakeshbhai] has made Seva part of his spiritual platform, but it really looks like the charitable activism that you would expect from, like, American organizations.”

Rural hospitals, schools for the academically and caste-disadvantaged, and public health initiatives at the SRMD ashram in Gujarat all tap into professions that attract younger Jains. “He’s got a willing cadre of young doctors who go to the hospitals for a month or so out of the year to work there,” said Vose.

American SRMD centers also advance this concept of service. “Community service and religion go hand-in-hand,” said Diyaanka’s father, Devang Jhaveri, who has run the Divinetouch program in Dallas for a decade. He told me about past years’ initiatives, community service trips, crocheting items for children with cancer, and working with food banks.

Diyaanka Jhaveri agrees: “The reason why I’m still a teacher post-pandemic,” she said, “is this drive to help others,” which she credits to her parents and the influence of SRMD and its guru.

Divinetouch lays a foundation in religious literacy, teaching younger children about the major world religions, then instructing middle-grade children in Jain religious principles, and finally guiding teens to apply the earlier knowledge gained to real life situations. It is “a really good way for someone who’s been born and raised in this country,” Diyaanka Jhaveri said, to see how Jain principles pertain to real life. As a teen, going through an early iteration of the teen program, Spiritualtouch, she said she was able to understand how ahimsa, the Jain commitment to nonviolence, extended beyond “don’t hit,” to the idea that “my words and my thoughts can have implications,” which she said were a big help as she navigated her drama-filled teen years.

Diyaanka Jhaveri also said that when she was a teen, having the foundation of a Jain principle—the multiplicity of viewpoints—helped with conflict resolution at home, too. “Everybody kind of understands where the other person is coming from,” she said, “at least in theory.” The English-language religious education she received through SRMD youth programming helped create a shared emotional vocabulary with her family, she said. “It’s not like we’re throwing around Sanskrit Jain principles all the time,” she said, but she was able to appreciate that parental advice was based on values that she herself knew and understood.

Today, as a teacher who works with 12- to 14-year-olds, she said the valuable strategies that she learned as a teen herself—anger and stress management, along with viewpoint tolerance—have equipped her with valuable practical tools she still uses.

Devang Jhaveri still volunteers with Divinetouch, which he said is especially valuable now, with teen mental health issues at a societal peak, by giving young people a “safe environment to talk about their daily challenges” through a Jain lens.

“What’s so amazing,” Diyaanka Jhaveri said of SRMD’s service component, and Divinetouch youth programming, is the way in which it reaches young people who aren’t ready for complex theology. They see the positivity of their guru, Rakeshbhai, and the effects of the principles learned in class when they apply them in real life, which in turn, she said, makes them curious to know more about the underlying principles.

Both Jhaveris are keen to express Rakeshbhai’s influence, especially on the young, who may encounter him in person at a retreat at his mission in Gujarat, at a global youth festival, or during one of his frequent visits to the United States. When “blessed with a conversation, or a piece of advice” from him, Diyaanka Jhaveri said, or when listening to his lectures and stories in English, “it makes Jainism such an approachable” way of life and practice. When we spoke, she was in training with SRMD to become a yoga teacher.

Like many religious diasporas, Jains are grappling with how to keep subsequent generations in touch with the culture and religion from which they emerged. Outside of SRMD, study groups for young and old alike are common. The very fact that Rakeshbhai travels at all, unlike traditional Jain vowed monastics, makes him more appealing and accessible to American Jains, said Modi.

Within Jainism, Rakeshbhai is sui generis. In the mold of his iconoclastic 1970s forebears, Kumar and Chitrabhanu, he is a modern spiritual authority, something altogether different from the traditional religious authorities—from a monk, who cannot really travel, or even from a saman or samani, who can. Rather, he operates outside traditional Jain structures, traveling around the world to speak to his followers, and claiming for himself an appeal to the authority of his guru, Shrimad Rajchandra, whose discipline, according to Vose, “has always been an independent and frankly intellectualist streak within modern Jain life.” By adopting his 19th-century guru’s philosophy for a new, modern audience, Rakeshbhai has developed “a comprehensive devotional practice that’s moved out of just the intellectual work,” said Vose, and infused it with more devotional and popular forms of worship and spirituality.

By returning to first principles, embracing technology, and (literally) meeting its followers where they’re at—particularly the young—SRMD appears to have found a way to engage U.S.-born Jains.