New Jewish Rituals Offer Comfort to Women Who Have Had Abortions

‘Not being able to process it religiously makes it a very hard experience. We thought it’s important to give it a voice.’

Forty years ago, in a moment of what she later described as “self-centered professional zeal,” Batya had an abortion. She was 22 years old, a grad student about to leave the country for an archaeological expedition. “I did it in panic. I always wanted to have children, but I just wasn’t ready,” said the now-mother of three, who agreed to speak about her abortion only if she was identified by her nickname. That abortion turned out to be the first of two: The second occurred later, when her first marriage was falling apart. But afterward, she was troubled by feelings of grief and loss that she admits, many years later, are still partly unresolved.

“I haven’t been wallowing in misery for the last 40 years,” Batya told me. But she did think that a “spiritual, ritual way,” of marking the decision would have helped in resolving those feelings. So, when a young relative recently chose to have an abortion, Batya assisted her in finding a Jewish ritual to help her come to terms with the decision. Trawling the Internet turned up nothing at first, but then she found something: an immersion in the ritual bath offered by the Mayyim Hayyim (Living Waters) community mikveh in Newton, Mass. “I felt a certain sense of relief and comfort, in the fact that others had thought of this, and that there could be a certain solidarity and community,” Batya said. “We mark every other experience in a Jewish way; why not mark this one?”

The founders of Mayyim Hayyim concur, because they have created one of the very few Jewish rituals for a woman marking the termination of a pregnancy. The rite, written by Matia Rania Angelou, Deborah Issokson, and Judith D. Kummer—a poet, a psychologist, and a rabbi, respectively—is so exceptional that women who discover it are often astounded to find that it exists. It consists of three immersions in the mikveh, interspersed with short blessings and prayers, and it opens with a kavanah—the “intention” by which a person prepares herself to do a mitzvah in the fullness of her heart—asking God for help “to begin healing from this difficult decision to interrupt the promise of life.”

Within the Orthodox Jewish tradition, abortion is generally permitted only when the pregnancy would endanger the life of the woman, although some authorities allow it in cases of severe genetic disorders, such as Tay-Sachs disease. Conservative and Reform attitudes toward abortion tend to be more tolerant, allowing it in cases of severe psychological harm as well. Even so, “abortion is one of those issues that’s on the dark side of fertility,” said Elana Sztokman, executive director of the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance. “People, especially in the religious Jewish community, often do not like talking about it. Even though Judaism has quite a humane approach to abortion, the Jewish community as a whole still often does not speak openly about abortion. Many women who have had abortions experience solitude and loneliness and even a fear of social judgment.”

The result is that many Jewish women who choose abortion go through the ordeal alone, in silence and fear and with no spiritual recourse or guidance. While prayers for women have been composed to mark virtually every other life-changing experience—including miscarriage, infertility, and menopause—the notion that some form of religious observance is necessary, desirable, or acceptable for abortion is hard for many people to fathom. They may believe that abortion is a procedure that the woman has chosen, often for “elective” social reasons, and not something visited upon her, as with an unintended pregnancy loss. A Jewish ritual for abortion is also complicated from a feminist point of view: Forty years after Roe v. Wade—and decades of often-violent anti-abortion activism and restrictive state legislation—some feminists don’t necessarily want to acknowledge the notion that abortion may be associated with feelings of grief, loss, or regret that may last for years.

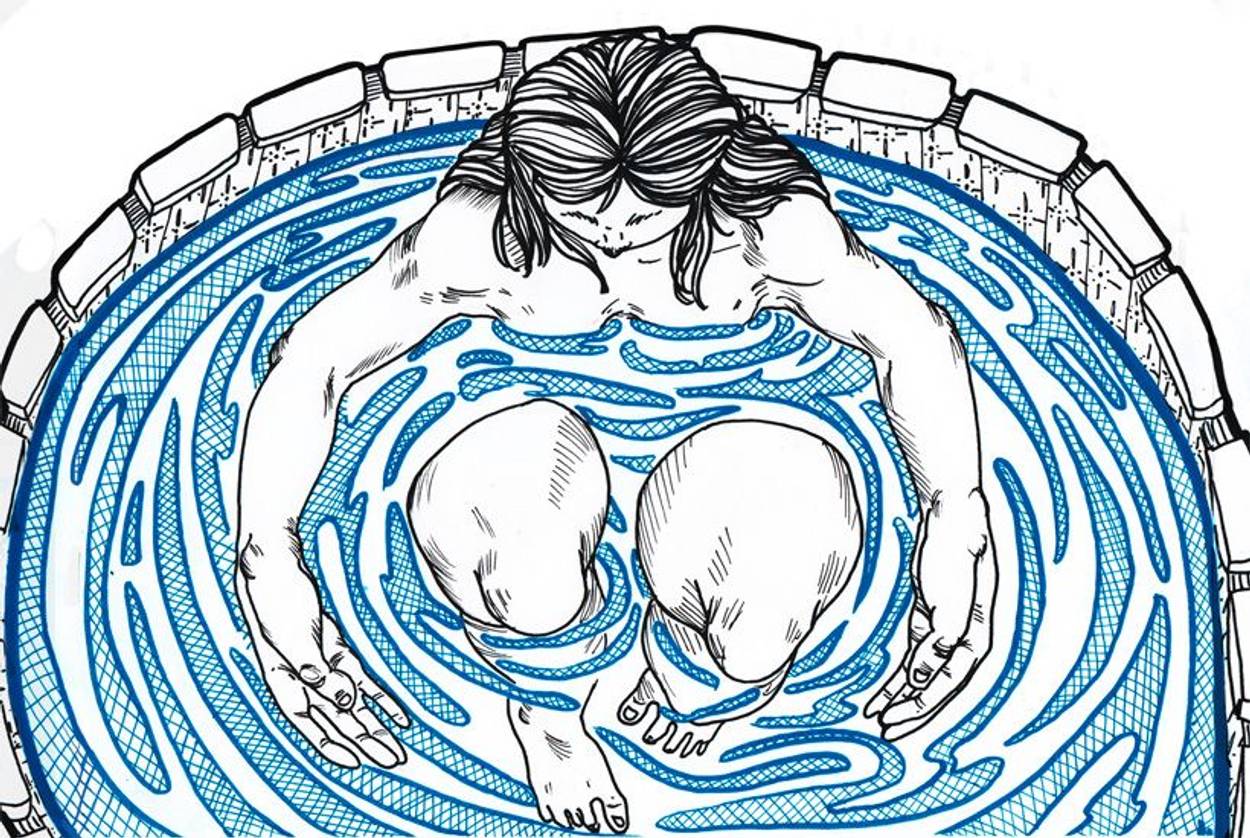

Yet some women who have chosen abortion, even if they are sure that it is the right choice at the time, find themselves dwelling upon the decision, even years after the procedure, and often on its anniversary or in the weeks leading up to it. Immersing in the mikveh, said Mayyim Hayyim’s executive director Carrie Bornstein, can offer the woman an opportunity for separation and transition: “Oftentimes it’s helpful for people to say, ‘I’m going to move to the next stage of my life, whatever that might bring, and I’m not going to let that experience define me or take me over.’ ”

From a halachic point of view, going to the mikveh after an abortion is, in fact, required for a married woman, Bornstein adds, since she has an obligation to immerse after uterine bleeding in order to enter a state of taharah—ritual purity. Aliza Kline, the founding director of Mayyim Hayyim, claims that there are “probably scores, if not hundreds, if not thousands of women” who have gone to the mikveh after an abortion. “Having to go and be dishonest as to why you are going seems to me completely counterintuitive to the whole notion of mikveh, during which you are naked, vulnerable, and exposed,” Kline said. “The notion that the community is closing their eyes and plugging their ears and saying ‘la la la, this isn’t happening,’ is really not helpful.”

Mayyim Hayyim is not the first institution to offer a Jewish ritual for abortion: In 1998, Conservative Rabbi Amy Eilberg published a post-abortion ritual in Moreh Derekh, the Rabbinical Assembly’s “Rabbi’s Manual” that serves as the Conservative community’s guide to Jewish life-cycle events. Eilberg, who is now on the faculty of United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities in Brighton, Minn., says she wrote the “grieving ritual following termination of pregnancy” out of “a general Jewish feminist awareness that the tradition was created substantially by men . . . who didn’t necessarily know what women, if they had agency, would want to have included in the tradition.”

Eilberg recalls that in her work as a hospital chaplain in the early 1990s, she met many women who had experienced a pregnancy loss or termination. “Whether it was because of an abnormality, whether it was because conception was unintended, and the mother discerned that she was not going to be able to take care of this baby, or God forbid it was a rape, whatever the circumstances, I frequently encountered grief and sometimes significant ambivalence of ‘am I doing the right thing?’ ” These women often sought reassurance from their loved ones or community, she said, “that there is some way to sanctify the decision that I’ve made.”

Eilberg’s ceremony, which does not specify the reason for the termination, is designed to take place in the rabbi’s study or at the woman’s home, in the presence of trusted family and friends. It includes prayers and passages from Psalms, and, most significant, a “rabbinic meditation” that acknowledges that a choice has been made, and that sometimes it is a “terrible choice that was no choice at all.” It ends with words from Deuteronomy 30:19, which we read from the Torah this year on Aug. 31, the double portion Nitzavim-Vayelech: “Choose life, that you and your seed may live.”

Opening the door to hope and renewal is a theme that runs through a recent post-abortion ritual devised by Rabbi Tamar Duvdevani, currently a graduate student at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, Ohio. The ceremony, composed in Hebrew, appears in Parashat HaMayim: Immersion in Water as an Opportunity for Renewal and Spiritual Growth, a book published in Israel in 2011 including immersion ceremonies, edited by four Reform Rabbis: Alona Lisitsa, Dalia Marx, Maya Leibovich, and Tamar Duvdevani. The ritual draws its inspiration from the tashlich (“casting off”) service performed on Rosh Hashanah, in which Jews gather by a stream of flowing water and toss their sins (along with a pocketful of breadcrumbs or crusts) into the river or sea.

Rabbi Dalia Marx of Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem admits that the editors debated at length on whether to include an abortion ritual in the collection. “If you write a ritual for it, it means that you embrace it, or you think it’s legitimate,” she said. “And obviously, most of us think that it is legitimate; it’s unfortunate, but it’s something that happens to many women.” It’s also an experience that many women go through alone—without a partner, friend, or family to accompany them. “Not being able to process it religiously makes it a very hard experience,” Marx said. “We thought it’s important to give it a voice.”

As the introduction to their service explains, it was precisely because of the secrecy attached to abortion that the editors decided to create the ritual to sustain the woman through her distress. It’s also why they recommend sharing the ceremony with a group of friends and a leader, who introduces it with words of reassurance: “We have gathered here to mark the choice of [woman’s name] to abort the fetus in her womb. We know it was not an easy decision, and we offer her our support.” The woman recites passages from Psalms and from the daily Amidah prayer and declares her intention to bear in mind “the sprout of life” that grew in her womb and announce her choice not to let it flourish. She throws breadcrumbs into the water, and the leader responds: “This stream of water is like the stream of tears that washes away pain and purifies your heart, for forgiveness and a new beginning.” The woman then immerses herself in a stream of running water.

The choice of running water—the sea, a spring—over a traditional mikveh is deliberate: “Mikveh in Israel is a very loaded, Orthodox institution,” said Marx, adding that the mikveh lady may have instructions not to let an unmarried woman immerse. Yet one Orthodox mikveh-in-the-making in Jerusalem, the Eden Center, is open to the idea of immersion after abortion. Naomi Grumet, the founder of the Eden Center, explained that “mikveh is a connection to eternity, to creation, to the cycle of life, because a mikveh has to come from natural rainwater. The mikveh itself represents the womb, represents rebirth, represents reconnection.” While the Eden Center would not necessarily create its own abortion ritual, it might, Grumet said, “provide a platform if women will find it meaningful,” perhaps by providing Mayyim Hayyim’s ceremony in translation.

The Eden Center may prove to be the rare Orthodox organization willing to consider such a ritual. As Meira—a woman who had an abortion recently and also asked to use a nickname—explained, such a service would be unthinkable in the Orthodox mikveh that she visits monthly. Earlier this year, Meira decided to end the pregnancy of a “very planned, very wanted fourth child,” following a “bad prenatal diagnosis.” She looked for a feminist ritual and found the one offered by Mayyim Hayyim but couldn’t imagine explaining the service to her mikveh attendant: “Mikveh and abortion are two completely contrary spaces for me, because I’m so used to mikveh being this profoundly Orthodox space,” she explained. “The people who I think of who are pro-choice—who are people who have either had, or would have an abortion, even if many of them are vibrant, observant Jewish women—are a very different set of people in my mind from the women who consistently go to mikveh.” Even so, she said, the fact that the ritual exists at all “gives me a certain level of peace.”

Discomfort over the place of abortion within Judaism—or the need for a Jewish ritual to mark it—is not confined to Orthodox circles. “When, God forbid, a woman has to terminate a pregnancy due to her own physical and emotional health crisis, or because she was raped, or because the fetus was terminally ill, then I think these rituals could play an important role in her healing and renewal,” said Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky of the Conservative synagogue Ansche Chesed on New York’s Upper West Side. But he added a caveat: “Now, I suppose that this is true only of those regrettable instances when one terminates a pregnancy for responsible and defensible reasons. I do share the view of many people that purely elective abortion runs afoul of many Jewish values and norms.”

Is a formal post-abortion ritual really necessary? Aliza Lavie, Bar Ilan University academic and author of A Jewish Woman’s Prayer Book, wonders why a woman needs official sanction to say a prayer after terminating a pregnancy. “She decided to do it, so why does she need to ask permission for prayer from a rabbi?” asked Lavie, who is currently a member of the Israeli Knesset representing the party Yesh Atid. “Why can’t she decide for herself? This is her reality, she knows her situation, she knows her needs, so she is the one to decide what to pray, and when, and whatever.” Like our biblical foremothers and forefathers, who composed their own prayers, she, too, can write her own, Lavie suggests—as women have done throughout the centuries.

Lavie believes that the search for such a ritual is a very “modern” quest, in the sense that abortion was rarely an option for women in past centuries. That such ceremonies are springing up now—and not 20, 30, or 40 years ago—also reflects the flowering of new feminist ritual since the 1980s, noted Eilberg. They were not composed earlier, she believes, perhaps because of the political complexity that surrounds the issue: the vexed question of how to reconcile a pro-choice, feminist position with a Jewish ritual that acknowledges the sense of loss and ambivalence that may follow an abortion. But Eilberg doesn’t see the contradiction: “This is not about politics; this is about a mother’s experience,” she said. “Prayer isn’t about moral logic; prayer responds to the human being’s need for God, for comfort, for community. And that’s the spirit in which I offered it—despite the fact that I personally very much believe that abortion needs to be available in a healthy and safe way for women who need it.

Josie Glausiusz is a science journalist whose writing has appeared in Nature, Scientific American Mind, and National Geographic.Follow her on Twitter @josiegz