The Jewish Superman

In his day, Zishe Breitbart rivaled Houdini as he awed audiences with feats of strength

A century ago, in 1923, a Jewish strongman named Zishe Breitbart was having a very good year. He starred in an Austrian silent film called The Iron King, but spent much of the year touring the United States—en route to becoming an American citizen. Capitalizing on the popularity he’d earned in Europe in previous years, he launched a correspondence course that detailed his muscle-building and nutritional eating routines; he was the first strongman to offer such a mail-order bodybuilding program.

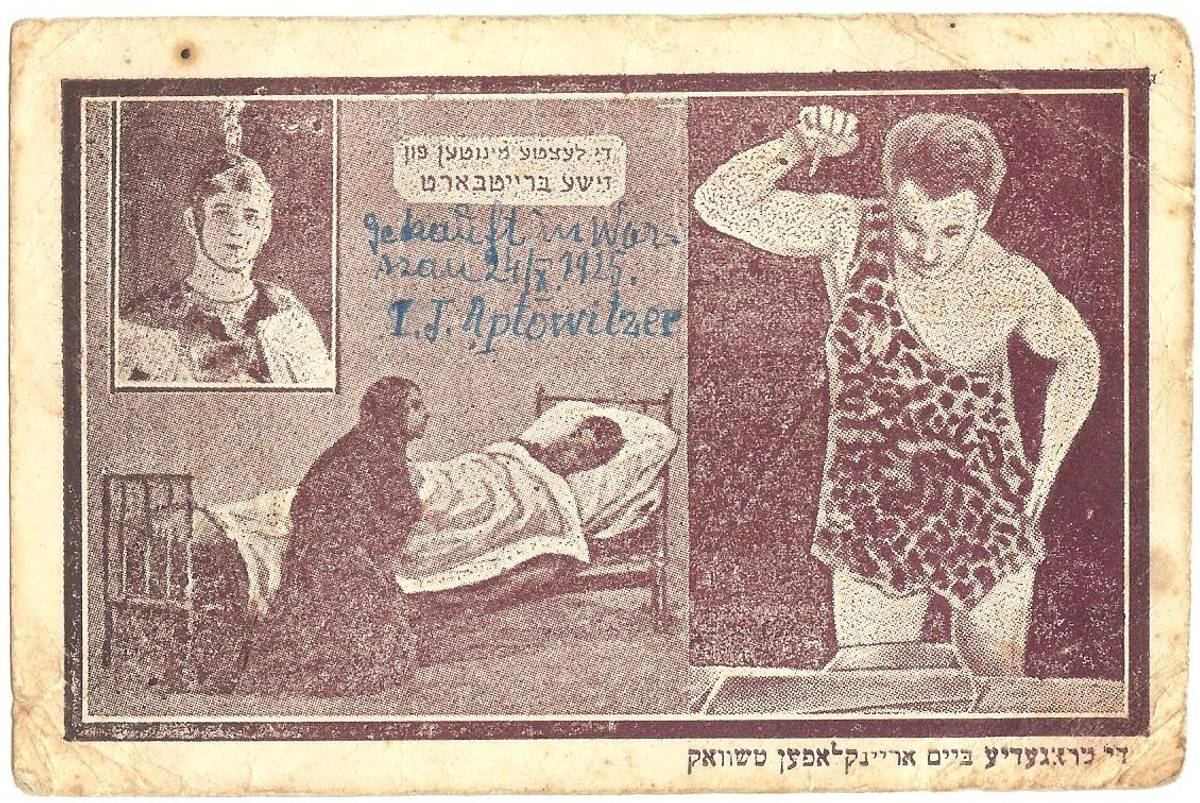

Breitbart was, by this point, a celebrity and something of a cult hero on both sides of the Atlantic. His renown as both a showman and a public Jewish figure—he wore a Star of David on his costumes—made him an international celebrity without precedent. According to the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, “During the few short years of his reign as Europe’s ‘Iron King,’ a Breitbart craze resulted in two German films and a Yiddish screenplay, product endorsements, a physical-culture correspondence course, jokes, poems, songs, and even Christmas cards.”

Two years later, he was dead. And a hundred years later, his name is mostly forgotten. But his spirit lives on. He is as important—or should be as important—to comic book fans, whether they know of him or not, as he is to high-culture artists like Werner Herzog. And he is proof that no matter how many books are written by the People of the Book, no matter how much we excavate our history, there are still important figures left unknown, men and women we would do well to rediscover.

When Jews acquired citizenship in European countries in the 19th century, Jewish creativity and ability exploded into fields that had formerly excluded them. One of these was athletics. Among the most pronounced examples of a Jew who made his mark in athletics was the Polish Jew Siegmund “Zishe”” Breitbart.

As an outstanding exemplar of the “muscle Jew,” he was part of a movement meant to alter European Christian perceptions of Jews as weaklings and unathletic—and, more important, to instill a sense of pride and solace to Jews fearful of what the future held for them.

Siegmund Breitbart was born on Feb. 22, 1883, into a poor Orthodox Jewish family in Lodz, Poland. Many members of his family were professional blacksmiths, and he grew up in a rough-and-tumble working class neighborhood. As he grew, he became immensely strong, leading to work as a strongman. He performed in circuses and fairs, and his most popular feats included bending iron bars around his arm and pounding long nails into thick boards with his bare fist.

During WWI, Breitbart served in the Russian army. He was captured by the Germans while serving on the Eastern Front and served time in a prisoner of war camp. After his release, he remained in Germany and lived on money he earned from performing feats of strength at local fairs and markets.

It was at one such 1919 performance that he was seen by the owner of the Busch German Circus, famed for featuring performances by the great Jewish performer Harry Houdini (born Erich Weiss). The circus owner spotted Breitbart and hired him to perform as its opening act. He joined the circus as a strongman and was the first strongman to be hired by the circus as an opening act. Standing 6-foot-1 and weighing 225 pounds, he was billed as “The Strongest Man in the World.” Soon, his act drew larger audiences than Houdini’s.

Breitbart was deeply committed to his Jewish faith and heritage, and he spoke glowingly in Yiddish to the Jews in his audiences about the Zionist settlements in Palestine. An enthusiastic Zionist, he often performed with the blue and white Zionist flag draping the stage. Zishe openly supported Vladimir Jabotinsky and the goal of an all-Jewish army. According to Sharon Gillerman, in her 2002 scholarly article “Samson in Vienna: The Theatrics of Jewish Masculinity” (from which much of this information comes), he allegedly met with Jabotinsky to discuss plans whereby Breitbart would become the commanding general of a future Jewish army in Palestine.

And although Breitbart was cognizant of the rising tide of antisemitism in Germany and Austria, he fearlessly wore the Star of David on all his costumes. Despite his overt identification as a Jew, he still drew large non-Jewish audiences in Berlin, Prague, and Warsaw. According to one contemporary magazine article, “Not only do gymnasia students and high school girls talk about him, even first graders know how strong Breitbart is.”

But throughout his career, Breitbart’s most devoted and enthusiastic fans were the Yiddish-speaking Jews of pre-Holocaust Eastern Europe. To them, he was a great Jewish hero who embodied their hopes and aspirations. And many viewed him as symbolizing an important response to the increasing number of antisemitic attacks that arose in Europe and America during the 1920s and ’30s.

The Yiddish-Jewish press venerated Breitbart, and even Orthodox and Haredi rabbis admired him. Gillerman quotes a talk he once gave in Brooklyn, in which he told the audience, “If I meet an antisemite, I will take care of them. Let them come to me. If I meet them, I will tear them apart like this.” He then tore apart a horseshoe he was holding. He ended his talk by saying, “I will break them like a match.” The tailors, peddlers, and young people in the audience rose as one and cheered and applauded.

Zishe Breitbart died in October 1925, eight weeks after he accidentally injured himself during a strongman demonstration in Germany. He had stabbed himself in the knee with a spike that he drove through five 1-inch oak boards using only his bare hands. The wound became infected, which led to blood poisoning. He endured 10 operations, and both his legs were amputated. But the infection proved too severe. (Like Houdini, this paragon of physical vigor was not to die of natural causes.)

Breitbart was buried in the Adas-Yisroel cemetery in Berlin, and, according to the newspaper Doar Hayom, published in mandatory Palestine, thousands attended his funeral. “Over a radius of several kilometers, the roads surrounding the cemetery were lined with hundreds of cars,” according to the article. “The elderly caretakers of the cemetery claimed that they could not remember ever having seen such a large funeral in Berlin.” Ezra Munk, the chief rabbi of Berlin’s Orthodox community, referred to Breitbart as a “modern Samson, the hero who also possessed a tender demeanor.” Munk declared that “for a man who broke chains, it was enough for one person’s good word to render his heart soft as butter.”

Breitbart’s physical culture correspondence course, which was based in New York and London, outlived its founder and continued to operate until 1966. Breitbart had an even longer afterlife. In 2001, Werner Herzog directed the film Invincible, which is all about Breitbart; the Jewish hero is played by the Finnish strongman Jouko Ahola. And it’s quite possible that the young Joe Schuster and Jerry Siegel modeled their new comic book hero, Superman, in part on Zishe Breitbart, who had toured America in 1923, when the future comic book creators were young boys; his show at New York’s Hippodrome drew 85,000 spectators, and he was a national sensation. The future comic book geniuses surely know of Breitbart, who was the most famous strongman in the land, and fellow Jew to boot.

Breitbart knew he was a man for the ages. While in the United States, he applied for citizenship, which was granted the following year—just as the United States’ new immigration restrictions were about to be put in place, closing off the mass immigration of Eastern European Jews. Had Breitbart lived, it seems he would have relocated to the United States, a move that would have saved his life, much as he, with his passionate devotion to the Jewish people, was always thinking about how to save ours.

Robert Rockaway is professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, and the author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters.