Yidl, Get Your Gun

But don’t forget your God

AP Photo/Elias

AP Photo/Elias

AP Photo/Elias

In the wake of the Oct. 7 attacks by Hamas, and the vile antisemitism that has since surfaced in our beloved American diaspora and elsewhere, many Jewish individuals—my wife included—feel the call to get a gun as a means of self-defense. You hear about it in shuls, and read about it in Jewish magazines and newspapers. Even in the hallowed precincts of Torah-towns like Lakewood and Passaic, New Jersey, and Monsey, New York, one can hear just above a whisper: We need to get a gun.

Even those who won’t actually get a gun license or ever shoot a pistol—Jewish urbanites, the high-rise dwellers of the Upper West Side of Manhattan, Miami Beach, or Lincolnwood, Illinois—feel somehow, somewhere in that (often disavowed) place where human aggression resides: I’d sure like to feel the cool comfort of a 9 mm Glock right now. Some have even advocated for a new Jewish armed-defense organization.

All this talk reminds me of a lesson I learned in high school in the late 1970s. At that time, the Jewish Defense League was ascendant, along with its slogan: “Never Again.” The group’s logo is still instantly recognizable: a meaty, masculine fist against a background of the Star of David.

The JDL was founded by Rabbi Meir Kahane in 1968 and its stated goal was to protect Jews from all forms of antisemitism “by whatever means necessary.” The idea was that never again would we, the Jews, go like sheep to the slaughter; never again would we be the wards of the world, displaced, defenseless, vulnerable to the whims and the caprices of sinister or indifferent world powers.

The JDL was initially seen as a godsend at a time of crisis for Jews in the urban enclaves of Crown Heights, East Flatbush, and Far Rockaway in New York; Boyle Heights and Fairfax in Los Angeles; Skokie, outside Chicago; and other areas where, in Martin Luther King’s phrase, “a marvelous new militancy” had taken hold among other ethnic groups as well. This militancy pitted Jews and other minorities against each other.

The JDL gave Jews like my father, a rabbi and school principal, a new backbone. Now we Jews did not have to run away from “our” neighborhoods as we once did from the Bronx and Brownsville. The JDL was on hand to patrol the streets, escort children to yeshiva, and watch over the barrios and old men in the urban haunts who would (still) go to shul morning, noon, and night. Yet over time, the JDL branched out into more “ambitious” vigilantism and was linked to a firebombing of the office of the impresario Sol Hurock in 1972 and various assassinations and murder attempts of those they deemed to be “enemies of the Jewish people.”

For us young kids at Yeshiva Chaim Berlin, it was a little different. The JDL initially made my classmates and me proud. We were not the young men of our parents’ and grandparents’ generations. We were strong. We would know not just the power of prayer and study, but also the feel of an M-16; we would know how to fix a tank, place high explosives under a bridge and fly an F-16 fighter jet. Jews would take up arms in their own cause. We would fight back.

There was only one thing that stood in the way of our somewhat grandiose thinking: our rebbe. He wasn’t just any rebbe. He was Reb Chaim Segal, a Holocaust survivor, a majestic man of great passion and learning who hailed from prewar Poland—a town called Ostrov.

When he heard us espouse the JDL slogan, he would erupt in rage: “Never Again, Never Again, you say? Vere you dere?” he would ask in his heavy Yiddish-English. “I was dere. Zey zaynen arayngefallen—they invaded my hometown, rounded up the Jews, and I escaped with my life. I saw my father die. How many Nazis have you met? So don’t talk.”

Obviously, there was a surplus of intensity to his reaction and it was never clear to us why mention of the JDL (which, on the surface, was based on the sound idea of self-preservation and self-reliance) evoked such an emotional response in him. After all, in other quarters, we might have been lauded, even celebrated, but not at Yeshiva Chaim Berlin and not with Reb Chaim Segal. He would hear none of it.

Reb Chaim was not saying that resistance was not kosher. He well knew that the greatest sages had participated in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Rather, he was against placing “resistance”—even in the name of self-defense—at the center of the Jewish story. According to his thinking, a Jew holds two heroisms: the heroism of the battlefield and the heroism of belief through a strenuous search for God through the study of His word and at the same time, a brave resistance to the temptations of a hedonistic world. If you glorified the gun over the Torah, he was not the rebbe for you.

“I don’t teach hooligans,” he said as a matter of policy. To those who did not heed, he said, “I am not your teacher and you are not my students. Get out.” He sent some of us packing once when we took the law into our own hands against an antisemitic group from a local public high school. Within a few days, most of us made up with him, but one, a staunch JDL’nik, refused to reconcile with Reb Chaim, and to that boy he simply never spoke again.

Reb Chaim was a man who inspired fear as well as love—with such a man one had felt a holy brutality—but intuitively, I felt something of his wisdom even when I was 15, yet I never fully understood his reaction. Until now.

He was not against the JDL for the usual reasons: a peculiar Jewish penchant for fatalism, or a bourgeois, middle-class aversion to violence. Rather, his primary understanding of Jewish life was conditioned by his belief in God. It’s not that he believed in passivity as a passageway to holiness, but for Reb Chaim, the point for a Jew was to find God in whatever the circumstances.

To take up arms in the way of the JDL was to assert a lie: that we are masters in our own house. That a “greed” for physical survival has overtaken the Jewish essence. That is, to move away from the spirit of God and engage in the human fantasy of omniscience and the folly of omnipotence: We know what’s best and we know exactly what needs to be done and how.

To be sure, in my field of psychotherapy, we know that traumatized people may embark on an extreme program to be physically or financially strong, or whatever the case may be. They promise themselves: I will never be vulnerable again to this or that threat. This “promise” may provide a temporary buoyancy, but it is based on a central fantasy, the idea that one can control one’s fate. We sometimes can, but not always.

Ghetto Fighters’ House Archive

On Oct. 7, Jews were slaughtered in an open field, like in my grandfather’s time on the steppes of the Pripyat Marsh and across the plains of Isaac Babel’s Ukraine, by the wild Cossacks of Gogol’s Taras Bulba where the Jews were tossed en masse into the River Dniester.

In the face of this, one may be tempted to retreat into the understandable fantasy of a one-dimensional ethos of Jewish self-defense. God was never to be found in a singular system or posture, but rather in a restless uncertainty—a restless confidence in encounters with an ever-elusive divinity that doesn’t preclude taking up arms, but shuns it as a way of life. Reb Chaim turned out to be quite prescient, as within a short time the JDL faded into its now-famous fanatical and self-destructive extremism.

To reinforce his point, Reb Chaim told a story in the name of his rebbe—the rosh hayeshiva, Rav Yitschok Hutner—a tale from Warsaw of the late 1800s: The young Jewish men of the city had learned that a local official was inciting a pogrom against them. They turned to the rebbe of Ger and asked him how to deal with the threat. “Don’t worry,” he told them. “God will take care.”

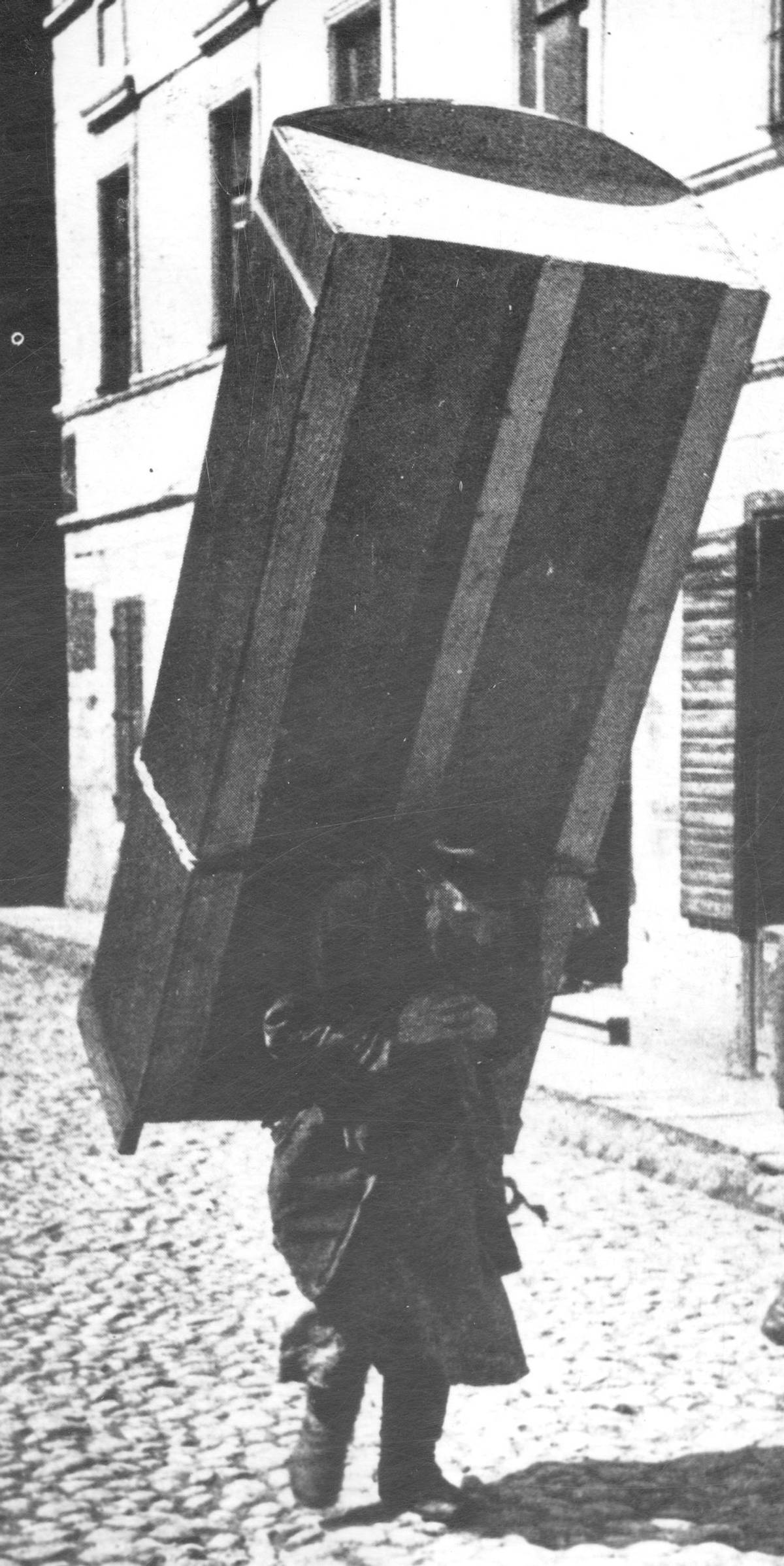

The strongest Jewish men in Warsaw at the time (as recounted by the late Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik and others) were the porters who carried everything, including pianos, on their backs. The rebbe, of course, knew this, too, and summoned the chief porter.

The porter told the rebbe. “Nothing to worry about.”

The next day, the inciter mysteriously “disappeared.”

Later that week, on Friday when the rebbe went to the mikvah, he took a different route down the street where the porters hung out. He gave them the Hasidic equivalent of a fist bump and blessed them.

Reb Chaim told the story with a smirk: Nothing wrong to take out a hit on a guy who wants to kill Jews, but spare me the false heroics of JDL’s “never again.” To kill the killer is a mitzvah, but then return to the business of being a Jew.

It is likely, too, that Reb Chaim would have endorsed our getting a gun in these fraught times—but he may have cautioned us to do so without the hauteur of omniscience and omnipotence. To use a psychoanalytic phrase, we mustn’t flatter ourselves. The ego is not in charge.

If I understood Reb Chaim correctly, it is not the gun, then, that is objectionable, but the arrogance of assuming a gun will fix the problem and confer protection. It may protect the “body” of the Jewish people at times, but the soul of the Jewish people lies elsewhere and needs a different form of protection and cultivation.

On his deathbed, Reb Chaim’s last words to one of his talmidim, his students, were “banim atem lashem”—you are all the sons of God. As if to say, we are mere sons of God. There is a world, there is God, and we do everything we humanly can. We act with force as though we are in charge of our own destiny, even as we must know that we are not.

Alter Yisrael Shimon Feuerman, a psychotherapist in New Jersey, is director of The New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies. He is also author of the Yiddish novel Yankel and Leah.