Judaism During—and After—the Pandemic

Social distancing has, in a way, allowed us into each other’s homes more than ever. Will being apart end up bringing Jews together?

The coronavirus crisis has turned our world upside down. It has confined us to our houses, separated us from our loved ones, and isolated us from one another. But could it also be bringing us closer together?

In the social media world of the 21st century, we spend a fair amount of time crafting an image. The clothes you wear, your makeup and hairstyle, the articles and pictures that you share online are all part of a persona that you project out into the world. They reflect what you want the world to see, know, and think about you. It’s a natural thing that we do, and it’s usually not conscious. We simply want to put our best face forward. Plus, there are social norms around how we will look and behave in public—whether at work, at the store, or at the theater.

The same is true in our Jewish lives. When you go to shul (even in relatively informal, down-to-earth congregations such as my own), you choose your clothing, adjust your smile, and enter the synagogue to be with others who have made similar choices. Your fellow congregants get a public version of you. That means that most of our Jewish experiences take place behind a façade of sorts—naturally, since the rest of the world doesn’t come into your house with you.

Until now.

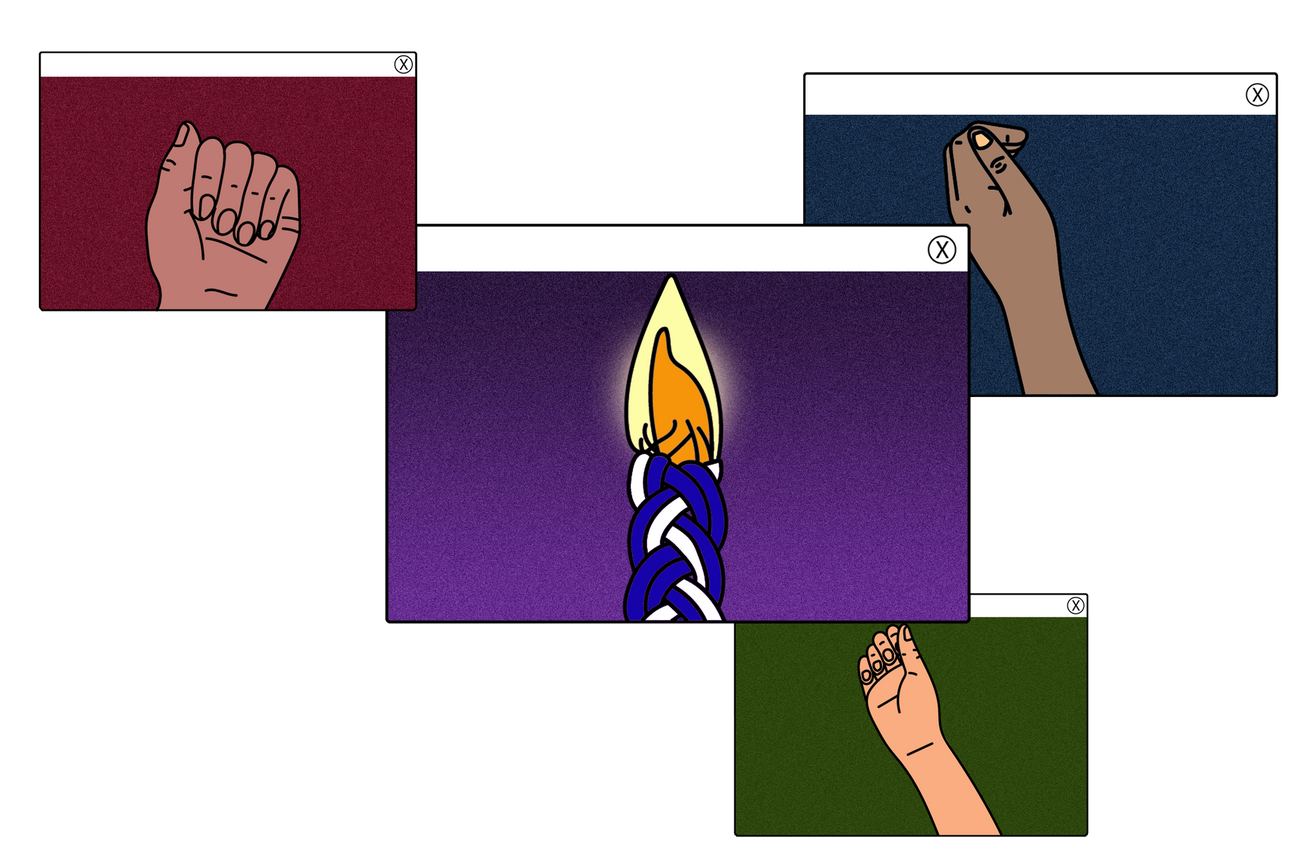

The irony of social distancing is that in some ways, we are seeing more of each other than ever. Technology has allowed us to organize meetings, reunions, happy hours, and Passover Seders—sometimes with people we wouldn’t have seen otherwise. My congregation, like many synagogues, has moved our services and programs online, and they are bursting at the seams. Apparently lots of people want to join in Havdalah, or study Talmud, when they don’t have to change out of their pajamas to do it!

Which leads me to my point. All of a sudden we are being let into each other’s homes in a way that we never were before.

On a recent Saturday night, I was participating in a communal Zoom Havdalah—nearly 100 members of the congregation gathered (virtually) to bid farewell to Shabbat—when my 11-year-old son passed behind me with his toy light saber. A congregant texted me lightheartedly: “I think I just saw a Jedi walk through your living room.”

During Wednesday morning Talmud class, in the midst of a spirited discussion, a woman’s 6-year-old daughter wandered in, plopped down on her mother’s lap, and kissed her on the cheek.

One of our regular Torah study participants spent the first three weeks of social distancing refusing to turn on her camera. (“You don’t want to see me first thing in the morning.”) This Shabbat, she reversed course (“We’re all going to need a haircut and a color when this is over anyway”) and allowed us to see her reading the text from her sofa.

These are only a few of the extraordinarily personal and lovable experiences of the past few weeks. There are more: a shiva minyan with loved ones from around the world; a Passover Seder where 75 families sat around their own dining room tables and led each other in blessings, to the sound of their dogs barking in the background. As a rabbi, these weeks have been extraordinary. I have had the rare privilege of seeing my congregants in their natural habitat—on their couches, at their tables, surrounded by their families—and of letting them see me in mine as well. We are seeing, and allowing others to see, something of our real selves.

There is precedent for this phenomenon in Jewish text. In Chapter 33 of Exodus (which we read during festivals) Moses asks to see God’s face—asks for the comfort of God’s presence. The answer, famously, is that Moses can only see God’s back, because “no one may see My face and live.” In other words, according to this passage, even God is engaged in social distancing—has put up a façade to block Moses from seeing Her true essence. This is present in our sacred text because it is an expression of something deeply human: an impulse to hide and protect that we experience every day.

But what happens when we do let one another see our faces? What happens when our communal Jewish experiences take place not in the public square, but in our own homes, surrounded by our messy kitchens and our favorite artwork, flanked by our energetic children and our hairy, shirtless husbands (like the one who wandered by during a congregational Havdalah—no, I’m not making that up)?

We are getting a taste of that right now. And it might just change everything about being Jewish.

Certainly, we wouldn’t choose this pandemic. But since we’re stuck in it, it’s worth noting that something is changing about the way we relate to each other. And it is something that doesn’t have to end when social distancing ends. Imagine the closeness we are building, the connections that we are forging when we let each other into our homes. Imagine if we could harness that kind of thinking once the coronavirus is vanquished—allowing our guard to drop just a bit in the synagogue; inviting one another into our homes; organizing our community programming around the building and strengthening of relationships. Working to ensure that Jewish settings are safe spaces, where it is OK to be human, where we relish one another’s uniqueness, warts and all. A little more real and a little less façade; a little more “face” and a little less “back.”

That is the mixed blessing of this unique moment. Even in our distancing, it represents an opportunity to focus on the ways that we can support each other, know each other, and invite each other in.

The daily morning service opens with these words: “Mah tovu ohalecha Ya’akov, mish’kenotecha Yisrael—How lovely are your dwelling places, O people of Israel.” They really are lovely. And so are we. Welcome home.

Micah Streiffer is a rabbi, writer, musician and teacher based in Toronto. He serves as spiritual leader of Kol Ami Congregation in Thornhill, Ontario, and is the host of the weekly 'Seven Minute Torah' podcast.