Viewers of King Charles III’s recent coronation and consumers of Netflix’s The Crown notwithstanding, Americans have a history of hating on kings. As burgers are grilled and beers raised at barbecues this July 4, liberty-loving Americans will, of course, be celebrating the Revolutionaries who declared independence from England’s George III. As the Founding Fathers put it, “The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.” Yet few of these full-bellied fans of freedom are aware that an ancient biblical king actually helped inspire the colonists in their fight for independence from England.

Seeking reassurance that their rebellion against the British was in line with God’s wishes, colonial ministers sought a model of military might and spiritual standing. They found it in the figure 1 Samuel 13:14 calls “a man after God’s own heart”: David.

As James P. Byrd notes in his Sacred Scripture, Sacred War, Congress issued a May 26, 1779, statement to inspire its weary citizens amid the harshness of ongoing battles. It invoked the young shepherd boy David’s slingshot-powered defeat of the sword-wielding Philistine giant Goliath.

America, without arms, ammunition, discipline, revenue, government, or ally, almost totally striped of commerce, and in the weakness of youth, as it were with a “staff and sling” only, dared in the name of the Lord of Hosts to engage a gigantic adversary, prepared at all points, boasting of his strength, and of whom even mighty warriors “were greatly afraid.”

Hoping that providence would guide their hand against the mighty and arrogant British troops as it had David’s makeshift weapon against an overpowering foe, Congress saw in the American cause a similarly righteous struggle that, they prayed, might merit a miraculous victory.

This wasn’t the first time David had been cited in support of the colonists. John Witherspoon, who taught James Madison and served as president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), had wondered, in a 1776 sermon: “Has not the boasted discipline of regular and veteran soldiers been turned into confusion and dismay before the new and maiden courage of freemen in defense of their property and right?”

The Book of Psalms, traditionally attributed to David, had an “overwhelming” popularity in Revolutionary America, Byrd notes. Wartime preachers cited this book from the Hebrew Bible five times more often than the New Testament’s Book of Revelation, with no message more timely than David’s poetic proclamation in Psalm 144 that God taught his “fingers to fight.”

Ironically, a couple of decades prior to the Revolution, David’s speech against Goliath as they readied for battle had been used to inspire Native Americans fighting alongside the British against French troops. Hyping up for the heat of battle like Rocky heading to the ring to the chords of “Eye of the Tiger,” Jonathan Edwards—whose famous father of the same name had sermonized about “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”—spoke of a slingshot in the hands of a simple shepherd. Speaking in 1755 from his frontier post in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, he addressed a primarily Native American congregation by recalling David’s verbal shot across the bow: “Thou comest to me with a sword, and with a spear, and with a javelin; but I come to thee in the name of the Lord of Hosts, the God of the armies of Israel, whom thou hast taunted” (1 Samuel 17:45).

Adopting David as a biblical forebear of the colonists’ rebellion was no simple matter, however. The Bible itself recounts young David’s hesitancy to harm King Saul. Thus in 1759, with the popular George II on the throne, preachers cited David’s hesitancy to hurt the monarch as a means of discouraging rebellion.

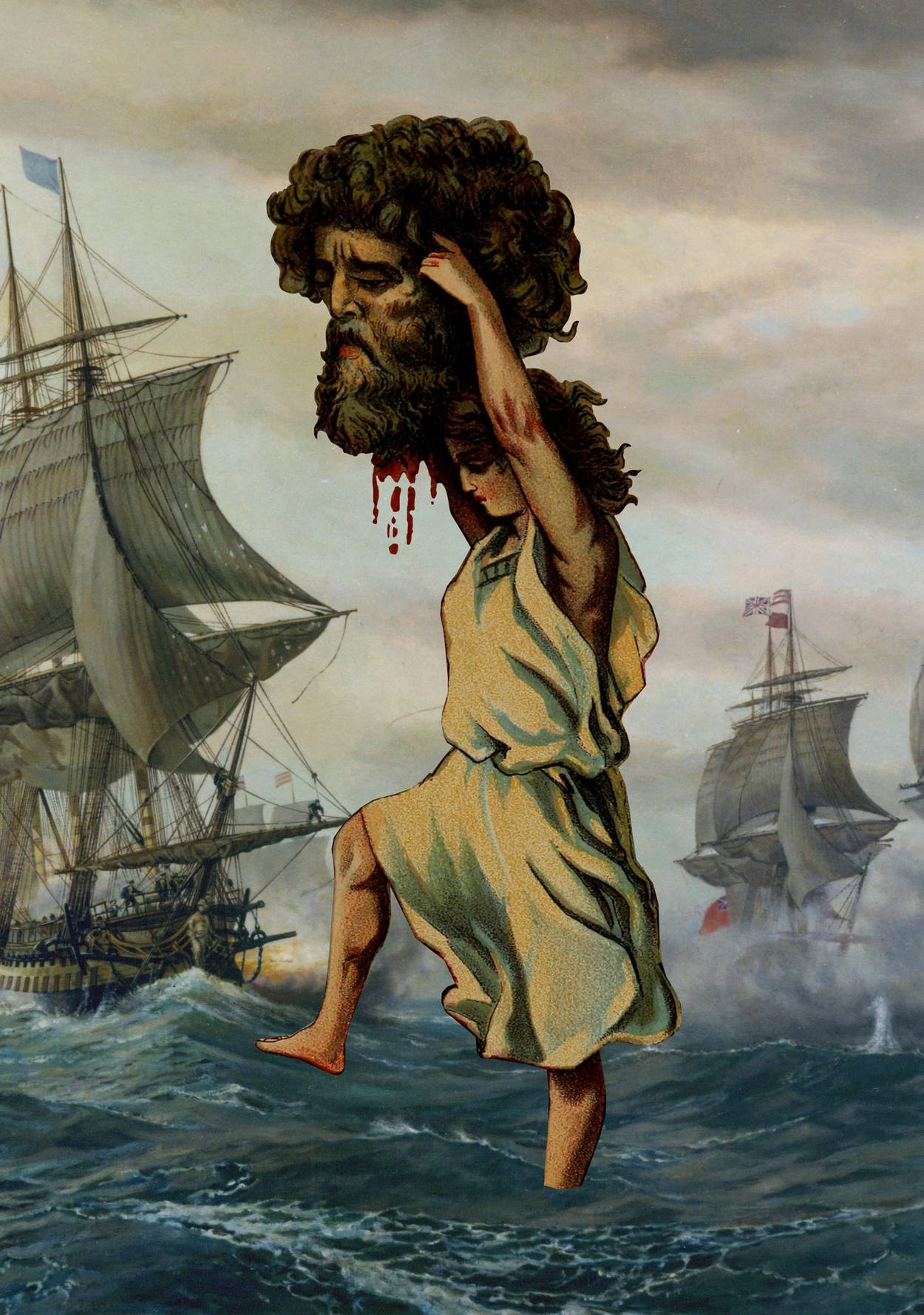

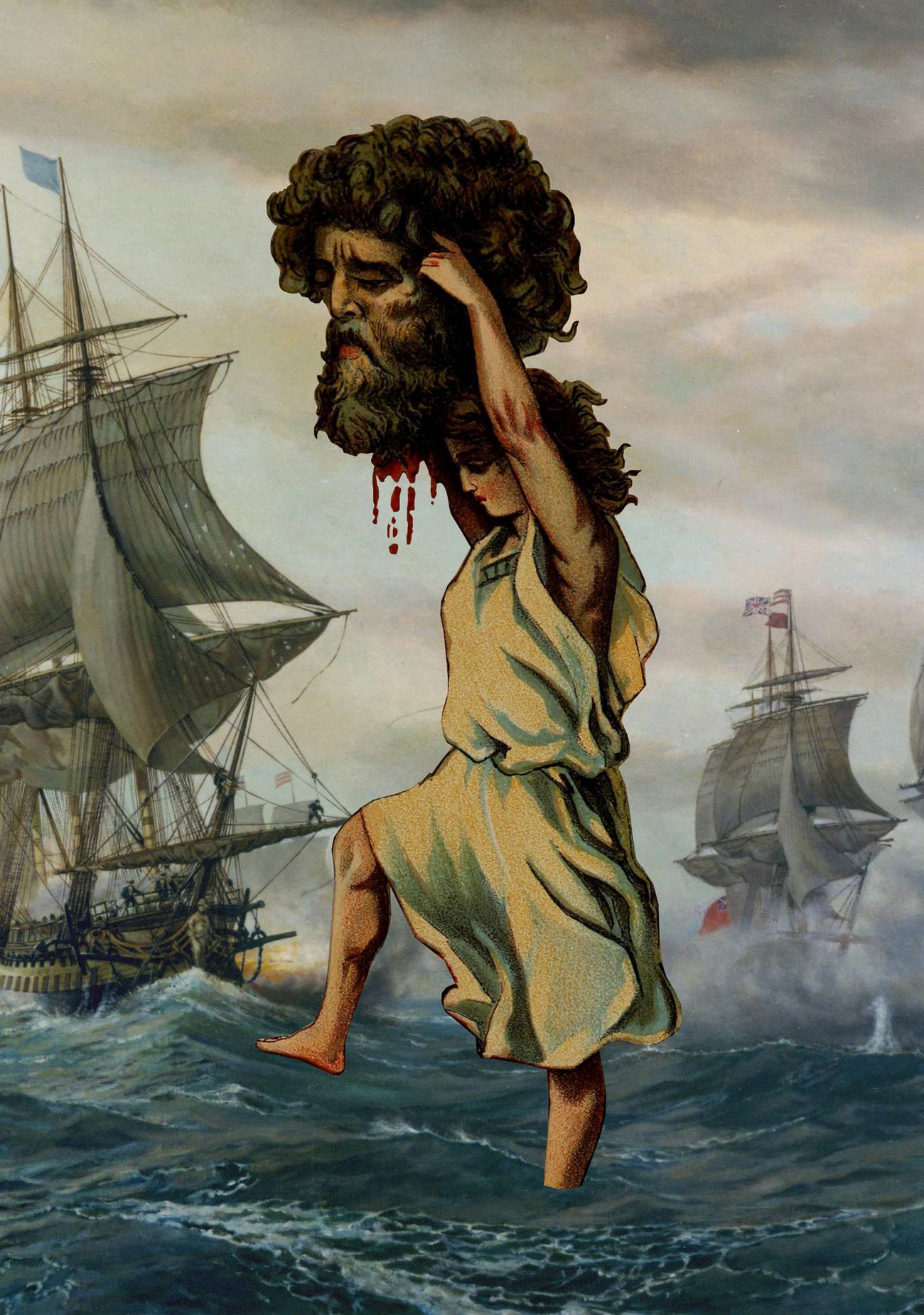

Seeing in the subsequent pre-Revolutionary stirrings against the later George III a similarity to Absalom’s perceiving his father, the elderly King David, as a weak and ineffective ruler, Faith Robinson Trumbull of Lebanon, Connecticut, embroidered her feelings on the current state of affairs. She and her husband, Governor Jonathan Trumbull, were deeply committed to the rebel cause. Faith’s work, “The Hanging of Absalom,” crafted in 1770, depicted David’s son’s thick hair ensnared in the branches of a tree, leaving him hanging and defenseless against attack, as recounted in 2 Samuel 18. Indicting George III through with her needle, Trumbull was arguing that England’s irresponsible rule was subjecting the colonists to similar harm.

Once the war began, however, emphasis was placed on David as a positive figure of spiritual and strategic skill, and it was another offspring of the Davidic line who was seen as paralleling the tyrannical British monarch. A sermon by Peter Whitney on Sept. 12, 1776, evoked the story of Rehoboam, the son of, and successor to, David’s son Solomon. Just like Rehoboam in 1 Kings 12, Whitney railed, George III rejected “the counsel of the old men, and followed the impolitic advice of his young mates.” Alluding to the revolt that resulted from Rehoboam’s oppressive policies, Whitney preached, “We need not wonder that the 10 tribes of Israel fall off from the house of David” as a result of the abandonment of the “righteous governance for which God had long blessed them.”

Across the pond, English preachers understood their own Goliath-like role in the war. In 1776, the British Methodist John Fletcher warned that while the Americans might be wrongheaded Davids, they were Davids nonetheless. The Americans, Fletcher wrote, were “fasting and praying,” as they hoped for divinely granted victory, while the British were “ridiculing” the American as “fanatics, and scoffing at religion” while “running wild after pleasure.” Prophetically predicting the unexpected colonial victory, Fletcher warned:

If the Colonists throng the houses of God, while we throng playhouses, or houses of ill fame; if they crowd their communion tables, while we crowd the gaming table … if they pray, while we curse; if they fast, while we get drunk…If they shelter under the protection of heaven, while our chief attention is turned to our hired troops; we are in danger—in great danger ... A youth that believes and prays as David, is a match for a giant that swaggers and curses as Goliath.

Decades after the Revolution’s success, the cause of a righteous fight for the spirit of America was claimed by both the North and South in the American Civil War. It is no surprise that each sought to bear the mantle of David. After all, as President Lincoln noted in his second inaugural address, the two sides “read the same Bible and pray to the same God.”

As Byrd documents in A Holy Baptism of Fire and Blood, following the defeat of the North at the Battle of Second Manassas over Aug. 28-30, 1862, the North Carolinian Presbyterian minister Joseph Atkinson saw Stonewall Jackson as a modern-day slingshotter. “When we come to our own day,” he preached, “may we not hope that Jackson, the Christian hero, the man of piety and prayer, with a fervency of spirit, like David’s in the sanctuary, and a martial order like David’s in the field, has been graciously given us as the interpreter and impersonation of the Christian element and the Christian consciousness of this grand conflict?”

The North, in turn, saw in Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, as Absalom, whose rebellion, unlike in Trumbull’s earlier rendering, was now deemed illegitimate. The Boston-based Baptist minister Daniel Eddy captured the tragic, but necessary, defeat of Absalom by his father’s troops as a model for the North’s motivations.

There can be no glory in this war, however it may result, and whatever brilliant deeds may be done … Our great nation at its close will weep as David did over Absalom … it is our own blood that is flowing … The last we see of Absalom, the traitor and the usurper, he is hanging on an oak … so perish all traitors, and for the good of the country, and the honor of humanity, and the glory of God, the sooner they perish the better!

The Northern Presbyterian George Duffield echoed the sentiment, decrying “the rebellion of the proud, luxurious, lascivious, unprincipled, murderous Absalom, against his noble, unsuspecting, too affectionate, and overindulgent father, David.”

A Vermont minister inspired by Lincoln’s call for volunteers following the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter saw the coming battles as mirroring those fought by David’s forces. Citing the words of Joab, David’s commander, in 2 Samuel 10:12, he expressed his wish that the North would “be of good courage.” “Let us play the men for our people,” he thundered, “and for the cities of our God.”

Joseph Gillespie, a friend of President Lincoln’s, recalled the president offering a hand of mercy and forgiveness to the South in a similar spirit. “Well,” Gillespie recounts Lincoln musing, “some think their heads ought to come off; but there are too many of them for that, and for one, I would not know where to draw the line between those whose heads (it might be said) ought to come off or stay on.”

“My policy would be different,” Lincoln continued. “I would prefer to follow the example of King David. I have been recently reading the history of the Rebellion of Absalom, and would be inclined to adopt the views of David. When David was fleeing from Jerusalem, Shimei cursed him. After the rebellion was put down Shimei craved a pardon. Abishai, David’s nephew, the son of Zeruiah, David’s sister, said, ‘this man ought not to be pardoned, because he cursed the Lords ‘anointed.’ David said, ‘What have I to do with you, ye sons of Zeruiah, that you should this day be adversaries unto me? Know ye that not a man shall be put to death in Israel.’”

A slayer of giants whose faith stirred generals to battle, a prophet whose words powered patriots, a monarch who inspired mercy, David has long served as the shepherd of Americans’ courage that, against all odds, God would grant us victory. And that is another reason to celebrate today, amid the burgers and beers.