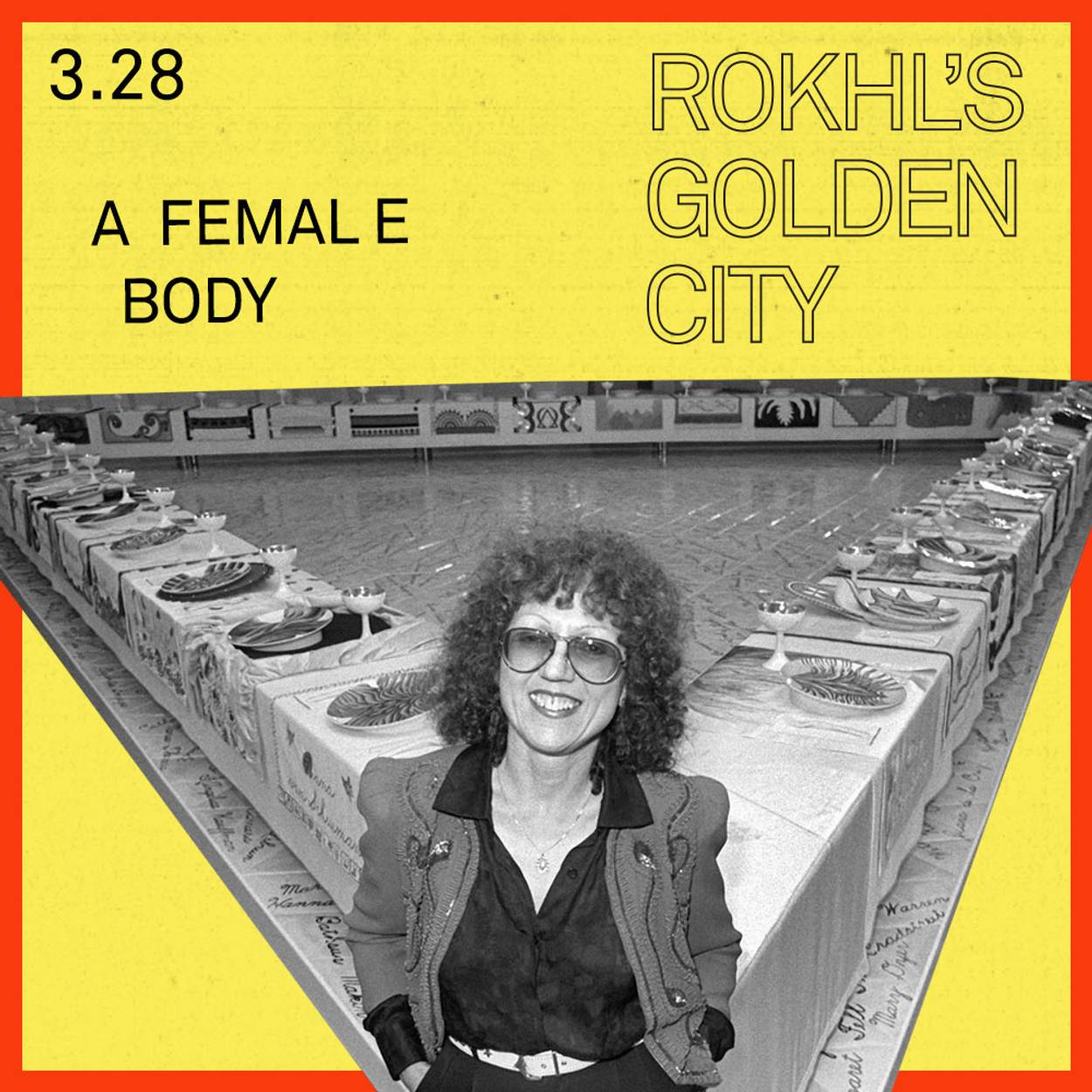

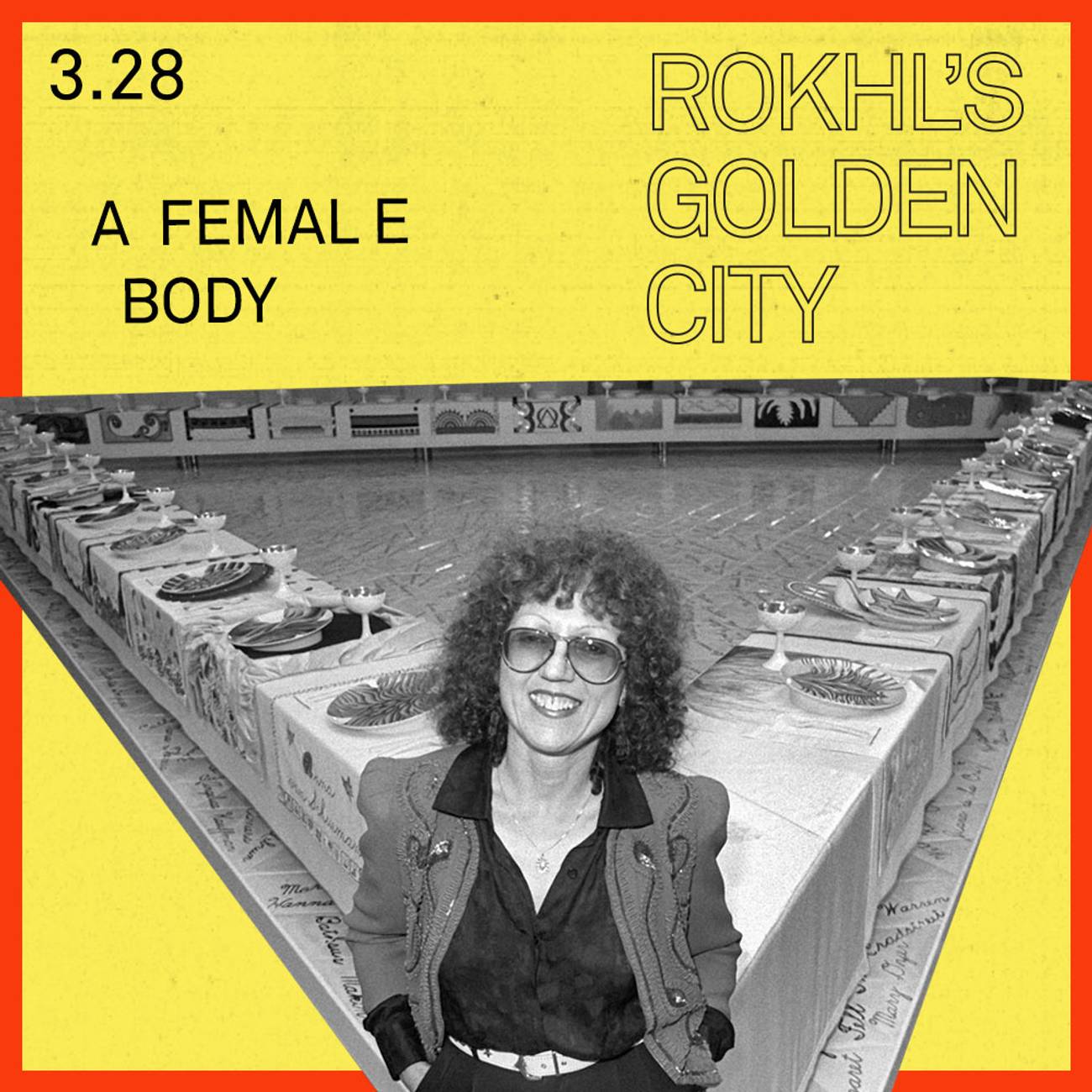

Women’s History Month is almost over, but I am still enjoying a bit of the afterglow of a truly special, dare I say spiritual, experience. After months of planning to go “next week,” I finally saw the Judy Chicago retrospective, Herstory, on its very last day at the New Museum in New York City.

The exhibit sold itself as the first comprehensive New York survey of her 60-year career, and I was beyond excited. When the Brooklyn Museum acquired Chicago’s most famous work, a massive installation called “The Dinner Party,” in 2007, I made a joyous pilgrimage to see it with a beloved group of girlfriends.

This time, however, I ended up going solo. At one point in early February, I suggested it as a possible outing with a new friend of mine who was in town for a few days. As excited as I was to see the exhibit, I found myself faltering a bit in the proposal. This friend, S., is warm and bubbly and we can talk for hours about Orthodox feminism or Jewish witches. She also happens to be trans.

The feminism of 2024, my feminism, is necessarily trans-inclusive, and therefore has an uneasy relationship with the biological essentialism that colors so much of second-wave feminist art and activism. I don’t think the biological focus of a work like “The Dinner Party” is necessarily transphobic, however, and I was relieved that S. turned out to feel the same, even though a trip to the New Museum ultimately wasn’t in the cards for us.

For me, Judy Chicago’s work is tied up with a warm, cherished nostalgia for my undergraduate days and my entry into the wild world of feminist art and art history. It was the 1990s and the pop feminist zeitgeist of my generation—Riot Grrrl and Lilith Fair—had left me cold. But in art history class, I found my real sweet spot, reading foundational feminist art history of the 1970s. Learning how women artists had been (often violently) suppressed historically, and how they were still excluded today systematically, Chicago’s “Dinner Party” had an air of inevitability about it. In the piece, Chicago gathered 39 female artists, mystics, leaders, and legends from history and created a banquet for them. Each woman’s place setting features exquisite variations on explicitly “vulvar forms.” Indeed, a great deal of Chicago’s work returns to the mystical-biological-feminine and a search for female lineages.

The New Museum retrospective was a journey through a lifetime’s work, of which “The Dinner Party” is only one of many highlights. In the 1960s, Chicago went to auto body school to learn specialized painting techniques, resulting in a series of painted car hoods. She then learned how to work with pyrotechnics. Each gallery section brought some fresh revelation of technical mastery or emotional concern.

For me, some phases were more successful than others. I was especially conflicted by Chicago’s exploration of Holocaust themes, executed with her husband and collaborator, Donald Woodman. I longed to see a more explicit exploration of Jewish identity in her work that didn’t circle back to trauma. (Though I loved finding the one bit of Yiddish in the show in one of her luminous stained-glass Holocaust pieces.)

Jewishness seemed to be thick in the subtext of her work, and many of her collaborators in the 1960s and ’70s were Jewish women—including her “Womanhouse” co-creator, feminist craft icon Miriam Schapiro. But that subtext really came to the surface in the full floor gallery organized around the theme “City of Ladies.” There, work by almost 90 artists was brought together, creating Chicago’s own “alternative canon.” It was an indescribable joy to wander through, here, finding a handwritten draft of a poem by Emily Dickinson, and there, an oil painting by none other than Artemisia Gentileschi.

I was moved almost to tears by a humble fabric swatch book created by Otti Berger. In the 1930s, Berger had a textile studio in Berlin, where her innovations “included sound-absorbing, light-reflecting, and water- and tear-resistant technologies.” In 1938, Berger left the safety of London to return to her hometown, in what was then Hungary, to care for her sick mother. Denied a visa to the United States, Berger was murdered with her family in Auschwitz.

I could have spent hours wandering the “City of Ladies” gallery, lingering among the extravagant and diverse representation of Jewish women among Chicago’s personal canon: the avant-garde film of Maya Deren, an oil painting by Florine Stettheimer, a minimalist matzo cover created by acclaimed artist-weaver Anni Albers.

I’ll admit I’m perhaps too invested to critique the show properly, or I identify too closely with Chicago as a giant of my own chosen lineage of Jewish women artists. But I was surprised when one review of the show was put off by its claims for the importance of Chicago’s work (isn’t that what a retrospective is all about?) and deemed it “insensitive and disrespectful” for placing gender-queer artists such as Claude Cahun and Gluck (who were clearly identified as gender-queer) “under the umbrella of ‘Ladies.’”

The reviewer seemed unaware that the “City of Ladies” theme has been a favorite of Chicago’s for quite a while, and carries deep thematic connections to her work. The title is a reference to an early 15th-century French work, The Book of the City of Ladies by Christine de Pizan. De Pizan’s Book is a polemic in defense of women; a literary city populated by notable women of history and legend, such as Mary Magdalene, Sappho, Esther, and Judith. These virtuous women are meant to counter misogynist slanders of the time, and are assembled by our narrator, Christine, who is first and foremost a reader and a lover of books. Reading, however, has brought about the medieval version of an existential crisis. For everywhere she looks, male authors are decrying the base and wicked nature of women. If these men are to be believed, women are “the vessel as well as the refuge and abode of every evil and vice.” Christine cries out to God at her misfortune, saying that “I considered myself most unfortunate because God had made me inhabit a female body in this world.”

Reading Christine’s lament, one cannot help but hear echoes of the traditional Jewish (man’s) prayer of thanksgiving, recited upon awakening: “Blessed are you, Lord, our God, ruler of the universe who has not created me a woman.” A parallel blessing exists to be recited by women, thanking He “who has created me according to his will.” Interestingly, this alternative women’s prayer is first cited by a liturgical authority in the 14th century, right around the time that Christine was having her crisis.

The Book of the City of Ladies uses this gallery of assembled “Ladies” to make a radical argument for the inherent goodness of women, and for their education and participation in civic life to be on the same level as men’s. But neither Christine, the narrator, nor Christine de Pizan, the author, is interested in revolution. Many of the qualities she sees in the idealized female residents of her City are the qualities already prized in women by European Christian society of that time, such as chastity and devotion to family.

In any case, an argument, no matter how radical it is, is still an argument. Without a plan for collective action, or systemic reform, the beautiful City of Ladies would remain nothing more than allegory. Which raises the question of how those who are disenfranchised or otherwise oppressed can achieve reform from within a system.

As I write this column, Women’s History Month in New York City is closing out with yet another agune (so-called “chained women”) scandal roiling various Jewish communities. Hundreds of years later and worlds away from medieval Christian Europe, the modern Jewish women fighting on behalf of agunes are, much in the spirit of Christine de Pizan, grappling with the problem of fighting systemic misogyny from inside the system. Their plan of action, however, differs quite radically.

Agunes are women whose husbands refuse to grant them a divorce according to Jewish law. They are thus unable to remarry, leaving them in a nightmarish limbo, potentially for the rest of their lives. Various forms of coercion have emerged in response to the agune crisis, including, but not limited to, extrajudicial violence and bribery of the recalcitrant husbands. The problem is that those with the power to systematically eliminate the problem, the rabbis, have consistently chosen not to take action to protect agunes. Indeed, when an activist named Adina Sash, aka Flatbush Girl, called for a “sex strike” recently on behalf of one particular agune, highly esteemed rabbinical leaders immediately leapt into action—to clutch their pearls and condemn the still theoretical action.

As an outsider reading some of the many tragic stories of modern agunes, it’s hard not to see women in ultra-Orthodox and Haredi communities as tragically oppressed victims, especially when callous condemnation, and the zealous protection of male privilege, tends to be the official response to their ongoing suffering.

In stark contrast to the agune controversy once again making news, Jessica Roda’s new book, For Women and Girls Only: Reshaping Jewish Orthodoxy Through the Arts in the Digital Age, brings our attention to a completely different way of understanding the agency of women within ultra-Orthodox communities. Roda is an ethnomusicologist who has spent the last few years immersed in various ultra-Orthodox communities in North America, studying the role of music and arts in women’s lives. (Here I am using “ultra-Orthodox,” as it is Roda’s terminology in the book.)

Jewish law, as interpreted by modern ultra-Orthodox communities, demands that Jewish women be private and modest in their appearance—that is, tsnius. In many instances, stringencies have grown to the point that the norm now dictates that women’s faces cannot be shown in frum publications. The voices of women and girls are considered especially dangerous, and men outside of the immediate family are forbidden from hearing a woman (or girl) sing, a principle known by the shorthand of kol isha. Such communal norms would seem to drastically minimize women’s participation in communal discourse. That analysis, however, misses the parallel world that exists “for women and girls only,” the label appended to frum women’s media, warning men away from consuming forbidden content.

Roda details how the advent of accessible digital tools and platforms created new opportunities for frum women to be seen and heard, and how the exigencies of the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated that process. One of the astounding revelations of Roda’s book is that it is now possible for a frum female “celebrity” to exist within a world that so severely delimits how and when Jewish women can be seen at all. Moreover, for many of the women, making music “for women and girls” has engendered a quiet rebellion against rabbinic authority.

“Over the course of my ethnographic research,” Roda writes, “I saw many women disregard religious authority in making decisions about their creative projects, or search for an ‘open-minded,’ ‘liberal’ rabbi to validate their choices …” Though these women followed the strict standards for modest presentation, they “did not request rabbinical permission to initiate new practices such as founding a musical band, building a home studio for recording or teaching … producing music videos, or participating in social media campaigns to advocate for changes for the sake of ‘female empowerment.’”

Strict sex segregation is an important facet of ultra-Orthodox life. Girls are educated in their own schools and camps. In those spaces, women and girls have free(-ish) reign to express themselves creatively, to and for each other. As Roda writes, “ultra-Orthodox girls have always engaged in the arts in gender-segregated spaces; that phenomenon is not new. What is new, however, is the transformation of the arts from educational, religious, and collective purposes to economic, social, and individual ones, including the birth of the ‘frum female artist.’”

These new purposes take on a number of different forms. There is an informal market, where women produce music for each other in a nonprofessional capacity. Even nonprofessional female artists can now record in home studios owned and operated as businesses by other frum women. They can then distribute those songs via novel channels such as WhatsApp groups, unlisted YouTube videos, and dedicated phone lines. The music made by women in this informal market is not distributed through traditional commercial networks or oriented around stars and individual artists. It travels with them along preexisting networks, reinforcing their collective identity as creators, but also as Jews. This new digitally enabled activity heightens their understanding of “belonging to a transnational community, one that transcends affiliations to specific Hasidic branches, Litvish local communities, or general localities.”

Despite its ostensible segregation from the music made by men, and invisibility to male listeners, the “informal market” of women’s music is very much part of the same media ecosystem. The interplay between the “markets” can be richly layered in dialogue, as much as any niche music scene with quick production times and a looser relationship to copyright.

Roda gives the example of a song performed by Benny Friedman in 2019, “Charasho.” The music video for the song is highly produced and features quite a few musicians from the non-Orthodox klezmer scene in New York City.

A few months after Friedman released the song, “the principal of a Hasidic girls’ high school in Borough Park took the melody and recorded it with her own lyrics,” Roda writes. Now titled “I Accept,” the song “circulated via email, WhatsApp, and some girls’ Hasidic school performances” becoming a hit “among women and girls in schools, summer camps, and dance and gym classes across North America, and even the U.K. and Israel” but unknown to male listeners. The song took a further turn when it was adapted into Yiddish by an older woman in Borough Park. The new lyrics emphasized “resilience and acceptance” and reflected elements of her own life story, becoming “Ich Farshtei,” (I Understand). The song was also recorded in a music studio owned by a frum woman, and “distributed not only via email to schools but also over a phone line for women established by [the author of the Yiddish lyrics].” The song took on yet another layer of meaning when the pandemic erupted a few weeks later.

In addition to this informal market of frum women’s music, there is an “emerging formal market of performances for and by women,” which, Roda writes, is “part of the kosher music and film industry.” The work of these women is distributed by the same professional networks as that of the men. While the women working in the “informal market” do not reveal their full names or faces, those in the “formal market” must, by necessity, be “seen” by their fans. They have been pushing the limits of public visibility, especially since the arrival of the pandemic, but they must also negotiate their own desire for artistic recognition while reinforcing the “kosher,” collective, and complementary (to male, mainstream kosher performers) nature of their work.

Bracha Jaffe is one of the most successful and visible of the frum female “celebrity” artists. Her ability to negotiate the competing demands of modesty and visibility is enhanced by the eagerness of frum nonprofits to utilize stars like her in their own publicity. Here, Jaffe appears in a highly produced fundraising video for Chesed 24/7, an organization that provides services to needy populations. By emphasizing the charitable nature of the song, and using the label “For Women and Girls Only,” the creators reinforce their collective, rather than individual, purpose, while staking out a tsnius corner in YouTube’s dangerously unkosher space.

In her conclusion, Roda considers the long-term impact of these frum female artists: “The women described in this book,” she writes, “exist on the fringes of the normative ultra-Orthodox world. Still, their work has increasingly reached more people within their communities—even among the most conservative circles. By suggesting that these women are reshaping Orthodoxy, I envision the frum female art worlds—marginalized though they are—as affecting many people beyond their own gender group, both within and outside Orthodoxy.”

Change comes about in varied and surprising ways. Christine de Pizan may not have been able to reform the patriarchal attitudes of her day, but her work was important enough, and read enough, that it survived to be assigned to yours truly in a college French class, some 600 years later. And while the problems of patriarchy had not been solved by then, they had at least come a significant distance for the better. Nonetheless, the question of reform versus revolution remains a live one for those directly impacted by systemic inequality. Judy Chicago was revolutionary in the radical act of being seen. Her best-known work made visible the intimate biology of the women whose history she sought to reclaim. For her efforts, neither the Metropolitan, the Whitney, MoMA, nor the Art Institute of Chicago have ever acquired her work.

Artists are not exceptions, Roda concludes, but “significantly reflect and inflect social change, which is the case for the frum female art worlds. The future will show whether the emergence of this world results in broader social change or simply new ways to support the existing system.”

MORE WOMEN’S HISTORY: On the Lower East Side: The exhibition “28 Remarkable Women ... and One Scoundrel,” is at the Museum at Eldridge Street, through May 5 … Traces of a Jewish Artist is a brand new biography which recovers the life and work of artist Rahel Szalit. Szalit was born to a Yiddish-speaking family in Telz, Lithuania, and went on to study art in Berlin. Her career as an illustrator and fine artist was cut short by WWII. She was arrested in the infamous Vel d’Hiv roundup in Paris in 1942, after which much of her work was destroyed. Kerry Wallach’s Szalit biography is 40% off from PSU Press with code WHM24.

ALSO: Yiddish Shmoozers will present “Debora Vogel: The Most Important Jewish Modernist Thinker and Yiddish Poet You Never Heard Of.” April 7, 3-4:30 p.m. (PST) … Toronto’s Committee for Yiddish is offering a range of online Yiddish classes starting in April. More information here … The New York Klezmer Series continues its monthly party on April 9. Master Dance Teacher Steve Weintraub will lead a Tantshoyz with a band including series organizer Aaron Alexander, Jordan Hirsch, and Christina Crowder. Music starts at 8 p.m. Hudson Yards Synagogue, 347 West 34th St., between 8th and 9th avenues … You are invited to observe the 81st anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising at the annual commemoration at der shteyn, the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Plaza, in Manhattan’s Riverside Park. April 19, at 2 p.m. Riverside Park between 83rd and 84th streets … The Yiddish Book Center is accepting applications for its new, yearlong “Yiddish Arts and Culture Initiative for Jewish Communities.” Successful applicants will partner with the YBC and get support “to host a series of events exploring Yiddish culture, fostering a deeper understanding of its relevance to Jewish identity.” YBC is looking to partner with a wide range of community organizations, including synagogues, community centers, libraries, and communal residences. Applications are due May 5. More information here … YIVO just launched a new course with the most apt title (and subject) of 2024, “Is Anything OK?: The History of Jews and Comedy in America.” The course is self-paced and free and features some of the most beloved names in comedy, such as Marc Maron and Judy Gold, as well as beloved personalities of the Yiddish world, such as Michael Wex. More information and register here.