The Magic of Logan

Rediscovering the once-Jewish neighborhood in Philadelphia where my mother grew up

12222My mother’s belongings speak to me, long after her passing—ordinary items like wine-stained holiday table linens, polished brass candlesticks, and a house plant gently coaxed from a single cutting.

But other things do, too—things I discover in garment bags and in boxes of commingled unlabeled photos, scrapbooks with pictures and clippings crumbling and yellow with age. These are mementos from her life in Philadelphia between WWI and WWII, a world she never talked about and I never asked about.

Now, I want to know.

I want to know who she was as Paula Beatriz Wohlfeld, the daughter of a button maker and a bookkeeper, whose grandparents immigrated from Eastern Europe in the late 1880s and by 1915 were among nearly 200,000 Jewish people living in Philadelphia, according to the Jewish Virtual Library of the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise.

I sent her circa-1936 black velvet evening coat to the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection at Drexel University. Director Clare Sauro told me the John Wanamaker label on the ivory rayon lining confirms its provenance: the grand store on Market Street, which in its heyday housed a crystal tearoom, the largest pipe organ in the United States, and a 10-foot bronze eagle stationed in the store’s Grand Court. “In the hierarchy of Philadelphia department stores, Wanamaker was at the top. And [the coat] was what young women were wearing,” she said. “It has a sweetness to it and reminds me of things that Ginger Rogers would wear on screen in those days, at the height of her popularity.”

Sauro surmised it was bought for a special occasion, like a prom.

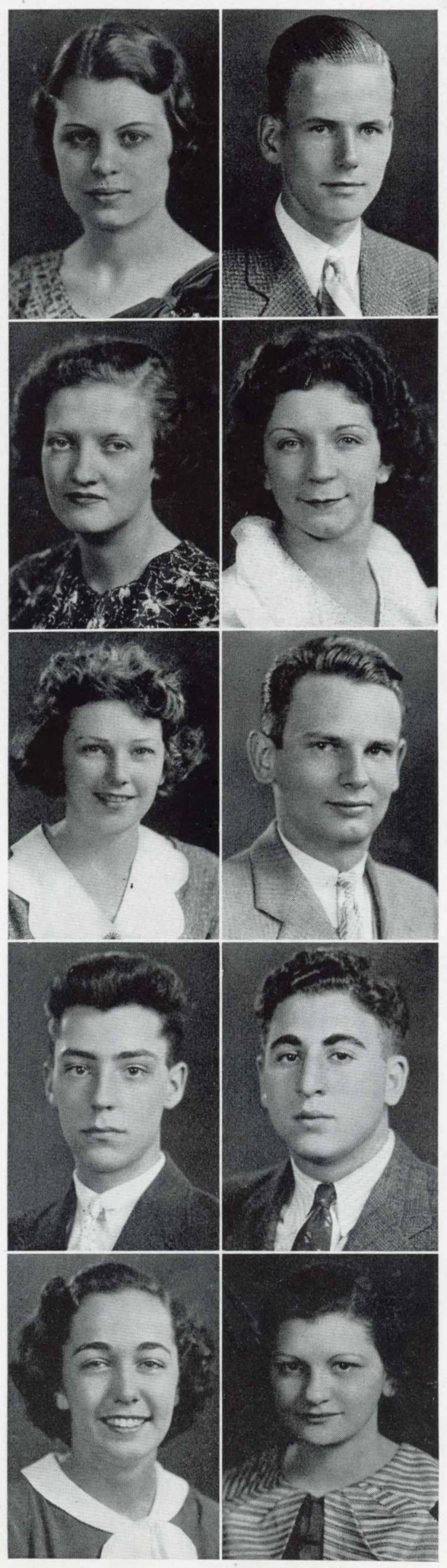

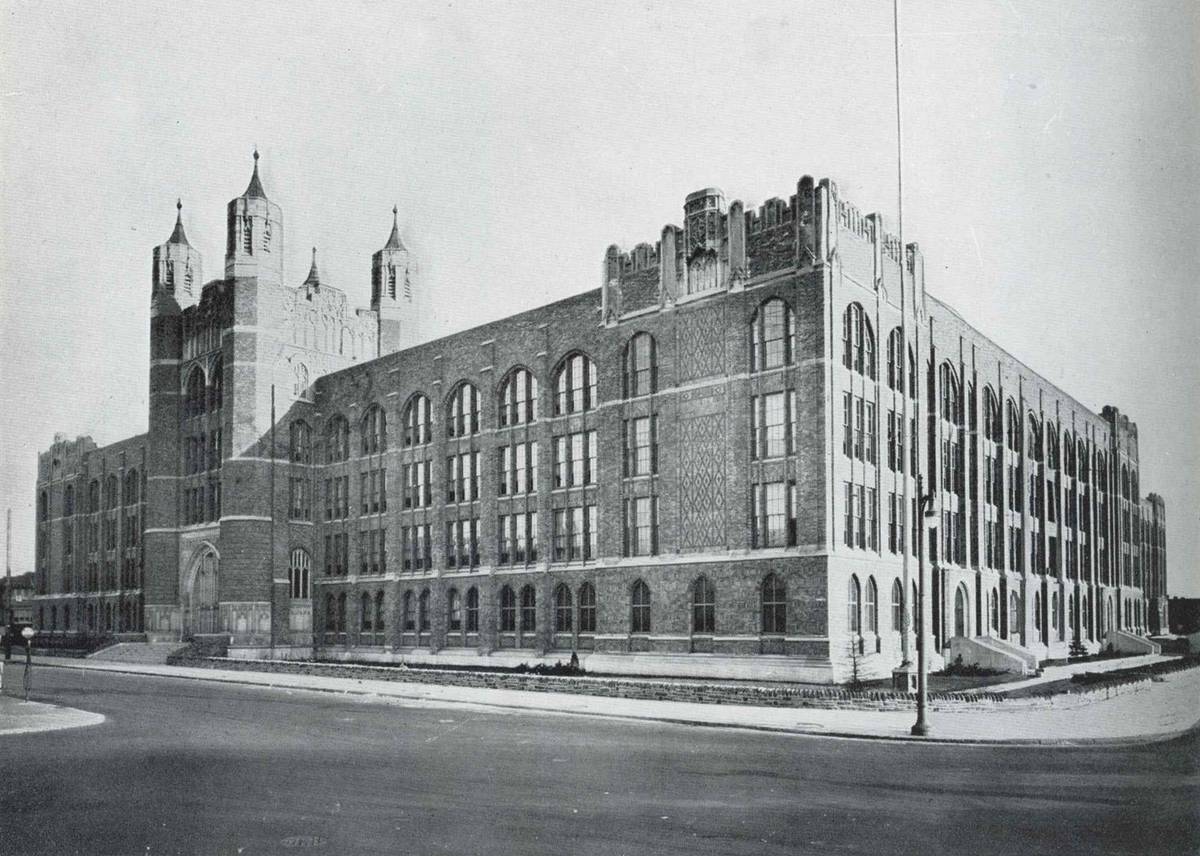

The coat with the ermine, pilgrim-style collar could also have been her winter wrap when she graduated from Simon Gratz High School in January 1936. While I don’t have photographic proof, I do have her yearbook, the Gratzonian, where Paula Wohlfeld is pictured with her peers in many clubs. In one she is with the Gratzonian staff, and credited as its personals editor, the team that wrote bios for the 400 graduates.

But these black-and-white images only begin to tell the stories about the community that nurtured her, and what she left behind after high school, four years at Pennsylvania State University, and a move with her new husband in 1941 across the state to a largely Jewish community in Pittsburgh called Squirrel Hill.

My journey is like eavesdropping on the family at 4546 North 12th Street, the Philadelphia address written in the Gratzonian, where she lived with her parents, Yetta and Joseph, and younger brother Alvin.

The neighborhood is Logan.

Records from Beth Sholom, Logan’s first synagogue, refer to the neighborhood as the “suburbs,” said Michael Schatz, a Jewish educator, historian, and tour guide of Jewish Philadelphia. “It starts to fill up with Jewish families and remains predominately Jewish from the 1920s through the 1950s.”

When Paula Wohlfeld attended Simon Gratz, Logan was labeled “J” (Jewish) and “D” (Decadent) on J.M. Brewer’s Map of Philadelphia that redlined the racial and ethnic makeup of the city. Brewer, once the chief appraiser in Philadelphia for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and among the largest lenders in the city, provided his maps to local lenders, real estate agents, and appraisers, with the disclaimer: “All location ratings and racial concentration quotes are the opinion only of J.M. Brewer after careful investigation of the location.”

The Wohlfelds were at North 12th Street as early as 1924, according to a postmarked (empty) envelope with their address. Schatz labels Logan a “second-settlement” immigrant community. “The Wohlfelds, like their neighbors, probably had moved further north beyond their German and Austrian immigrant [Philadelphia] ghettos, to carve out a better life for themselves and their children in Logan,” he said.

Logan was then a thriving community, with a subway stop. Three synagogues, Beth Sholom and Beth Judah, both Conservative shuls, and B’nai Israel, an Orthodox shul, served congregants in the tightknit neighborhood. “There was a mikvah in the neighborhood, and lots of kosher butchers,” Schatz added, adding that at one time there were some 500 kosher butchers across Philadelphia.

Curiously, my mother lived next door to the Beth Sholom rabbi, a great friend of the family, I learned from a rare video with her I found as I wrote this story. And he wasn’t the only rabbi on the block—far from it.

Logan was dotted with row house shuls known as shtiebels, places where an Orthodox rabbi would attract a minyan into his home to pray, a common practice in Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. “Shtiebels popped up in South Philadelphia in the early 20th century and moved into Logan to serve the Jewish community,” Schatz said. In “The Last Row-House Shul,” published in the Forward in 2013, Howard Shapiro wrote: “These buildings were hives of activity on Saturday mornings, when worshippers packed into confined sanctuaries that otherwise would have been used as stores or living rooms.”

Another symbol of Jewish life was the Jewish Hospital, today the Einstein Medical Center on Old York Road, founded in 1865 to care for Jewish Civil War veterans. On its campus was the Jewish Sheltering Home (1882), which became the Home for Jewish Aged (1899). The community, Schatz added, also had movie theaters and Jewish-owned businesses on and around Broad Street, the main thoroughfare in the city.

The Wohlfeld family most certainly purchased pastries from one of three Jewish bakeries on 11th Street including the German bakery, predecessor to Rosen’s Famous Bakery, owned by Rita Rosen Poley’s parents, Sam and Ida, immigrants from Russia and Ukraine. Rosen Poley, born in 1942, lived with her two siblings above the bakery, a seven-days-a-week, around-the-clock operation. “At its height [we had] 20 or 30 people working in the cake and bread shops, staffing the store, cleaning, and making deliveries,” she said. “The only time we got a break was the week of Passover, when the bakery was closed.”

Rosen Poley said family life revolved around the Jewish calendar. On Sukkot she and her cousin Linda were charged with taking a supersize challah to Synagogue Beth Judah of Logan, where her father was president of the congregation. “We felt like royalty walking up the street to [deliver it] to the sukkah.”

“It was just a very happy place to be,” she said of the neighborhood. “I think all of us who grew up there were part of the magic of Logan at 11th Street and [will] always keep that magic with us.”

What became of the neighborhood’s magic? Schatz said that as families became more affluent, “they had an eye on a little piece of land or a newer bigger house in the suburbs and moved out.”

The Jewish community my mother knew as a girl would change block by block with businesses and synagogues shuttering. By the mid-1980s, in an area called Logan Triangle, houses—built in the 1920s over a 60-foot layer of coal ash and cinder blocks—began to sink. Their foundations cracked, as the land slowly subsided. “I remember as a teenager the city had to get everyone out of their houses, and they condemned and tore down the whole neighborhood,” Schatz said: 957 row houses, 17 square blocks. “[It’s] like a prairie, streets go through but nothing on the block[s].”

By this time most of the Jewish people had left.

While he has led Logan bus tours, Schatz said, there are very few signs of Jewish Logan today. “The Beth Sholom building is still there. B’nai Israel’s building became a church. The Jewish Hospital of Philadelphia is still there, and on its grounds, a tiny synagogue,” he said. That Henry S. Frank Memorial Synagogue was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

As Jews left, other racial and ethnic groups moved in, largely African American, but also Latino and Asian.

Charlene Samuels, director of constituent services for at-large Philadelphia City Councilwoman Helen Gym, bought a row house in Logan in 1992 and raised two daughters there. Early on, she volunteered with school and community groups, and by 2016 founded the Logan Civic Association, which she chairs, to reduce both blight and crime. She described Logan today as predominately African American, but also “a melting pot of cultures, attracting working class people, both renters and homeowners.”

“Unemployment in Logan is among the highest in the city, as is the poverty rate,” she added.

Samuels said Gym encourages her activism: “I remember saying to her when she wanted to hire me, ‘Well you know I’m very involved in my community. How’s that going to work?’ And she says, ‘No, Charlene, that would be a plus. I wouldn’t want you to stop.’”

“I believe that Logan is a great place to live. I really do,” Samuels said in an interview with the Logan Public Library in December 2020. But she acknowledged the gun violence that has given Logan a bad name. She said it is unacceptable that gun stores could remain open during a pandemic: “Wait a minute, how is a gun shop ‘essential’?”

But the challenges are enormous. Last year, gun violence took the lives of nine students from Simon Gratz, my mother’s alma mater.

Samuels is calling for limits to gun access, and promotes education and models of empathy to break the cycle of violence. “We need to look at ourselves and help each other embrace some of these generational curses that have been on the Black and brown community,” she said. “We’ve got to do better. We’ve got to change the dynamics.”

It’s that decision to do better that my great-grandparents made to immigrate, fleeing political unrest, poverty, and persecution. They began life in a crowded New York tenement, and a generation later Paula Wohlfeld, my mother, would grow up in Logan, with strong ties to the Jewish community.

As part of that community, Paula Beatriz Wohlfeld headed off to make her future in her stylish black velvet coat.

Rosanne Skirble worked for many years as a reporter for the Voice of America and currently freelances for local and national publications from her home in Silver Spring, Maryland.