The Many Faces of the Dybbuk

Rokhl’s Golden City: Multiple versions of the spooky story—the good, the bad, and the drek

There are dybbuks at the heart of American Judaism. Or at least, they’re currently haunting the lobby of Hebrew Union College‘s New York City campus. They’re part of an exhibit up now through January called Magical Thinking: Superstitions and Other Persistent Notions. The show covers a broad terrain—perhaps a bit too broad, for my taste—of mythical monsters, invisible dangers, and protective folk practices.

Among the many pieces on view at HUC are, of course, various dybbuks, as well as multiple reinterpretations of the golem, plenty of red strings, and a beautiful paper-cut protective amulet. I particularly liked Joyce Ellen Weinstein’s linoleum block print “Solomon Ibn Gabriol’s Female Golem” pictured with wild hair and broom in hand, as well as well as Maj Kalfus’ “Clara.” Kalfus’ grandmother Clara was apparently so fearful of the evil eye that, according to the description, she would “avoid strangers who looked at her family” and “would not show photos of her children and grandchildren even to friends for fear of the Evil Eye.” The painting is a fairly normal portrait of a woman, but with blank spaces for eyes, lending the piece an incredibly eerie feel.

However, an art exhibit can’t really give you the high-quality spookiness you may find yourself (or myself) longing for when October rolls around. No, for extended Yiddish spookiness, we must turn to the movies. The Dybbuk (1937) is “the sensual, spooky, aesthetic high point of Yiddish cinema” as I wrote in 2019. The film was an adaptation of S. Ansky’s play, which had its debut in 1920, and was itself based on a folk legend he collected on an ethnographic expedition and then reworked. In the play, a beautiful young woman (Leye) and studious young man (Khonen) long for each other, but Leye’s father, Reb Sender, promises her to a wealthy match. Khonen attempts to use kabbalistic magic to attain the money he needs to win Leye, but he dies in the process. His restless spirit possesses Leye before she can be married off, and she, too, dies, as a wonder-working rabbi attempts to exorcise Khonen’s spirit out of her body.

Many, many words have been written about director Michal Waszynski’s beautiful, if slightly overlong, adaptation. Obviously, if you’ve never seen it, you’re in for a special treat. The film was remastered and reissued on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber in 2019. While you wait for your DVD to arrive, you can watch a snippet of one its most famous scenes, where the doomed bride Leyele does the Dance of Death with the townspeople.

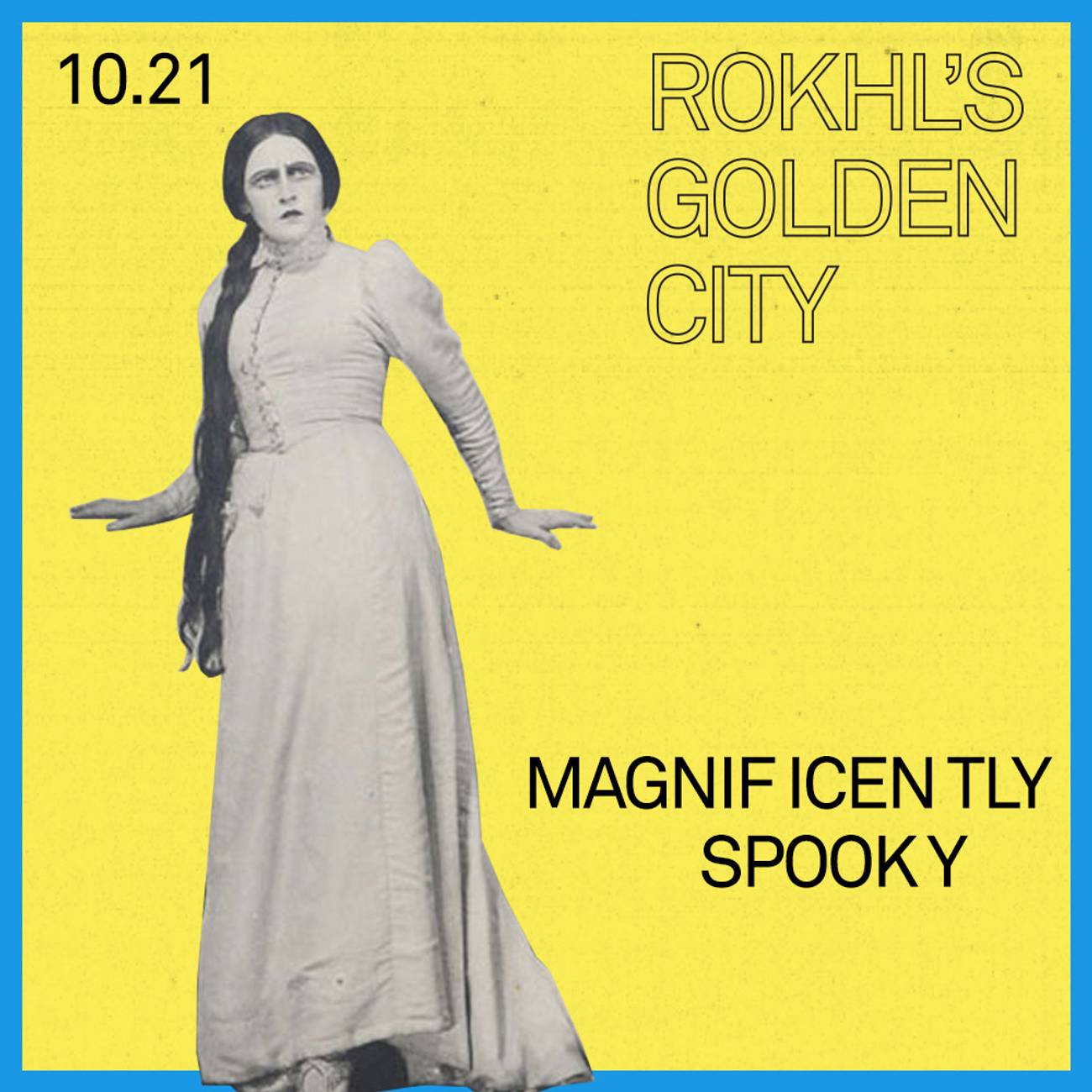

In Israel, the role of Leyele was forever joined with her most famous interpreter, Habimah’s Hannah Rovina, the “high priestess of the Hebrew theater.” She first played the role of Leyele (in Hebrew) in 1922, when she was already 34, and continued playing the doomed teenager until 1957. Rovina was not the kind of artist who let age stand in her way. She had her first and only child when she was 46!

Rovina passed away in 1980, but is still iconic in Israel. For decades her wax likeness appeared as one of the celebrity figures at the (very spooky) Shalom Meir Tower wax museum in Tel Aviv. A few years ago, the Israeli sketch comedy show Ha’yehudim Ba’im aired a wickedly funny skit based on the premise “Hannah Rovina has a cold.” Despite so many American comedians and comedy writers being Jewish, it’s impossible to imagine something so specifically Jewish appearing on mainstream television. And really, how many Americans today have even seen The Dybbuk? It can’t be many, because I know, without a doubt, that if more people had seen the movie, a Leyele costume, with powdered face, white dress, and long black braids, would be an absolute staple of every Halloween (and Purim) party.

One of the things I love about this Ha’yehudim Ba’im skit is how it demonstrates the fine line between genuine spookiness and melodramatic kitsch.

At least a few Americans saw The Dybbuk in October 1960, when an English-language adaptation appeared on network TV as a Play of the Week. It was directed by a young Sidney Lumet and featured stars like Theo Bikel, Carol Lawrence, and Vincent Gardenia. Sure, Carol Lawrence is missing Leyele’s iconic braids, but she brings an understated fragility to her performance, well suited to the medium of television.

Yes, they make the baffling decision to pronounce Yiddish names as modern Hebrew, Khonen becoming Khanan, and so on. Even so, I think The Play of the Week production has a lot to recommend it. For one thing, it makes accessible the kind of spooky folklore I found missing from the HUC exhibit, such as the ritual visit to the cemetery before a wedding in order to invite the bride’s parents, and all the beliefs that go along with that. The Play of the Week script directly translates large parts of the original Yiddish text. It’s got some cool moments of music and dance. And it’s not lacking in well-executed spooky moments, either.

Apart from Leyele’s braids, however, something important was missing. The story hinges on would-be bridegroom Khonen’s use of forbidden kabbalistic magic to win Leye’s hand. This production discreetly cuts many if not most of the original’s references to acts of dark magic. It seems to me that you need those magical stakes established at the beginning if you’re going to close the story with the side of magical “good” fighting for Leye’s soul.

If you want to see a modern, Yiddish-language adaptation of Ansky’s text, the Congress for Jewish Culture streamed a superb new Dybbuk in 2020, in honor of Ansky’s 100th yortsayt. Not quite filmed theater, not cinema, not television, this production is very much of its moment. The magnificent Yelena Shmulenson dons Leyele’s iconic braids for this adaptation.

Shmulenson played a very different kind of role in the prologue to the acclaimed Coen brothers 2009 film A Serious Man. With her real-life husband, and frequent artistic collaborator, Allen Lewis Rickman, she plays a no-nonsense shtetl resident whose husband (Rickman) inadvertently invites a dybbuk (Fyvush Finkel) home for soup.

I’m not much of a fan of the Coen brothers, and A Serious Man is no exception. But oh, this prologue. Magnificently spooky. If only there were a way to get a whole movie about this couple, and the dybbuk-haunted landscape they inhabit.

Even though the Serious Man prologue got a ton of attention and praise, Hollywood, it seems, was not listening to the clamor for more Yiddish dybbuks. Alas and farkert (just the opposite.) In 2009 we also got The Unborn, in which a young woman discovers the spirit of her stillborn twin is now haunting her as a dybbuk. Throw in an extremely tasteless Holocaust subplot, and Gary Oldman as a rabbi, and I simply could not bring myself to watch this one. If you’ve seen it, let me know if The Unborn it is as truly drekful as it sounds.

A whole new wave of dybbuksploitation kicked off in 2012 with The Possession. I actually saw this one in the theater, which did nothing to enhance my (non)enjoyment. Spooky it was not.

The Possession introduced a new element into cinematic dybbuk lore: a “haunted” wine box whose spirit possessed a little girl. It also claimed to be based on a true story. Upon investigation, the “true” in true story turned out to be somewhat generous. To briefly summarize, a purportedly dybbuk-haunted wine box was placed for sale on eBay in 2004. Those who came into contact with the box claimed to be victims of its curse. I went into a bit more detail on my blog in 2012 and I reviewed the book that inspired The Possession that same year. As I wrote in my review, the haunted wine box had the threatening aura of a synagogue gift shop trinket. The story as a whole had the flavor of a “Manischewitz martini” whose “clashing ingredients” made the whole thing “hard to swallow.”

Where I found the dybbuk box concept ludicrous, the movie industry saw dollar signs, and not just in Hollywood. In 2017 a Malayalam-language movie called Ezra was released for Indian audiences, capitalizing on the haunted dybbuk box idea. Ezra is available to stream for free on YouTube, but without subtitles. My Malayalam is rusty, but the movie was remade in 2021 as Dybbuk: The Curse is Real, and this time the Hindi dialogue came with English subtitles. Comparing the two versions, I found that the 2021 remake appears to track the earlier film almost exactly.

So how do you adapt a movie about a Jewish spirit for a market with barely any Jews? Well, the dybbuk box concept fairly neatly obviates the need for actual Jews in your story. In The Curse Is Real, the movie opens on the island nation of Mauritius, where the last Jew on the island has died. An antiques dealer makes the error of taking items from the dead man’s home to his shop. One of those items is, indeed, a haunted wine box. The wine box is bought by a newly married woman (Mahi) as decoration for her new home. Shortly thereafter, bad things start happening to Mahi and her husband, Sam. This eventually leads them to seek help deciphering the meaning of the box, and ultimately, to two rabbis at the Mumbai Chabad house.

Let me be the first to say that I long to see a diversity of Jews portrayed on screen, especially Southeast Asian Jews. But let me also be the first to say, oh my God, this ain’t it. The “Chabad house” rabbi shows up in a black button-down shirt, priest’s collar, and giant six-pointed star necklace. And it doesn’t get any better from there. The Curse Is Real is full of cheap jump scares and paper-thin characters.

The biggest problem with The Curse Is Real isn’t the rabbi dressed like a priest. After all, this isn’t a movie made for me, and that’s fine. But the climax of the film, the exorcism of the dybbuk, trades in some dangerous, medieval antisemitic tropes. (Spoiler alert.) The “curse” of the dybbuk box turns out to have been placed on the island by a wealthy, vengeful Jewish trader. When the man’s son gets a local girl pregnant, subsequently abandoning her, her family takes revenge on the boy. In turn, the boy’s father calls on kabbalistic black wizardry to place his dying son’s spirit in the box. This scene uses imagery straight out of a B-movie about satanic magic, complete with a pentacle drawn on the floor surrounded by candles. Joshua Trachtenberg would be appalled. These are the kinds of stereotypes that get Jews killed. Definitely not spooky. At least not in the good way. And it made me sympathize with Lumet’s decision to cut those kinds of references from his 1960 televised Dybbuk. The horrors of the past are not always as distant as we would like to think.

Given all the dybbuk-drek out there, I was very, very pleasantly surprised to find Demon (2016), a Polish-Israeli coproduction shot in Poland. Where Dybbuk: The Curse Is Real reduces the Jewish element to a prop in an otherwise generic possession story, Demon is a thoughtful take on the dybbuk story, heavy on the atmosphere and shot through with dark humor.

The movie opens as we meet Piotr, a son of the Polish diaspora in England. He arrives in a rural Polish village where he is set to marry his new girlfriend, Zaneta. With the help of some heavy construction equipment, Piotr accidentally uncovers some very dark secrets, and, before the wedding celebration is over, he finds himself possessed by a Yiddish-speaking spirit. The movie takes elements from The Dybbuk (1937) such as a thwarted marriage, eerie wedding dance, and, of course, possession, and combines them into a movie that actually has something to say about Polish, Jewish, and Polish-Jewish history. An Israeli actor, Itay Tiran, plays Piotr, and he is absolutely phenomenal. If you’re like me and you like slow-burn spooky horror, you will love Demon. It’s the kind of movie that reminds us that there are still haunted landscapes to be explored, and that as a genre, horror still has much to add to the conversation.

PET PEEVE: I know this is a battle I will never win, but “bubbe meises” or “bobe-mayses” are not “grandma’s stories” or “old wives’ tales,” as one of the descriptions of artwork in the HUC exhibit tell us. The bobe in bobe-mayse is a false cognate with bobe (grandmother), instead coming from a 16th-century Yiddish translation of a knight’s tale called the Bovo Bukh. In Yiddish, a bobe-mayse is a cock-and-bull story, a fantastical piece of BS someone might try to sell you. There is already a Yiddish term for old wives’ tale or superstitious belief, one just as misogynistic, if you really need it: vaybershe zabubones, silly superstitions held by wives and other women.

ALSO: Sholem Aleichem Cultural Center will present “Yehoash: His Life and Work,” a lecture by Sharon Bar-Kochva. In Yiddish, via Zoom, Oct. 23. Free, registration required … Artist Debra Olin’s exhibit Every Protection: Exploring Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Jewish Pale of Settlement opens at the Yiddish Book Center with a Community Open House, Oct. 23. More information here … The Tenement Museum presents A Special Virtual Tour: Mystics in Manhattan, exploring “a hidden world of mystical beliefs and traditions” of New York’s immigrant neighborhoods. Oct. 27. More information here … If A Serious Man left you wanting more Yelena Shmulenson and Allen Rickman, and you happen to be in Germany this November, you can see them in Dresden, where they’ll be presenting “Tevye Served Raw” as part of Dresden’s yearly Jewish Music and Theater Week.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.