Marilyn and Alan Bergman on ‘Yentl,’ Israel, and What It Means to ‘Feel Jewish’

An excerpt from ‘Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish’ about the legendary husband-and-wife songwriting duo—after Marilyn’s death last weekend

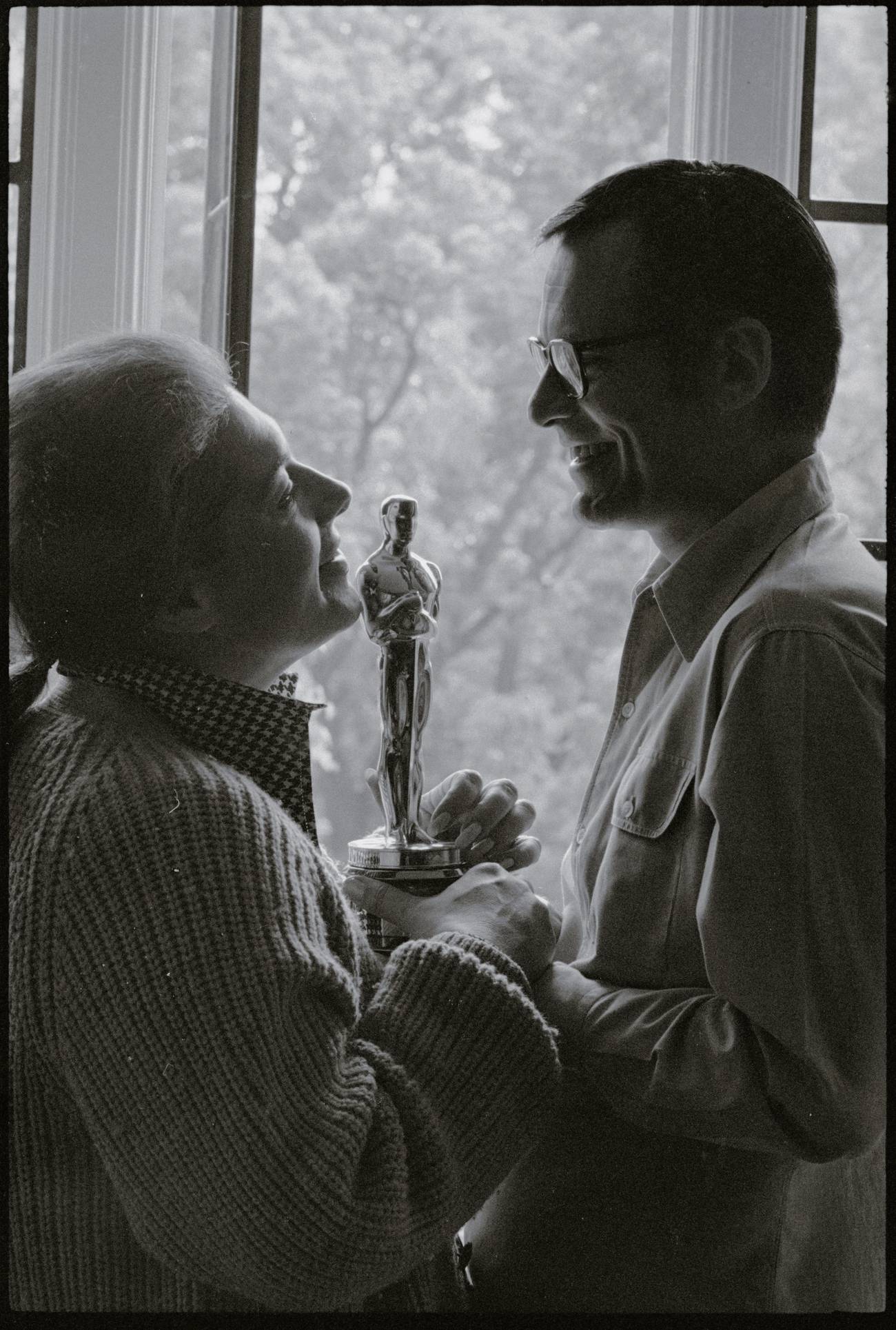

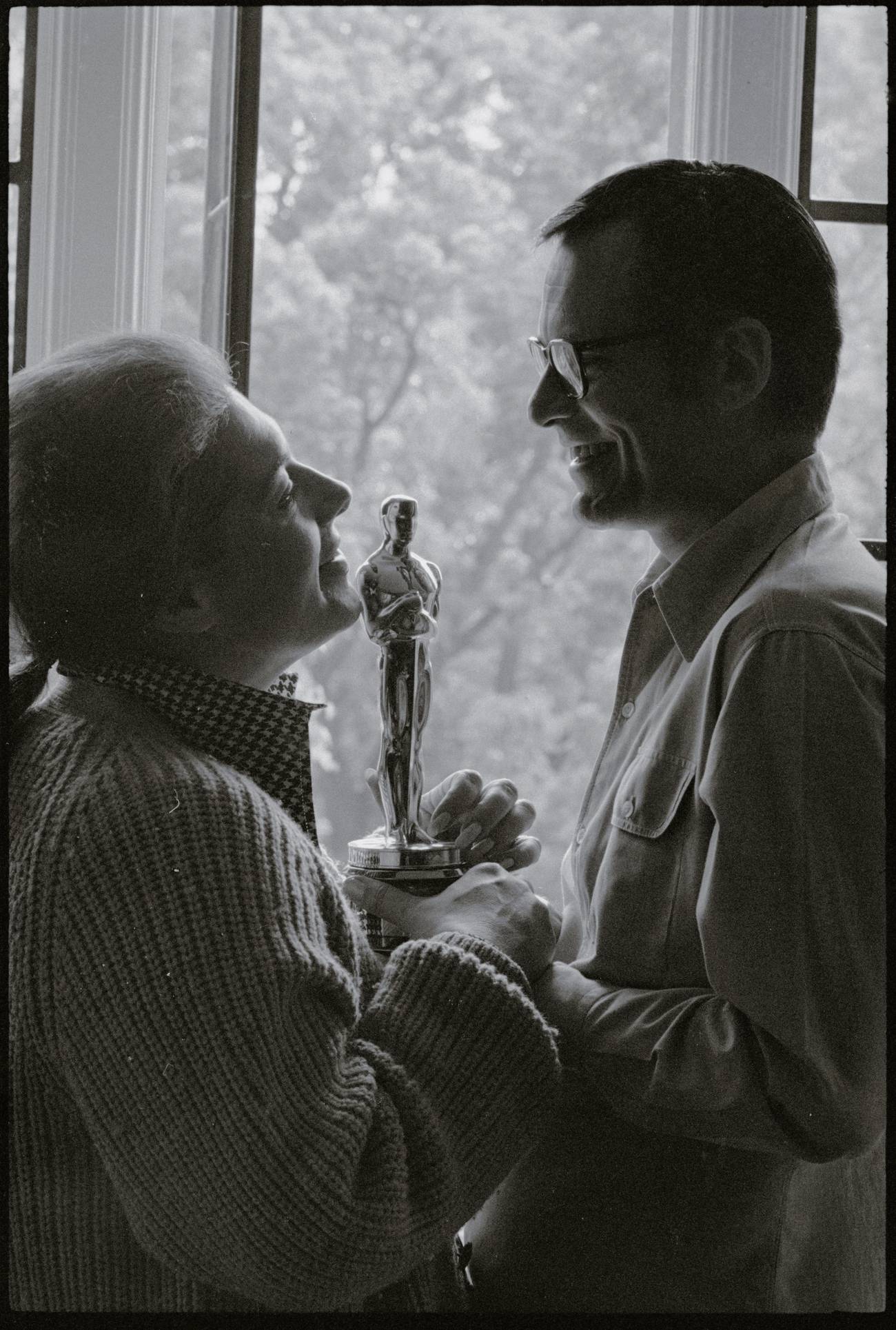

Alan and Marilyn Bergman, who have written most of Barbra Streisand’s most famous lyrics—from “The Way We Were” to “You Don’t Bring Me Flowers”—are sitting with me in the attic level office of their relaxed Beverly Hills home (on a high shelf, three Oscars, three Emmys, two Grammys), and somehow this couple has made me cry.

Alan, 80, was just telling a simple anecdote: how he started a ritual, years ago at the Jewish weddings he attended. “I always pick up the broken glass,” he says. “No matter whose wedding it is—”

“He’s done this for years—” Marilyn interjects.

“—and I put it in a glass box and we give it to the couple on their first anniversary. And it means so much to them. That connection—with each other, with history, with tradition. It’s so meaningful.”

In an instant I’m aware that I’m unaccountably choked up. I tell myself it would be ridiculous to show it, and then the next moment, my head is in my hands. “I’m sorry,” Alan says, “I didn’t mean to—”

“Oh dear,” says Marilyn, 76, who sounds teary now, too. “What is this about? Do you know why you’re crying?”

I’m not sure I do. It has something to do with a flash of recognition—of being linked to them and to anyone else Jewish: It’s about doing the things that for centuries have been done. That’s all. Those small acts, in and of themselves, bind and extend us. Stamping the glass under the chuppah is just one custom—most people don’t even know what it symbolized—but it makes a wedding Jewish, one couple to the next. As I imagined Alan bending over those shards, I suddenly wished someone had done that for me and my husband—and realized at the same time how that particular moment was irretrievable.

I have since learned that Alan’s gesture has become a cottage industry: one website after another—yidworld.com, Judaism.com, jewishbazaar.com, etc.—sells keepsakes for your crushed wedding glass: candlestick holders or mezuzot filled with the shavings you send in. When Marilyn mentions that she’s seen similar souvenirs advertised in The New Yorker, Alan seems mildly nonplussed. But that’s all beside the point. Something has been triggered for me, and the Bergmans are immediately parental, proffering Kleenex and nodding their heads empathetically.

I have to remind myself that these are people who hang out with “Barbra”—who, when I’d first arrived, told me they were exhausted from a late-night recording session with Streisand the night before. These two decidedly haimish grandparents are the songwriting team that became the first ever to receive three out of five Oscar nominations for best song in the same year, who penned the themes for The Summer of ’42, Same Time, Next Year, Tootsie, the television series Maude, Alice, and Good Times. Marilyn leans back with her feet up in her leather recliner—a casual throne of sorts—with her upswept hair and black turtleneck, looking majestic and earthy at the same time. Alan’s lanky frame is in an upright chair, catty-corner to his wife; his eyeglasses are too large for his face, but he’s worn the same size frames for decades.

The only time they’ve confronted their Judaism in their work was when they wrote the lyrics for Yentl, Streisand’s 1983 star turn as the Jewish girl so eager for a yeshiva education that she goes undercover as a boy.

“When we did Yentl, we did a lot of research,” Alan explains. They studied with two rabbis—one Reform, one Orthodox. “And as a result of that,” Alan continues, “a lot of waters were stirred in you,” he gestures to his wife, who nods. “It was the first time that there was ever some kind of historical context for me,” she says. “We met once a week for a year—Barbra, Alan, and I and a few other friends.”

“Laura put the Bible in a context of dreams,” Marilyn recalls, speaking of Laura Geller, senior rabbi at Temple Emmanuel in Beverly Hills. “Laura said, ‘When you have a dream, you don’t demand of it that it be linear, logical, literal, sequential—you don’t demand that of it.’ She said, ‘That is the way the Bible should be read: It is a dream of a people.’ I never had heard anything like that and it really clicked. It suddenly became such a personal way to view the heart and soul of Judaism.”

I’m curious as to whether they were worried about the movie being too Jewish; that had to be a concern. Marilyn says it was embraced more readily by non-Jewish audiences. “It was interesting; the picture wasn’t wildly successful in the places where we thought it would be—the Jewish enclaves like parts of Florida and New York. The most successful places were in the hinterland, in the Midwest.”

“I can tell you a very interesting story about that,” Alan chimes in, with an anecdote that illustrates the reluctance of Jewish audiences to openly embrace the film. “Yentl opened here for some hospital charity—a very rich, affluent group, mostly Jewish. And they sat on their hands. Because what was clearly going on in their minds was, ‘What are the goyim going to think?’”

“Yes,” says Marilyn. “That’s the important point: Jewish self-hatred and shame and paranoia. Everything is focused through ‘Oh, how does this look to gentile eyes?’”

“Three days later,” Alan continues, “Barbra, Marilyn, and I sneaked into a theater in Westwood—nobody noticed us. We sat in the back. And it was, I would say, maybe 35% Black.”

“Young—” Marilyn adds.

“Yeah, young,” Alan agrees. “And when the character, Yentl, gets accepted to the yeshiva, they stood up and cheered, ‘Yay!! Go!!’ It was a completely different reception.”

“In Yentl,” Alan continues, “the emphasis, so to speak, was a feminist approach to that story, more than the Jewish background. And maybe we didn’t think about the Jewishness—”

“Sure we did,” Marilyn scoffs. “Of course we did.”

“About worrying how it would sell—” Alan finishes his thought.

“Well, we knew that, by definition, it was going to be a niche kind of movie,” Marilyn says. “That it wasn’t going to be a hugely popular kind of movie.”

And how conscious were they of their songs—the music—having a Jewish feel and sound?

“It doesn’t,” Alan says definitively. “That’s why we chose Michel Legrand.” (French composer Legrand wrote over 200 film scores, including Wuthering Heights and Lady Sings the Blues.) “When the three of us were talking about a composer,” Marilyn adds, “we didn’t want, you know, The Yiddle with a Fiddle music.”

“Or even the Broadway conception of Fiddler [on the Roof],” Alan cuts in, “which is terrific, but we didn’t want that either.” Marilyn explains: “We felt that Yentl was a story of Middle Europe at a particular time. They happened to be Jews—but really it was an interior monologue of this young woman, and a great deal of it was very romantic, and I think we decided that what would make it more accessible—we probably did have accessibility in mind—was a composer who wrote European, romantic music.”

“And a love song, who would write for the instrument that Barbra has,” Alan says.

Judaism has not figured into their work since. In fact, the Bergmans have written Christmas songs, such as “Christmas Memories,” with lyrics such as “Singing carols, stringing popcorn, making footprints in the snow/Memories, Christmas memories, they’re the sweetest ones I know.” “I felt so deprived of that as a child,” Marilyn admits, “and I thought, ‘I can divorce it from any religious significance.’ Of course, hanging a wreath on my door, I would never do that.”

But her own daughter, Julie, did. That is, until Julie’s husband took it down. “It was only firs,” Julie says with a laugh (she’s stopped by her 5-year-old daughter, Emily). “Not a green ribbon or anything. It was just like a harvest thing. And my husband took it off and he put a note in its place on the front door that said, ‘The only wreath that will ever hang here is Aretha Franklin.” They all laugh.

Julie describes her parents’ Judaism as more political than spiritual (Malcolm X’s daughter was at their Seders, and their rabbi would often deliver provocative sermons.) But she’ll never forget her father’s annual, dependable comment about generational ties, which he imparted every year in temple on the High Holy Days. “I remember him always leaning over to me and whispering, ‘You know, Jews all over the world are doing exactly this right now,’” Julie says. “And I’d always roll my eyes—‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, you told me that already.’ But you get the importance of that when you’re older.”

Alan and Marilyn were coincidentally born in the same hospital—Brooklyn Jewish—and they both describe childhood bouts with prejudice. “I remember feeling gentile envy,” says Marilyn. “Seeing these girls on Sunday morning in their white dresses and their veils like brides, going to communion—oh, I wanted it so badly. And I made my mother buy me a cotton slip with lace on the bottom—she didn’t know why she was buying it for me—and one Sunday morning, I put on this slip and I put a sweater over it, because it was, after all, a slip, and I went out thinking I was going to be able to join this beautiful tradition. And the girls laughed at me and said, ‘Oh, Marilyn’s out in her underwear!’ I must have been about 5 or 6 at the most.”

Alan was older when he felt shut out. “I was a pretty good Ping-Pong player, and I wanted to learn how to play tennis. The Nationals, which were the predecessor of the U.S. Open, took place in Forest Hills, in a white-glove club which was restricted. I went there—from Brooklyn, you had to take a bus and a trolley—and asked, ‘Who hires the ball boys?’ I figured if I was a ball boy, I could learn how to play. And the man in charge said, ‘What’s your name?’ I said, ‘Alan Bergman.’ He said, ‘Go home.’ Well, I had chutzpah in those days and I said, ‘Well, I’m a pretty good Ping-Pong player. I’ve won a couple championships; I’m going to go to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and tell them you won’t let me in because I’m Jewish.’ He said, ‘You come back tomorrow.’ I said, ‘I can’t come back tomorrow; it’s too expensive.’ And he finally relented and I was a ball boy for two years and that’s how I learned to play tennis.”

“He’s a very good player,” Marilyn interjects.

“Well …” Alan demurs.

Marilyn’s grandmother was a Russian immigrant who was firmly Orthodox. “All I remember about religion was that it was inconvenient and unpleasant,” Marilyn says. “God forbid you should put the wrong fork in the wrong drawer or use the can of kosher soap with the red on it, when I should have been using the blue. I just remember it was rigid.”

But when she went to Israel for the first time, she was overcome. “I remember being on the airplane with the Israelis—when they sighted land, they started singing ‘Hatikvah.’ Well …” Her eyes fill. “We stepped off the plane and you saw Jewish soldiers and Jewish policemen and Jewish everything: It was overwhelming. But look what they did, how they fucked it up.

“I always talk about this,” she continues, “but George Steiner—the philosopher—wrote a piece in 1948 about his fears for the creation of the state of Israel. And he said the reason that Jews all over the world have made contributions in all kinds of disciplines—way in excess of their population—is because they were outsiders. They couldn’t own land, couldn’t go into business, couldn’t be soldiers. They didn’t have a flag or an anthem or a boundary. Being on the outside, they were observers, commentators—through art or whatever else. And he warned the Jews of Israel that this could be the beginning of the end. And oh boy, I think about that piece more often than I care to. Very prescient and true.”

For the Bergmans, longtime progressives, politics and religion seem inextricable. “If you take Jews out of it, the liberal movement is a very lonely place,” Marilyn says. “That’s true everywhere. Which is one of the reasons I think we’re a political endangered species … The larger question you’re getting at is deeper, though: What does it mean to feel Jewish? I don’t know. It’s such a rich soup.”

“I’m sure if you would ask people,” Alan says, “’Would you rather be something other than Jewish?’ you would get the answer, ‘No.’”

“Oh, it’s inconceivable,” says Marilyn. “It’s essential.”

Excerpted from Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish by Abigail Pogrebin. Copyright 2005 by Abigail Pogrebin. Used by permission of Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Abigail Pogrebin is the author of Stars of David and My Jewish Year. She moderates the interview series “What Everyone’s Talking About” at the JCC in Manhattan.