Missing in Action

Keeping alive the memory of my uncle, lost at sea in WWII

More than 73,000 U.S. military personnel of WWII are missing in action to this day, according to the Defense Department—including my Uncle Roy. A weathered stone in our plot in the Jewish cemetery in Mobile, Alabama, reads simply: “In Memory of Roy Robinton, U.S. Marine Corps. April 12, 1911-Dec. 31, 1944. Lost at Sea, World War II.”

Maj. Robinton was a stalwart youth with black hair and dark, tender eyes looking back at me from photos faded with time. My mother’s big brother, he played violin to her saxophone, drove with her to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, entered ROTC at the University of Alabama while she stayed home at the store. Although he was gone long before I was born, his absence was a presence that grew each Memorial Day, birthday, and special occasion. In the 1950s and ’60s, I came of age with his story.

Roy fought with the 4th Marines in the Battle of Corregidor and in May 1942 surrendered with Allied forces to the Japanese. After more than two years in a Manila POW camp, he was herded with 1,600 others into the airless hold of a Japanese freighter, the Oryoku Maru, bound for Japan as slave labor. Allied bombers, not knowing POWs were aboard, sank the vessel. Roy was then put on the Enoura Maru, another “hell ship.” He never returned.

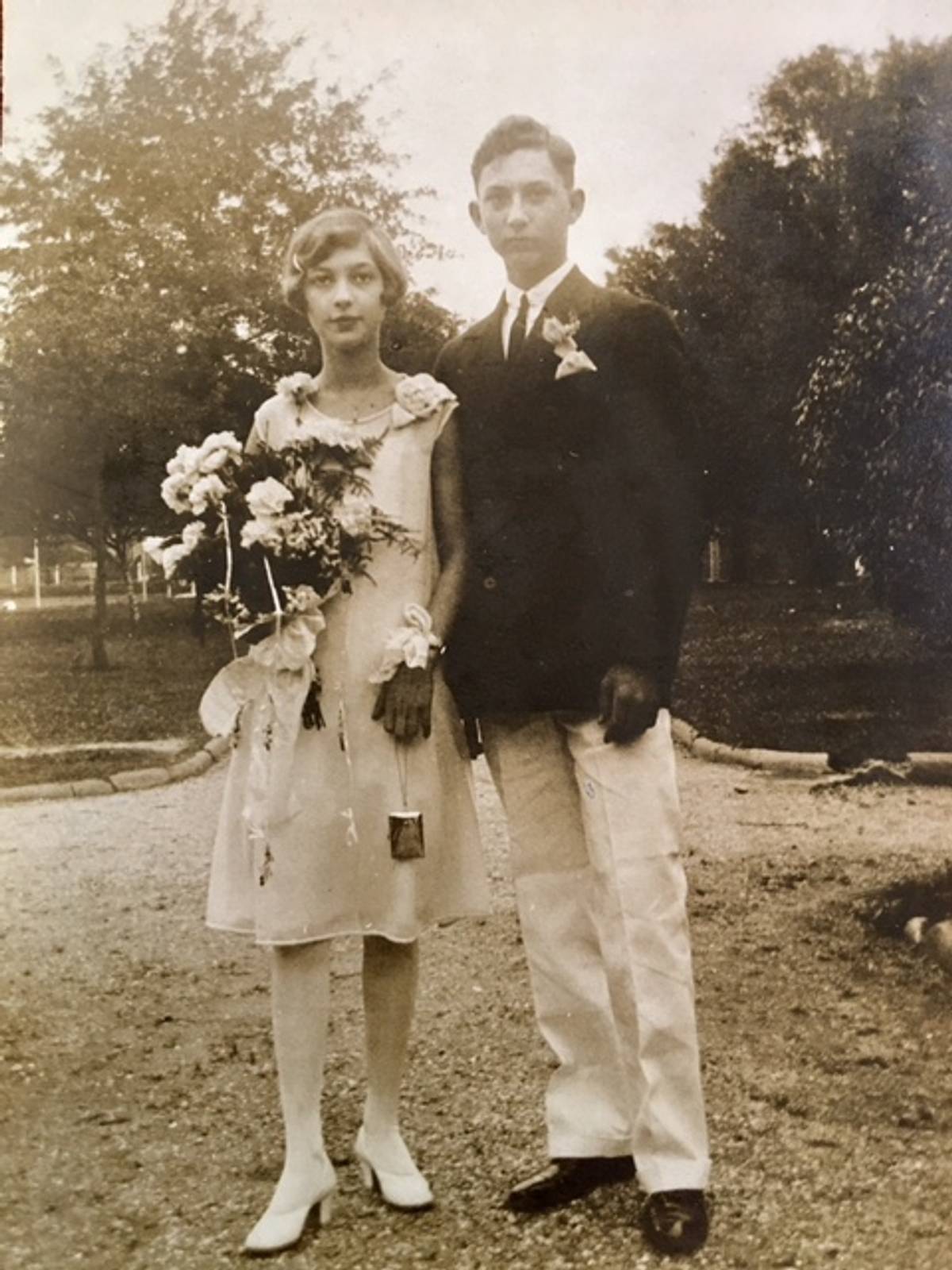

Roy left behind a young bride, Irene, who was ground down by waiting—the painful uncertainty, the not knowing. This made an impression on me as a teen. The wedding portrait of Roy and Irene was glamorous, one my mother took out to show me often, though she always tucked it away again, as if it were too precious to prop alongside others on the mantle. In full military dress, Roy stands handsome, proud, with beautiful, blonde Irene, gown sumptuous and flowing.

It is still hard for me to look at the golden couple, knowing their fate.

Once Roy was in enemy hands, 10 months would pass before there was further word. In Alabama, as my grandparents waited—grandfather Aaron, a Russian-Jewish immigrant in Mobile, and grandmother Sadie, of German-Jewish lineage—even scant news was cause for celebration. As Sadie wrote to Aaron’s brother and family in Morvin, Alabama, on March 18, 1943:

Dear Brother Benn: Your letter made us all very happy today. It was the climax to a perfect day. At 4:30 this afternoon, Irene called me from Washington, D.C. saying she had official news that Roy is alive, and a prisoner of war.

Months later, the family received an index card about Roy’s condition, a report on prisoners from the Japanese Imperial Army via the International Red Cross: “My health is: good.” “I am: well.” That card is gone but I see it still, in my mother’s trembling hand.

The war ended in 1945 but Roy did not come home. There was a report he’d been killed in action, but few details. A survivor of the hell ships visited Mobile and shared what he knew about Roy’s last moments when the vessel was strafed by an Allied bomber. But there had been chaos; the facts were unclear.

The family was reeling, and Roy’s wife, my parents told me, suffered a nervous breakdown. My grandfather wanted his boy home for his final resting place. After writing desperate letters to officials he received this response from the Graves Registration Department of the Eighth Army in San Francisco. It was June 16, 1947, two years after the war.

…your son left Manila, December 13, 1944, aboard a Japanese ship. The ship was attacked by planes at sea and put in at Subic Bay where, on December 15, 1944, it was again bombed and sank a short distance from the shore. The majority of the prisoners, including your son, reached the beach where they were recaptured by the Japanese. They were then taken to San Fernando on the Bataan coast and embarked on another ship for Japan. This ship was also bombed off Formosa the latter part of December 1944, resulting in many casualties, and the Japanese reported your son killed. In the absence of an exact date of death it was determined, for official purposes, that his death occurred on December 31, 1944. I regret to inform you that your son’s remains were not recovered.

I can imagine my grandfather peering down at those words, all he had left of his son.

Even though Roy and Irene had no children, there were legacies. On August 1, 1946, my parents named their third child, a daughter, Robbie—Roy Robinton’s nickname in the service. On June 23, 1953, they had their fourth and last child, and wanted to keep the memory alive, burnished still. In his memory, I was named Roy.

In 2012, I flew from Mobile with 107 WWII veterans to Washington, D.C., as part of Honor Flight South Alabama. My role, along with 60 others of my generation, was that of “guardian”—to assist our elders of the Greatest Generation, many with walkers and canes, on their day-long visit to sites including the National World War II Memorial and Lincoln Memorial, and the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery. Because of my age, I was the last birth year to be subject to the draft through the lottery system, but the draft was abolished before they started signing us up. My ongoing connection to the military was through the stories my dad had told me about his service, the reminiscences I heard from the vets around me and others, and, above all, the saga of Uncle Roy. He was very much on my mind in D.C.

I’d been to the nation’s capital many times, once in the 1970s with my parents, who’d contacted Irene. By then she’d long made a new life for herself, married to a kind, understanding man who’d also been military. They invited us to an officers club for lunch. When she looked at me and said my name, her eyes misted over. She told me proudly about the family that she and her husband had created, their children and grandchildren. Many years later, in 2004, I was signing at a bookstore in Birmingham when a young woman appeared, introduced herself as Irene’s granddaughter, and told me that her grandmother, now in twilight confusion, had started asking about her beloved Marine. Was there any news of him? My mother, in her last months of decline, asked me the same. These were shots to my heart that propelled me to write a novel inspired by my uncle’s tale and those who’d waited at home.

Roy was forever, in their minds, a shining officer of 33. I wanted to keep him vivid in my own way.

With the WWII Honor Flight veterans, as we visited the unknown soldier’s tomb, I wondered who might lie there. On the stone’s side is inscribed: “Here rests in honored glory an American soldier known but to God.” How many through a century of wars might have thought, “Could it be my husband, my brother, my son?”

This need to find the missing and unrecovered—to gather them in, to see them off in a fitting way—is primal. In 1998, DNA testing of the remains in the Tomb of the Unknowns gave several families hope that a Vietnam-era casualty might be theirs. Eight families waited desperately for word of the findings. When the tests were done, it was determined that the unknown was First Lieut. Michael Blassie, a pilot killed in Vietnam. He was disinterred and buried with military honors at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, placed near the grave of his father, who’d served in WWII.

Twenty-five hundred years ago, the Greek historian Thucydides wrote of Pericles’ Funeral Oration to the Athenians after the first battles of the Peloponnesian War: “There is a funeral procession in which coffins of cypress wood are carried on wagons. There is one coffin for each tribe, which contains the bones of members of that tribe. One empty bier is decorated and carried in the procession: This is for the missing, whose bodies could not be recovered.”

Countless others must find closure in their own way, even when there is no hope that loved ones will return. Whatever befell them and wherever they lie may be unknown, but not their impact on our lives. We create our own homecomings.

Roy Hoffman is the author of Come Landfall, a novel inspired by the story of his uncle, now reissued in paperback.