The Power of a Circle: Standing Hand-in-Hand to Overcome Discrimination

Listen to Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1958 speech at my synagogue, and you’ll understand how his words continue to inspire activism

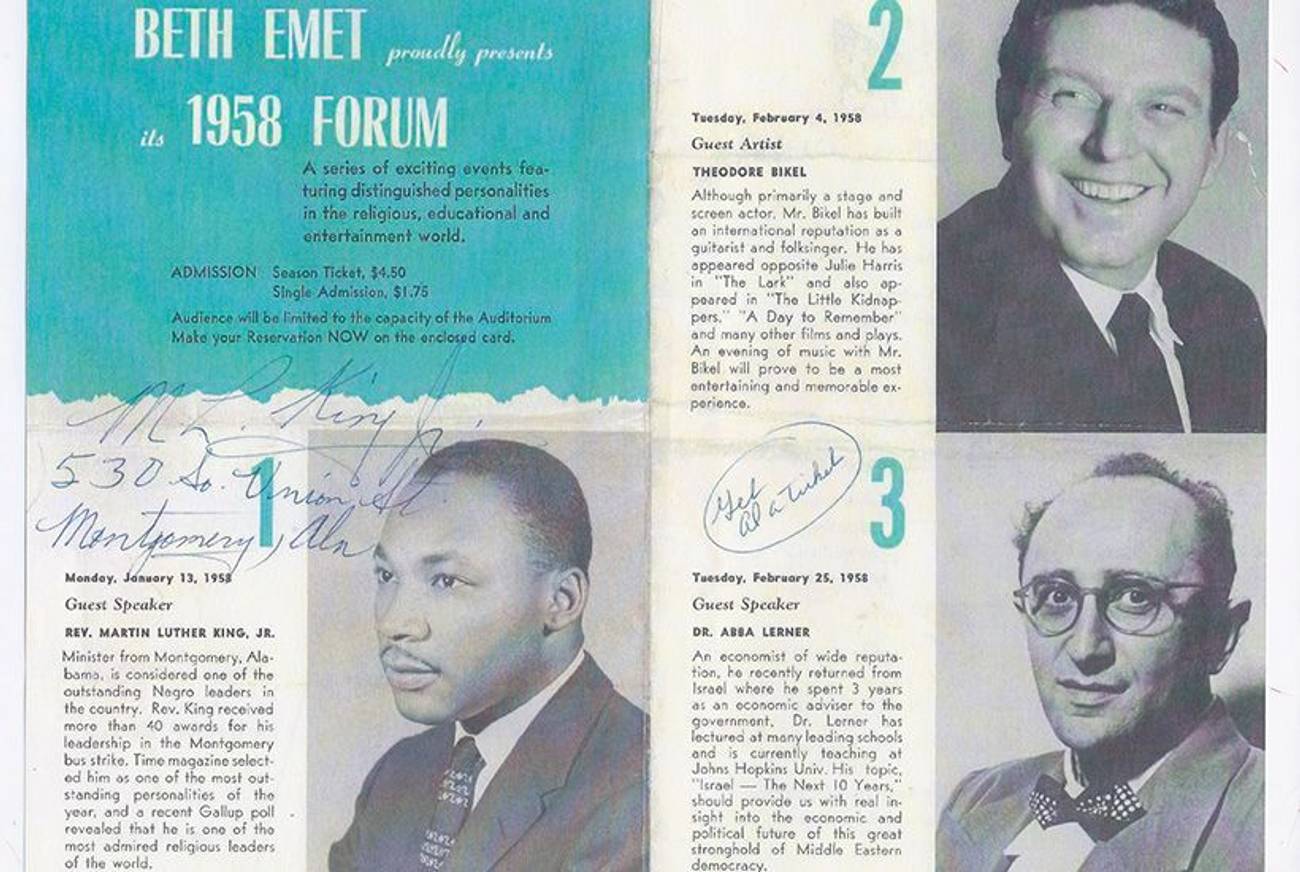

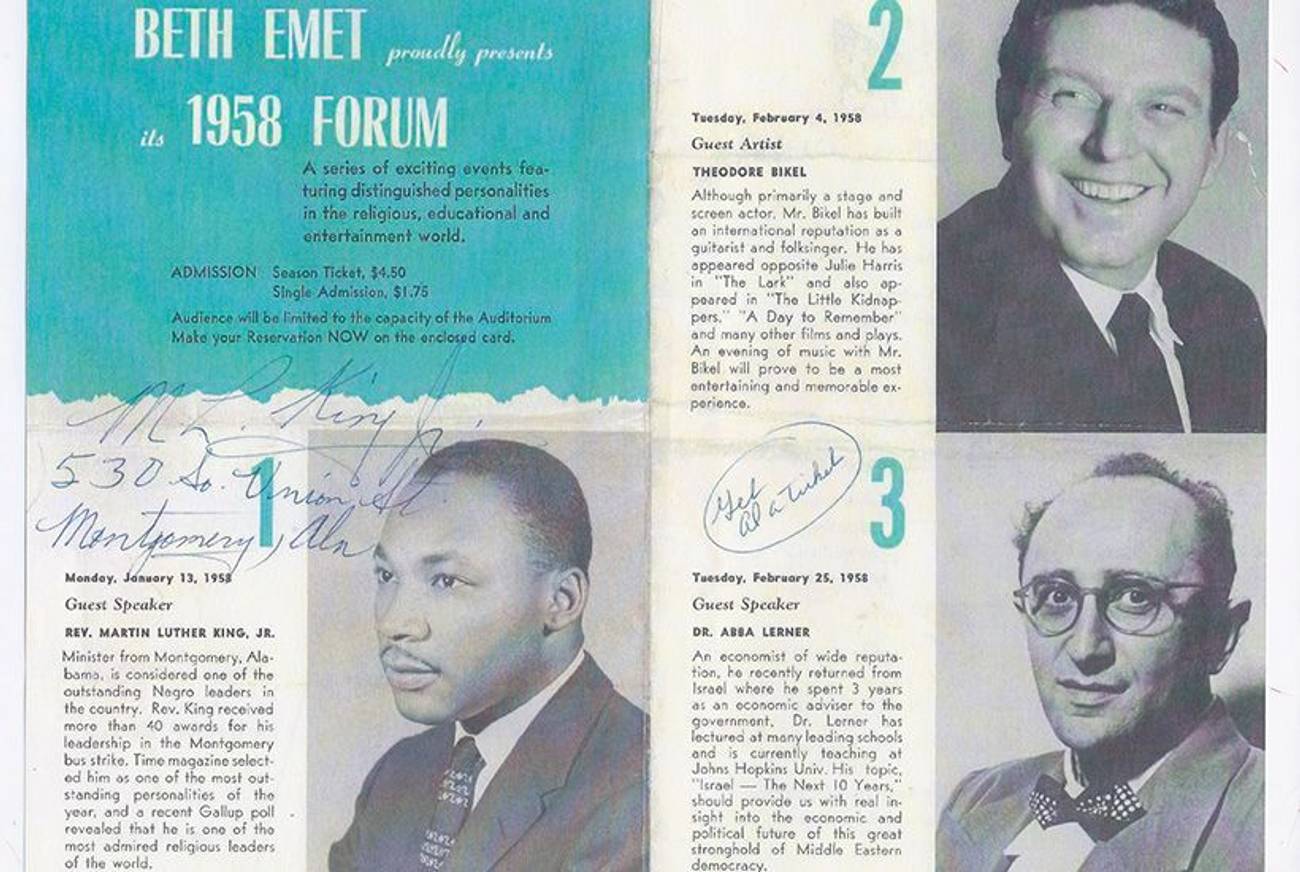

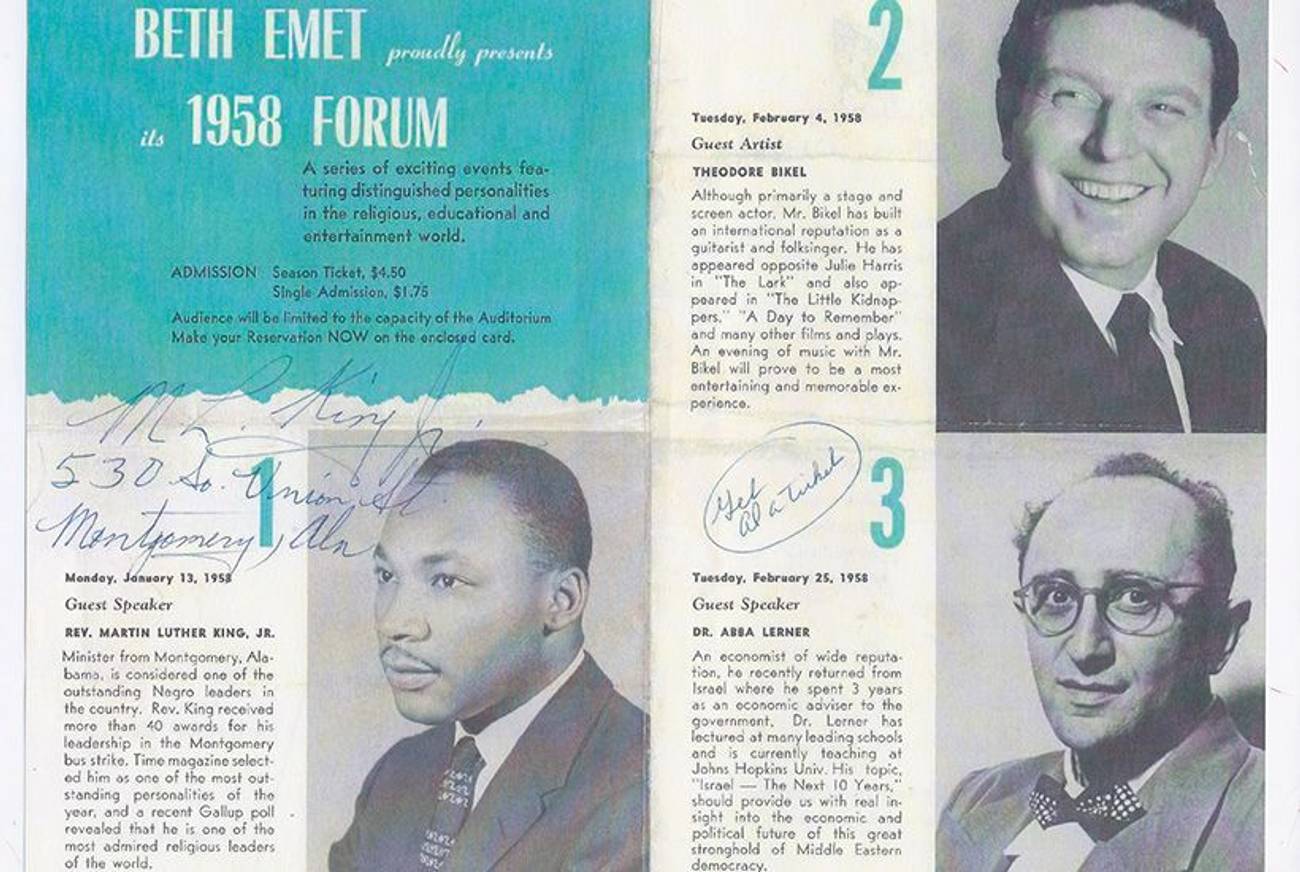

In 1958, a year before I was born, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Beth Emet The Free Synagogue, the Reform congregation in Evanston, Ill., where I am now a member. He was invited by Beth Emet’s then-rabbi, David Polish, to kick off a series of events featuring “distinguished personalities in the religious, educational, and entertainment world.” King spoke about the state of civil rights at the time, calling for social action and change. Tickets were $1.75.

Just a few years later, in 1963, the year that King made his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, my parents moved from Philadelphia to Winnetka, Ill., a village five miles north of Beth Emet. That year, a rally to protest plans for the building of a whites-only residence was taking place in nearby Deerfield. My father, a Jewish businessman who was not then affiliated with Beth Emet or any synagogue, had been moved by King’s mission to end racial discrimination and segregation. Social action was my father’s religion. He attended that rally, and for reasons likely related to giving my mother a break on a Saturday morning (she had just given birth to my baby brother), he brought me along. I was 4 years old.

The rally was held by members of the Congress of Racial Equality. According to the Deerfield Review, 50 members had marched from Morton Grove to Deerfield to Pear Tree Park, where 150 people gathered to protest the village of Deerfield, which was trying to block construction of integrated housing in the park. Clergy from the nearby Congregational Church and St. Gregory’s Episcopal Church spoke, as well as the reverend from Pilgrim Congregational Church in North Carolina. It was a mixed-race, mixed-faith affair.

I remember wondering why my father had taken me to a park, as he often did, but we weren’t near the swings or slide. Instead, my father reached for my hand and all the people there formed a circle. I looked up at him and his eyes were fixed on the crowd. A brown-skinned man took my other hand and I looked up at my father again for translation. Silence was his approval. My little-girl fingers warmed in two strong men’s hands. Then the circle began to sway and voices began to sing:

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome

Someday.

The pulse of warm palms moved through my fingers, into my arms, up to my shoulders to my mouth. The vibration of voices made my body tremble. I was transfixed. I didn’t understand why we were all together in that park, but the feeling took over. We had arrived at this park by foot and were now connected by hands and the sights and sounds imprinted on my heart as my earliest memory.

That day marked the beginning of my father’s involvement in CORE, the civil rights movement, and in Democratic politics that a few months later would land him and 35 others in a Chicago jail cell. In October of 1963, he was arrested for his part in a sit-in, protesting a Chicago School Board meeting that had included the building of segregated schools on the agenda. A photograph of my father being dragged off by police to jail made the front cover of the Chicago Daily News.

An audiotape recording of King’s 1958 speech at our synagogue was found in a congregant’s basement in 2000 and was eventually digitally restored. Here’s an excerpt.

The tape inspired Beth Emet’s current rabbi, Andrea London, to invite the clergy and congregation of the nearby Second Baptist Church to co-host the Shabbat evening before King’s birthday—a chance to listen to the tape and discuss race relations in our community today. Rabbi London and Rev. Mark Dennis designated a planning committee (of which I was a member) from both congregations and an evening of “courageous conversation” took place on Jan. 13, 2012—54 years to the day after King first spoke about racial equality in the sanctuary at Beth Emet. Several hundred people sat at circular tables that evening to talk plainly and share a meal, making King’s dream for blacks and whites to “sit down at the table of brotherhood” a reality.

That night prompted several subsequent interfaith events that included a book discussion of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander, a field trip to see David Mamet’s play Race, and a trip to see civil rights sites. Thirty-eight Jewish and Baptist high-school students, along with Rabbi London and Rev. Velda Love, a few youth directors and parents from both congregations, set out for Atlanta, Selma, Montgomery, Birmingham, and Memphis to visit civil rights sites together. When they returned to Evanston, they presented a spoken-word reflection on their experience that followed Sunday morning services at Second Baptist, and there wasn’t a dry eye in that church. On their own, the students met weekly to continue to explore issues of inequality and racism and how they might be agents of change.

That led Elliot Leffler, a former youth director at Beth Emet and a doctoral student studying theater, to spearhead another joint project: “bibliodrama” study—a role-playing, improvisational approach to the study of biblical passages, which he co-facilitated with Minister Brian Smith from Second Baptist. I decided to take part. We met every other week, all of us members of the same integrated community living within a few miles of our respective houses of worship.

One Monday evening in March, we divided into small troupes and reenacted the verses in Genesis 25 where Isaac and Ishmael reunite to bury their father Abraham. My group, which included two Jewish and two Baptist members, decided that Ishmael would have approached his estranged brother Isaac cautiously. I took the role of Ishmael, and we acted out the scene: Wordlessly, Isaac acknowledged me, and I nodded, returning his gaze. He extended his hand, holding a vial filled with perfume for sprinkling over the dead. I took it and in pantomime poured the contents over our father’s grave. I stepped back and then Isaac approached the body, unfurled a piece of fabric, and placed it over Abraham. We made eye contact and then stepped toward one another as though we might embrace, but we did not. We walked past one another and exited the room from the corners where we had entered.

The Isaacs and Ishmaels of the other two groups who were acting out the same verses made different choices about what that reunion would look like: Upon seeing one another, the brothers shook hands, touched arms, and made awkward conversation.

After our scenes, we all gathered together in a circle. Minister Smith, who had given me a big hug the week before when I’d run into him at our local Best Buy, noted that my group chose not to use physical contact for the brothers in our scene. “True connectivity needs touch,” he said. “It’s not enough to just be in the room, just to show up.” He grasped my hand and that of a Second Baptist member and talked about the role of touch in relationship building and maintenance. Then he led us in prayer.

“Let us bow our heads,” he said. “How good and pleasant when brethren, as well as estranged family, can pause to touch and realize that we are related.”

When he finished his prayer, he said with a flourish: “Now give someone a hug.” We lingered a little longer, embracing and chatting. Tears rolled down my cheeks, and I quickly blotted them dry with my shirtsleeve. I was uncomfortable at the potency of my emotions. Embarrassed. I felt as if I’d been struck by something gentle but impactful; an audible whisper to my heart.

It isn’t too often that we find ourselves standing in a circle with other people. Especially one consisting of black and white, male and female, young and old, Jewish and Baptist. Aren’t we more inclined to just show up and stand, separate from one another, in the back, to observe?

That night at the synagogue, holding hands with Minister Smith and our interfaith community, I finally understood the meaning of we shall overcome. That night had completed the circle in which I stood with my father five decades before, the one where we hoped, prayed, and sang for equality between the races, for a time when we wouldn’t have to protest for integrated housing or education. In that circle, I was witnessing some of those dreams, applied. Seeing it in practice. Jews and Baptists were studying the Old Testament, together. And we weren’t just showing up. We were interacting, like the Jewish and Baptist teens of our congregations who interacted with the civil rights sites that would no longer be mere sentences from the pages of their history texts. Sites that now had context and meaning, like the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where King was shot; the spot where the teens held onto to one another and cried.

That’s how I felt in that circle with my fellow bibliodramatists. And how I felt 50 years before that, as a protester-in-training, in 1963. Overcome.

In his midrash on Miriam’s circle dance in Exodus, 19th-century Rabbi Kalomous Epstein noted that every part of a circle’s circumference is equidistant from the center. No one person is any more or less significant in a circle. When we are children, circles are a part of our daily life—gather around for story time, children—but as we grow older, we let them go. As adults, we need them even more because a circle’s power lives in its shape; the visual reminder that human beings are created equal.

Ellen Blum Barish’s personal essays have appeared in The Chicago Tribune and Brevity, aired on Chicago Public Radio, and been heard in live lit venues around Chicago.