Montreal, Virtual Jewish Museum

A website’s interactive map brings the city’s Jewish past to life, showcasing everything from synagogues to smoked meat

Zev Moses got his big idea just looking out the window. He was living in a lovely apartment in the trendy Plateau neighborhood of Montreal and was curious to see police cars buzzing about the building next door, an ark-shaped behemoth that housed single-room-occupancy apartments populated by a different crowd than the young professionals who lived in the squat stone houses that lined the Plateau’s streets. Gazing at the building’s peculiar design, Moses realized it must, once upon a time, have been a synagogue. Having received his Master’s degree in city planning and urban design, he wanted to know more—what was the synagogue called? When was it built? Who were its congregants? But Google brought up no results.

This was Moses’ eureka moment. His neighborhood, he knew, was once littered with Jewish communal institutions, with artists and artisans, with schools and stores and factories. “And barely anyone knew where they were,” Moses said. “Suddenly, I wanted to map the whole thing and bring it back to life.”

This was 2009, and the economy was far from stable, but Moses was a man possessed. He quit his job as a consultant for real-estate developers and set about to find a way to bring Montreal’s Jewish past to life. Technology, he knew, now gave him the possibility to represent physical spaces like never before.

“Digital infrastructure has already changed the way we live,” he said. “Information is increasingly available about any object, including buildings and places. While this can be incredibly useful for running cities or running through cities, these innovations have the potential to be educational tools as well. When historical and cultural knowledge is available at your fingertips, cities become more imaginative and more meaningful places. And inevitably, as more people share information about the places they inhabit, the city becomes a museum filled with stories and experiences.”

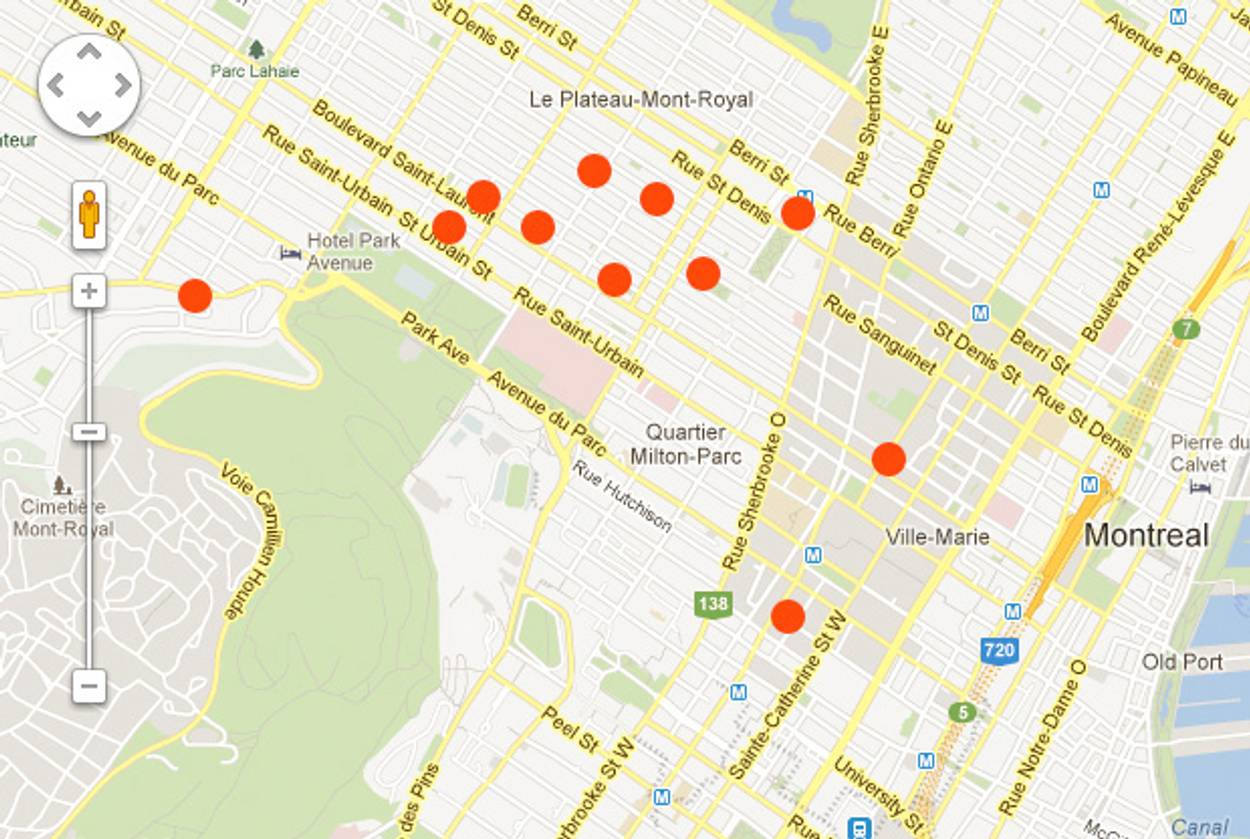

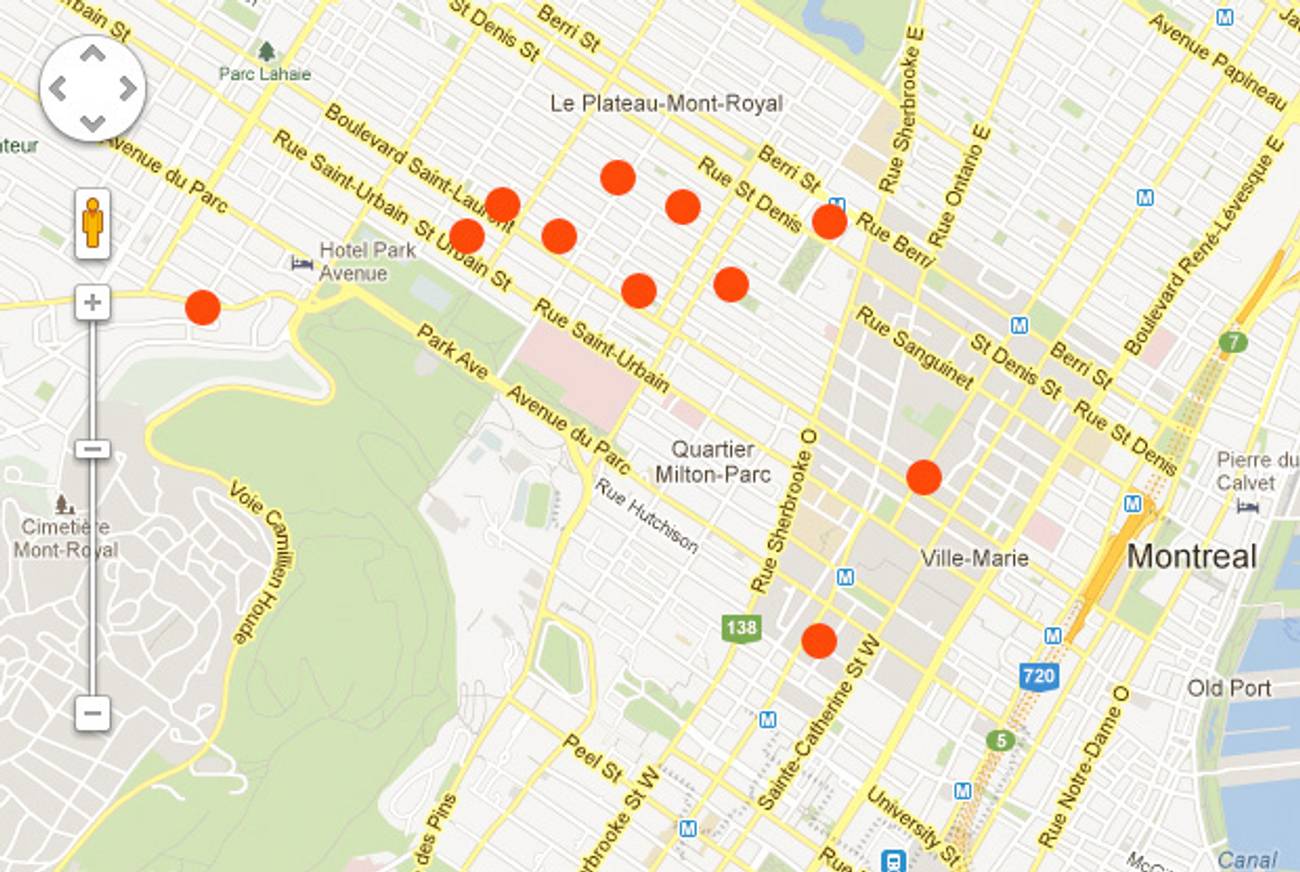

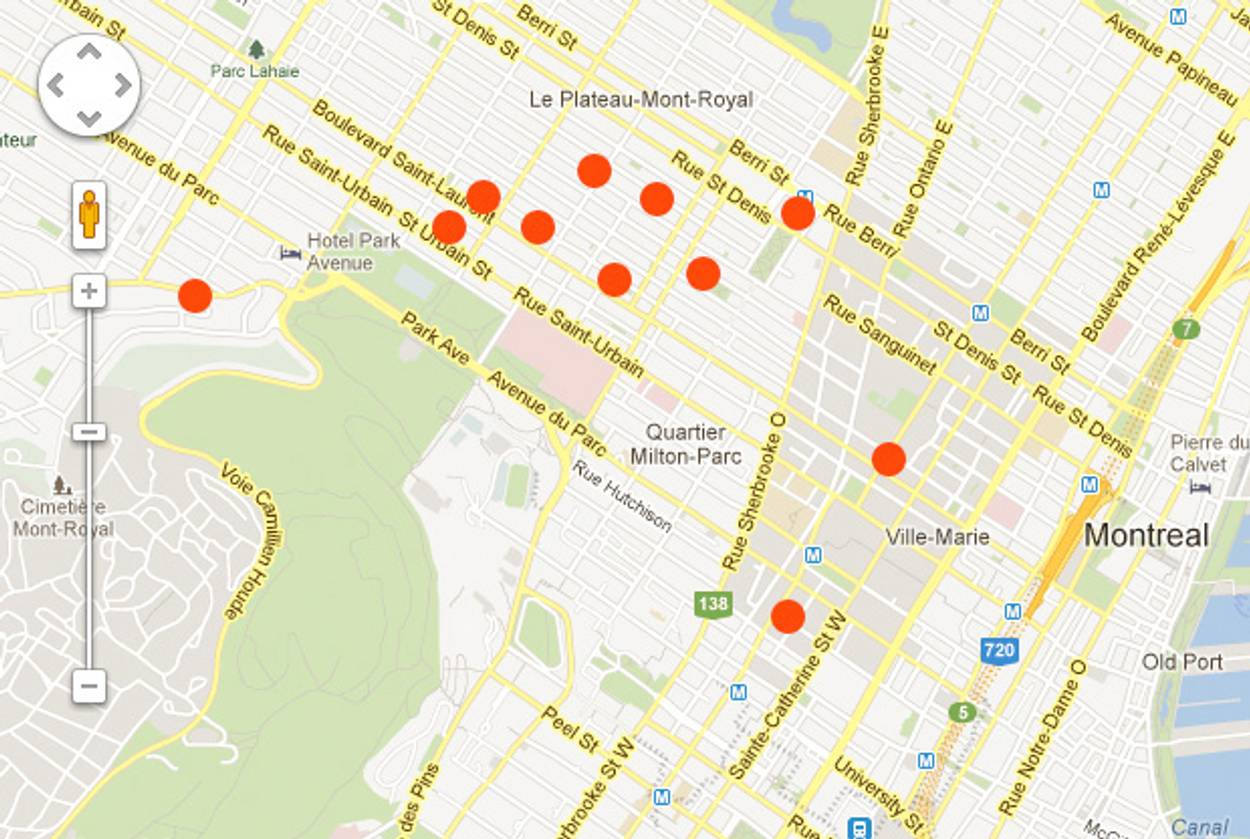

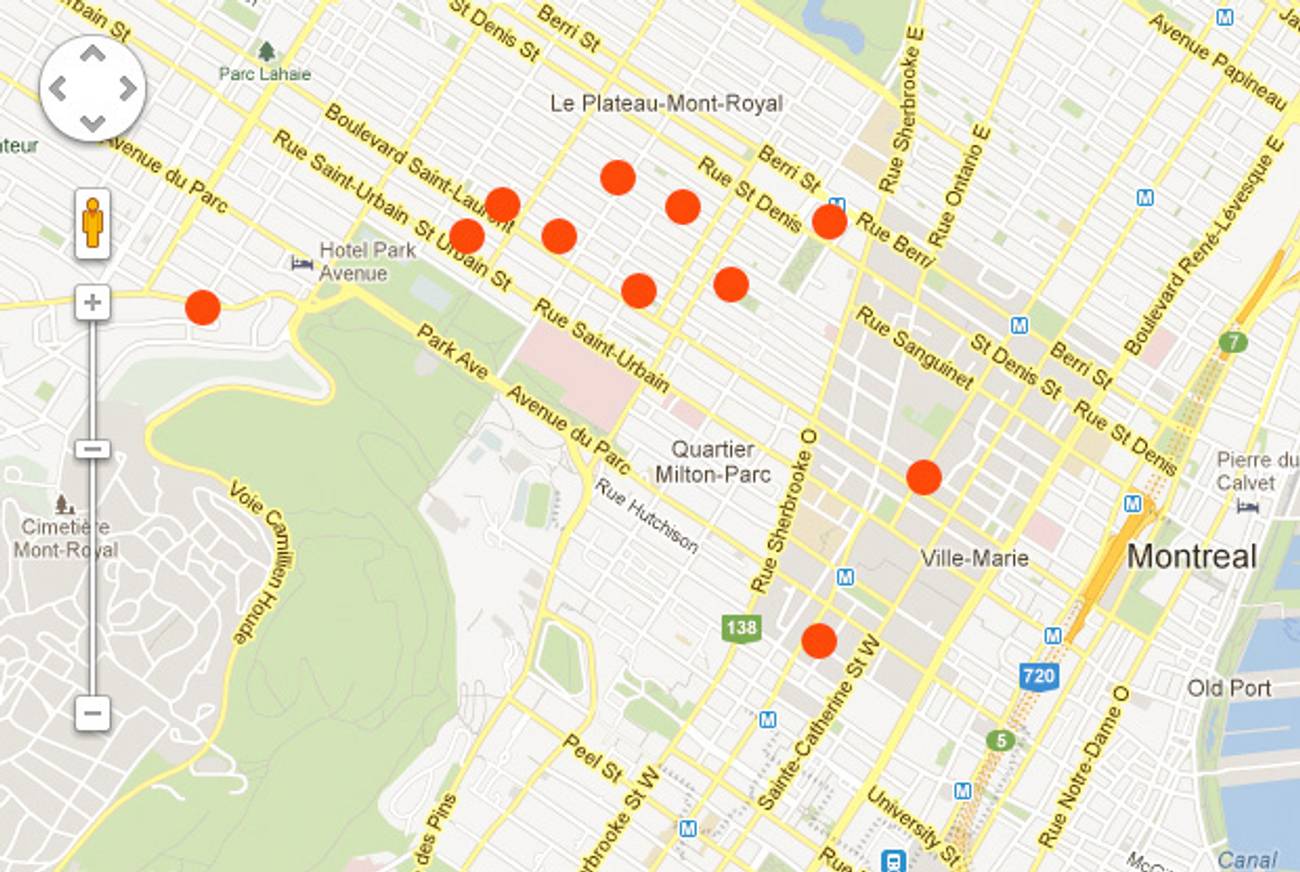

Rather than build a museum, then, with objects frozen in time and stored in a specific space, he envisioned a virtual museum that would allow anyone to look at the city’s map and see the places and the people its streets once housed. Built on the Google Maps interface, the museum—called the Interactive Museum of Jewish Montreal and sponsored by a generous grant from the city’s Jewish Community Foundation—allows its visitors to apply various filters and explore the town. One could, for example, limit a search to Montreal in the 1800s, or look only for the city’s famed Jewish eateries. Each mini-exhibit is represented by a red dot on the map; click on it, and an interactive menu pops up, giving not only a brief description but also multimedia and suggestions for further reading. This month, Moses and his partners launched their first-ever themed mobile tour, an exploration of Montreal’s cantorial tradition, which includes rare recordings and provides a snippet of what the city’s synagogues sounded like half a century ago.

“Montreal’s Jewish history is so unique and so well documented, yet it’s quickly being forgotten,” Moses said. “My fear is that in a generation, we’ll only remember bagels and Leonard Cohen.” An interactive site, he believes, is a great way to preserve this history, and a great way, too, to educate Montreal’s non-Jewish residents about their home town’s rich Jewish heritage.

Click here to visit the virtual museum, and select “editor’s picks” from the drop-down “Category” menu to see Moses’ 10 favorite spots in Montreal.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.