My Hitler Book

What am I supposed to do with it?

The offices of Mark Funke, Bookseller, are in a gray stucco building on the main street of Mill Valley, California, a woodsy little Marin County town a half-hour’s drive north of San Francisco. Redwood trees as tall or taller than six-story buildings cluster at the base of nearby Mount Tamalpais. In beatnik days the poets Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg used to hike in the redwoods on the mountain, and their buddy Jack Kerouac camped out with Snyder in a shack on it.

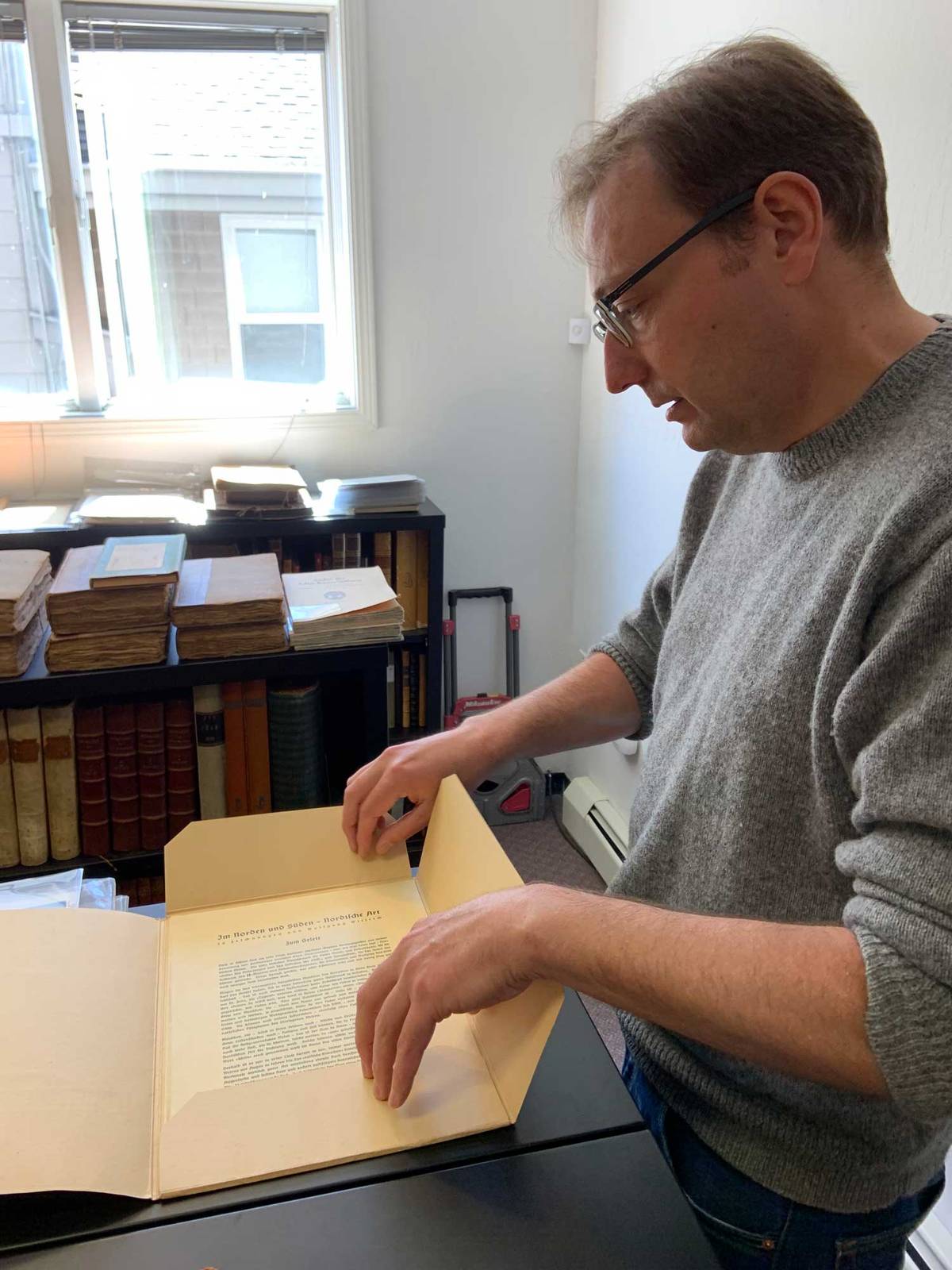

It was Sunday morning. The sky was a crisp blue and scrubbed free of clouds. I parked across the street, steered past a Pilates studio at the front of the building, headed down a short alley, and sat down with Funke—40-something, with glasses, light brown hair and a scholar’s depth of knowledge—in a small room lined with antique books that date back as far back as 1480.

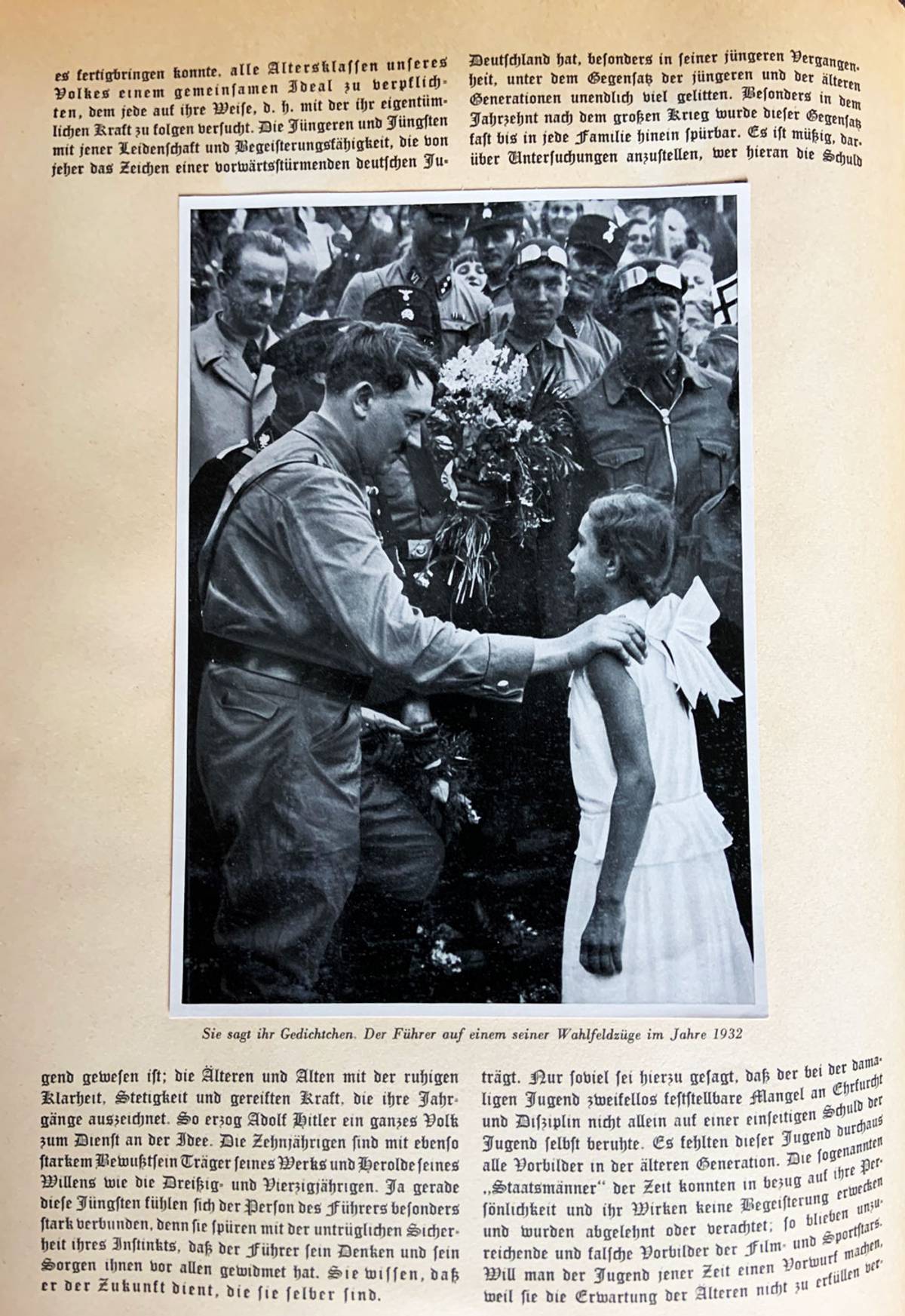

I was there to ask him to look at a book of mine, a book about a fanatical madman, one that dresses up a bloodthirsty wolf in sheep’s clothing. It is a 132-page hardcover photo album, published in 1936 in Hamburg, Germany, its text entirely in German. Its title is Adolf Hitler: Bilder Aus Dem Leben Des Führers (Pictures From the Life of the Führer). There is a Nazi swastika on the spine. Opposite the title page is a full-color painting of the Führer, one of many flattering images of the man: comforting a wounded soldier in a hospital, making nice with happy, blond children, shaking hands with a beaming factory worker, relaxing at his Berchtesgaden mountain retreat, and so forth.

Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda chief described by famed New York Times foreign correspondent C.L. Sulzberger as “one of history’s biggest and most vicious liars,” has his editorial fingerprints all over the book. He wrote the foreword and four other essays in it. Hermann Göring, the big-bellied, morphine-addicted head of the Luftwaffe, penned the dedication, and Hitler’s personal aide Rudolf Hess and other Nazi war criminals contributed literary encomiums of their own.

Funke, a former attorney turned rare book dealer who speaks and reads German fluently and who is regarded as an authority on rare European and German books and documents from WWII, was nonetheless unimpressed. He’d seen the book before. Someone even offered to sell it to him last year; he declined. Propaganda does not generally interest him as a collector or dealer, and certainly not Nazi propaganda of this kind, of which there are many copies available for sale online today.

“It was a very common household souvenir book of the time,” Funke explained, handing it back to me. “It was published by a cigarette company. Likely, millions were produced, which of course is interesting unto itself as a matter of cultural commentary. Whoever owned the book collected the pictures by buying cigarettes or groceries and they glued them in themselves. It’s very much a German thing, these albums. We have one from this period of showgirls on stage.”

When I pointed out the inscription inside the book, however, Funke’s attitude markedly changed. On a blank page in the front there is a man’s handwriting, in English. It is dated March 21, 1945, and it says: “My sons, I have formed my opinion. I hope you share the same; all through your lifetime. [signed] Your Dad.”

“Dad” wrote this and gave this book to his sons the month before Hitler stuck a pistol in his mouth and swallowed a bullet. The Allies and Russia were besieging Germany, and the Thousand-Year Reich was on its last breaths. Dad’s coy message may have been intended to mask his true feelings. Was he a sympathizer?

Funke, suddenly intrigued, thought it was a possibility. “You can’t be sure, but it sounds to me like the father was a sympathizer. Otherwise he wouldn’t be so cagey about it.” He asked with a pointed gaze, “Where’d you get this book?”

The answer to that question begins with my own father, Delmar Nelson, a WWII veteran and Oklahoma native whose early life could provide the raw material for a country song. Skinny as the handle of a pitchfork, he was the only son of Bessie Nelson, who never made it past the eighth grade but who brought her Bible faithfully to church every Sunday and was the sweetest, gentlest person you could ever imagine. They were poor and lived in farm country in the southeastern part of the state close to the Texas line. When Del was a teenager he worked in a poolroom sweeping floors and washing dishes to help support his mother. His father, Charley, robbed a train at gunpoint in Galveston during the down days of the Depression, an offense for which he was arrested and convicted. The judge let him off with a two-year suspended sentence on the promise of good behavior. Although Charley had his virtues, being a steady provider was not one of them.

Courtesy the author

At age 22, Del enlisted in the Navy after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States fully into the war. He served as a chief radio technician on a destroyer and spent time in New Guinea, Bougainville, and other island hot spots in the ferocious battles against the Japanese for control of the South Pacific. Conditions were awful—lack of food, dirty drinking water, intense heat, bugs, relentless rains, jungle fever—and at his admittance physical at the University of Oklahoma after the war’s end, he was diagnosed with diabetes, which had developed during his years overseas. The diabetes progressed over time, robbed him of his eyesight and ability to work as the managing editor of the daily paper where we lived, shut down his kidneys, and eventually killed him at age 47. They buried him, with honors, in Golden Gate National Cemetery, one of those sad, sacred grounds with row after row of white gravestones across the trimmed green grass.

At the service, an American flag was draped over his coffin before it was lowered into the ground. A serviceman in full dress uniform folded the flag in that triangular shape the way they do and gave it to my mom, who now shares that plot of earth with her husband. I still have that flag. So I guess you could say my interest in WWII is not only historical—it’s personal too.

Enter my mother-in-law, Lillian, decades after my father had passed. A warm, very bright woman with three daughters and two grandchildren, she was a graduate of Bryn Mawr who wrote her senior thesis on Cervantes after reading Don Quixote in the original Spanish. She loved reading, loved the physical book, and later in life she achieved a long-held dream of becoming a bookseller. Her bookshop in a beach town on the California coast specialized in religious literature, although in her work she came across a variety of unusual texts—one of them being the Hitler book. Knowing about my dad and my interest in the war, she gave it to me.

At least that is what I think she did. I honestly cannot remember the exact circumstances. Toward the end of her life Lillian stored hundreds and hundreds of books in her garage, planning to possibly sell them online. I may have been browsing the shelves one day and plucked it out with her permission in order to add it to my personal collection.

What a fool I was! I regretted it instantly. I hated the book and kept it hidden away in our house. I took it out to look at only rarely, usually when I was deep into a reading of Cornelius Ryan or Stephen E. Ambrose and wanted to refresh my visual memory of this “monstrous evil that threatened all civilization,” to quote another great writer of history, David McCullough. Then when I was done with it, back it went into hiding: in a closet in my office, its cover face down on the shelf, the spine turned away so that if I happened to open the closet door for some reason I would not see it.

I am more than a little embarrassed to admit all this now, except I know that other people share my misgivings about such twisted material. In C.J. Box’s 2022 murder-thriller Shadows Reel, the librarian wife of Joe Pickett, the crime-solving hero of the popular fictional series, comes unexpectedly into possession of a prewar pro-Hitler photo album not unlike mine. Marybeth Pickett gasps out loud when she opens the book for the first time and discovers its rosy pictures of Hitler and his murderous high command. When an assistant enters the room and sees her looking at it, “it felt,” writes Box, “like she’d been caught doing something dirty.” The assistant won’t even touch the book, it feels so toxic to her.

While these are characters in a novel, the feelings they feel are real. Mine were much the same. Some nights I woke up thinking about the book and what to do about it. I felt guilt and embarrassment simply by having it in my possession and further, by searching for information about it online. What would someone who didn’t know me think about that? Would they suspect that Del Nelson’s kid was secretly on the same team as the coy inscription writer? The whole thing gave me the creeps.

Courtesy the author

So much so that I considered destroying the damn thing. Not selling it, not donating it to a library, but getting rid of it, shredding it and dumping it. What harm would it do to bid good riddance to a hate crime of a book that never should have existed in the first place?

But, being a writer who had spent a lifetime chasing assignments for articles and books, nothing about that attitude felt right either. So rather than slay the beast I decided to look him straight in the eyes. This was what led me to search out Mark Funke, who, after our introductory chat in his main office, escorted me into an adjoining storage room, also filled with antique books, photographs, and documents. Among these were some very rare and very unique materials that his company had acquired in Europe and the U.S. for a catalog on German fascism.

The papers were arranged in stacks on tables in the room, each stack organized according to its subject matter. We spent probably an hour examining the pieces in each stack, with Funke explaining with admirable historical specificity the significance of what we were seeing:

Photos and signed photo cards by Leni Riefenstahl, the Triumph of the Will Nazi propagandist film director. Two original pro-Nazi speeches, stamped by the Library of Congress, seized by the American military after the war and sent to Washington, D.C., as part of the campaign to erase the stain of Hitler from Germany. Like these speeches, many of the 1 million books and papers received by the Library of Congress for safekeeping during this time were eventually surplussed and sold. An Austrian phone directory that listed only “Aryan” businesses, excluding Jews. Another phone book, this one with the names and addresses of war criminal Berlin judges whose rulings provided the legal basis for the taking of Jewish homes and property and the theft of their possessions.

“These judges were part of the structure of what the Nazis did,” said Funke. “The systemization of the darkness and destruction they caused.” After confessing my uneasiness about the Hitler book, he said yes, he got “the creeps,” too, in having to deal with some of these things. This was why his company has shifted away from WWII and was developing a catalog of far less controversial science fiction works, such as a first edition of Dune in Polish signed by the author Frank Herbert.

Even so, Funke believes the only way to come to grips with the darkness of the past is to shine a light on it. “Fundamentally I see these documents as a historical record of the past. They are challenging. They do offend people. But in the end, when it comes to history all we have are paper documents and they should be preserved. The things that people try to burn or censor today will be what people will want to study in the next century. Without them,” he added with finality, “these things will be forgotten.”

In The Book Thieves, a brilliant investigative account of the Nazi looting of libraries across Europe during the war, the Swedish journalist Anders Rydell tells the heartbreaking story of Simon Dubnow, a venerated Yiddish teacher and scholar who lived in the Baltic seaport city of Riga in Nazi-occupied Latvia. The Nazis went after anyone they perceived as their enemy. But their main targets were synagogues, Jewish libraries, Jewish homes. They stole and destroyed millions of books, diaries, letters, religious texts, scientific papers, drawings, and musical scores owned by Jews. But, as Rydell writes, the Nazis waged “not solely a war of physical extermination, it was also a battle for memory and history.” A large number of Jewish texts were taken in order to be kept in Nazi-run libraries; these would provide “the moral justification” (Goebbels’ words, from his diary) for their perverse master race ideology and barbarous regime.

The 80-year-old Dubnow was one of their victims. After raiding and trashing his large personal library, the Germans ordered him to march off to a forest outside town. Unable to walk that far due to his poor health, a Gestapo officer murdered him in cold blood on the street. At the forest where he was supposed to go, 24,000 Jews were shot and dumped into mass graves. Throughout his life, and especially toward the end, Dubnow would tell all those who lived with him in the Riga ghetto: “Jews, write and keep a record.”

This is advice for the ages, for Jews and everyone else. Keep a record! Keep those diaries and old books! And keep them safe from the fascist right-wingers and totalitarian left-wingers and bigots of every stripe. My infernal Hitler book for now remains in my possession. It is on a new bookshelf standing upright in the customary way but safely penned in on both sides by a first edition of Art Spiegelman’s Maus and the illustrated American Heritage history of WWII my mom gave to me. It’s a reminder of the shame and sorrow of how whole societies, masses of people, can be seduced by evil.

Kevin Nelson is a journalist and award-winning author of more than 20 books.