Northern Exposure

A look at life today inside Israeli communities near the Lebanese border, which have largely evacuated as tensions with Hezbollah rise

Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times

Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times

Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times

The Galilee, in northern Israel, looks invitingly lush each winter, its fields, hills, and mountains a stunning kaleidoscope of velvety green gifted by the season’s rains. It’s usually a fine time for a getaway to a national park, historical site, or B&B, with lower demand for lodging and roads less traveled.

But touring now in the Galilee is hardly ideal, with the Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah pricking Israeli communities with missiles and drones nearly every day since Oct. 8. In retaliation, the Israel Defense Forces has struck Hezbollah sites by air and artillery. Israel’s government evacuated populated northern areas lying within 3 miles of the border with Lebanon, just as it relocated residents of communities near the Gaza Strip following Hamas’ Oct. 7 invasion.

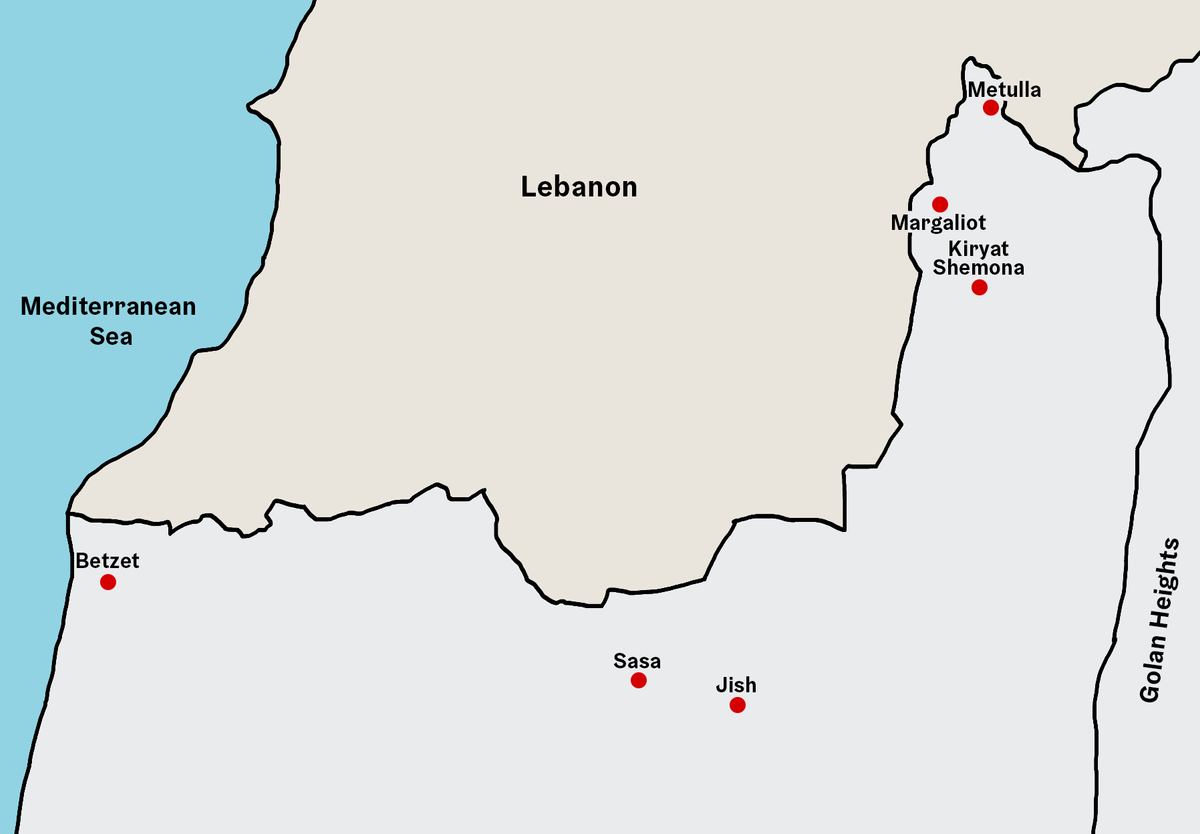

To gauge the situation, I spent two full days (Jan. 24 and 25) driving as far north as could safely be done—the IDF closed several of the northernmost roads running along the border—and visiting six diverse communities from the Mediterranean Sea eastward: two moshavim (Betzet and Margaliot), a kibbutz (Sasa), a Jewish village (Metulla), a small Christian-Muslim town (Jish), and a large Jewish town (Kiryat Shemona). Jish showed ample signs of life, while the others were ghostly deserted. Metulla and Margaliot sit along the border, requiring extreme caution to visit. In Sasa, Metulla, and Kiryat Shemona, I passed buildings struck by Hezbollah-launched missiles. I went through checkpoints on the roads and at entrances to some communities; in normal times, those checkpoints don’t exist.

Tablet Magazine

On some sidewalks and entry gates to communities now stand portable concrete bomb shelters. In three places I came upon enormous, 20-foot-high concrete barriers dropped into the lanes of main roads, zigzag style, to shield drivers should snipers or missiles suddenly threaten.

Citizens I encountered spoke of their preference to be home now. Some relocated temporarily but commute home to work, while some stayed put. Those with children said they know that normal life won’t resume until quiet is restored to their region so families can return and schools can reopen. Most interviewees said they expect some of their neighbors not to return at all.

Most posited that a full-fledged war won’t break out, but also that they wouldn’t be surprised if they are wrong—and if that happens, they said, it would result from either side making a mistake or Hezbollah intentionally escalating. Most said that they believed the situation could be calmed if the United Nations expels Hezbollah from Lebanese border villages to north of the Litani River, as Israel demands—but that such a relocation would be illusory, given the organization’s possessing long-range missiles able to reach most of Israel even from that greater distance.

Moshav Betzet

(pop. 400, 1.2 miles from Lebanon as the crow flies)

On the day before Tu B’Shevat, the Jewish holiday celebrating agriculture, Idan Ishach Erez folded the tabs of 12-ounce gift boxes for fruit her company dries and markets. Three of her workers sat at an adjacent table weighing the boxes’ contents of dried slices of peach, persimmon, apple, grapefruit, mango, banana, apricot, fig, date, and guava.

Ishach Erez, her husband, and their three children were relocated from the moshav to the Jezreel Valley in early October, putting her company, Idan Fruit, on hiatus. On Jan. 1, they made another temporary move, to Kfar Vradim, closer to Betzet, and Ishach Erez reopened the business. She drives back and forth each day.

“The new year is a good time for a change,” she said.

On the morning of my visit, the only other person I observed on the moshav’s grounds was a farmer driving an empty trailer. As if eager for company, two thoroughbreds penned at the entrance to the property followed me the length of their fence leading to Ishach Erez’s office.

Twenty minutes earlier, I’d driven north on the coastal road and encountered a sign: AREA UNDER THREAT. “There are warnings of firings,” explained a soldier at a checkpoint. I’d hoped to reach Rosh Hanikra, a kibbutz and tourist site at the border, but his words suggested caution. That’s how the trip started instead at Betzet.

Ishach Erez grew up on Kibbutz Hanita, just east of Rosh Hanikra. Her mother still lives there, but similarly was relocated in October.

“That’s what Zionism is: determining the borders of the state,” Ishach Erez said. “If we weren’t here, the area of the state would shrink.”

Kibbutz Sasa

(pop. 650, 1.8 miles from Lebanon)

For Assia Naveh, leaving home once—in 1948—was enough. Naveh was 8. She and her family left Moshav Beit Yosef, in the Jordan Valley, during Israel’s War of Independence. She remembers IDF soldiers lining the road.

Courtesy the author

“The whole matter of evacuating is difficult for me,” Naveh, 84, told me in Sasa’s library, where she volunteers. “Kids, OK. But older people: Why? There’s no reason to flee. I have very good protection: a fortified room and a shelter.”

We spoke steps from where, on Dec. 17, Hezbollah’s Russian-made Kornet antitank missile struck the kibbutz’s high school auditorium, blasting through two facing walls. Because of the evacuation, the auditorium was empty and no fatalities resulted.

The kibbutz was to have celebrated its 75th anniversary on Jan. 13. With most residents having relocated to a kibbutz near the Sea of Galilee, the event was postponed until everyone returns home, she said. About 40 kibbutzniks, like Naveh and her husband, Uzi, remain on the grounds. Sasa’s laundry, communal dining room, grocery store, and clinic continue operating to serve them, along with the soldiers assigned there and the hundreds of kibbutzniks and other workers at Sasa’s factory, Plasan, which manufactures armored plating for vehicles.

Asked why she remains in the face of danger, Naveh was nonplussed.

“I don’t feel fear,” she said. “Why do we live on the border? To safeguard the State of Israel. It would hurt to be chased from here.”

Jish

(pop. 3,300, 2.5 miles from Lebanon)

“Yesterday was scary, what with the missiles [Hezbollah shot] at the air-force radar station at Meron,” said the young woman working behind the counter at Suzana, a family restaurant in this majority-Maronite Christian town; Jish is about 3 miles from the Mount Meron facility. “Our house shook. My mother, father, and I all thought that a missile would strike the village. It was scary, of course.”

The family ran to the nearest bomb shelter.

Air-raid sirens have sounded approximately 10 times since cross-border fighting began in October, said the woman and an older man who stopped in briefly to prepare a delivery. Both declined to provide their names.

Jish residents haven’t left. “Everything will be OK, inshallah [God willing],” the woman said.

The phone rang, and she took a substantial take-out order totaling 700 shekels (approximately $190) for hamburgers, grilled chicken sandwiches, pizza pies, and bottles of soda. It was placed by soldiers stationed nearby. Two other soldiers entered the shop and perused a menu for their early dinner, too.

The town hosts an abundance of tourist sites, including an ancient synagogue. Blue historical plaques are ubiquitous on the sides of stone buildings. Cars fill the narrow, hilly streets. But visitors are scarce these days, said the man in the empty restaurant.

“People aren’t going out to eat. They’re eating at home instead. There’s no tourism. There are no tzimmers [B&Bs] open,” he said.

Business at Suzana has fallen in recent months by nearly 70%, he said.

“It’s hard. What can I do—give up?” he asked. “We’re believers.”

Metulla

(pop. 2,000, along the border)

David Azoulay, Metulla’s mayor, drove through his charming village and stopped to make a point.

“I’ll make this a hard-right turn so I won’t be exposed,” Azoulay said, referring to Hezbollah terrorists who otherwise could see the car and target it from the adjacent Lebanese village of Kafr Kila.

Why do we live on the border? To safeguard the State of Israel. It would hurt to be chased from here.

He pointed to an upper neighborhood of Metulla, now completely vacant because of its vulnerability to rocket attacks. Azoulay goes there—and to his own home on the east side of town—occasionally to check on things, but only at night and on foot, to avoid detection. Already, he said, Hezbollah has struck 120 homes in Metulla; nine of them will have to be pulled down.

Only 50 residents remain, mostly those serving in Metulla’s kitat konenut, or security-response squad. Tank treads chopped into the lawns and pavement along stately HaRishonim Street hint at the scores more soldiers now defending Metulla.

Three members of the squad huddled around a space heater in a tent at Metulla’s yellow entry gate. One, Eitan D., is an engineer who’s lived in Metulla for 30 years. He recalled when things first changed, in 2000. The IDF had just withdrawn from Lebanon, and Hezbollah’s presence caused Israel to stop admitting Lebanese day laborers through what was dubbed the “Good Fence.”

Eitan went there that day to pay a gardener his fee. With armed Hezbollah fighters nearby, he said, the gardener felt compelled to demonstrate his anti-Israel bona fides. The man refused Eitan’s cash and instead pantomimed slicing his throat.

“This situation is not normal,” Eitan said, returning to present-day tensions. “This is black and white. They want to destroy Israel.”

Kiryat Shemona

(pop. 25,000, 2.5 miles from Lebanon)

Aharon Shmuel, a mortgage adviser, told me about clients who signed a contract for a new home on Oct. 6. On Oct. 8, they and the builder agreed to put the deal on hold until tensions subside along the Gaza and Lebanon borders.

“People live their lives in the shadow of war,” Shmuel said as he dug into a plate of shawarma at Baguette Shlomi, one of just four businesses open on a three-block stretch of Road 90, this town’s north-south commercial artery.

The restaurant was by far the busiest of the quartet that afternoon, serving soldiers based in town and the few residents and workers still around. Early in the hostilities, a Hezbollah missile struck a business a few doors north, damaging the parked car of Baguette Shlomi’s owner. The family, which lives in Kiryat Shemona, was evacuated, but returns daily to work.

Shmuel and his wife also were relocated from Kiryat Shemona to the center of the country: first Rosh HaAyin, where their daughter lives, and now Tel Aviv.

“I hope that the situation won’t deteriorate [to full-fledged war]. But Israel must make sure that what happened on Oct. 7 won’t happen here with Hezbollah,” Shmuel said. “My wife is thinking that she no longer wants to live in the north. We sat in a coffee shop in Tel Aviv and saw that it’s [like being in] a bubble. I’m returning to the north, no matter what, because I love the north. The center is too busy. The north is green. Plus, I love the people here. Everyone knows everyone.”

Their 6-year-old granddaughter, Noa, generally looks forward to coming to Kiryat Shemona every two weeks and spending the entire summer here. She recently told them that she misses visiting.

“She asked to see a picture of our home,” Shmuel said. “It was sad.”

Moshav Margaliot

(pop. 440, along the border)

When not raising eggs produced by his 4,000 chickens or farming 35 acres of peaches, apricots, nectarines, cherries, and plums, Yoni Yaakobi serves on his moshav’s kitat konenut.

Agriculture and security are intertwined in this mountaintop community. As we drove to his home on Thursday evening, Yaakobi stopped to offer a glance backward. The lights shining from a higher ridge were Markaba, a Lebanese village just 300 yards away.

Courtesy the author

Ten of Yaakobi’s acres are inaccessible, he said, because Hezbollah fighters are positioned smack on the other side of the border fence, just 20 feet off. The situation being what it is these days—tense—he’d make an easy target, Yaakobi said.

Fellow farmers on the moshav are considering retaining their operations while living instead in Tiberias, said Yaakobi. That’s not his way. Similar to Betzet’s Ishach Erez and Sasa’s Naveh, Yaakobi sees his presence as safeguarding Israel’s hold on the frontier land. Only 15 moshav residents remain in their homes. Most others were relocated to the hotel at Kibbutz Lavi, west of Tiberias. Yaakobi and his wife joined them initially, but now are back.

“I’m here, first of all, because I believe it’s forbidden to leave home. If we were not here—I, and Misgav Am, Metulla, Zarit, Shtula, Dovev, Avivim—they [Hezbollah] would be here,” he explained, mentioning other Galilean border communities. “It’s the idea of Eretz Yisrael. Israel was purchased with blood, unfortunately.”

We said goodbye so Yaakobi could meet with a security official. The next morning, Hezbollah launched a missile that fell in a field on the moshav. Yaakobi shrugged it off.

I called again on Monday afternoon, Jan. 29. Three new missiles had just fallen.

Hillel Kuttler, a writer and editor, can be reached at [email protected].