Nova Massacre Survivors Retreat to Cyprus for Healing

‘These kids are not in post-trauma—they’re in trauma’

David Vujanovic/AFP via Getty Images

David Vujanovic/AFP via Getty Images

David Vujanovic/AFP via Getty Images

As Maya Peretz entered a sunny room for an art therapy session on Dec. 26 and took a seat, someone asked her about a party the previous evening.

“I didn’t go because I’m in mourning for my father,” Peretz responded, referring to the Jewish tradition of refraining from celebrations during the 12 months following a loved one’s death. “I just sat outside and smoked.”

On Oct. 7, Peretz’s father, Mark, also known as Mordechai, sped from the family’s home in Rishon LeZion to the site of the Tribe of Nova music festival, an event Maya—a French dual citizen who works in a shoe store—was attending to celebrate her recent discharge from the Israel Defense Forces. He was determined to rescue her after learning of Hamas’ mass infiltration from the Gaza Strip. Near Kibbutz Mefalsim, just north of his destination, terrorists murdered Mark in his car.

While she explained, Peretz selected a brush, dipped it in a cup of water and containers of paint, then dabbed it onto a paper, forming images of cherries and leaves.

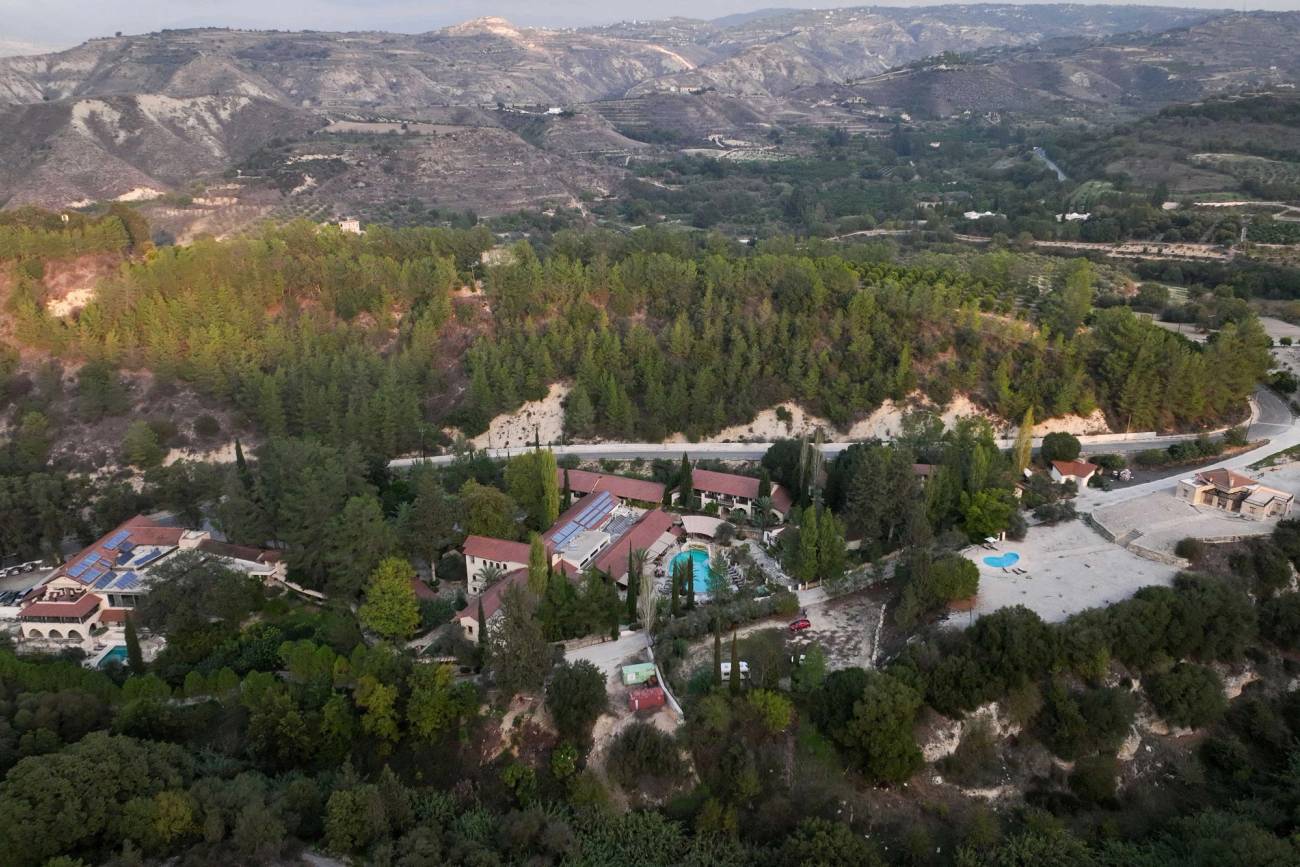

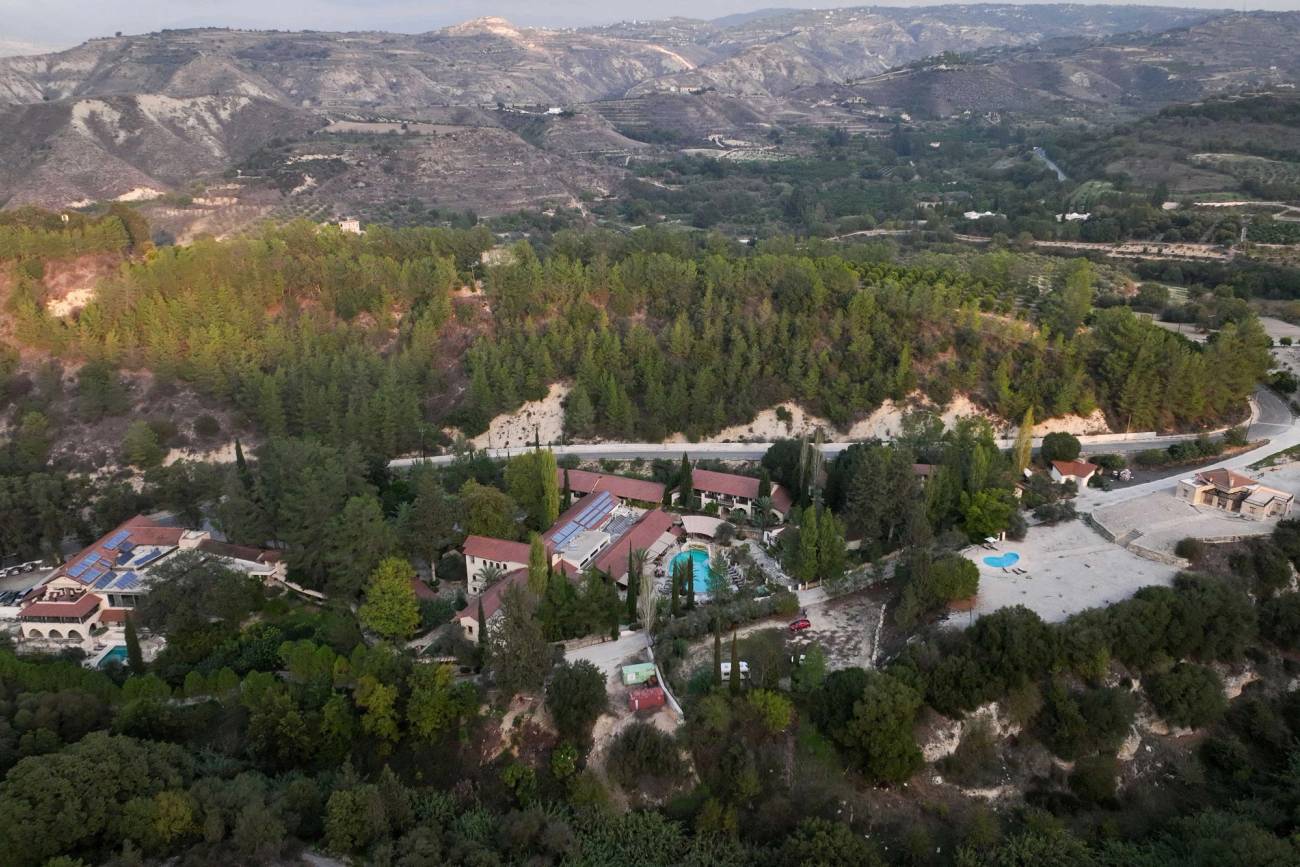

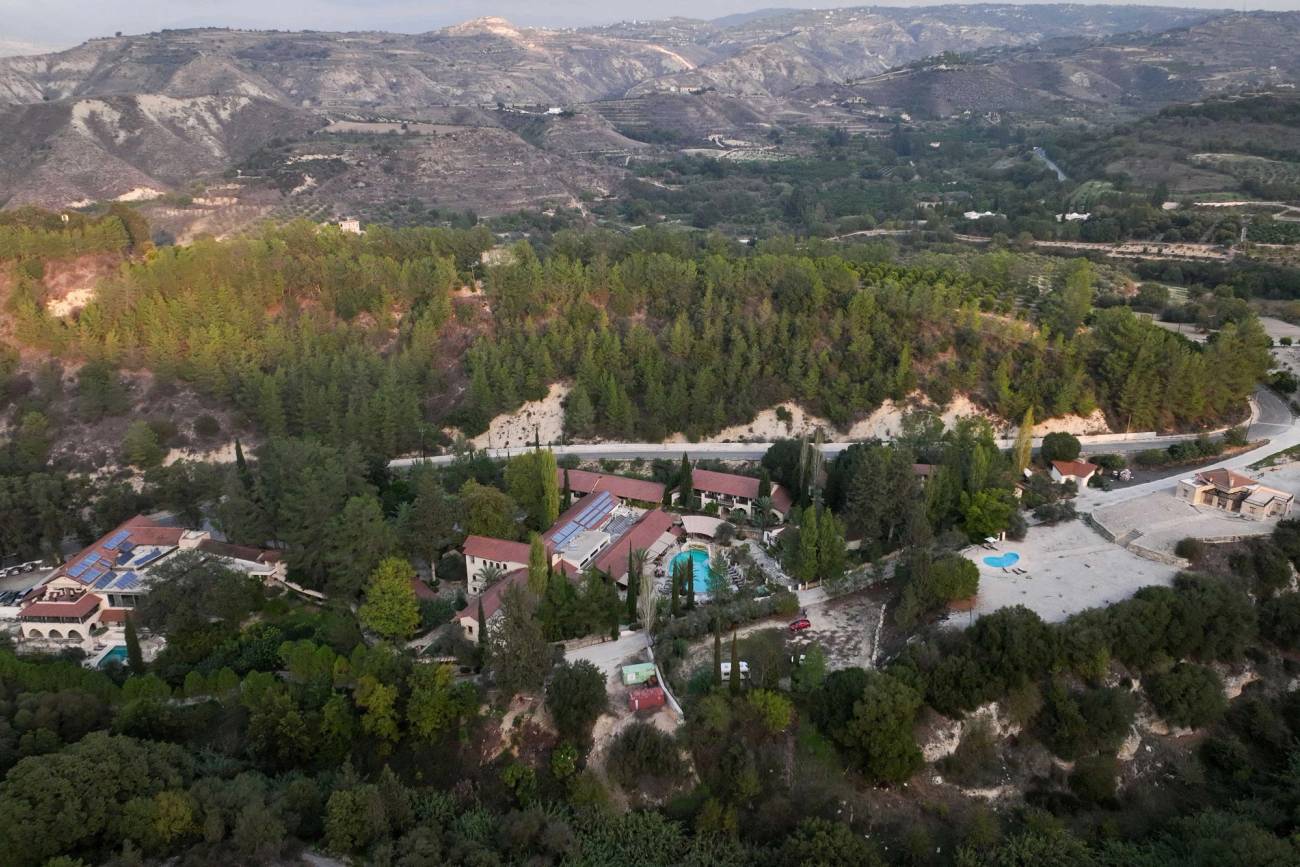

This scene transpired about midway into a five-day retreat at a spa in the mountains of Cyprus for 70 Israelis who, like Peretz, had survived the Nova massacre. Of the 1,200 people murdered and 240 people kidnapped in Israel that day by Hamas, 360 and 43, respectively, were at the festival.

The retreat I visited was the 10th such gathering for Nova survivors at the facility in Cyprus, known as Secret Forest. Five weekend programs also have been held there for bereaved parents who’ve lost children: those who fell in battle during Israel’s ongoing war with Hamas or were murdered at the festival or in the ravaged communities near the Gaza Strip.

Hosted every week since Oct. 22, the Nova-survivor retreats were conceived by Yoni Kahane, an Israeli hotelier who opened the spa in January 2023 on leased property north of the resort town of Paphos.

Kahane got the idea after reading about a Nova survivor sequestered at home, depressed, lacking a will to live.

“I said, OK, that’s what we need to do: Bring people here, give them a hug, fortify them, encase them, give them rest for the body and soul, mental healing with staff who will embrace them, where they’ll be with those like themselves in a cycle of discourse and sharing and talking and dismantling and unloading,” said Kahane. “We felt we had a mission to care for our people.”

Approximately 1,700 Nova survivors—more than 3,500 attended the festival—have registered to attend the retreats, he said. A Tel Aviv-based nonprofit organization, IsraAid, is covering most of the expenses through January. Each participant pays about $385 for the flights and land transportation.

Courtesy the author

Those attending the late-December retreat could go to workshops on self-healing, self-image, inspiration, and survivor’s guilt; participate in meditation and yoga classes; relax in pools, hot springs, and a sauna; get a massage or acupuncture; walk in the surrounding forest; sit around a campfire; or borrow bicycles. Lavish kosher meals heavy on salads and fish were prepared, and soup was served during afternoon breaks. The only required attendance was a 90-minute group session each afternoon: nine people each in eight groups, all led—as were the workshops—by Israeli therapists who volunteered.

As she painted, Peretz told of running a great distance to escape Hamas’ carnage before someone drove her to the town of Ofakim. She spoke softly in the nearly deserted room. The resort’s dining area had been starkly empty during the just-concluded breakfast as partygoers slept off fatigue from reveling past 4 a.m. the previous night.

A few hours after the art class, Peretz revealed more to her group therapy session: Her brothers and their paternal grandmother blame her for Mark’s death. Had she not gone to Nova, they charged, he’d still be alive.

Guilt—along with fear, helplessness, loss, and anger—was among the prominent emotions and feelings that mental health professionals at the retreat helped attendees to process. Pervading all was trauma, several therapists said in interviews.

It was palpable even to some of the spa’s guests who hadn’t come for the retreat.

“These kids are not in post-trauma—they’re in trauma,” said Idith Shukron, a vacationer from the Tel Aviv area who met some of the Nova guests. “They’re still in the process.”

Nova survivors seemed ambivalent about sharing their insights for this article. Within hours of arriving, two women expressed a willingness to discuss their experiences, but repeatedly thereafter said they were busy. Another woman answered questions, then stopped when asked her surname. One man agreed to be interviewed, subsequently demurred several times when approached to sit down for the interview, and ultimately spoke on the record. Four others in separate conversations provided their names, spoke for a moment or two, excused themselves, then disappeared.

Opening up to outsiders isn’t easy for some Nova survivors. Therapists leading the group therapy sessions offered one-on-one meetings on-site, with some taking them up on it. After everyone returned to Israel, follow-up includes referrals to other therapists and drug and alcohol counselors.

Conversing informally with each other, even those newly met, and in group meetings, came easier—among the aims of the retreat.

“At home, I’m the deviation. They look at me strangely,” one woman named Nicole told other attendees at the survivor’s guilt workshop. “It normalizes me to be here.”

One of the therapists, Orna K. (she requested that her surname not be used), asked for an example.

When I go to sleep, I see terrorists.

Nicole said she posted of exercising at a gym. “Someone wrote [in a comment], ‘So nice to see that you’re back working out and didn’t suffer too badly,’” she said.

“How can someone you know and are close to say that—that if my body is OK, I’m fine? I wrote back, ‘When I go to sleep, I see terrorists.’”

A male participant interjected: “People say, ‘Don’t get depressed.’”

“I hate hearing that,” Nicole said.

At another point in the session, Orna pointed attendees to two tables containing art supplies and suggested that they depict survivor’s guilt. “Put a color, a size, a texture, a shape to it,” she said. “Use the scissors and the glue.”

A buzz enveloped the room as some participants got to work. During the break, I chatted with Motti Gallam, one of the social workers. This was the third retreat he’d worked.

“You think that worse than this you won’t hear—and then today I heard a girl tell how she used the blood of her murdered sister, next to her, to paint her own face so that she’d appear to be dead,” he said.

Orna instructed those who finished their art projects to place them on the floor in the center of the circle where everyone sat. Five people did so. She requested that they explain aloud what they’d created.

Tal Rolland, 24, from Netanya, had used crayons to draw a black satchel labeled GUILT that, when lifted, revealed a red rectangle representing her smeared blood. She’d glued the satchel onto a heart she drew. Falling onto the heart were vertical lines made by brown and yellow crayons: strands of Rolland’s hair.

“The whole world should see what I feel,” said Rolland. Two of her friends from Karmiel arrived at Nova just 30 minutes before the terrorists attacked; both were murdered.

When the session ended, I retrieved Rolland’s work from the floor and approached her to ask about it. I returned the drawing to her. She refused it.

“You take it,” she said. “You’re a journalist. You can circulate it in the world.”

The December retreat came during a time of intense examination in Israel of the Nova experience. Two documentaries had just premiered on a major TV station: one consisting of interviews of a few survivors, the other of footage survivors recorded on their cellular phones while fleeing and hiding. A Tel Aviv conference center this week extended its exhibition of the Nova setting, complete with tents, one of the bars, clothing, backpacks, and bullet-ridden portable toilets and vehicles. Visitors could retrieve items they saw that belonged to themselves or a loved one.

The interest in Nova likely derives from the “extreme contrast and polarity” between “young people celebrating life who found themselves in a death field,” said Yaron Ziv, one of the therapists brought to Cyprus.

As he welcomed his nine charges to the first of three daily group therapy sessions, held in a villa a short walk from the spa, Ziv played “Say Yes,” a song by an Indian therapist named Veeresh.

Everyone was standing in a circle in the villa’s living room. Ziv instructed them to close their eyes. As the song’s opening notes played, he told them, each time they heard the singer say, “Just say yes,” to add the words “to life.”

“It’s not taken for granted,” he said.

When the song ended, Ziv told them to keep their eyes closed, tighten the circle, and hold hands.

He then played another song, a prayer Jews utter during Friday night services.

Without prompting, the circle of people hummed along.

“Hear our cry, thou who knowest secret thoughts,” it ends.

Courtesy the author

Ziv told them to open their eyes. He uttered a phrase in Spanish: “The eyes are the window into the soul.”

He divided the nine into three groups of three, telling them to again close their eyes and connect to their feelings since arriving in Cyprus.

“Now, lock in on one thing carved into you since Oct. 7, something you can’t stop thinking of, like people or friends killed or kidnapped, that if you could let it go, you would. Each of you displayed amazing strength to survive. What strength you exhibited! You said, ‘I won’t give up. I’ll stay with it. I’ll run 20 kilometers.’ Now, open your eyes and tell each other what you locked in on.”

In a conversation during a break in the session, Shaked Halfon, 25, from Ashkelon, said she’d related having escaped the massacre by car, ditching it amid a traffic jam leading to Route 232 at the outskirts of the grounds, running to an adjacent field—while on crutches due to CRPS—and hiding for eight hours in a bush. She heard terrorists speaking in Arabic. Bullets flew by.

The day she arrived in Cyprus, Halfon was to have begun law studies in a semester whose start was delayed more than two months by the war. The retreat took priority, she said. Halfon spoke of becoming anxious when caught in a bottleneck or watching someone run by, regularly feeling afraid and hopeless, and not sleeping well—a university study she’s participating in found that she awakens about 27 times nightly. She displayed a picture on her phone from the morning of the attack, showing an ambulance as it idled in front of her car. The ambulance couldn’t evacuate wounded concertgoers.

Halfon took leave from her job managing a restaurant. She was having far less patience for customers’ complaints—“stupid things,” Halfon said, that she’d have resolved previously, like food being unsalted. Even while hiding on Oct. 7, Halfon said, she read a coworker’s text stating she wouldn’t be coming to work that morning because of Hamas’ missiles. Halfon dismissed it as wildly unimportant.

“We are in an event that hasn’t yet ended,” she said. “What brought me here was the need to disconnect. I’m here in isolation, in quiet.”

After dinner that night, Ido Malik, a 28-year-old from Haifa, said he, too, suffers from sleeplessness, consistently experiencing nightmares of terrorists chasing him. He’d gone into therapy, tried acupuncture, then heard of the retreat. On this morning, his first full day at the spa, he went to the yoga and meditation classes and relaxed in the hot springs.

The Cyprus retreat “is another avenue” for recovering, he said. “Coming here, away from Israel, helps me. It helps my soul to breathe. Speaking about it helps,” he said. “Even this interview helps. You’re doing a good thing by telling people about this. They don’t know.”

Malik and a friend beat a hasty retreat after the music at Nova ended when Hamas launched thousands of missiles on Oct. 7. But their car, too, couldn’t get past the others. A driver three cars away screamed about terrorists firing up ahead. Malik made a U-turn and drove, then the two got out and lay under the car. They saw people being shot to death meters away. When the shooting became more sporadic, they ran to a 13’x13’ wall and hid behind it for 90 minutes until being rescued.

“You don’t feel fear or consider what to do—just operate on instinct. I’m happy I had that impulse to survive. Maybe that came from [serving in] the army, but not only,” he said.

Malik’s job involves canine therapy. When he returned home that night, Messi, his Labrador mix, “noticed my negative energy,” he said. “Instead of jumping on me, he was subdued. I lay on the floor, and he lay on top of me.”

At the start of his second group therapy session, Ziv spoke about the bonds Nova survivors—much like ties between any survivors of trauma or other profound experience, like war combat—share.

He also raised a theme that Nova survivors no doubt ponder endlessly: why they emerged from the hell while others didn’t, how instant calculations made under intense pressure might have saved their lives.

“Think of the split-second decisions you made: to turn left or right were life-and-death decisions, to stay in the car or abandon it and run,” Ziv said.

It’s something a Nova survivor, 26-year-old David Bromberg, touched on during an interview that day.

“The people you see here, whatever choices they made, even if they were stupid, were the right ones, because they survived,” he said, mentioning his own right-and-left turns, literal and figurative, on Oct. 7. “Every point led to me being alive.”

Then there was luck. Fate. No reason to have lived through the carnage.

Courtesy the author

Ziv mentioned his own good fortune. His son Assaf, 26, reached Nova at about 4 a.m. that fateful morning, but left an hour later to return home because of severe abdominal cramps.

Had Assaf not gotten sick, Ziv might have found himself in Cyprus not as a therapist but as a participant in the bereaved-parents group.

In the Nova group, a woman named Maya (not Maya Peretz) told of her own dumb luck, which she still struggles to process.

It involved terrorists passing close by, and resolving that her life was about to end.

“I understood that I’d be killed—and, voila, I was alive,” she said.

A resident of Ramat Gan, Maya said she completed her degree in interior design and worked in her field. She enjoys dancing, listening to music, sewing—or she did prior to Oct. 7.

“I don’t have the strength to do my hobbies, to make a nice breakfast,” she told the group. “It’s the time to do these enjoyable things, and I can’t. It’s hard.”

As she hid in the bushes for five hours amid the slaughter all around her, Maya said, she kept looking at a bracelet she’s worn for two years, wondering if it projected her surviving or, rather, being murdered. She raised her wrist before the group.

“Everything is intentional,” the bracelet reads.

She cried.

Ziv invited the others to chime in. One man, Maor, related that he, too, lacks the strength for even rudimentary activities in the morning. As the day wears on, though, energy comes. He’ll start with a hot shower, then prepare a good meal.

“Let it occur slowly,” Maor said to Maya.

Ziv seized on the point.

“You can’t rush things. It’s not too early or too late. It’s your reality. Planting and flowering never occur at the same time. You plant, you wait, and it flowers. There’s a ripening. People who weren’t [at Nova] will say, ‘When will it be over?’” he asked, referring to emotional recovery from the trauma.

“There’s no such thing,” he continued. “Everyone needs his time. Everyone needs his ripening. The best medication is to say: There’s no set date.”

Hillel Kuttler, a writer and editor, can be reached at [email protected].