On Being Prepared

How I found myself—and my Jewish identity—in the woods of Tennessee

I had my midlife crisis at 15. It seems silly, thinking about it now, but at the time I couldn’t conceive of living much past 30. Growing up and growing old, I figured, were delicate pursuits best attempted in happy homes, and mine had just fallen apart. My father in prison and my mother working several jobs to make ends meet, I had a lot of time on my hands, long stretches of late afternoons and early evenings that my friends spent standing with their parents in the kitchen, talking about their day or helping out with dinner. And because I was too overwhelmed by my own emotions—rage, mostly, but also specks of self-pity and, sporadically, profound doubt that the very project of existence was worth the trouble—I naturally gravitated toward distractions that let me travel outside of myself. Drugs were amusing for a while, and sex was always fun, but, eventually, I settled on scouting.

At first, it was almost a perverse pleasure: Walking into my local troop with my platinum-blond mohawk, my tattoos, and my calamitous attitude seemed like yet another way of howling at the moon. I’d waltz in, I thought, shock the squares, and get still more confirmation that I really didn’t fit in anywhere and was destined to perish soon and without causing much of a stir. God and the scouts had other ideas: They handed me a crisp khaki uniform, a pocketknife, and an invitation to spend the summer in the woods. I did, and reemerged the sort of guy who could tie a square knot with his eyes closed, knew that moss always grew on the north side of trees (or the south, depending on the hemisphere you’re in), and found his way around at night just by peeking at Polaris. These were good skills to have, and they filled my days more constructively than bourbon ever could, but they did not make me into a man. For that, I needed Saba.

I first spoke to him on the phone from the Israeli Scouts’ central office in southern Tel Aviv. Even though I had only been a scout for a little less than a year, I was selected to represent the movement on a three-month delegation to the United States. I was thrilled at first—three months away from home, away from those languorous afternoons, was a godsend—but then crestfallen: The other scouts, I learned, were all being shipped off to large and well-established Jewish summer camps, while I and another, a bright and soulful young woman named Efrat, were going to Memphis to do something else. What exactly? Saba, we were told, will explain everything. But when they rushed us to the phone to speak to this mystery man, we understood very little.

I mean that literally. Saba spoke in the kind of Southern drawl that came at you like a lake, smooth and slow and easy until you were deep enough in it to realize that it commanded you and not the other way around. I asked no questions, and Saba provided no details. He’d see us soon enough, he said, and will tell us everything we needed to know then.

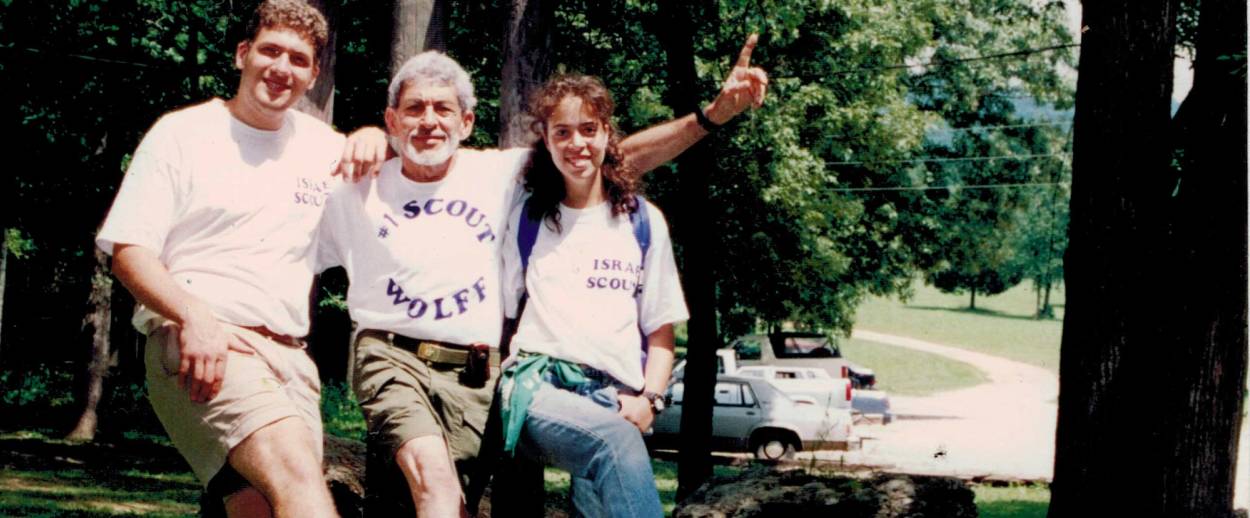

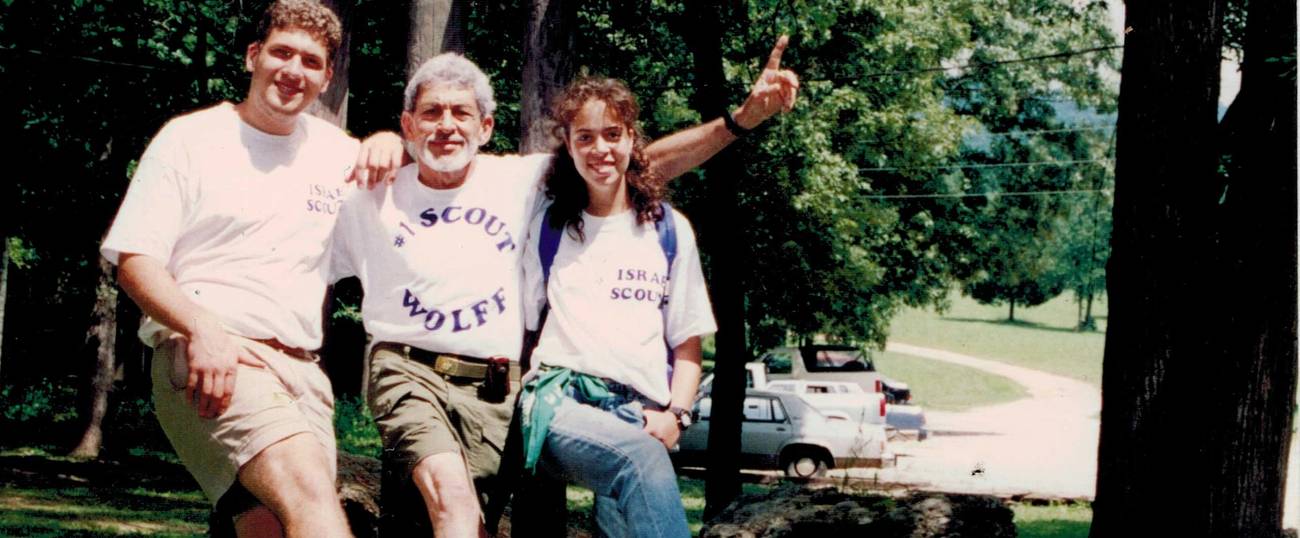

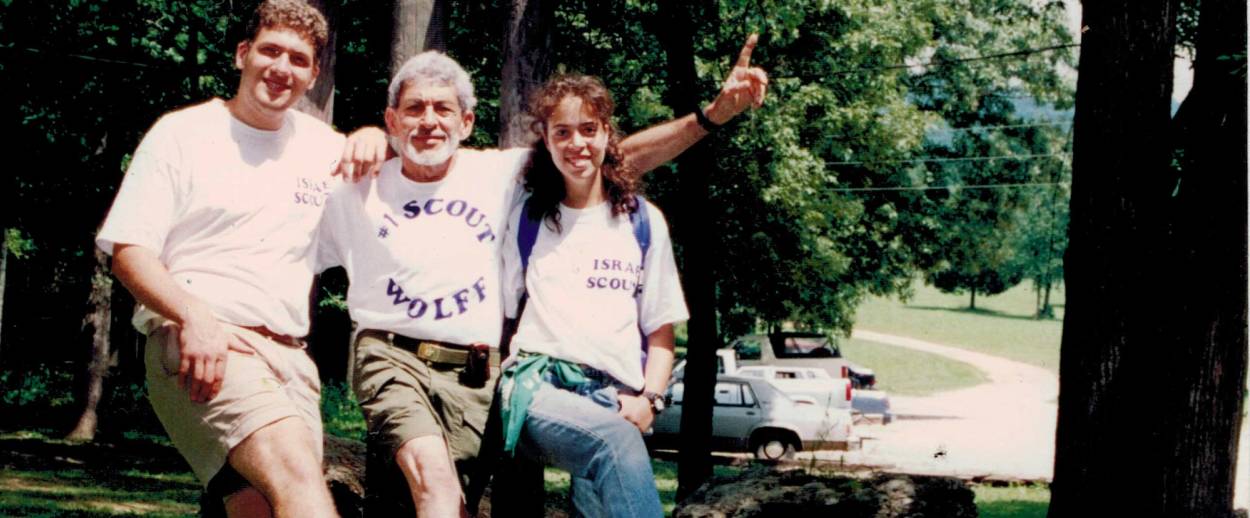

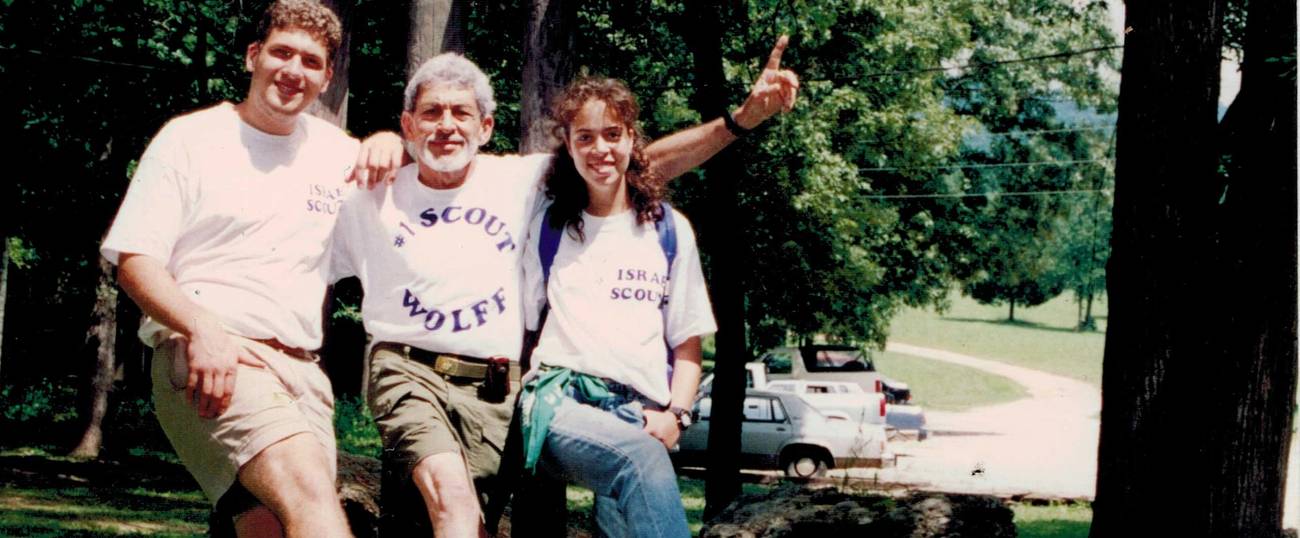

What did the man from whom that voice issued look like? I pondered that question on the flight from New York to Memphis, and because my ideas about the South, like my ideas about much of the rest of the world, came from American TV, I decided that a persuasive Southern gentleman with means—flying two Israeli scouts over for the summer couldn’t have been cheap—must be the twin of that Dallas eminence, J.R. Ewing. Waiting for us at the airport, however, was a smallish man with a white beard, well-worn jeans, and a do-it-yourself T-shirt that read “#1 Israeli Scout.” If J.R. had a guy washing his Cadillac Allante, Saba looked like that guy’s grandfather. At least the nickname he’d chosen for himself, Hebrew for grandpa, fit the bill.

Because he was not the kind of man who was very good at keeping things to himself, we learned everything we needed to know about Saba right away. His real name was Art Wolff. He was born in Cincinnati and served in the Air Force. He had done well for himself in real estate, but his own home was just big enough for a man who knew well that his true worth had nothing to do with the value of his properties. He was a passionate environmentalist who shared none of the breed’s habitual aloofness: When developers proposed a road that would run through his beloved Shelby Farms, one of the largest urban parks in the country, he opposed it so forcefully, so frequently, and so effectively that even today, 30 years later, the plan is still nowhere near fruition. He’d succeeded because he thundered on in a voice he’d borrowed from higher realms: Like Dr. Seuss’s Lorax, whom he resembled physically and psychically, Saba saw his role, his daughter later recalled, as “being the conscience, the thorn in your side.”

He was often the thorn in mine. Efrat, who was smarter and kinder and better-adjusted, embraced Saba’s stubbornness; I mistook him for yet another adult to mistrust and defy. He insisted that we wear white T-shirts with huge smiley faces emblazoned on the front and big, blue lettering that identified us as scouts from Israel; I thought that was tacky and mortifying. He arranged a hectic itinerary for us that included visits to local Boy and Girl Scout camps, summer schools, hospitals, JCCs, and anywhere else kids our age were spending their summer; I complained that it was too tiring. He spoke with uncomplicated joy of his feelings for Israel; I scoffed and said he lacked the sophistication to grasp the political situation in all of its nuance. Yet Saba never repaid my insolence with anything but love. Smiling, he called me a bad boy; it was the most sincere compliment he could think of. Looking at him looking at me, I could tell that he was gazing not at who I was but who I could one day become if only I opened my heart. I tried to gaze at that future self, too, and the feeling was more intoxicating than any I’d experienced before.

And so, eventually, I started paying less attention to the places we were going and the people we were meeting and the hideous shirts we were forced to wear and more attention to Saba himself. When he came into conflict with someone—like that camp director who wasn’t really keen on letting two wild Israeli kids interrupt his carefully conceived curriculum—he never yelled or lost his temper or puffed out his chest. He spoke with the calm conviction of a kind rabbi who could wait for all eternity while you stumbled around, searching for the truth he’d already discovered ages ago. Yet he was never contrary for the sake of argument alone: His energies were always and only expended in order to serve the community. He fought for that park because he believed the city would benefit from more trees and less asphalt. And he continued to bring Israeli scouts over for visits because he believed the state of Israel would benefit from a few of its own having the chance to make friends with real Americans, which, to that honest and direct son of the South, was the only form of diplomacy that actually mattered.

It took me years to realize not only how profoundly moving Saba’s way of interacting with the world had been, but also how profoundly Jewish. He knew that Jews had no personal savior in whose grace we could bask; if we wanted to be saved, we had to save each other. We are all, as the Talmud teaches us, responsible for one another, and a bond that begins with a few folks putting on the same article of clothing to set themselves apart from the others can thicken, even over the course of one short summer, into something that roots us in a past larger than our own and promises us a future much brighter than any we could’ve imagined.

Saba passed away last month, 90 years old and active to the last. He probably would’ve hated the euphemism “passed away,” preferring instead a more colorful description for life’s inevitable and unceremonious end. But the term is accurate for those of us he left behind: He passed something on to us, to generations of young Israelis who had to travel all the way to Tennessee to get a lesson in embodied Jewish values that cosmopolitan Tel Aviv would rarely, if ever, deign to deliver. Saba showed me how to be strong and proud and kind, and he showed me that you couldn’t truly be any of these things unless you figured out how to be all of them at once. I will never forget that, and I will never forget him, and if someone handed me an ugly T-shirt cheerfully identifying me as a member of my tribe, I’ll do what my Saba did and wear it with a smile.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.