Our Fair City

More than a century ago, Americans could visit a simulated Jerusalem without ever leaving the country

Many of us are either on the go once again or hoping to be footloose and free, able to travel to parts unknown after being cooped up and contained for months on end. Others among us are more inclined to follow in the footsteps of their forebears, who didn’t get out much or preferred to stay close to home, within the borders of the United States.

Even then, back in the early 20th century, the wonders of the wider world were well within reach. All you had to do was to board a train to, say, Chicago in 1893 or St. Louis a decade later to have the kind of eye-popping, jaw-dropping adventure associated with overseas travel, but with considerably less wear-and-tear on the pocketbook and the body. The splendors of a world’s fair awaited.

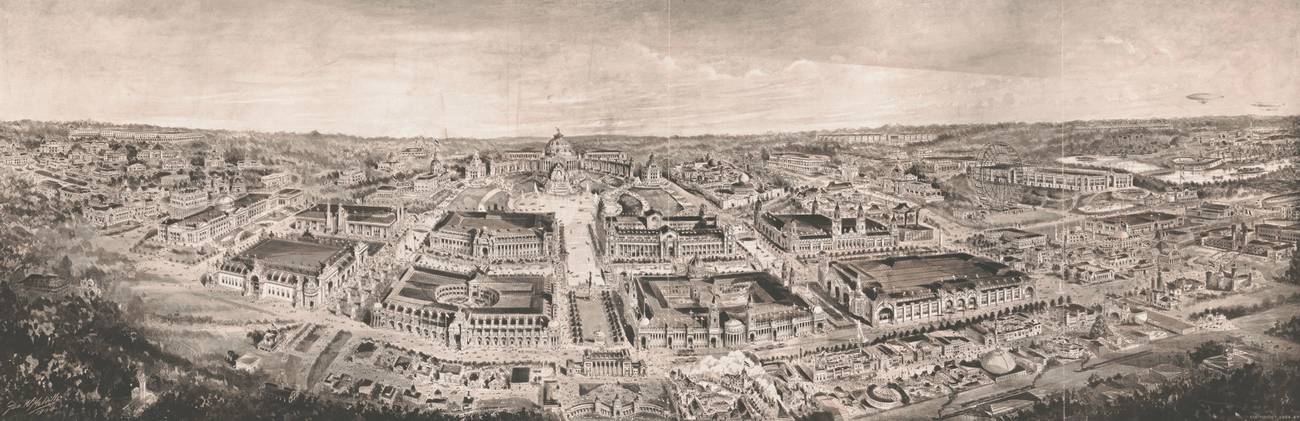

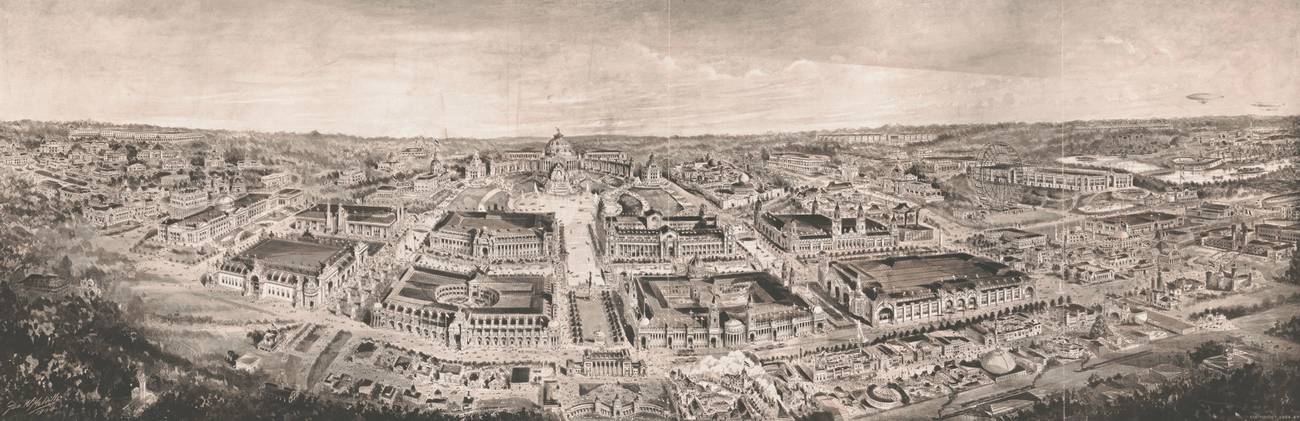

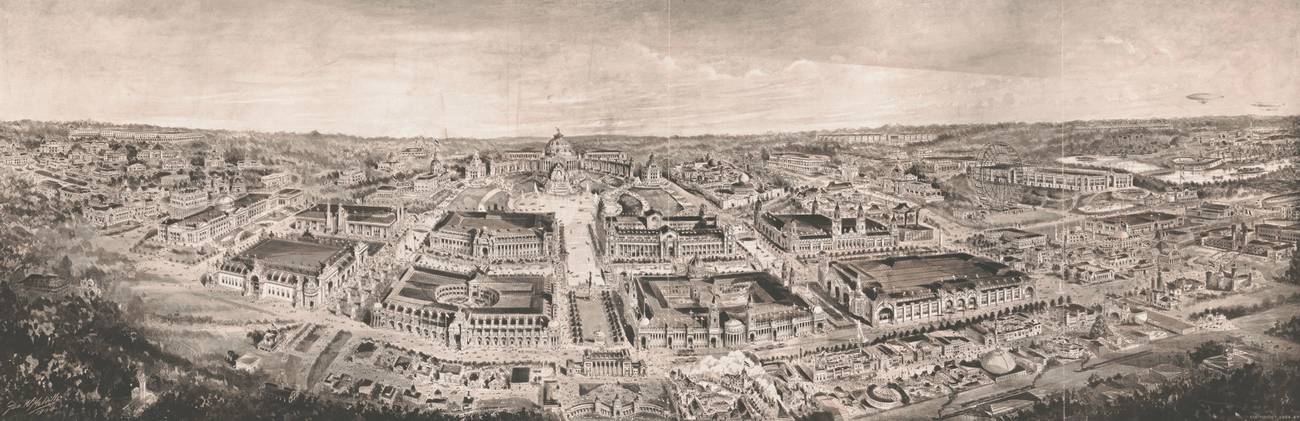

Designed to be spectacular, to take one’s breath away, the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904 made quite a splash. Even grander than its predecessor, the Chicago World’s Fair, which was pretty grand, this undertaking consisted of 1,500 extravagantly scaled buildings situated on over 1,200 acres, every inch of which was covered by fountains, lagoons, canals, grand staircases, esplanades, and sunken gardens and enhanced by “bewildering electrical effects.”

What’s more, Americans no longer had to venture to Europe to encounter an honest-to-goodness palace. St. Louis had plenty: a Palace of Machinery, a Palace of Transportation, a Palace of Manufactures, a Palace of Agriculture, and a Palace of Horticulture where an exhibit representing the state of California featured a huge elephant fashioned out of almonds.

Eager for thrills? The St. Louis World’s Fair boasted an enormous Ferris wheel, where, enthused one fan, “you could see the wheels go round,” along with other popular amusements. Hungry? Fairgoers could choose from among hot dogs, cotton candy, ice cream cones, peanut butter, 40 brands of ketchup, and Jell-O, giving rise, as one culinary historian has put it, to an American “culture of eating.” In need of a lift or a good laugh? The Temple of Mirth was at the ready.

With something for everyone, the St. Louis World’s Fair also carved out plenty of space to attend to the spiritual needs of its visitors by reconstituting the holy city of Jerusalem and plunking down 22 of its streets, bazaars, and venerable sites, as well as several hundred of its “actual inhabitants,” at the very center of the fair grounds. “Do not fail to see the cyclorama of the Crucifixion, the encampment of Bedouins, the Temple of Solomon,” trilled an advertisement for the “Jerusalem Exhibit,” adding rather infelicitously, if helpfully, “commodious clean toilet rooms will be found through-out the grounds, all free.”

Within the 10-acre radius of this “faithful reproduction” of the ancient city, surrounded by its stone walls, fairgoers had the opportunity to walk where Jesus had walked, to worship at one of the city’s many churches and shrines, to ride on a donkey, to purchase Holy Land souvenirs, and to mingle with the city’s natives. As one of its exuberant promoters put it, this version of Jerusalem will “strike visitors as a vision and a dream, and not as a reality,” a curious statement, indeed, given that verisimilitude and authenticity was the project’s calling card, its claim to fame.

Most of the religious sites within its precincts reflected what Christians held dear: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Via Dolorosa, the Garden of Gethsemane. There were two exceptions: Solomon’s Temple and the Western Wall, or what was labeled as the “Jews’ Wailing Place.” Lest you jump to any civic-minded conclusion about its inclusion within the itinerary, take a moment to reflect on how the site was described:

“To the thoughtful, the sight of the Jews who are found there, weeping, chanting between penitential sobs portions of the prophetic writings, is a touching and prophetic one; with tears running down their cheeks, kissing the stones, thrusting their faces into the chinks of the wall and fondly resting their heads against it, they acknowledge their sins and the sins of their nation.”

There’s more like this, but you get the point.

As much a commercial venture as an exercise in pilgrimage—either way, an “irresistible magnet”—the Jerusalem Exhibit capitalized on America’s longstanding relationship to and fascination with the Bible, even as it tapped into the growing wanderlust of some of its more well-heeled citizens and the public’s appetite for simulated experiences. The reconstructed Jerusalem had the added appeal, the “beneficial effect,” of tamping down some of the more louche, unsavory aspects of the fair, elevating its tone.

If some of the good folks of St. Louis had doubts about the integrity of the venture, they kept it to themselves. No one, at least not publicly, thought it the least bit preposterous, let alone hubristic, to deposit an ancient city—and a sacred one, at that—in a bustling American city in the Midwest. The Jerusalem Exhibit was welcomed enthusiastically and warmly applauded by local businessmen, clergy of all stripes, and the president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, who thought it “eminently wise,” and likely not only to “do material good but … add to the attractiveness of the World’s Fair,” a perspective echoed by a local Baptist reverend. “All roads do not lead to Jerusalem,” said he, “but all entrances to the exposition will certainly lead to this New Jerusalem.”

Incorporating Jerusalem into the fair’s wondrous landscape was touted as a way to include faith, religious belief, within the panoply of modern American values the fair was designed to celebrate: progress, know-how, gumption. That this display promised investors substantial returns on their investment didn’t hurt, either. A testament to both American ingenuity and overweening confidence, “Jerusalem, the St. Louis Fair,” as souvenir postcards put it, was even thought to be a mighty improvement on the real thing. Travelers to the Jerusalem of the Middle East received only a “superficial acquaintance” with the city, missing out on its subtleties, pilgrims to the newer Jerusalem were told. “But here, [in St. Louis], there will be a display and a reproduction of many things which thousands of visitors to Jerusalem have never seen.”

Despite the cascade of hosannas, some of the Jewish community’s leaders remained skeptical, especially when a company of “orthodox Hebrews,” largely “patriarchs,” each clad in a “sacred praying robe” (i.e., a tallit), were trotted out along with a Torah scroll as part of the opening day dedication ceremonies and expected to attend publicly to their prayers, before the 10,000-strong audience.

This demonstration didn’t sit well with the American Israelite, for instance, which clucked that the exhibit’s promoters were lacking in “that delicacy of feeling that should mark those in charge of an enterprise of this kind,” and suggested that “if the managers of the Jerusalem reproduction are wise they will change their methods.”

The paper’s caution, though, didn’t stop American Jews at the grassroots from flocking in great numbers to the fair—so much so that the Anglo-Jewish press made a point of announcing in its social columns that Mr. and Mrs. J.C. Harris of Avondale, Ohio, and Miss Hattie August of Rochester, New York, along with of many of their co-religionists, had left town to “take in the sights of the Fair.” Later still, when the High Holidays rolled around, several hundred Jews celebrated Yom Kippur in the ersatz Jerusalem in what can only be called a staging, a confirmation, of the site’s authenticity.

The architects of the American Jerusalem had high hopes that they’d be able to take it on the road and “transport to other places” once the World’s Fair had closed its doors, but that didn’t pan out. The exhibition suffered the same fate as the fair itself which, with the exception of a handful of buildings such as the Palace of Fine Arts (later home to the St. Louis Art Museum), was torn down. The only other enduring legacy of the 1904 World’s Fair was the song “Meet Me in St. Louis,” which Judy Garland popularized years later, and to which, for the sake of history, the verse “Next Year, in St. Louis” might now be added.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.