Pagans in Uniform

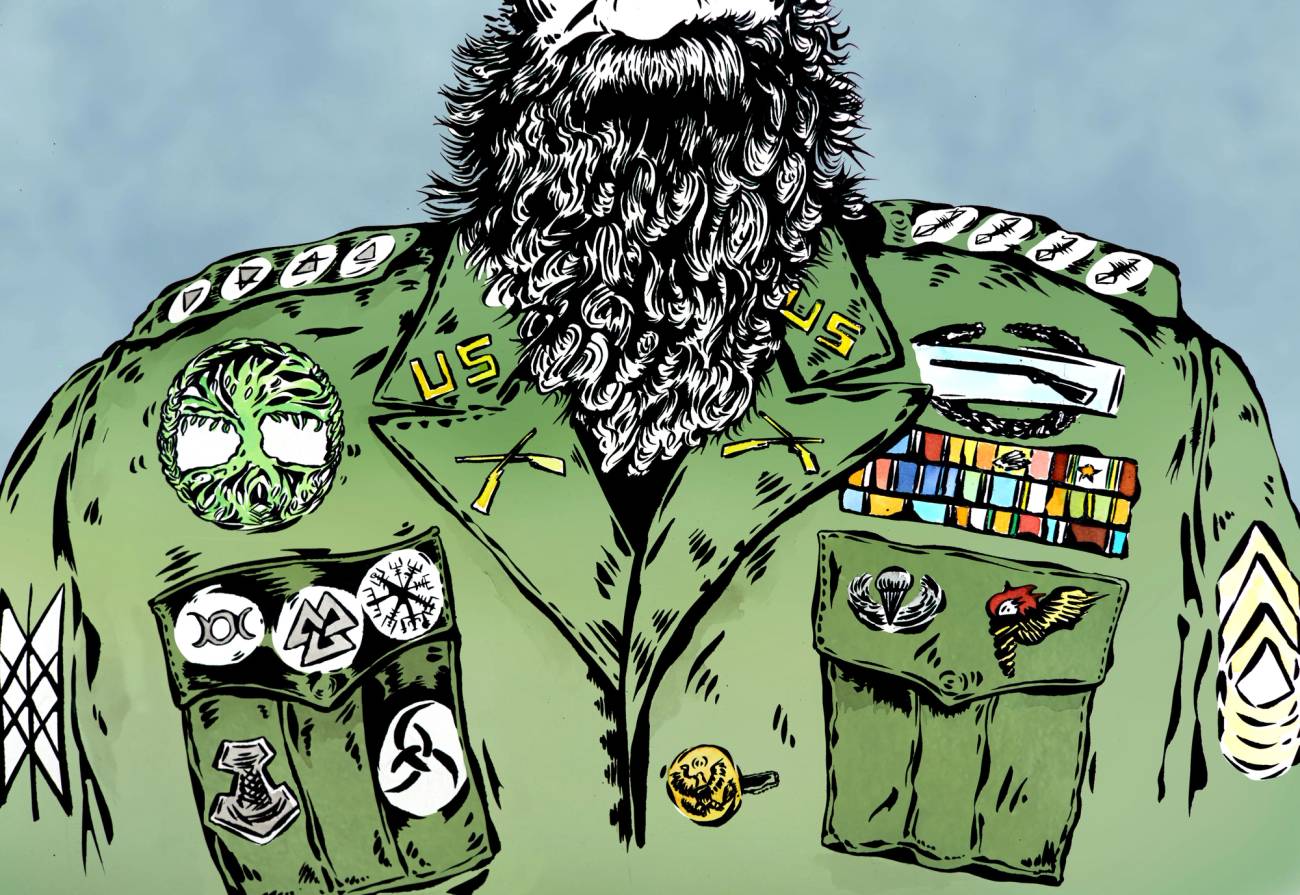

Media reports on followers of old Norse paganism focus on reactionary followers with white supremacist beliefs. But practitioners of the faith in the military are trying to correct the record.

In Linden, North Carolina, a former Methodist church made local news when it became a meeting place for members of the white supremacist Asatru Folk Assembly, who define their movement as an “expression of the native, pre-Christian spirituality of Europe.” Just 30 minutes away at Fort Bragg, pagans in uniform—who adhere to Department of Defense-recognized old Norse pre-Christian beliefs—are eager to let you know that they aren’t affiliated. With the nation on alert for white supremacist threats and extremism in the military, practitioners of Norse paganism within the military are working to correct what they see as mischaracterizations and harmful associations surrounding their faith.

Aside from the Norse thunder god Thor’s portrayal as a benevolent goof in the Marvel cinematic universe, Norse paganism and mythology are most often linked in the American popular imagination with white supremacist ideologies. When the Robert Eggers Viking historical fiction film The Northman was released earlier this year, various media outlets responded to a Guardian piece, which quoted a couple of racist 4Chan posts in support of the film, and speculated about its popularity with white supremacists who co-opt symbols from Norse mythology. In 2019, the film Midsommar depicted Scandinavian pagans as smiling Aryans who love traditional folkways and nature, but not, it would seem, immigrants. (“Stop mass immigration to Halsingland” reads a highway banner near the rural commune where the fair-haired cultists in the film make their home.) Their reverence for Norse runes is perhaps matched only by their enthusiasm for flaying or burning people alive. In the real world, pre-Christian Norse symbols appeared in the 20th century in Third Reich art and heraldry, and in more recent history, on banners and clothing at the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally in 2017, on the Christchurch mosque shooter’s tactical gear in 2019, and most recently, in the Buffalo shooter’s manifesto.

But in an email about Fort Bragg’s Norse pagan community, Major Carlos Ruiz, the deputy chaplain for the 82nd Airborne Division, clarified: “It’s not the same as a ‘whites only’ group that has picked a former Methodist Church in Linden as a gathering place.”

Ruiz said that Norse pagans are what is called a “low-density faith group” in the military, meaning a faith group without many adherents or clergy. There are no Norse pagan chaplains in the Army or any of the other branches of service, according to Ruiz. “When a need for a low-density religious support is brought and requested,” he said, “the Army has a certification process to authorize Distinctive Religious Group Leaders (DRGL). When someone volunteers to lead a group, they just provide some endorsing paperwork from the faith group they are part of.”

From there, he explained, the application goes up to a certain level of command, and includes an initial interview with a chaplain “to assess sincerity and verify credentials.” Then, if and when the volunteer DRGL is approved, they can lead services or studies for that faith group during a deployment or field exercise. “An Army Chaplain also endorses and oversees the DRGL while he/she conducts services,” said Ruiz.

So who are today’s Norse pagans, and what are they doing in the army? Helen A. Berger, a sociologist and resident scholar at Brandeis University’s Women’s Studies Research Center, provided a succinct explanation of Norse pagan practice after the Buffalo shooting this May. First to contend with is the term “pagan” itself. “Today, ‘Heathen’ is an umbrella term used by people who practice various forms of spirituality inspired by Nordic cultures,” Berger wrote, noting that heathenism is a subset of contemporary paganism. “Contemporary Pagans rely on archaeological, historical, and mythological accounts, mixed with modern occult practices, to create a religion that speaks to their lives in the 21st century but is inspired by past practices.”

Sgt. Drake Sholar is the recognized DRGL for the Norse pagan group that meets in Poland, where the 82nd Airborne deployed earlier this year from their home station of Fort Bragg. He said there is some controversy within the community over which term is preferable, pagan or heathen. “In my own opinion,” he wrote in an instant message, “you can go by any name.” While both carry baggage—heathen has negative associations with violent Viking invasions and uncouth behavior, and pagans were frequently maligned in the early Christian Church as the executioners of the first martyrs—Sholar feels confident that today’s practitioners of Old Norse spirituality have no need to shun either name. Society has moved past longship raids and crucifixions, in his estimation, and getting bogged down in past stigmas inhibits the practice of their faith. “Each of us is searching for daily spirituality,” he said. “Humanity as a whole is well aware of its bloody background, no matter who you call your ancestors. What’s important now is showing religious respect and understanding across the board as Norse Pagans, or Heathens, return to a distinguishable religious practice.”

This is a constant battle to overcome and show that Heathenry is and will always be open to those who wish to practice regardless of skin tone, heritage, background, gender, identity, ability, or orientation.

The group in Poland has about 10 people who meet on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, and Sholar said the numbers are “at least triple that” back at Fort Bragg. At the meetings, “we focus one day on the knowledge basis of understanding the Gods, their stories, and other practices surrounding the faith, while the other focuses on spirit work and meditation,” Sholar said. “Not many would imagine a ‘Viking’ crisscrossed, focusing on his chakras, but in reality, Norse Pagans took Teutonic spirit work very seriously, especially when evoking the pantheon of Gods and their energies.”

Other practitioners share Sholar’s commitment to a kinder, gentler heathenism. The religious educational organization The Troth has been working since 1987 to create an inclusive movement of “modern Germanic spiritual practices which opposes racism, bigotry, and white supremacy,” wrote its military liaison, U.S. Navy veteran John Hyatt, via email. The official designation for the Fort Bragg heathen group is the Fort Bragg Asatru Community. “Asatru is probably the oldest term in the contemporary movement of Norse Paganism—people who worship Norse Gods and draw more exclusively from the Norse and Germanic traditions of northern Europe,” said Jefferson Calico, author of Being Viking: Heathenism in Contemporary America, in an email. According to Calico, Asatru is often closely associated with the very progressive Asatru religious denomination in Iceland that began in 1972, but in the United States, can also carry associations with the Asatru Folk Assembly, he said, “and can have a decidedly folkish connotation.”

This concept of “folkish” is key to understanding the white supremacist strain in Norse paganism today. In her post-Buffalo piece, Berger defines “folkish” as referring to the reactionary, white supremacist elements within heathenry who believe Norse spirituality is reserved for those of northern European descent. Hard numbers of folkish practitioners of heathenry are hard to come by, according to Calico, but “it is not a large number of people,” he said. The AFA—Asatru Folk Assembly, which Calico says is the primary representative of folkish heathenry in the U.S.—“has around 700-750 members currently,” he said.

Putting forward a slightly broader definition than Berger, Calico sees many folkish heathens overlapping with other Americans who hold conservative social and political values and opinions. Ideologically, “most folkish Heathens would overlap with many conservative Evangelical Christians,” he said. He estimates between 25% and 30% of heathens hold what he describes as “folkish, right-wing, conservative, and/or libertarian opinions,” with a smaller subset who hold racist, white supremacist, or white nationalist views, “maybe 5-10%,” he wrote. He estimates that leaves 60% who are opposed to the small, ultra-conservative minority and who actively espouse nonracist, anti-racist, or progressive values.

Norse paganism’s relationship with the U.S. military goes back years, including yearslong campaigns to get the Department of Defense to recognize Asatru, heathen, and other pagan faith groups. The Heathen Open Halls Project applied in 2009 to get Asatru and heathenry on the U.S. Army’s religious preference list, according to Hyatt at The Troth. Started by military veteran Josh Heath, Open Halls was intended to serve as an inclusive, not folkish, support resource for heathen service members. In 2017, the Armed Forces Board of Chaplains recognized multiple heathen and pagan religious preferences.

Calico said that heathens in the military make up a small number, maybe 6%, of the overall heathen population in the U.S. (he estimates there are at least a million and a half Americans who identify as pagan, with perhaps 10% identifying specifically as heathen or Asatru). But, he said, “there is research suggesting that Heathens are somewhat statistically overrepresented in the military, in comparison to the average U.S. citizen.” Calico theorizes that the reasons for this are primarily socioeconomic. “Heathens are drawn to serve in the armed forces and police like many other working-class young people who are looking for social mobility and a leg up in the U.S. economy,” he said. “They see the military and police as attainable—and honorable, definitely—jobs that provide both social and economic advancement.” Paganism is a catch-all term in the Pew Research Religious Landscape Study, showing up under the category of “New Age,” which is a primarily white, median-to-low-income demographic, with some or no college.

Sholar says he was drawn to Norse paganism by something different, though. An exploration of his family’s northern Scottish heritage and the Danish and Viking settlements in the region got him interested in the historical Vikings. “Three years later,” he said, “I have found my Path as a Norse Pagan.” For Sholar, that means growing in knowledge, spirituality, and as a part of a community. “Every day is a new opportunity as referenced in our sacred text, The Havamal,” Sholar said:

Only a man who is wide-traveled,

And has wandered far, can know something

About how other men think.

Such a man is wise.

This worldview is apparently at odds with popular associations of white supremacy with Norse paganism, heathenry, or Asatru. And Calico said he isn’t convinced folkish elements have gained much traction among military practitioners. He points not only to the pains heathens at Fort Bragg have taken in the media to distance themselves from the AFA community in Linden, but to a devotional book marketed toward heathens serving in the military, also put out by the AFA. “Because of lack of interest, that pamphlet was rebranded as a devotional for anyone,” said Calico, “And it is now also out of stock.”

Sholar describes himself as “angered and disgusted” by the co-opting of Norse paganism by white supremacists. “Norse Paganism is a well-rounded practice,” he said. “You can be anyone, from any faithbase, and of any color, race, or creed. It is spiritual as well as practical, and encourages you to be better than you were yesterday. It provides that hope that so many seek, and for Soldiers in this chaotic world, Norse Paganism suits them beautifully.”

Hyatt agrees. “Sadly, it’s through [white nationalists] that people often encounter someone who wears a Thor’s hammer or has a rune symbol as a tattoo,” he said. “This is a constant battle to overcome and show that Heathenry is and will always be [emphasis Hyatt’s] open to those who wish to practice regardless of skin tone, heritage, background, gender, identity, ability, or orientation.” In Hyatt’s experience on active duty, “having a religious community and being able to meet with, it is important to preparedness and well-being while serving away from home.”

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.