Plague Weddings

Rokhl’s Golden City: Long before the coronavirus, other epidemics led Jews to create some very strange rituals to ward off disease

While the Israeli government has taken dramatic steps to contain the spread of COVID-19, requiring 14-day quarantine for all travelers entering the country, not every Israeli leader has gotten the public health memo. A miniscandal erupted when Israeli media reported that the rosh yeshiva of Kiseh Rahamim in Bnei Brak, Rabbi Meir Mazuz, had given a speech in which he blamed the spread of the virus on Israel’s Pride Parade, claiming it as divine retribution. Blaming the gays isn’t exactly novel, of course. Extremists in the United States have long been infamous for their efforts to blame everything on the gays.

It’s tempting to read this as a very modern reaction to the erosion of heteronormativity. But the history of European cholera pandemics (the first arriving in the early 19th century) shows us that among Jews, it was long believed that violations of sexual norms were particularly angering to God, and thus precipitated his wrath in the form of disease.

In his forthcoming book, Stepchildren of the Shetl: The Destitute, Disabled, and Mad of Jewish Eastern Europe, 1800-1939, historian Natan Meir notes that in the midst of an 1866 cholera pandemic, rabbis were laying the blame on sins like adultery. We know this because the maskilic Yiddish language newspaper Kol mevaser made a point of criticizing the rabbis for leading their believers astray.

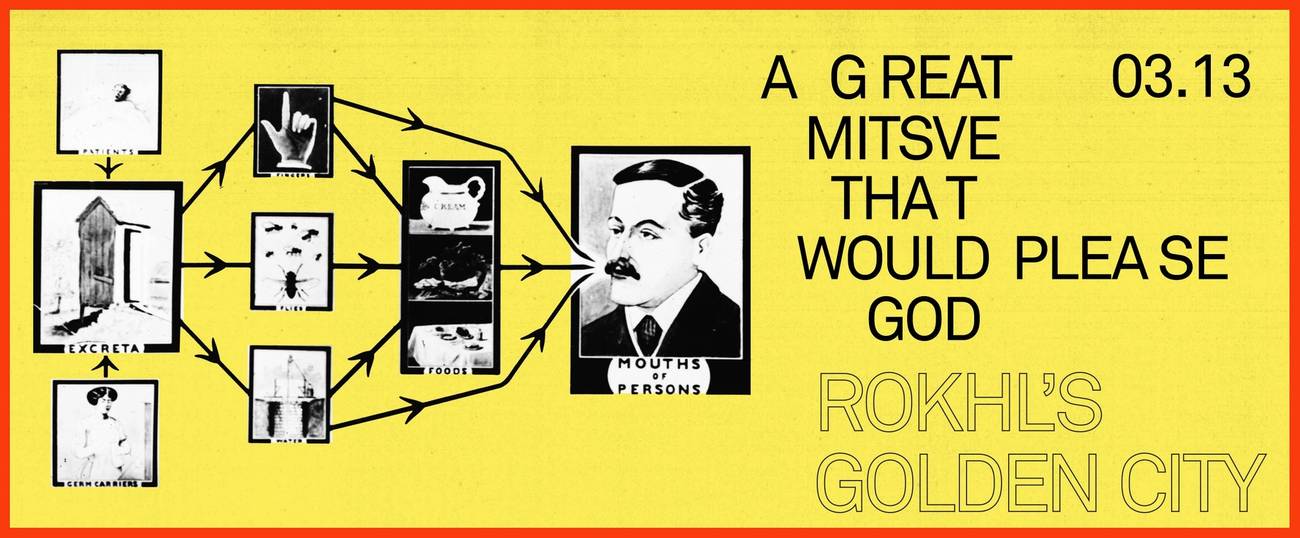

People were understandably terrified of cholera. Forget about a hazy 14-day incubation period. If you were exposed to the cholera bacteria, most likely through infected water, you could develop symptoms in as little as two hours. You can think of cholera as the worst food poisoning imaginable. (The bacteria can also be spread through food, especially seafood.) The major symptom is violent and copious, watery diarrhea. Without rehydration, the patient can quickly become fatally dehydrated. Even worse, in areas with poor sanitation and vulnerable water sources, the high volumes of watery diarrhea produced are a perfect vector for transmission.

Even more terrifying than a potentially fatal disease with absolutely disgusting symptoms, unknown cause, and few adequate treatments is the human inclination to blame other humans, especially the most vulnerable among us. Meir says that one historical source reported that “in the case of an epidemic, it was the custom to call on all members of the community to report any sin that he or she knew about.” A committee of 18 prominent men and a rabbi would then investigate. What could possibly go wrong?

During the 1866 epidemic, the Hasidic community of Uman “declared that Jewish women wearing crinolines and earrings were to blame for the epidemic” and Meir tells us that there is evidence that some women were indeed attacked by self-styled public health avengers, who ripped off their crinolines and beat them. Though it’s not a historical report, in a Hasidic tale from the turn of the 20th century we find another pandemic blamed on adultery. In that story, it’s not until the town’s rabbi and shoykhet (ritual slaughterer) take it upon themselves to murder the adulterers that the disease abates. One hopes that stories like these were meant as instructive fairy tales to frighten rather than accurate transmission of local history.

As far as magical logic goes, ritual murder enacted to placate the forces of death is hardly unheard of among cultures of the world. But murder is likely to attract the attention of the police (see The Wicker Man), as well as pissing off the masses when it doesn’t actually work.

Luckily, the Jews of Eastern Europe had other, more benign, kinds of folk magic to ward off epidemics. The Jewish Dark Continent: Life and Death in the Russian Jewish Settlement is a recent scholarly annotation of S. Ansky’s famous ethnographic expedition of the early 20th century and contains many such folk magics. Author Nathaniel Deutsch notes, for example, that in one place, four girls would be hitched to a plow that they would drag across “a plot of land in the path of the advancing epidemic.” Ordinary people might also wear red string bracelets or rings made of the palms used during the Sukes festival. So far, so innocuous, so good.

However, when it came to the cholera epidemics which stalked the 19th century, the Jews of Eastern Europe developed a unique communal ritual of defense and protection: the cholera wedding. The cholera wedding generally involved finding two of the most marginal residents of the town (whether orphans, beggars, or the physically handicapped) and forcibly marrying them, usually in the cemetery. The cholera wedding, also known as a shvartse khasene (black wedding) or mageyfe khasene (plague wedding) was presented as an ancient Jewish rite, but Meir argues, it was a newly invented, modern response to what was then a newly arrived disease. Because it was a late-developing belief and not textually based, the mechanism by which it was believed to work is open to interpretation.

At this point I should probably put in a content warning, if you hadn’t already stopped reading at violent, watery diarrhea. The plague wedding was intimately related to the treatment of the most marginal people in Jewish society, especially the disabled. And, perhaps it goes without saying, the attitudes toward those people were, in general, dehumanizing and often quite cruel. Traditional Jewish society did value the charitable care of orphans and those who couldn’t take care of themselves. Unfortunately, that care often came with a price, as we will see.

The first evidence of a plague wedding is from 1831, during Russia’s first cholera pandemic and then another written reference to one taking place in 1849 in Krakow. There isn’t much evidence of the weddings, however until the 1860s. At first, the Jewish authorities tried to suppress them, as reported, again, in the maskilic newspaper Kol mevaser. It’s interesting that two of the characteristics Meir notes about the weddings are that they were often raucous parties, and that they were organized by women (hey, ladies be planning weddings, right?). It’s understandable that the rabbis at first sought to discourage these practices and reassert their authority.

By the time of the worst pandemic in 1892, the cholera bacterium was already identified and understood by scientists. The Russian Empire, however, was ill-equipped to fight the disease across its vast area. And in Jewish communities, all previous objections to the cholera wedding had fallen away. The ritual, only a few decades old, was now firmly entrenched, as if passed down from ancient times.

The cholera wedding didn’t have one single interpretation. For example, some rabbis felt it was efficacious because helping to marry off a needy bride was a great mitsve that would please God, all the more so for the marginal of the community who were unlikely to marry in any case. However, what comes across in many of the appalling descriptions of the forcibly married, and their reactions to each other, is that the act was far more callous than charitable. But it was enabled by traditional attitudes around communal charity. Those who had relied on it were seen as being, quite literally, property of the townspeople and thus had no say when their (previously reviled) bodies were needed to protect the town.

But as Meir shows, there was also a strong magical aspect to the cholera wedding, one similar to the ritual of kapores, when a live chicken is taken to receive one’s sins before Yom Kippur. He quotes Yiddish writer Joseph Opatoshu’s story “A Wedding in the Cemetery” for its chilling wedding scene, reminiscent of kapores, but translated onto a human sacrifice. When the time has come to present the unlucky couple with their gifts, in a reversal of the normal social order, a beggar woman goes first. Pulling a tin spoon out of her sack, she “lifted the spoon over her head, spun it over her head once, then twice, as one does with kapores, then laid it on the table crying, ‘It should be away from me and stay with you!’” The rest of the crowd follows suit, chanting, “From me to you,” in what is still begging to be made into a great Yiddish horror movie.

*

In the early years of organized Western medicine, many people, not just Jews, were deeply suspicious of doctors. As Meir describes it, in traditional Jewish communities, the Jewish doctor was associated with apikorsis (heresy) and going to one represented a sinful lack of faith in God’s healing power. It also meant a turning away from traditional folk methods for healing, called zababones in Yiddish. And when the government tried to implement public health measures, Jews were understandably distrustful. After all, this was the same government that had enacted many hateful laws whose goal was to make life worse, not better, for the Jews. These governments were also responsible, directly or indirectly, for much of the violence that Jews would have to endure.

In the early 20th century, a new category of marginal persons appeared: those who carried the physical and mental scars of World War and pogroms. Meir notes that two of the last recorded cholera weddings happened in Odessa in 1922 and involved people who carried the wounds of those events: a woman with an eye gouged out by pogromists, a war veteran who had been wounded and lost the ability to speak.

Thanks to the new, truly global nature of war, the Spanish flu of 1918 was brought back to North America by returning soldiers. And along with the pandemic came the plague wedding. It’s not so surprising to see it popping up in a Jewish capital like New York, but Winnipeg, too? By January 1919, nearly 13,000 people in Winnipeg had contracted the flu and more than 800 had died. Of course people were desperate.

In his new family memoir-in-progress called The End of Her, Tablet executive editor Wayne Hoffman describes the astonishing story of Canada’s first (and possibly last) plague wedding. Held on Nov. 10, 1918, it united Harry Fleckman and Dora Wiseman “at one end of the Shaarey Zedek cemetery in the city’s North End, a ceremony that drew more than a thousand Jewish and gentile guests, with a minyan of 10 Jewish men conducting a funeral for an influenza victim at the other end of the graveyard.” The city’s Yiddish newspapers excoriated the rabbis for allowing such a ceremony to go on, lest it contribute to anyone avoiding real medical care.

Yiddish-speaking Jews in Eastern Europe didn’t just suffer from pogroms and cholera (and flu and typhus and more), they also suffered from poverty, discrimination, and language barriers to medical care. What finally led to the disappearance of the cholera wedding were systematic, well-planned public health initiatives, and self-help organizations like the Society for the Protection of the Health of the Jewish Population (OZE, or Obschestvo zdravookhraneniia evreev in Russian) were emerging. OZE had branches all over Russia, Ukraine, Poland, and Lithuania, some of which continued to provide care to impoverished Jews in the ghettos of WWII. One of the key innovations of OZE was to provide public health information and outreach in Yiddish. OZE campaigns were designed with the unique characteristics of the Jewish community in mind; today we might call them culturally sensitive health care.

Unfortunately, reactionary, anti-medicine beliefs are hardly a thing of the past. The modern anti-vaccination movement is one such example. In the last few years we’ve seen the tragic infiltration of anti-vaccination propaganda into more closed off, traditional Jewish communities, especially ones already poised to reject government interference and where lower English literacy rates leave residents vulnerable to misinformation from outside, pseudoscience hucksters.

The activists of the OZE brilliantly executed their Yiddish language public health initiatives for a vulnerable, distrustful population. It’s an example of what can be done to protect citizens simply by recognizing a community’s unique needs. But even today, when the government does allocate resources to Yiddish-language public health initiatives, too often the products of those initiatives are baffling in their incompetence. During the measles scare of 2019, one Hasidic Twitter user posted a photo from Phelps Hospital in Sleepy Hollow, New York, about 15 minutes from Monsey, a large Yiddish-speaking, Hasidic enclave in Rockland County. The picture showed a Yiddish language sign in the parking lot, warning patients to go to the emergency room entrance if they had a fever or an eruption of measles. The problem was that the text was broken up in such a way that in order to make sense, the sign had to be read from bottom to top.

It would be comical if the consequences weren’t so dire. Such incompetent execution of public health materials further alienates the very people it is meant to be reaching. And with this novel virus upon us, we are about to find out if the government has learned anything from the measles debacle. Lives are on the line and unless we see the loneliest singles among us lining up for plague shidekhs (matches), we can’t count on magic to save us.

NOTE: Because of the uncertainty of the moment, I’m not including any listings for public events this week. I am going to strongly encourage everyone to pre-order Natan Meir’s brilliant Stepchildren of the Shtetl. At the very least it will provide excellent quarantine reading.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.