How the Pledge of Allegiance Helped Me Love ‘Hatikvah’

The nationalist anthem my kids sing at camp makes me uneasy. But I grew up reciting a jingoistic pledge, and I turned out OK.

The Jewish day camp where I sent my two eldest daughters last summer, and where they are returning this summer, did just about everything right. The girls weren’t bullied or beaten. They made friends. Their swimming ability improved drastically. They developed an appreciation for ice pops in long plastic tubes. Every afternoon, they arrived home happily exhausted.

If I had a complaint, it would be with the musical selections. The two of them mastered exactly three new songs last summer. They both know “Yogi Bear,” a harmless nonsense ditty sung to the tune of “Camptown Races.” Our older daughter can now perform a dance routine tightly choreographed to the song “… Baby One More Time,” by Britney Spears.

And then there was “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem.

Before I get to my complicated emotions about national anthems, let me be clear: After singing the song every day for four weeks, my children had no idea what the words to “Hatikvah” are—not in Hebrew, not in English. They can’t even sing it phonetically. The only word they get right is tikvateinu, “our hope” (which, to be fair, is the most important word). Beyond that, they can reproduce just enough syllables, sung to notes that are just close enough to the actual melody, that we feel certain it’s “Hatikvah” they are singing.

And sing it they did. Multiple times a day, for weeks after camp ended, at least once a day one of them launched into their pidgin “Hatikvah.” Every day the words were further from Naphtali Herz Imber’s lyrics, every day the notes were further from Samuel Cohen’s 1888 setting of that old, stirring European folk melody, which became the unofficial Zionist anthem decades before the founding of the state of Israel. But having attended way more days of Jewish camp than nights of professional sports, they learned the melody of “Hatikvah” better than that of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

So if there is Zionist indoctrination going on at the camp, I can’t say it’s very successful. One weekly newsletter described the “Israeli Day” program for the second- and third-graders, a group that included our older daughter. The day “involved pizza making, face painting, Israel Defense Force boot camp, song singing, and learning about Israeli culture.” When I asked Rebekah about the alleged IDF training, she had no idea what I was talking about. Jewish, and Israeli, culture was most reliably present under the auspices of the weekly oneg, or Friday-afternoon Shabbat party. It was to perform at the oneg that Rebekah’s group had learned the Britney number.

*

Marjorie Ingall published a wonderful essay three years ago in Tablet, about why, despite her “shpilkes” about Israel, she sent her daughter to a Zionist camp. “I am no more likely to attend an Israel Day Parade than a Justin Bieber concert,” Ingall wrote. “I hesitate to talk about Israel with my children, and I feel a visceral anxiety upon seeing an Israeli flag.” But when she started researching Jewish sleepaway camps—she very much wanted her daughter to attend a Jewish camp—she “found a terrifying amount of princessery, camps filled with unnervingly sophisticated, spoiled kids with Shabbat dresses more expensive than [her] entire family’s wardrobe.”

The exception? Zionist camps. The Zionist camp that Ingall found for her daughter “makes kids do chores. It does not have spiffy bunks or a lake. The kids dress like shlumps. They are unspoiled and lovely.”

The conundrum that Ingall writes about—great people, simplistic politics—is present at all camps with a political bent (as I learned, in my own youth, at Quaker pacifist camp and at Yiddish socialist camp). And I have seen this paradox so much, in so many places, that it no longer seems like a paradox, least of all at Jewish camp. Some of the best Jews I know—laid-back, warm, tolerant, egalitarian, “unspoiled and lovely,” to use Ingall’s appealing phrase—are in essence kibbutzniks of the 1965 vintage, madly in love with their unchanging, fantasy Israel, ready to get dirt under their fingernails to help build it.

I love these huggable summer-camp Zionists: for their utopian ideals, for their lack of cynicism, and for their ability to teach Israeli folk dancing with fervor and earnestness, even in an age when actual Israelis are either too religious to dance with the opposite sex or so secular that they prefer Skrillex in a Tel Aviv boîte. I love them for their unironic embrace of gaga, the Israeli bastardization of dodge ball that has become an integral part of North American Jewish summer camps. And I envy them their unspoiled optimism about Israel. I wish I could be as optimistic about the United States as they are about a foreign country.

On the other hand, my feelings about patriotism can be summed up by the old, anonymous saying that a flag is just a rag on a pole (or, in some versions, “a schmatte on a stick”). I take my patriotism with heaping spoons of misgiving and hand-wringing, to dilute the simplistic purity encouraged by flags, anthems, and standing at attention. I should add that Jews, in particular, do not have a great history with flags, uniforms, and pledges. To put it mildly.

So would I rather that my daughters not learn “Hatikvah” at summer camp? For the first couple weeks, that was my thinking. But then something changed. One afternoon, I heard Ellie, our younger of the two at camp, reciting another messed up, totally wrong bit of familiar patriotic poesie. It was more disjointed syllables than words, kind of like the teacher in Charlie Brown, but at the end one phrase came through clearly: “ … with puh-liberty and justice for all.”

“Puh-liberty?” I asked.

“Yes,” Ellie said, “puh-liberty. It’s part of the Pledge of Allegiance.”

That’s when that I discovered that the camp staff, loyal American Jews that they are, had been going binational with my children: both “Hatikvah” and the Pledge of Allegiance. And rather than making me more uncomfortable with the indoctrination my children were getting, it made me worry less. It made me chill out.

*

At first, I could not for the life of me figure out why.

Soon it dawned on me. I was raised with the Pledge of Allegiance in school, and I turned out to be me! The canned jingoism, the Cold War–era Constitution-skirting insertion of “under God”—not only did this feature of my childhood fail to turn me into an uncritical, warmongering patriot, but it had, if anything, been a strop on which I had sharpened my reasoning skills.

As an adult, I think national pledges of any kind are idolatrous: We should be pledging allegiance to God, or ethics, or the Good, or doing what’s right, not to fallen, morally compromised nation-states, even the best of them. But one reason I have any analysis of pledges at all is because I was exposed to the big Pledge as a child. And back then, I was kind of thrilled I had the Pledge of Allegiance in school, if only to rebel against.

In sixth grade, when I was last in public school, I had to recite the Pledge every morning. And I decided for a time—a couple weeks maybe? a month?—that I would stand for the Pledge, but when we got to “with liberty and justice for all,” I would say, “with liberty and justice for some.” (I wish I had thought to call it “puh-liberty.”)

Mr. Luce glowered at me when I spoke my emendation of the Pledge aloud. But he did not try to make me recite the Pledge as everyone else did. He never mentioned it. I told my parents what I was doing, and they said that was fine. In fact, the idea had probably come from them, indirectly. Switching back to public school after some Montessori years, I think I had forgotten the Pledge, and had mentioned to them this curious new ritual. They told me why they didn’t like the Pledge, and—if I remember right—they dropped the fact that I had the right not to say it. They told me I should do what I thought best. Then they left it up to me.

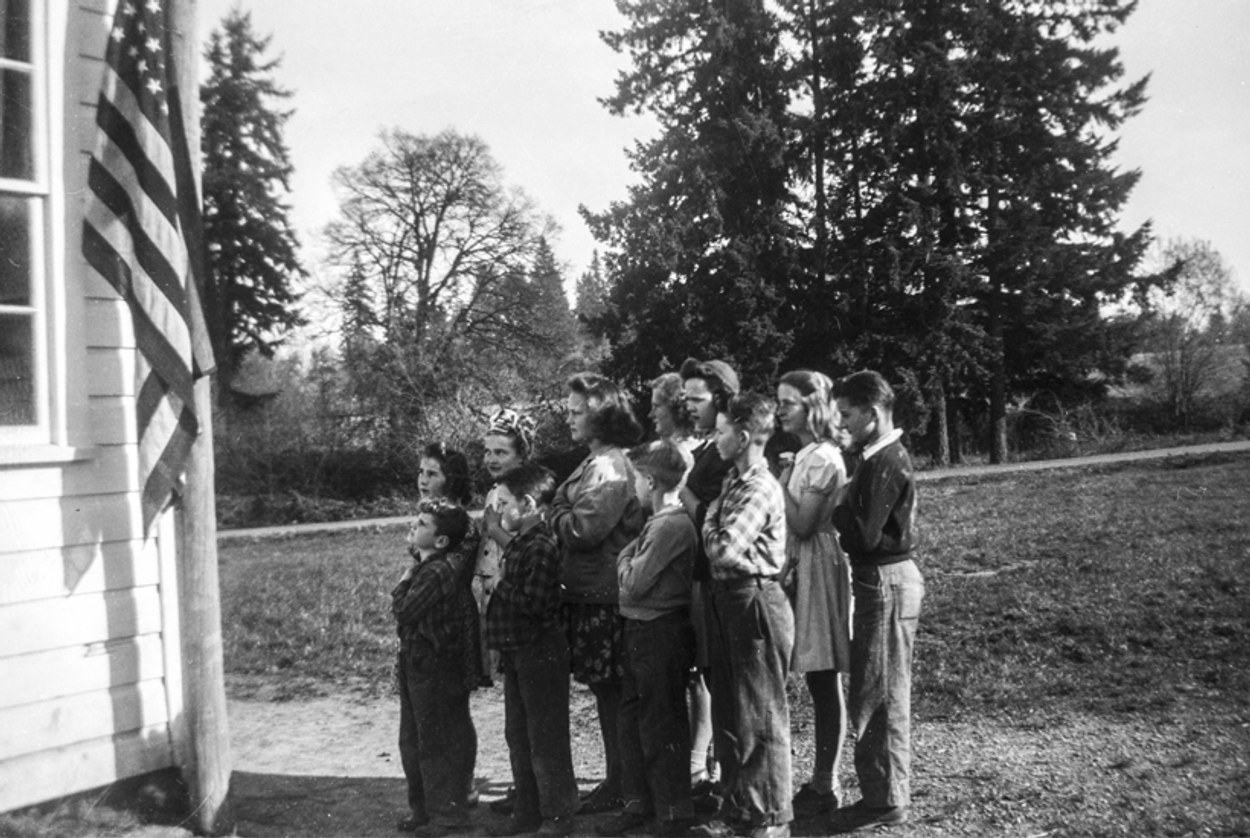

There was another reason, besides the opportunity to test my Constitutional liberties and defy a teacher, that I liked saying the Pledge: It was something I did with my classmates. It was a ritual that all of us—the class was about a third white, a third black, and a third Puerto Rican, and overwhelmingly poor—performed every day. It was a common text, the one poem, if you will, that we all had memorized. It did not function as ideology. I now think that it rarely does.

In fact, I think of the Pledge of Allegiance mainly as part of two of the great pageants of American life: free, public schooling and spectator sports. Two institutions that tend to bring people together, across lines that otherwise divide them. Two institutions that make our country a bit more of a community. “The Star-Spangled Banner” is like that too, and the fact that millions of us are a bit sketchy on the words yet it never seems to matter proves the point that the words should not, indeed cannot, be taken literally. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be stirred to stand and sing that song—or recite that pledge—together.

So “Hatikvah” is OK, I think. Sure, its daily singing at camp is a bit of unthinking, reflexive, casual propagandizing for a country that is, like our own, deeply morally compromised. But context is everything: My daughters are not singing at a rally in Nuremberg, nor at their induction into the Israeli army. They are singing at summer camp, and they don’t even know the words.

At camp, “Hatikvah” is not, or not only, a national anthem. It’s a daily rite. Like games of gaga. Or the Pledge of Allegiance. With puh-liberty and justice for all.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Mark Oppenheimer is Tablet’s editor at large. He hosts the podcast Unorthodox.

Mark Oppenheimer is a Senior Editor at Tablet. He hosts the podcast Unorthodox. He has contributed to Slate and Mother Jones, among many other publications. He is the author, most recently, of Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood. He will be hosting a discussion forum about this article on his newsletter, where you can subscribe for free and submit comments.