Polio’s Jewish History

How a community was affected by the epidemic—and by the scientists who discovered the vaccine

When Philip Roth’s Nemesis first came out 10 years ago, in 2010, I didn’t pay much attention to it. Now, I can’t put it down.

The book tells of a polio epidemic in 1944 that wreaks havoc with the Jews of the Newark, New Jersey, neighborhood known as Weequahic, turning their lives upside down one summer in the midst of WWII. With random cruelty, the virus claims its victims—12-year-olds named Bernie and Myron, Herbie and Arnie—some of whom, only hours before being immured in an iron lung, had been doing what adolescent boys, sprung from school, customarily did during summer vacation: play softball, eat ice cream, and goof around while wolfing down a couple of hot dogs.

As the number of casualties steadily rises, the hapless residents of Weequahic issue a series of admonitions-cum-directives to their children, hoping to keep the virus at bay: No swimming in the neighborhood pool, drinking from public water fountains, or using a pay phone, much less a public toilet. Swatting flies and the continual washing of hands are strongly encouraged, along with taking it easy when playing ball or skipping rope. “‘Overexertion’ was suspected of being yet another possible cause of polio,” Roth writes of his characters who anxiously search for something, anything, to explain the virus’s intrusion into their lives.

While some of Newark’s Jewish residents assail exercise, others have it in for the hot dogs from Syd’s, a local hangout. Though its proprietor, his livelihood in jeopardy, rails against the idea—“A boiled hot dog—how do you get polio from a boiled hot dog?”—the women of Weequahic hold tight to their beliefs. When Alan, a personable neighborhood kid, who, when not a regular at Syd’s, keeps his bedroom as well as his person nice and neat, inexplicably succumbs to the virus, his distraught aunt wants to know “why couldn’t he wait to get home and take something from the Frigidaire?”

Food from the Frigidaire, swatting flies, and washing hands are no match for polio, which, in Roth’s account, doggedly follows the more fortunate of Newark’s Jewish youngsters to Indian Hill, a summer camp in the Poconos. Even amid its idyllic surroundings where, once a week, American Jewish boys and girls, sporting feathers and fringe, whoop it up around the campfire, communing with nature and with one another, no one is immune. Before long, Indian Hill comes to an abrupt close as some campers fall ill and others are collected by their parents and removed forthwith from the camp grounds, lest they share a similar fate.

Eventually, as summer turns to fall, things simmer down and seemingly return to normal in Newark and elsewhere. But the polio virus leaves its mark, psychically as well as physically, prompting some of its victims to butt heads with God. “Why does he place one Weequahic child in polio-ridden Newark for the summer and another in the splendid sanctuary of the Poconos?” asks the book’s central character, Bucky Cantor, whose own life is irrevocably impaired by the polio epidemic of 1944. No one, least of all the divine, comes out ahead.

*

Nemesis, as they say in the movies, was “inspired by real life events.” The wartime epidemic it depicts and those that followed well into the 1950s hit America hard, propelling its anxious citizens to scramble for answers about what caused the disease—the milk supply? bugs? immigrants?—and hard-pressed scientists to come up with a cure. Its pace accelerating rather than diminishing over time, polio “mocked the endeavors of Medicine’s greatest geniuses,” somberly observed the American Israelite.

The disease also put the parenting skills of American Jewry’s moms and dads to the test, leading many of them to send their children, even the youngest, most ill-equipped among them, to sleep-away camp for the summer. “Breathe the fresh air,” the acclaimed novelist Chaim Potok recalled his father telling him. “Have a good time. He did not say what I read on his face and in his eyes: I am sending you out of the city so you will be far away from this sickness that is crippling children.” Potok turned out to be a happy camper; Daniel Krasner, who lived in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Flatbush, was not. Only 6 years old when he was “shipped off” to Camp Massad in 1946, he sent a series of importuning postcards to his mother, one every 2-3 days, and each a variant of “I hate camp. Take me home.” Determined to keep her young son out of harm’s way, she ignored his entreaties. Then again, Mrs. Krasner saved the letters, suggesting they tugged at her heart.

American Jewish newspapers closely followed the trajectory of the disease. Some, like the Jewish Advocate, issued precautions, advising its readers in 1949 to “observe the golden rule of cleanliness.” Others, like the Forward, posted the latest tally of polio victims on its front pages and brought its readers up to speed on efforts to develop a polio vaccine. Still others encouraged the community’s participation in fundraising drives. “Let’s all fight polio. Plan a Kids Karnival for your block,” cheered the American Israelite in 1954, referring to what was then a popular Midwestern exercise in grassroots activism.

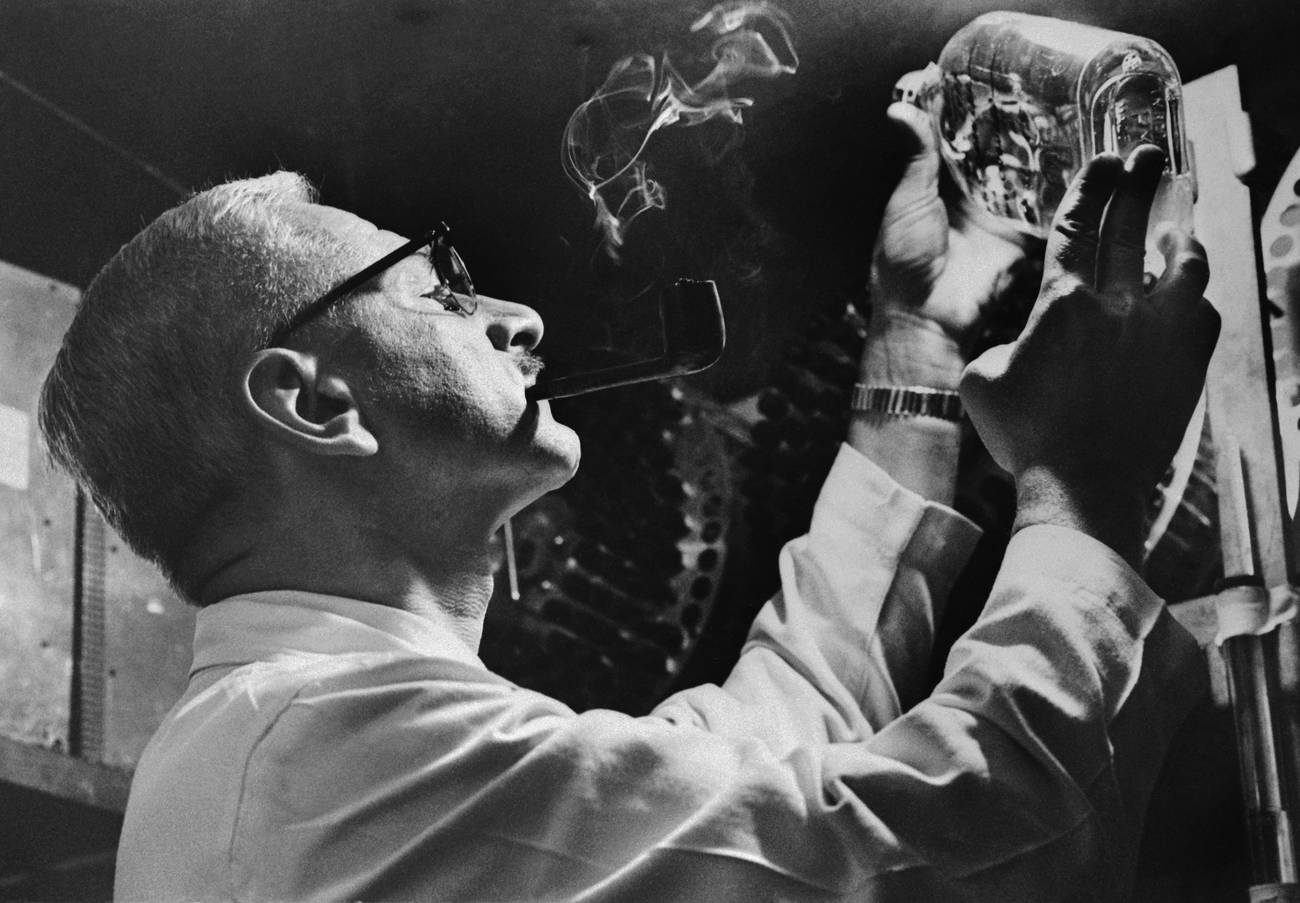

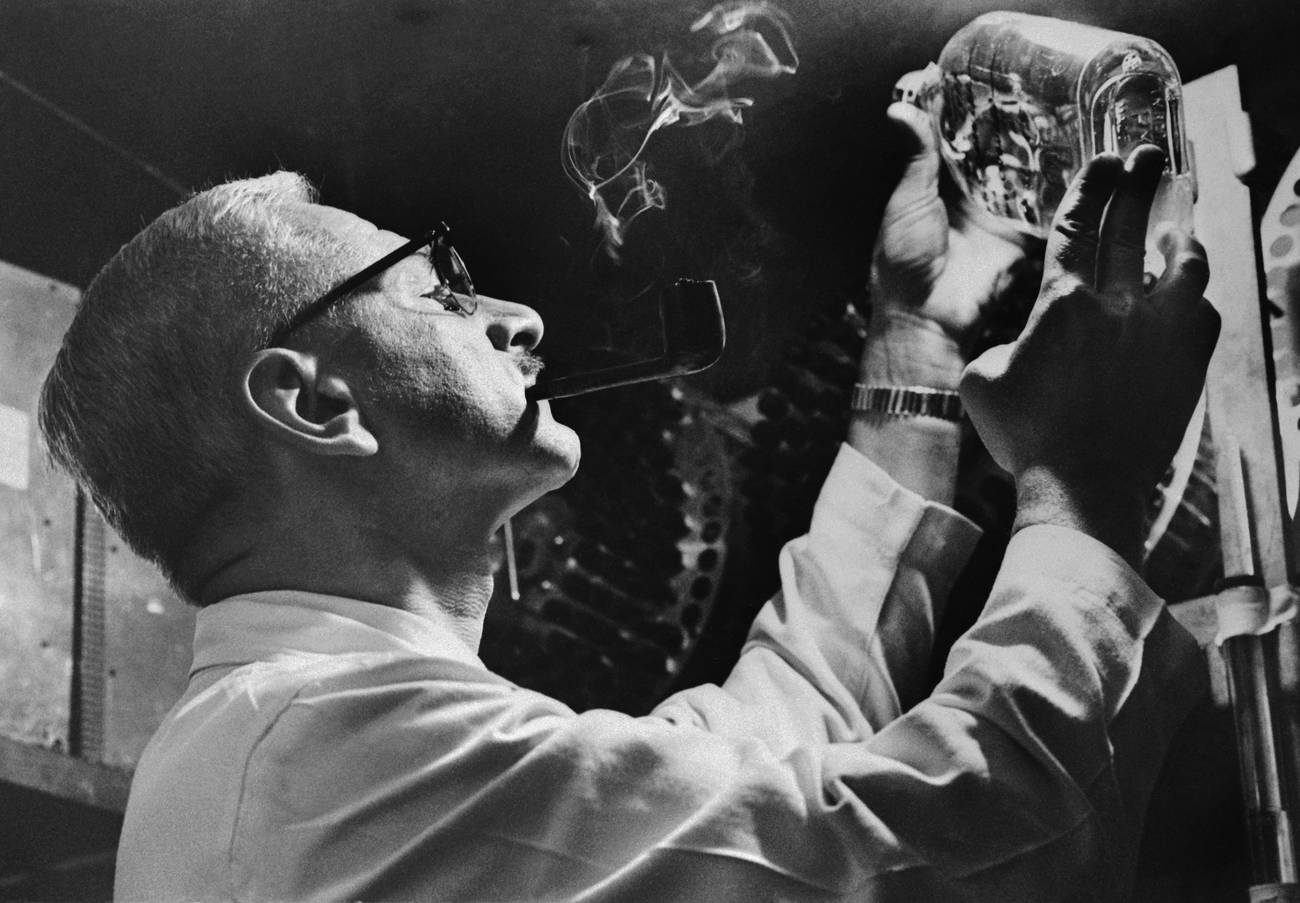

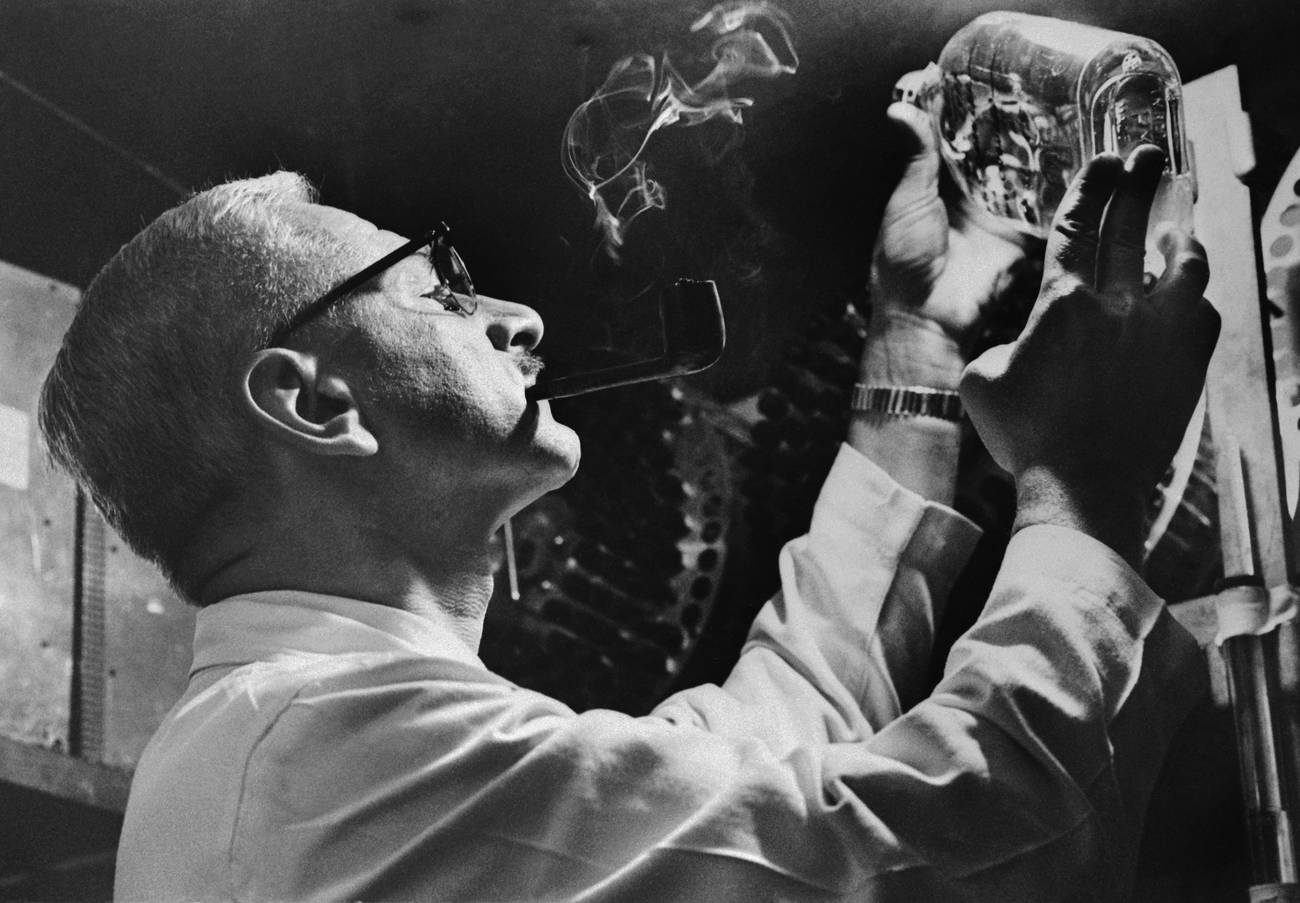

A year after that, in 1955, the American public was informed, at long last, that the “vaccine works. It is safe, effective and potent.” When the news broke, church bells pealed and car horns honked in celebration. The subsequent revelation that there were two viable vaccines, the result of research conducted by Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, American Jewish scientists working independently of, and often competitively with, each other, boosted the Jewish community’s spirits even further: Its boys saved the day.

American Jews made much of the scientists’ Jewish background—Salk grew up in a series of Jewish neighborhoods in the Bronx and Queens, while Sabin emigrated from Poland in 1921—feting them at gala dinners and showering them as well as their parents with honors. For having raised their brainy son in a “home of love, a simple Jewish home,” Salk’s mother and father received the Best Jewish Parents of the Year Award from the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies in 1955.

Even the most ardent of anti-Semites took note and held their tongues—and their fire. An editorial in the Michigan Catholic put it this way: “It almost seems providential that the honor of defeating the fearful scourge of polio should have fallen to a member of a group so often, and so unfairly, the butt of hate-laden calumny.” When this choice bit made the rounds, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency responded with a headline that just about said it all: “Catholics Hail Dr. Salk as Rebuff to American Anti-Semites.”

Well, there’s that. Then, as now, we look for, and take comfort from, the merest sliver of a silver lining. American Jews of the postwar era found theirs in the medical breakthroughs made by two of their own; we in America of the 21st century still await ours. In the meantime, Philip Roth keeps us company, while also inspiring the hope that someone within our own literary ranks might be attending to the scourge of 2020 with as much tenderness and delicacy as he attended to the medical menace that imperiled his generation. To which we, along with the grieving characters in Roth’s fictional universe,say “Omein.”

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.