Precious Medals

Even though he always insisted, ‘I didn’t do anything,’ my father finally got the military medals he earned in WWII—and I finally heard his stories about his service

To hear my 92-year-old father tell it, WWII was one great big, if somewhat scary, adventure on the island of Guam. Sure, there were land mines, and Japanese snipers hiding in the jungle, but there was also basketball and weekly beer and movies featuring Betty Grable and Ida Lupino. “I didn’t do anything,” Dad often said of his service. But he did. He showed up to serve his country, along with 16 million other Americans.

And now, more than 70 years after his tenure in the Pacific Theater, he finally has the medals to show for it: the U.S. Navy medal, the Asia Pacific Theater Medal, and the Victory Medal.

“I did it because of you,” Dad said, after telling me that he had contacted his Delaware congresswoman, Lisa Blunt Rochester, when he saw her campaign brochure with the promise to help veterans with health issues and retrieval of military service awards.

I knew he wasn’t teasing me, as he had done throughout my life, but I also knew that this was only a half-truth. My father did want those medals, even though, for more than a decade, he and my mother have been more interested in divesting themselves of objects. During the past decade, he has increasingly identified as a WWII veteran, even as his Greatest Generation peers are continuing to die off, about 1,000 daily. He wears a black cap embossed with gold WWII lettering to the doctor’s office and to the supermarket.

But he also knew that I was interested in his medals because I had interviewed him about his service, had written about him, and submitted his story to the Veterans History Project (VHP) of the Library of Congress. And because for the past 16 years, our father-daughter bond has tightened and deepened not only on the strength of our conversations about his WWII service, but also through sharing stories of my VHP interviews with more than a dozen other “GI Jews,” as historian Deborah Dash Moore had dubbed them in her seminal 2004 book.

I had also bought Dad the DVD of the GI Jews documentary, released last May, which featured interviews with Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, and Henry Kissinger, among others. I had been moved when first seeing the film on PBS and then again with my older son, Jeremy, at the Washington, D.C., JCC Jewish Film Festival. But it wasn’t until I sat with Dad in my parents’ family room, listening to him say “yes,” “right,” and “no,” in response to Brooks and others talking about cheeseburgers, anti-Semitism, and the Holocaust—in that order—that my tears came.

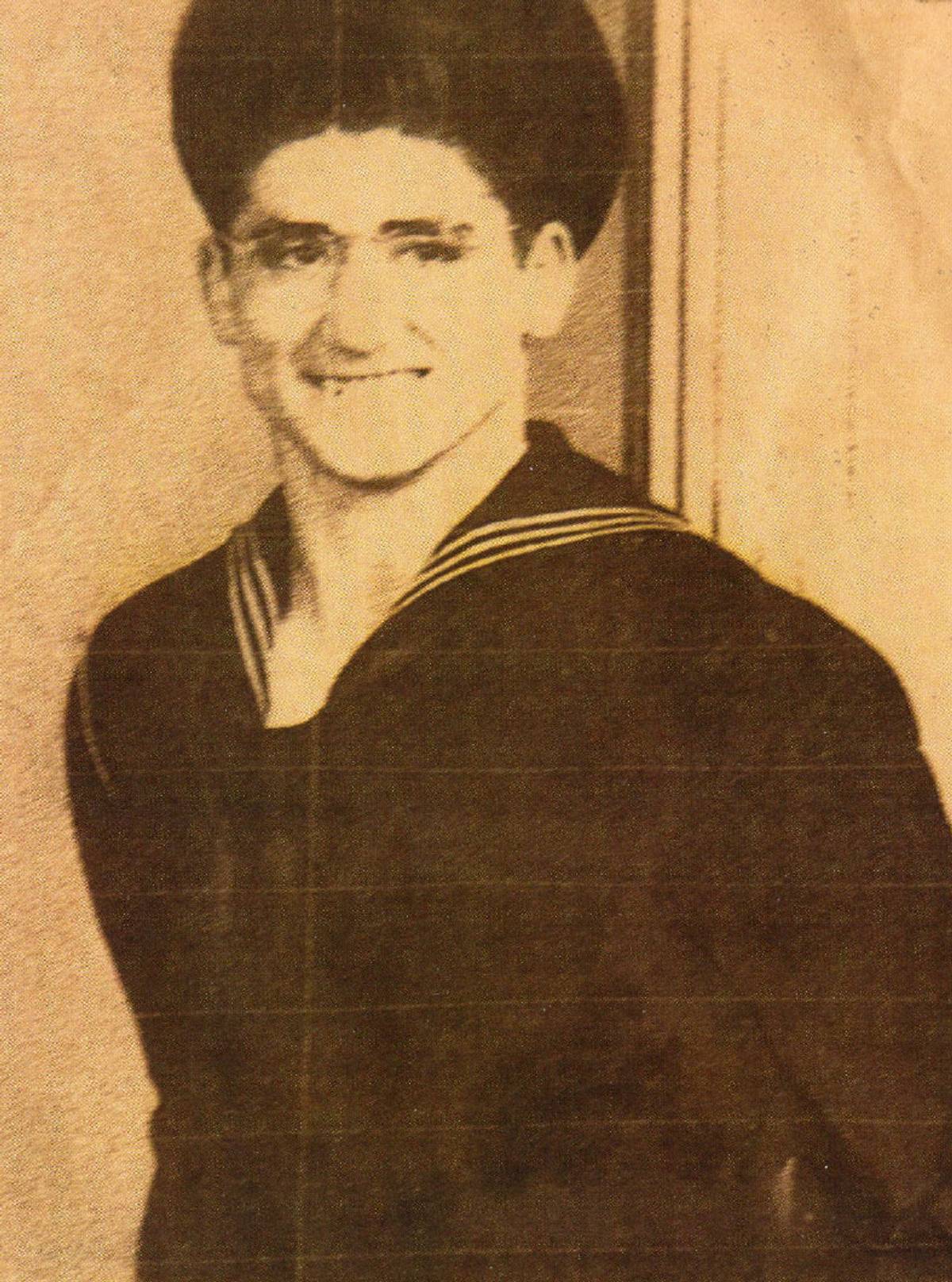

I don’t think that my father noticed my tears or sprouted tears of his own. But after that showing, he “lent” my husband Charlie and me a video of sorts (more like a PowerPoint presentation) on the military service of Delaware Jews, which he had received from the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware. The raw audio and grainy black and white photos in this video were no match for the handsome production quality of GI Jews, but this amateur archival footage about ordinary small-town men and women was riveting and throat-catching in a different way than listening to the tales of Brooks and Reiner. This one featured a narrator who sounded like one of my former Hebrew school teachers; my dentist, a former prisoner of war; my father’s beloved cousin Harry, who had served in both the Pacific and European theaters, and Dad himself, at age 19, sporting “casual” Navy attire.

Like Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner, my father is a storyteller, performer, and deliverer of a combination of self-deprecating and “take my commanding officer—please!” humor. He has been generous in relating the more amusing details of his service: how he had attempted to become a signalman, how he had served as “head guard” for the makeshift hut-like lavatory, and how he had called himself “the famous singer” while cutting a version of “Besame Mucho” at a USO in Chicago to send to his mother. But he mostly kept his memorabilia or any mention of it to himself.

It was only after I noodged him about such items as V-mail, discharge papers, and a photo of himself with his best buddy on Guam, a religious Christian from Indiana, that he let me examine part of his military cache.

Mostly, in our WWII conversations, Dad didn’t talk about what he had kept with him from the war, but he did express regret that he hadn’t saved certain items, like his H (for Hebrew) dog tags. Maybe this was why I often found myself buying him WWII-related tchotchkes, (magnets, bookmarks, buttons) whenever Charlie and I came upon them at visitor’s centers or museums in Washington, D.C., Hyde Park, New York, or Normandy, France. Or maybe because as the years went by, he seldom let one of my visits pass without offering up more and more references to his wartime, identity-forming experience as a late adolescent. As I told my son Benjy, who had transcribed the audio of our father-daughter interview, “WWII was Zayde’s college experience.”

Several weeks after receiving his medals, Dad met Lisa Blunt Rochester at a political forum in Wilmington. He thanked her for what she had done, and she asked him if she could interview him about what he had done. This time, he didn’t say, “I didn’t do anything.”

And even though, like many WWII vets, Dad doesn’t wear his feelings on his sleeve, he couldn’t keep the astonishment and excitement out of his voice when he told me about how the congresswoman had shown up at his home, accompanied by a cadre of staff members and photographers, offering praise and admiration for his wartime service. And he was still basking in photo-op afterglow when I visited him and my mother several weeks later.

At the end of this visit, before we said goodbye, Dad surprised me by giving me the small tan prayer book, published in 1943, that he had received from the National Jewish Welfare Board, called Jews in the Armed Forces of the United States. Skimming the preface, I was struck by the prayer book’s mission statement: “[T]his little volume of devotion serves not only the men who use it, but also the highest ideal of America.”

Dad’s prayer book is intact, if worn and wrinkled. And it was obvious he had used it. In fact, he had written “Daily, p. 127,” inside the title page to refer to the first of the morning devotional prayers.

As for his medals, they are now arrayed with their candy-striped ribbons on a soft yellow cloth in a black frame. “You and [your brother] Dave can have them,” Dad said. “Later.”

Marla Brown Fogelman is a freelance writer in New York City. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Parents, The Forward, Moment, and other national and regional publications.