A Pentecostalist minister who had pastored churches in Illinois, Florida, and California, the Rev. Troy Perry was defrocked in the early 1960s for his homosexuality. This did not mark the end of his time in the pulpit, however; in fact, it marked a whole new beginning. In 1968, Perry founded Metropolitan Community Church, a Christian denomination intended to affirm members of the LGBTQ community.

MCC started with prayers and hymns during a gathering of a dozen people in Perry’s Southern California living room in October 1968—nearly a year before Stonewall. (A neighbor was anxious about getting raided by law enforcement.) Today, with churches in over 20 countries, on every inhabited continent, MCC boasts that it has been “at the vanguard of civil and human rights movements by addressing issues of race, gender, sexual orientation, economics, climate change, aging, and global human rights for over 50 years.” Both Perry and MCC have been present for and presided over the various 20th- and early-21st-century LGBTQ fights for equality. Although like many Christian churches today, it faces membership challenges, MCC still sees itself as a part of an ongoing struggle, even if the struggle has metastasized and shifted from the ones it originally faced in LA a half-century ago.

Perry turns 81 years old this July, and while he stepped down from his leadership of MCC 15 years ago, he is still a dynamic presence in his role as moderator emeritus.

Born in Tallahasee, Florida, Perry has the affable Southern twang commonly associated with the kind of pastor who can casually proof-text lengthy scripture passages in conversation. (He also has a parrot, who was an unmistakable presence during my phone chat with Perry, with a friendly effervescence she shares with her owner.) He’s gracious; even when I got mixed up by our respective time zones and called him at the wrong time, Perry made me feel as though he had all the time in the world for me and my questions, patiently answering them in lively detail.

But beneath his disarming, easygoing demeanor is a fighter.

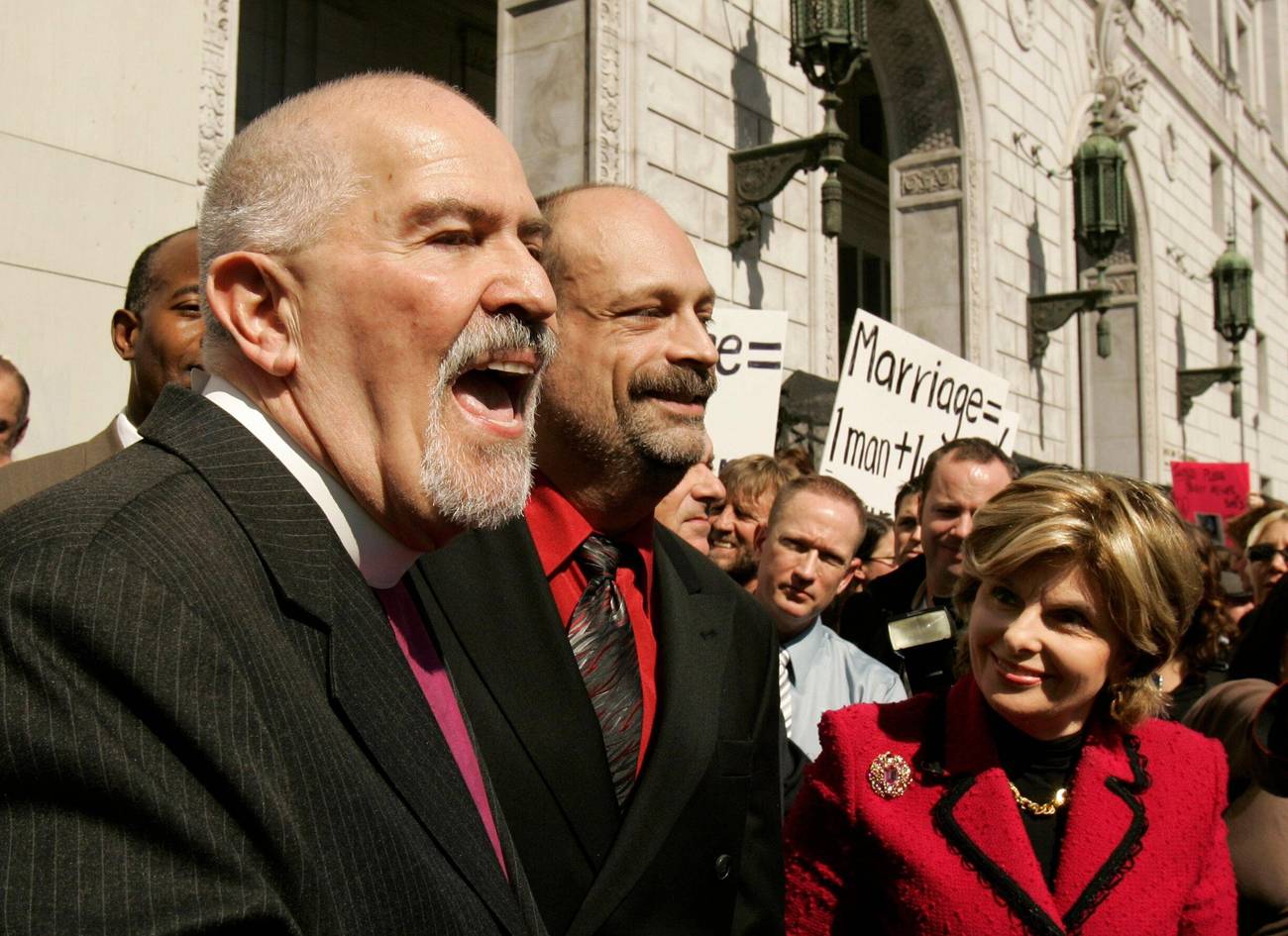

Same-sex marriage was one of his fights from the beginning, long before it was a major political issue: In December 1968, just two months after MCC’s first meeting in his living room, Perry performed what Time magazine declared the first public same-sex wedding in the U.S.

“I always believed in marriage. I was one of those strange gay men who talked about marriage,” Perry told me through laughter. “And marriage was just very, very important to me, and so all my life, I fought for that.”

Marriage was just one theater of operations for Perry and MCC.

“I used to say, years ago,” Perry said, “the one thing I had to fight for, if I was not going to fight for anything else—of course, I fought for everything—was the rights of my members to have a job. People have to work, and that includes my community, too.” That fight took different forms: picketing in 1969 in front of States Steamship Co. offices when it fired a man for coming out, and in 1977, when Perry told reporters from the steps of downtown LA’s Federal Building that he intended to fast there publicly “until death if necessary,” in order to raise $100,000 to fight the Briggs Initiative, a proposed amendment to the state’s education code that would ban gay and lesbian California teachers from working in the state’s public schools.

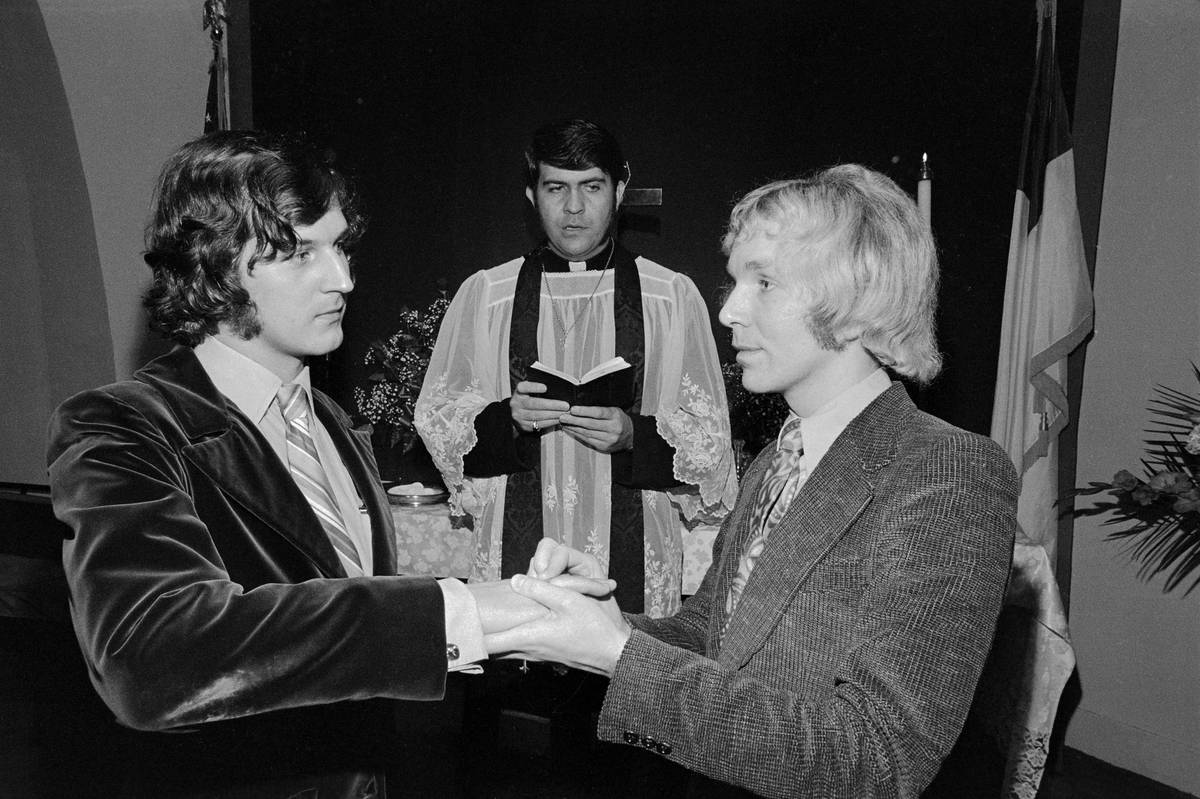

Perry officiates a religious wedding ceremony between Michel Girouard and Rejean Tremblay at the Metropolitan Community Church, Los Angeles, 1972Bettmann/Getty

The church has also endured its share of troubles. MCC has faced anti-LGBTQ violence, particularly during what Perry terms a period of persecution in the 1970s when they lost five churches to arson—including a New Orleans gay bar called the Upstairs Lounge where MCC members were holding a meeting; it was the worst mass murder of LGBTQ persons in the U.S. until the Pulse night club massacre in 2016. According to the MCC History Project, their churches began to experience the full brunt of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the mid-1980s; the Rev. Elder Don Eastman wrote that by the time effective HIV treatments became available in 1996, MCC had lost one-third of its congregants. “I don’t believe that any disease, I don’t care what it is, is a gift from God to a class of people,” Perry said to the Rev. Jerry Falwell in 1983 during a televised debate. “We don’t want political games played with this issue. We want to make sure that people don’t die.”

A commitment to justice seems to sustain MCC through difficulties and obstacles over the years, going beyond simply making members feel a certain way. “Someone said to me one day, ‘Reverend Perry, the difference between a welcome and affirming congregation—where they say you’re welcome and we’re going to affirm you as gay people in our church—and MCC, is they celebrate gay pride once a year. You celebrate it every Sunday.”

Perry founded MCC as a Protestant denomination, a general term that can (but does not always) include Christians who differ to varying degrees with Roman Catholicism in their belief that salvation is attained through faith alone, the view that the Bible is the sole authoritative text to know God’s will—making official church teaching and tradition superfluous—and the symbolic meaning of bread and wine at communion. As a recognition that MCC would be including people from various denominations, Perry wore borrowed robes from a Congregationalist minister friend who insisted that it would be most effective if Perry “preached like a Pentecostal” but dressed “like a Catholic.”

Today, MCC’s denominational mission statement says it “proclaims and practices a spirituality that is anchored in the liberating Gospel of Jesus Christ and confronts the issues of our volatile, uncertain, and complex world,” with a focus on developing inclusive, compassionate leaders, ministries, and congregations that “integrate sexuality and spirituality,” while working for justice and growing spiritually.

There’s a centralized hierarchy, with a general conference made up of both clergy and laity that meets every three years to choose a moderator (leader) and governing board. The moderator functions as the voice of the church’s vision and mission, and is responsible for guiding the church to accomplish those things, for example, by choosing elders, the church’s spiritual leaders, for approval by the governing board.

As much a movement as a faith denomination, MCC is not doctrinal, meaning there’s no central creed all members must profess. Because it’s a denomination, however, that means “there is a thread,” as Perry describes it, that runs through every location that makes it clear you are at an MCC church. In addition to a pastiche of practices from other denominations, each MCC church is undergirded by four core values of inclusion, justice, community, and spiritual transformation.

Every MCC church also shares a commitment to open communion at its services.

Perry explained: “There is not an MCC in the world that doesn’t open communion every Sunday in the service by saying, ‘In Metropolitan Community Church, we want you to know that this is an open communion. You don’t have to be a member of this church, or any church, this is the Lord’s table, not ours.’” The symbolism of this act, in which bread is eaten and wine is consumed in keeping with Christ’s command to his followers at his Last Supper before his death to “do this in memory of me,” can mean different things to different people. At MCC, members may bring to it the beliefs of the faith in which they were raised, while other members may simply find it a personally meaningful ritual that has nothing to do with Christ at all.

“You can believe whatever you like,” said the Rev. Kharma Amos, resource development team lead for MCC, whose portfolio includes communications. The emphasis is on community; as Perry notes, Jesus, after all, even welcomed his betrayer Judas at the Last Supper.

Due to the inclusive, movement-oriented nature of the church, official membership numbers are hard to come by. “There are plenty of people,” Amos said, “who are full participants who never quote-unquote ‘join.’” Amos said she would “hesitate to guess” the average age of individuals joining today, without official statistics (“we don’t even count membership anymore,” she said, preferring instead to track regular attendance at services), but noted that MCC membership tends to be older and whiter on the whole, but there is still “a great deal of diversity.”

Perry stands in his burned-down church, Los Angeles, 1973Anthony Friedkin

Indeed, both Perry and Amos said MCC is growing in Latin America, with a population that Amos said “that skews younger and more trans.”

“We go where people ask us to come to support them,” Amos said. “That may or may not be a church or may not be a worshipping community—or it might be. But its primary objective is something humanitarian, or the movement part. MCC was really instrumental in Eastern Europe at one time when they were beginning their first Pride celebration, for example.”

Unlike a secular nonprofit or NGO, MCC can be present as a religious authority to help counter anti-LGBTQ narratives from powerful religious leaders or state-run churches, “It’s absolutely combined with the movement part,” said Amos, saying that when asked, MCC steps in, “to be a religious voice in the public sphere.”

The story of expansion changes, however, when the discussion moves back home to the United States.

“Like most Christian churches,” Perry said, “there is a flattening of growth. We’re still getting young people, but not like we once did.” He says a poll at the five-year anniversary of MCC’s founding revealed the average age of members to be around 28 years old. Today, he said, it’s “much higher than that.” Describing the clerical ordination of over three dozen individuals at MCC’s 2019 general conference in Orlando, Perry estimated the average age was around 45 years old.

In his first sermon to MCC on that night in October 1968, Perry drew allusions from the Book of Job, the story of David and Goliath, and the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Philippians. It’s hard to imagine that such a scripturally dense sermon would resonate much with newcomers today, when religious participation in the U.S. is in decline and nearly a quarter of Americans profess no religious belief at all.

While younger LGBTQ Americans today still experience discrimination or oppression for their sexuality, the numbers mean its source is less likely to be organized religion than in previous decades. Accordingly, it would make sense that they might not be especially interested in finding an affirming denomination (at any rate, membership in other progressive mainline Protestant denominations is also declining).

Perry says newcomers now are a combination of people leaving other denominations and unchurched “nones,” who professed no religion previously, but still tilting toward the former group. Struggles over LGBTQ issues remain at the local levels of some denominations, which Perry says still attracts members over to MCC.

There might be other reasons, as well, Amos said: “Certainly in the United States and perhaps more so in some other countries, the loudest, most anti-gay voices are Christian or otherwise religious voices. Why the heck would you go looking for that if you didn’t grow up in it?”

In some sense, however, Perry says slowed growth is a measure of success: “I’ve fought very hard to get other churches to change, and they have,” he said. “I used to say we were working to work ourselves out of business.”

Perry quickly noted that his remark was tongue in cheek, observing that while many mainline Protestant denominations now accept LGBTQ members, “I still can’t go home to my Pentecostal church.”

MCC’s history takes the form of an arc, said Amos: “We were the quote ‘gay church,’ in the, you know, early 1970s, and then we became the AIDS church, we were the church that was responding to the AIDS crisis throughout. And now, I would call us the queer church.”

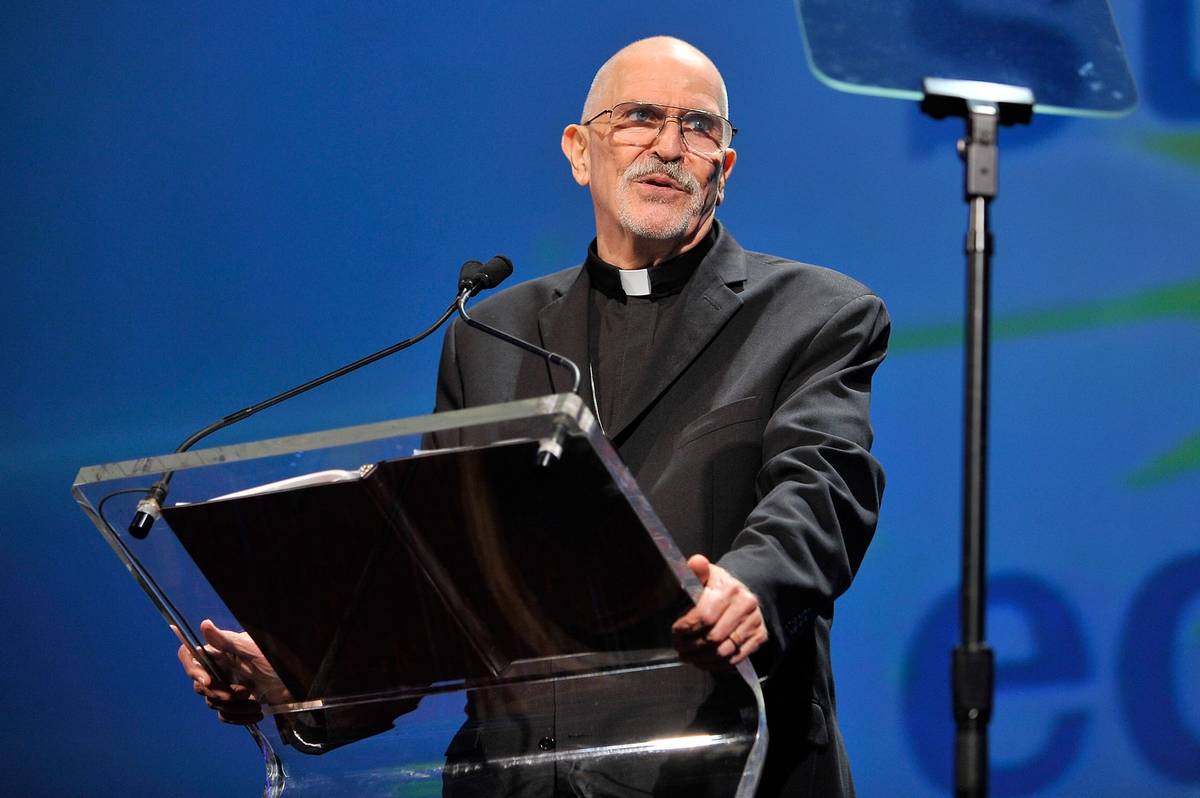

Perry speaks during PFLAG National’s Straight for Equality Awards Gala, New York, 2012D Dipasupil/WireImage

Perry says if he could distill MCC’s mission today down to a slogan, it would be: “Salvation = Liberation.”

“Jesus brought us liberation,” he said. “We can be ourselves.”

According to Amos, MCC’s place is on the margins. “I would say that MCC welcomes the fringe,” she said.

Among mainstream Christian churches, even the more affirming denominations that officially welcome LGBTQ members, still place an emphasis on conforming and fitting in, Amos said. “If you’re polyamorous, if you’re trans—there are multiple ways that people are marginalized—then you don’t fit in as well,” she said, noting that the bias in those churches often still skews toward white, married or partnered, and upper-middle-class membership.

Currently and going forward, Amos said that ministry to the margins for MCC means an intersectional approach that includes race, “trying to understand our own racism, the racism in society. The intersection of oppressions—that’s our conversation that we’re having, and I think, probably, our edge.”

She speaks of MCC churches in the U.S. that, while not the majority of their churches, have primarily Hispanic congregations, while others would identify as falling more within what she calls the “Black church tradition.”

For Perry, ultimately, identity is rooted in something he preached in his first MCC sermon: “We must be humble, spiritual human beings first, homosexuals second.”

It’s a message he stands by. “I always tell people that for me, you’ve got to do those two things,” he said, “That all of us, every human being, has to come to terms first with our spirituality. We’re spiritual beings created by God, I really believe that. And I say to people, that that part of our spirituality is to know without a shadow of a doubt we are children of God.”

He speaks of the “revelation” that led to MCC’s founding, the “still small voice of God speaking to me in the mind’s ear, and saying to me, ‘Troy, I love you.’”

When he protested, insisting this wasn’t possible—Perry speaks of “arguing with God, telling God, ‘You can’t love me, I’m still a homosexual,’”—he said, “God said to me in that still small voice, ‘Troy, don’t tell me what I can and can’t do. I love you and I don’t have stepsons and daughters.’”

“And with that,” Perry said, “I knew that I could be a Christian and I could be a spiritual person. More important to me than anything. It took me three months before it dawned on me, wait a minute, God loves me, then God has to love other gay people. And that’s the foundation stone, that revelation of Metropolitan Community Church.”

“It still resonates in our denomination,” he said, “We have a foundation and that foundation works, and it has for over 50 years.”