Rediscovering My Judaism—in Africa

I went to Ghana to study drumming. But I learned much more about the religion I’d cast aside, including how to reclaim it.

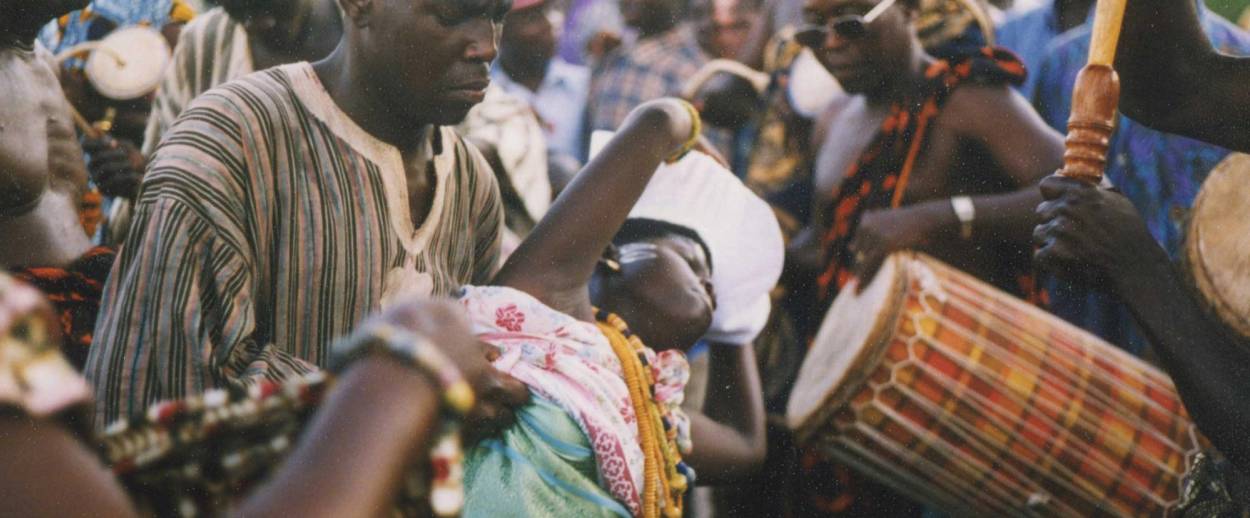

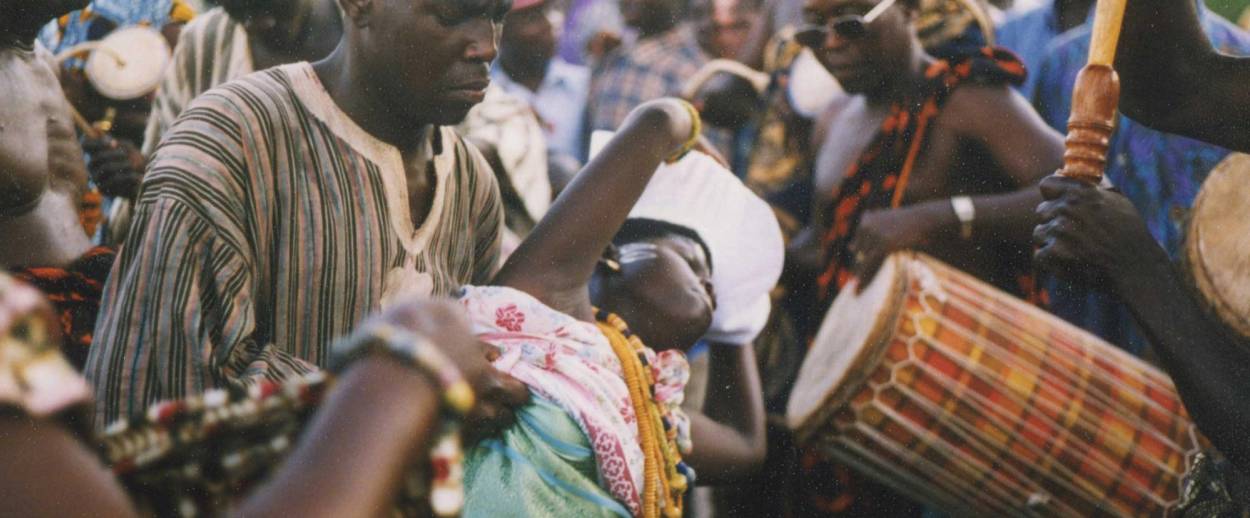

Just after we got married in 1997, my wife Ingrid and I traveled to Ghana on an extended musical honeymoon, to study a style of traditional West African drumming performed by an ethnic group known as the Akan. Four years earlier, while still single, I’d joined a drumming troupe in Toronto made up of Akan immigrants, led by master drummer Kwame Obeng. Before he returned to Ghana, Kwame invited me to train with him there, where he led a royal drumming ensemble in the court of an Akan chief. A few years later, I met Ingrid, a professional percussionist who was as excited to go as I was.

While we stayed in Ghana for four months, the honeymoon ended almost immediately—and not just because we both got sick. (Ingrid suffered a near-fatal case of amoebic dysentery, while I acquired something that looked suspiciously like malaria.) The rhythms we were expected to play with the royal drummers—at funerals and festivals, for massive crowds of dancers and chiefs—were fiendishly difficult, and neither Ingrid nor I could figure them out at first, resulting in a lengthy series of botched performances and public humiliations.

But if the drumming proved challenging, it was the locals’ religious practices that were the most difficult for us to endure. Little did I know that these rituals—some of them too bloody for us to watch—would have a profound effect on me, bringing me back to the Judaism I’d cast aside years before.

***

As a child, I attended an Orthodox Jewish day school, went to Saturday morning services, and idolized the rabbis at my family’s synagogue in Montreal, picturing them in my mind’s eye as cartoon superheroes who wore yarmulkes and tallitot rather than capes and masks. My understanding of Judaism wasn’t terribly sophisticated, and I accepted most of what I was taught—the stories of miracles and divine intervention, of Joshua at the battle of Jericho and Jonah in the belly of the whale—as God’s own truth.

At some point, however, doubt began to creep in. It became increasingly difficult for me to reconcile what I learned from my Torah and Talmud instructors, many of whom insisted that the Earth was just over 5,700 years old, with what I learned in my physics and biology classes. By seventh grade, I was getting into heated arguments with my homeroom teacher, an Orthodox shaliach, or emissary, from Israel, about the theory of evolution. (I believed in it. He did not.) I thought that I had to choose between one set of beliefs and the other, and I did, giving up on Judaism as a matter of faith and practice in the process.

Instead, I embraced the rational empiricism embodied by my new scientific heroes: men like Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein, who, unbeknownst to me at the time, held fairly complicated attitudes toward religion. (Both gradually moved toward agnosticism, with Einstein attesting to a fascination with the pantheism of the Dutch Sephardic philosopher Baruch Spinoza.) To me, if you couldn’t prove something by scientific means—and if your only support for an idea boiled down to some nebulous concept of faith—it might be a comforting fairy tale, but it had little to offer a thinking person.

As a result, by the time I reached adulthood, I had thoroughly rejected Judaism as a religion while remaining deeply attached to it as a culture—a situation that would later prove deeply puzzling to Ingrid, a convert to Judaism who couldn’t understand how I could cast aside such an important part of my Jewish identity while still identifying so strongly as a Jew.

In a perversely self-righteous twist, I also convinced myself that by going secular, I was repudiating the prejudices of my observant peers, many of whom spoke disparagingly of goyim and railed against Arabs. Yet despite that consolation prize, I spent years feeling intensely conflicted about my decision. Turning my back on my religion seemed like the only principled move I could make, but it also left a void that I could not fill. I called myself an atheist and shunned any ritual that invoked an imaginary Supreme Being—but I wasn’t exactly happy about it. Come Yom Kippur, I was more than likely to be found lurking in the precincts of the nearest synagogue, straining to hear the sounds of Kol Nidre without actually having to participate in the service.

So it came as something of a shock to realize on that trip to Ghana that I needn’t have tossed my Judaism aside at all.

***

The Ghanaians I knew in Toronto never talked about their religion, at least not in a language that I could understand (I only developed a rudimentary grasp of the Akan language, known as Twi, later on). No one ever slaughtered a sheep at any of our performances in the greater Toronto metropolitan area. Scholarly references to “ritual offerings” by the Akan, meanwhile, were vague and gave the impression that such things were confined to the past.

They were not.

For many of the people we met in Ghana, animal sacrifice remained an important way of honoring the ancestors, those deceased relatives who continue to watch over their kin from the afterlife. It was also a central part of just about every traditional religious ritual we observed—and we observed a lot of them, both as spectators and as performers. Whatever the occasion, chances were good that one or more sheep (castrated rams were the preferred item on the menu) would buy the farm.

To us, the practice was profoundly disquieting. Ingrid loves animals: She rides horses, adopts cats, and feels a deep sense of compassion for all living creatures. I, meanwhile, am profoundly squeamish: I can’t even watch a medical drama on TV without burying my face in my hands, terrified that I might see fake blood gushing from a fake wound.

The manner of execution didn’t make things any easier. The sheep typically had their throats slit with an implement resembling a blunt letter opener, and it took an agonizingly long time for them to die. At one ceremony, the still-breathing victim was held over a ritual bonfire, its blood spattering and sizzling on the flaming logs below, before it was finally dumped in a corner.

To someone who grew up davening and wrapping tefillin, this was all rather hard to take. I’d studied the Hebrew texts that described how the Israelites of the Old Testament sacrificed animals at the temple in Jerusalem and how they cooked and ate some of their offerings—including, of course, the paschal lamb—just as the Akan continue to do. (More than 200 years ago, the British abolitionist and former slave Olauda Equiano, aka Gustavus Vassa, noticed the same similarity between the Jews of the Bible and his own people, the Igbo of Nigeria: “Like the Israelites … we had also our sacrifices and burnt offerings.”) But that was ancient history to me, something that I understood only in the abstract. The Passover offering, for instance, is now represented by nothing more than a roasted lamb shank on a Seder plate—a neat and tidy tribute to what was once a far more sanguinary practice. Aside from kosher butchering, which no one but kosher butchers normally gets to watch, circumcision is the goriest ceremony left in Judaism, and it’s administered with a lot of medicinal Manischewitz.

Our Akan hosts had no trouble embracing an astonishing array of seemingly incongruous religious practices. Most of the people we met identified themselves as Christians, but that didn’t stop them from partaking of traditional Akan religion and all of its accoutrements: not just blood sacrifice, but also the scores of gods who inhabit trees and rocks and rivers, the shrines and talismans known as fetishes, ancestor worship and spirit possession—all of the so-called heathen practices, in other words, that the Christian missionaries who came to the region in the 19th century tried to stamp out. One of our friends, a court official named Esiedu, was both treasurer and choir director at the local Presbyterian Church. But he also spent a good deal of time communing with the ancestors and presiding over ritual sacrifices at the palace of his chief. If I close my eyes, I can still see him dancing through a puddle of sheep’s blood during an Akan holy day, vermilion droplets splashing everywhere, a serene smile on his face.

At first, we couldn’t figure out how Esiedu and our other Akan friends could be so heavily invested in Christianity and also in something else entirely. How could they hold both of those belief systems in their heads at the same time? After a while, however, we came to the conclusion that they simply had a much more accommodating view of religion than we did. It didn’t have to be an exclusive, either/or kind of deal. Instead, it could be an inclusive, both/and sort of arrangement. They also had a knack for interpreting the various elements of their syncretic religious system in ways that kept the cognitive dissonance to a minimum.

“Do you believe in Jesus?” I once asked a drummer in the royal ensemble.

“Oh, yes,” he said emphatically, his eyes wide. “Jesus died for us, just like the ancestors.”

At the time, I couldn’t make heads or tails of that response. I’d been raised to understand my own religion in a particular way: Jews did this, they believed in that, and some things just weren’t kosher. That was, in large part, why I had walked away from Judaism as a form of organized religion; I figured that if I couldn’t square my religious training with the rational, empirical outlook I’d adopted, then I had no alternative but to wash my hands of it altogether. Paradoxically, I persuaded myself that by doing so, I’d also evolved to a higher state of being, one characterized by a more enlightened and tolerant mindset.

Only I hadn’t, and our time in Ghana proved it. As far as I could tell, the Akan we met had genuinely achieved the kind of flexible and inclusive attitude I smugly imagined that I’d espoused, but which had in fact eluded me. And they hadn’t had to abandon their own traditions in order to do it. Instead, they took what appeared to be mutually exclusive ideologies and treated them like pieces of a larger puzzle, fashioning what was, to them at least, a thoroughly coherent worldview—an act of intellectual and philosophical jujitsu that left me feeling both chastened and inspired.

***

Seeing the Akan harmonize all of those seemingly incompatible ideas made me wonder if I’d been too quick to throw the baby out with the bathwater when it came to my own religion. Maybe there was a way to reconnect to the spiritual side of Judaism without violating my intellectual principles; maybe I could re-engage with something that had once given me a sense of the numinous and a connection to a larger Jewish community without feeling like a hypocrite.

I spent years grappling with those questions, test-driving synagogues of various denominations, and talking with Ingrid about what Judaism meant to me, what it meant to her, and what it ought to mean to us as a couple, with Ghana as background music. In 2005, however, life upped the ante and lent a newfound sense of urgency to that exploratory process when Ingrid and I had our first child. Three years later, we had another; and as our sons learned to walk and talk, I found myself wondering how I was going to introduce them to their Jewish heritage in a way that wouldn’t shortchange them, or make me cringe.

With all due respect to Richard Dawkins, I have moved away from the idea that science and religion are necessarily incompatible and toward the position that they are different yet complementary ways of apprehending the world—each concerned with its own realm, each with its own strengths and limitations.

For example, I’m now willing to view the tales I was taught in Hebrew school as metaphors to be plumbed for meaning, rather than as mere claptrap; and although the anthropomorphic, personal God of the Old Testament still seems to me a rather naïve, childlike concept, as Einstein himself put it, I now describe myself as an agnostic, as both he and Darwin did at the ends of their lives, rather than as an unabashed atheist. While my faith in understanding physical reality through rational, empirical means remains unshaken, I’m prepared to accept more ineffable forms of experience as well, and to acknowledge that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in any single philosophy.

As a result, I’ve been able to reconnect with the spiritual aspects of Judaism without suffering a complete mental breakdown. I can’t say that my rapprochement with Judaism is complete; I am, after all, a middle-aged man, and any personal renovation project is going to be slow-going. But if my return to Judaism remains a work in progress, progress has nonetheless been made.

By mutual consent, Ingrid and I have enrolled our two young sons in a Sunday school program at the Free Synagogue of Flushing; we all attend services there on a regular basis; and I am once again part of a Jewish community, one that is as welcoming and inclusive as any I could have wished for. Not for nothing, it’s led by Rabbi Michael Weisser, a man who once converted a former Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan. For a guy like that, handling a prodigal like me must be a walk in the park.

I even recently led a Passover Seder in our Queens apartment and helped lead another hosted by friends in Washington, D.C., reaching back into the store of Jewish knowledge that I once assumed would remain buried forever in the furthest recesses of my mind. Excavating that material wasn’t without its complications; I still clench up, for instance, whenever I recite Hebrew prayers addressed to Our Lord, King of the Universe. But I was happy to explain the symbolism of the Seder plate, to tell the story of the Exodus, and to raise questions about what it meant for the God of our fathers to have slain the firstborn children of the Egyptians, and to have drowned Pharaoh’s army in the Red Sea—a spirit of critical inquiry that is, after all, as central to Judaism as any particular belief.

As a consequence, I feel like I’ve come nearly full circle, returning to my roots after a long period wandering in the desert. All it took was a trip to West Africa, some rueful self-reflection—and a whole lot of sheep’s blood.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Alexander Gelfand is a recovering ethnomusicologist, a sometime jazz pianist, and a former West African drummer. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Forward, and elsewhere.