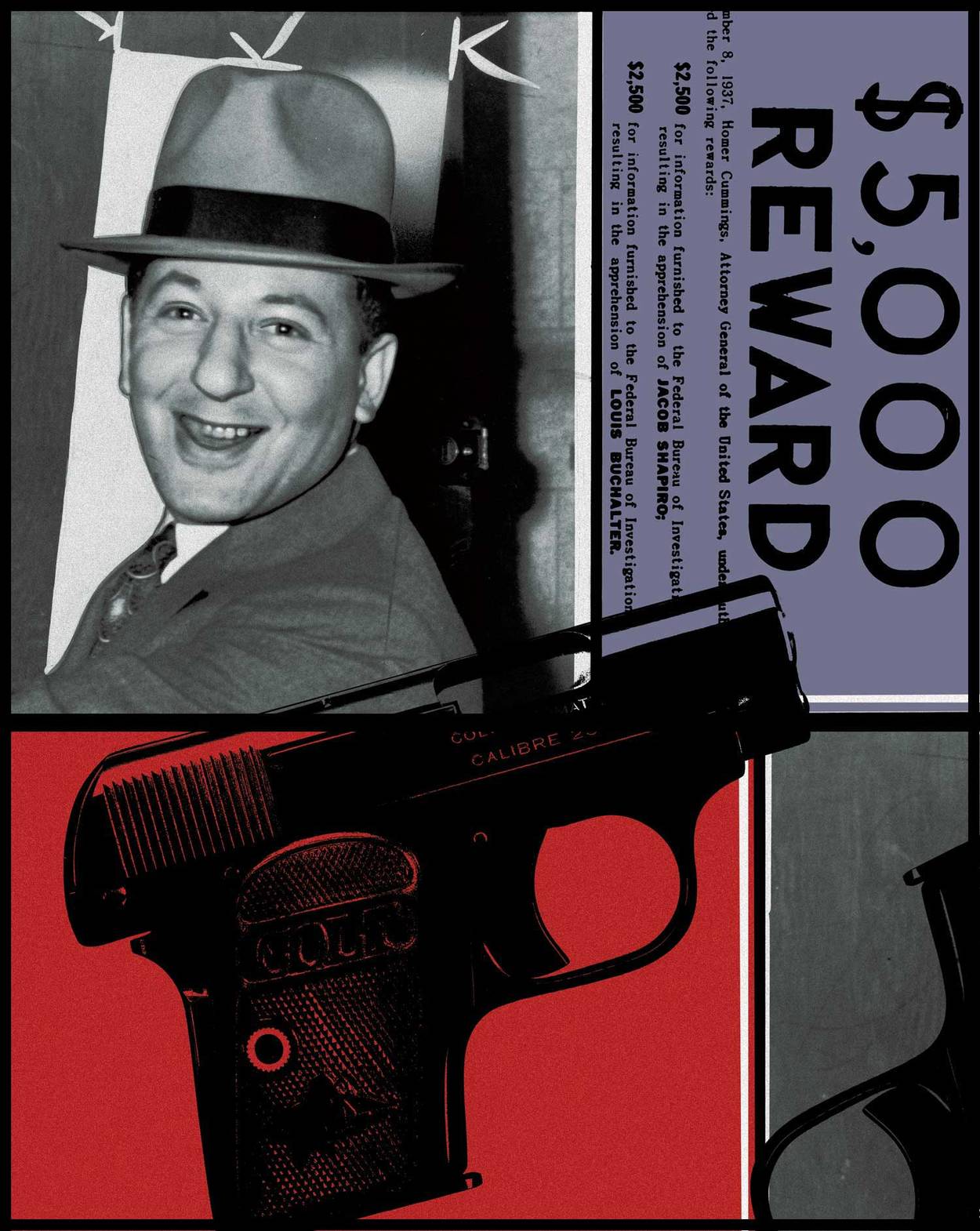

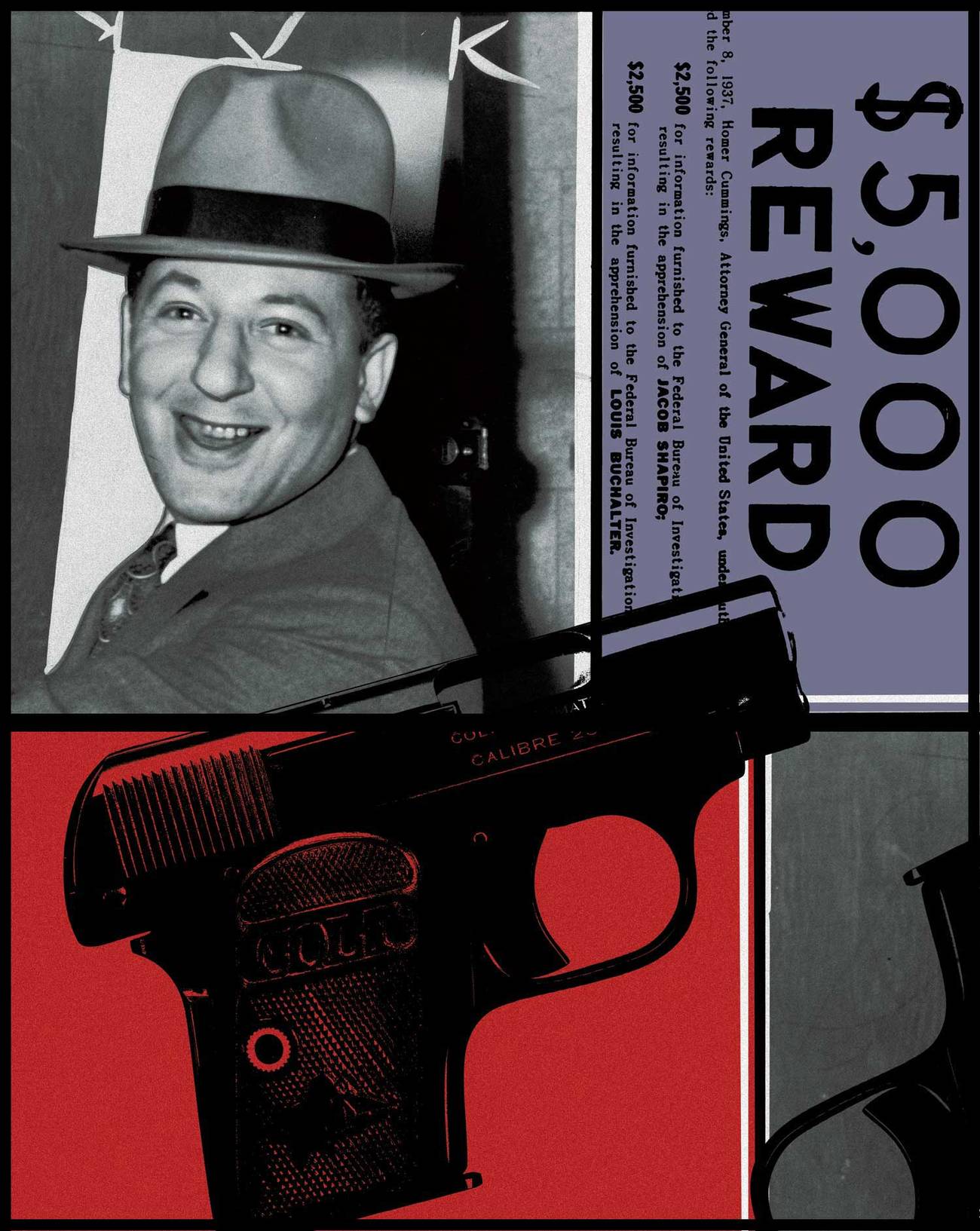

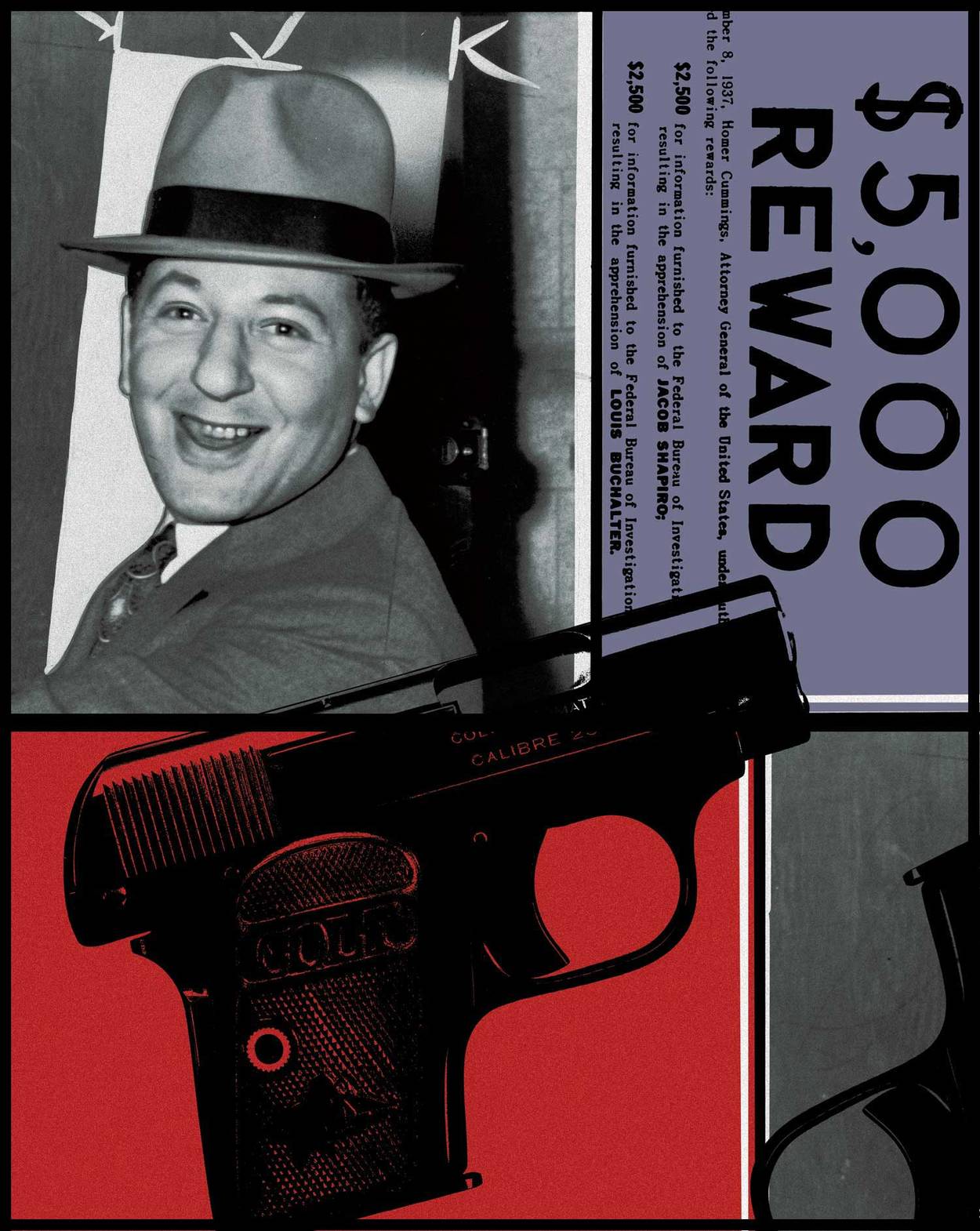

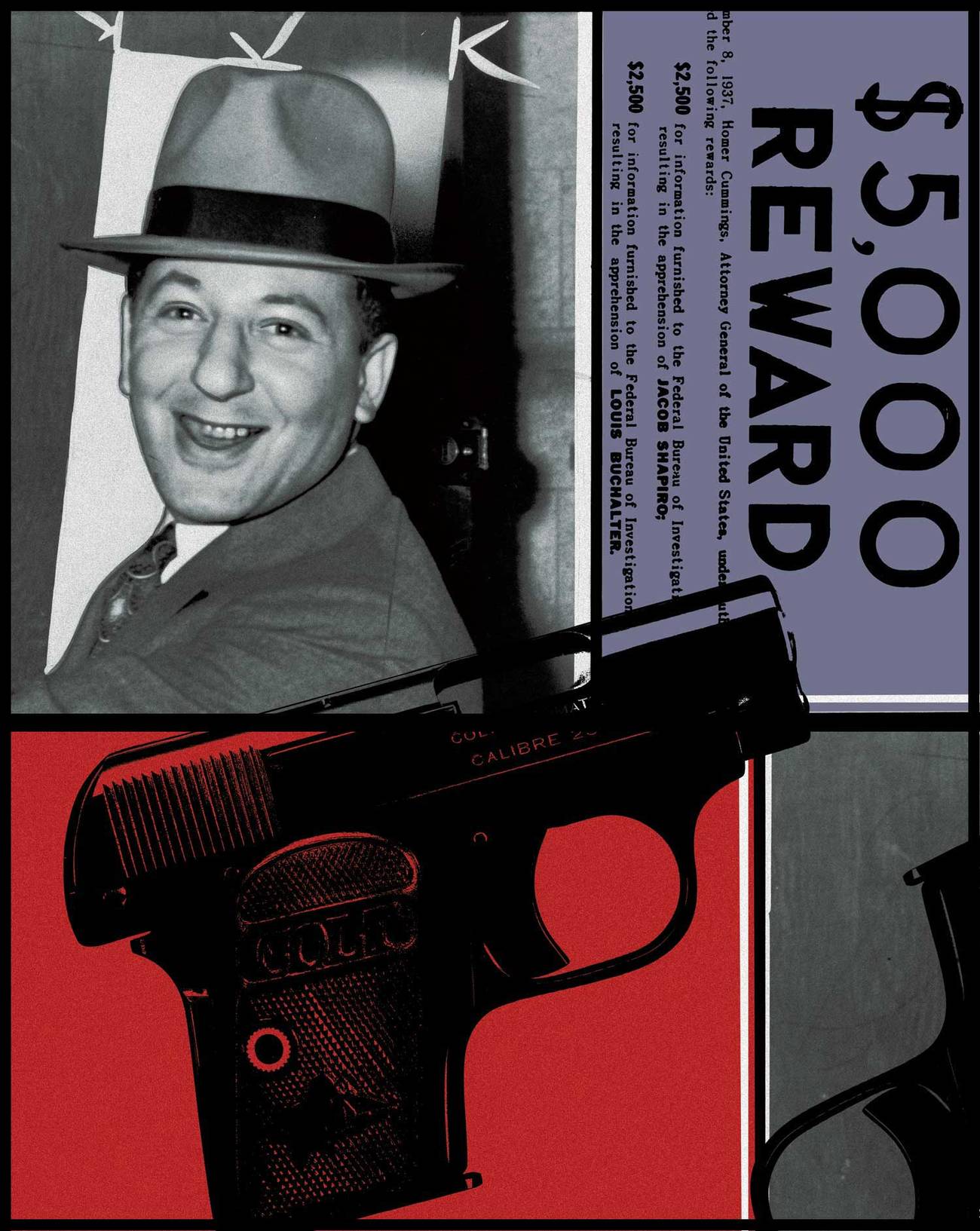

The Ruthless Racketeer

In the annals of crime in New York City no one was feared more than Louis ‘Lepke’ Buchalter, who ordered the murders of dozens of men

Original photo: Library of Congress

Original photo: Library of Congress

Original photo: Library of Congress

Original photo: Library of Congress

The conviction of Louis Buchalter assures the public of permanent protection against one of the most powerful and dangerous rackets leaders this country has ever known.

—Thomas Dewey, District Attorney of New York County, March 2, 1940

To his adoring Jewish mother, Rose, he was “lepkeleh,” her “little Louis.” But to most everyone else in New York City and beyond, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter was the most ruthless racketeer and gangster to emerge from the Lower East Side, a mob leader who terrorized countless industries and ordered the murders of upward of 50 people who dared to defy him or whom he decided he could no longer trust. In 1935, Lewis Valentine, the New York City police commissioner, rightly described Lepke, as he was known, “as among the nine most notorious and dangerous criminals” in the United States.

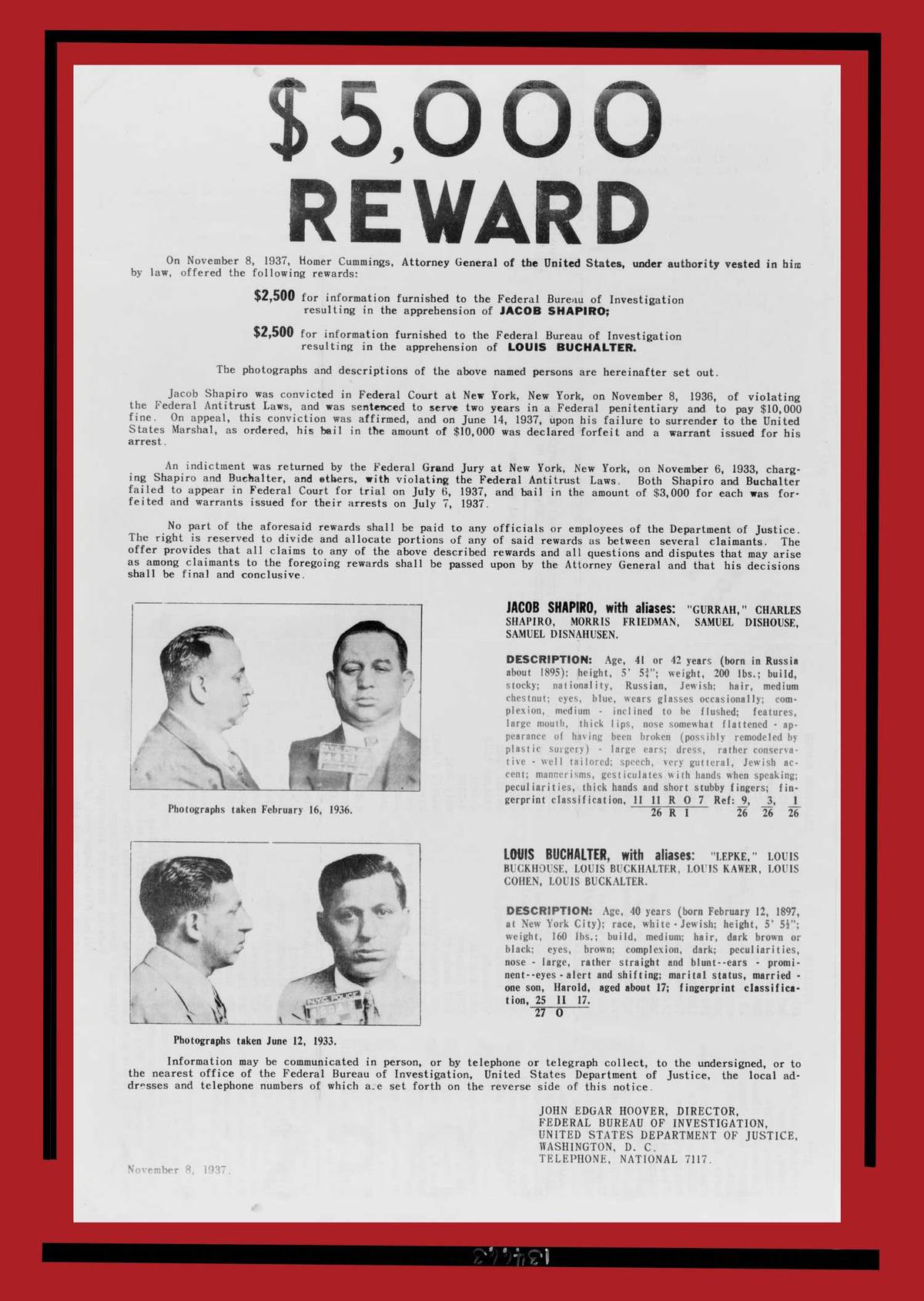

At the height of his reign, Buchalter and his chief partner in crime, Jacob “Gurrah Jake” Shapiro, were taking in more than a $1 million (about $22 million or more today) annually, and dominated, if not outright controlled, the garment, leather, fur, baking, and trucking industries in New York and parts of New Jersey. Shapiro’s nickname was said to have derived from his younger days when he stole from East Side peddlers. In broken English, the Yiddish-speaking peddlers yelled at him, “Go away Jake,” which according to his hoodlum friends, sounded like “Gurrah Jake.”

Lepke, who favored a fedora, was of medium height and never dressed flashy, though he and his wife, Beatrice (Betty), who were married in 1931, and her son Harold (a child from her first marriage whom Lepke adopted) lived in luxurious apartments facing Central Park, drove a large black automobile, and enjoyed holidays in Europe and elsewhere. Shapiro, on the other hand, was boisterous, rude, and stocky. Lepke rarely raised his voice, yet their gang of sluggers, thugs, and killers, who called him “The Judge” or “Judge Louie,” feared him more than they did Gurrah. As one of their men, Sholem “Sol” Bernstein, put it: “I don’t ask questions, I just obey. It would be … healthier.”

The son of Rose and Barnett Buchalter, poor East Side Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire, Louis was born in New York City in mid-February 1897. Both his parents had children from other marriages and by the time Louis and two other siblings were born to Rose, they were a family of 13. For a time, they all lived in a tenement on Essex Street near Delancey Street but moved around a lot. Barnett ran a small hardware store in a shop on Henry Street, yet barely made a living. The children, including Louis, went to public and Hebrew schools. Louis’s elder half-brother became a rabbi and another a dentist. His sisters married and had their own families.

Barnett’s death in November 1910, following a diabetic coma, was hard on Rose, who tried to make money selling food to her neighbors. In 1912, Rose left Louis and the other younger children in care of his older half-sister Sarah, while she spent part of the year in Arizona or Denver, where one of the sons lived. Perhaps his mother’s absences were the reason Louis soon got into trouble as a young teenager, or maybe it was his interaction with other East Side street kids. Either way, once Louis’ life of crime started, it did not end for the next three-and-a-half decades.

He stole fruit from peddlers and was soon burglarizing tenements. In September 1915, when he was 18 years old, he was arrested and charged with theft and assault, but the case was dismissed. The following year, using the alias Louis Kauvar (one of dozens of aliases he used over the years; Kauvar was the surname of his mother’s first husband), Buchalter was arrested in nearby Bridgeport, Connecticut—where he was living with an uncle—for stealing a salesman’s suitcase. For this, he was sent for a year to the State Reformatory at Cheshire.

Back in New York City, he and Shapiro, who was born in Odessa in 1899, became close friends and soon forged a criminal alliance. They spent time in the Brownsville area of Brooklyn, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, where they harassed pushcart peddlers. By late 1917, both of them were sent to Sing Sing for the first but not the last time on grand larceny convictions. After transfers to Auburn Prison and then Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York, Buchalter was released in early 1919. He was subsequently arrested a few months later on an attempted burglary charge, yet was once more discharged. In January 1920, he was arrested again for burglary of a women’s clothing store and was sent back to Sing Sing for another stint of two-and-a-half years.

Once he was released in March 1922, he and Shaprio, who had been out of prison since 1919, sought a new way to make money by doing what Dopey Benny Fein and others had done: acting as thugs for garment unions and manufacturers. They were soon known as “Lepke and Gurrah” or “L and G.” Not content with merely being a shtarker or strong-arm, Lepke was devious in his approach. While much has been written about their clever criminal schemes, at its most basic the duo of “L and G” were essentially notorious extortionists. They infiltrated and controlled unions, installing their own men in key positions, and dictated trucking and distribution for an assortment of industries, often driving competing firms out of business. Yet, mostly they demanded regular hefty payments disguised as dues. In 1932, when they tried to take over the fur-dressing business, they set up the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation and the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation. Their objective was to eliminate all companies and dealers who refused to become members. Of course, the only threat to these businessmen and workers came from “L and G,” who blackmailed the associations’ members for hundreds of thousands of dollars or charged them for protection—from members of their own gang—or to stop a strike, which they would make happen. As the FBI later reported, the dealers and manufacturers in the fur-dressing as well as other industries who defied them were threatened with violence, had acid thrown on their merchandise or in their faces, had their shops and plants firebombed, and in some cases, were murdered. These deeds were handled by Lepke and Gurrah’s small army of thugs—estimated in May 1935 to be 250 strong-arm men, who did their bidding eliminating opponents and enemies, if necessary.

In October 1927, a falling out over doing business in the garment industry with fellow gangster and onetime ally Jacob “Little Augie” Orgen (Orgenstein), the 34-year-old son of middle-class Jewish immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, led to an order given by “L and G” to get rid of him. During the early 1920s, Orgen had established himself, if briefly, as a powerful East Side gang leader (and bootlegger), who accepted strong-arm contracts mainly from union leaders. He did not hesitate to back up his position with street gunfights that targeted and eliminated his rivals who cut into his revenue. (For several years, Orgen’s chief nemesis for strong-arming was Nathan Kaplan, known as “Kid Dropper,” who was murdered in August 1923, possibly on Orgen’s order.)

Library of Congress

One evening, as “Little Augie” was walking down Norfolk Street on the East Side, guarded by Jack “Legs” Diamond, three men shot at them. Orgen was killed instantly, while Diamond survived, yet he refused to tell the police who the assailants were. Further investigation led the police to believe that the “hit” had been ordered by Lepke (who the authorities identified as Louis Buckhouse) and Gurrah because of a “business quarrel,” as the Times described it, over the settlement of a strike. Orgen wanted to end the strike for a fee of $50,000; Shapiro was insistent that the strike continue so that payment for strong-arming services would keep flowing. Buchalter and Shapiro surrendered to the police, but were not charged with the killing because of a lack of evidence and no corroborating witnesses.

Beyond racketeering, Buchalter’s other so-called claim to fame was that he was one of the founders of Murder, Inc., or what the press at the time referred to as the “murder ring” and a “murder-for-cash syndicate.” It was a centralized system to coordinate contract “hits” by using gunmen—mainly Jewish and Italian gangsters—with no affiliation to those who were killed, thereby protecting the gangster head who had given the order for the murder. Justice officials believed that from 1929 to 1941, Murder, Inc. was responsible for close to 400 murders and likely many more. Besides Lepke, the leaders of Murder, Inc. were Abe “Kid Twist” Reles and later Albert “The Mad Hatter” Anastasia. (Anastasia attended the bar mitzvah of Lepke and Betty’s son Harold, as did Lucky Luciano and Louis Capone—no relation to Al Capone—among other New York City gangsters.) The headquarters of the Jewish section was at Mrs. Rosie Gold’s Midnight Rose Candy Store located on the corner of Saratoga and Livonia avenues in Brownsville.

A key Murder, Inc., assassin was Harry “Pittsburgh Phil” Strauss, who murdered upward of 100 men. Paid a salary of least $125 a week, his preferred weapons included guns, ice picks, and garrotes. Following an arrest and trial, Strauss was executed in Sing Sing’s electric chair in June 1941. One of Murder, Inc.’s most legendary actions took place in October 1935 when Charles “Lucky” Luciano and other mobsters decided that bootlegger Dutch Schultz could not be allowed to kill Thomas Dewey, then a New York special prosecutor investigating corruption, as he declared he would. Luciano believed that such an act was foolish and dangerous and would lead to even more legal trouble for the mobsters. Buchalter was allegedly assigned the “task” of taking care of Schultz, who was shot at a Newark restaurant on Oct. 23, 1935, and died the next day.

Another individual Lepke decided had to be “dealt” with was a local New York small-time businessman named Joseph Rosen. Not only was Rosen, 46 years old, murdered in September 1936, but his killing also proved to be Buchalter’s undoing, a fateful decision that ultimately ended his life, too. In the early 1930s, Rosen was a partner in a medium-size New York City clothing manufacturing company and also owned several trucks for the distribution of the goods. Refusing to fork over his hard-earned money to Buchalter and Shapiro, his machinery, including his trucks, was repeatedly vandalized and he was threatened on many occasions. Early in 1933, Rosen’s son Harold recalled witnessing a heated discussion between his father and the usually calm Lepke. He later testified that Buchalter “pushed his face within six inches of my father’s face,” who returned to the office “white” and “shaken” from the intense conversation. Six months later, unable to withstand the threats, Rosen’s company went out of business. Trying to get back on his feet, Rosen eventually opened a small candy and newspaper store and started saving money with a plan to restart a garment trucking company.

In 1935, when New York Gov. Herbert Lehman appointed Dewey as a special prosecutor to investigate rackets and racketeers undermining New York’s various industries, a rumor circulated that Rosen was going to offer incriminating information about “L and G’s” criminal operations. Whether the rumor was true or not is unknown, though Dewey later denied that he knew Rosen or had spoken to him. Even if Rosen wanted to cooperate with Dewey’s investigation—a few weeks before he was killed, Samuel Levine (no relation to the author), a business agent and former president of a local clothing drivers union, urged Rosen to remain silent—he never got a chance to do so.

It was later revealed by one of Buchalter’s former gunmen, Max Rubin—who survived an attempted assassination after Lepke decided that Rubin was a liability—that Lepke had ordered a “hit” on Rosen. Early on the morning of Sept. 13, 1936, as Rosen opened his shop, three or four gangsters opened fire on him, shooting him 15 times and killing him. For several years, the murder went unsolved, until federal and state justice authorities came after Buchalter and Shapiro.

In November 1933, federal officials launched a huge legal case indicting five labor organizations, 68 corporations, and 80 individuals for violating the Sherman antitrust law or conspiring to do so. The “worst” offenders charged were Lepke and Gurrah, who were accused, along with others, of attempting to prevent fur dealers and manufacturers from conducting business through their bogus Protective Fur Dressers Corporation. For annual payments of $20,000, “L and G” promised “to protect the interests of the fur dressers against undue competition.” The case dragged on for several years and it took until November 1936 to convict the two gangsters. But the two-year sentences and $10,000 fines permitted were a “mere slap on the wrist,” as the presiding judge remarked.

In August 1937, released on bail pending an appeal and with word that Dewey was about to indict them for conspiring to extort money from clothing manufacturers and baking and flour factory owners, the two gangsters, fearing long prison sentences, went into hiding. Despite substantial rewards for information about them, the police could not locate either man. It was speculated in the press that Buchalter had fled to Poland or Palestine (then under British Mandate). In fact, for two years, he never left New York City. He gained weight and grew a mustache to disguise himself and hid out in apartments and rooms in Coney Island and other parts of Brooklyn.

Tired of running from the police, Shapiro surrendered first in mid-April 1938 and was sent to prison to serve his two-year sentence. He was soon convicted of extortion and conspiracy and received a 15-year sentence; he died of a heart attack in prison in June 1947.

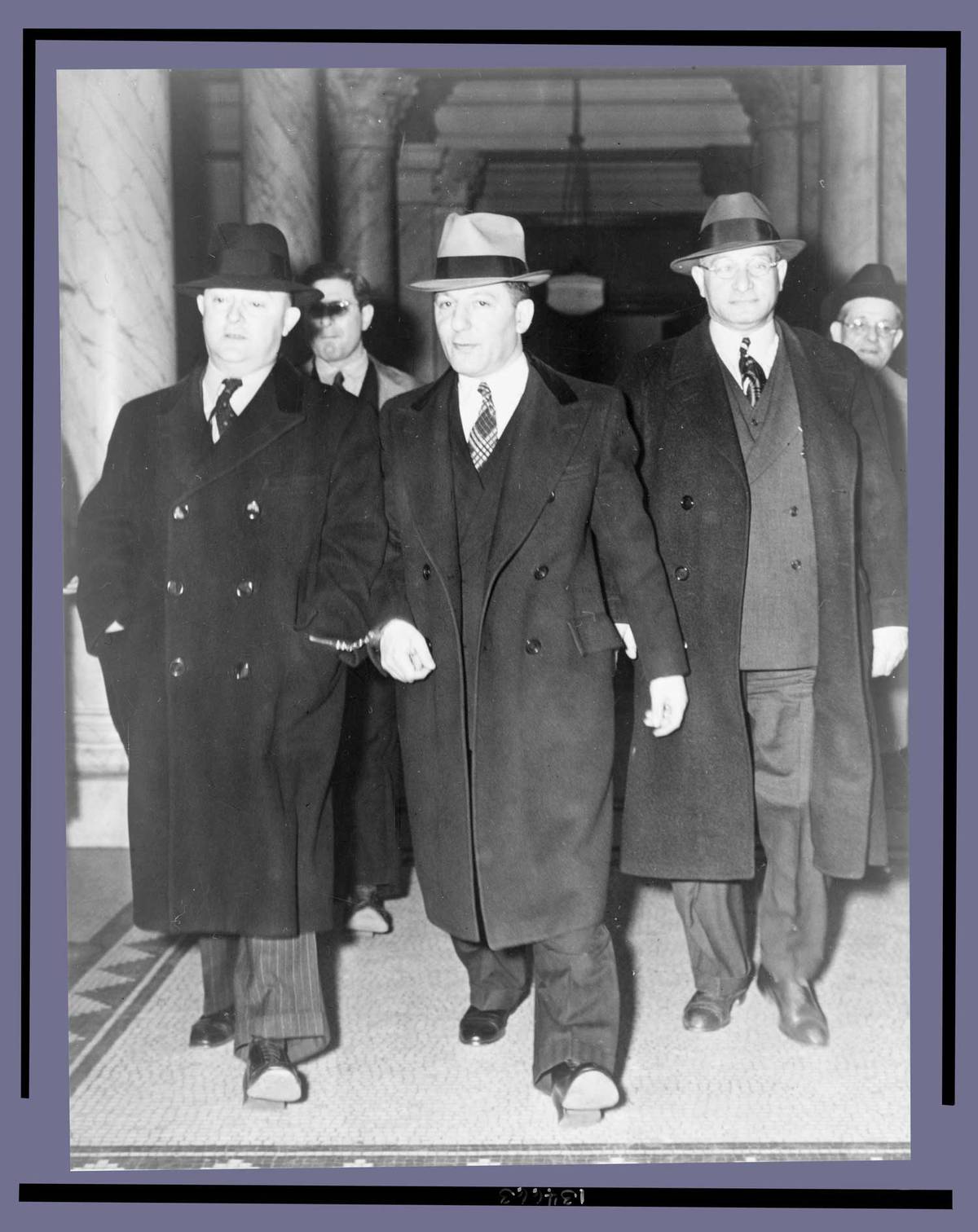

Al Aumuller/Library of Congress

Buchalter stayed hidden until August 1939. Using the syndicated newspaper columnist Walter Winchell as an intermediary, he gave himself up to J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI. Within a few months, he was indicted by federal justice authorities for his part in a massive narcotic smuggling operation. It was alleged that from 1935 to 1937, $10 million worth of narcotics (presumably heroin and cocaine) were transported to the U.S. from Shanghai via Cherbourg and Marseille in France. Several customs agents, who had been paid off and had enabled the shipments to pass easily into the country, were also charged. At the end of 1939, Lepke received a 14-year sentence on the procurement and sale of narcotics and was sent to the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Meanwhile, William O’Dwyer, who was elected district attorney of Kings County (Brooklyn)—and later served as the mayor of New York City from 1946 to 1950—was determined to end corruption and racketeering and take down the murder syndicate. Owing to information provided by Max Rubin and Abe Reles, who after being indicted for murder tried to save himself by becoming a government informant (he later mysteriously died by falling out of a window while the police were guarding him), O’Dwyer had sufficient evidence to charge Buchalter and two of his men with the 1936 murder of Joseph Rosen. In May 1940, the one issue stopping O’Dwyer from proceeding immediately with the case was the intransigence of the federal justice authorities and their jurisdictional power over Buchalter. Months of negotiations followed and finally in mid-May 1941, Lepke was transferred from Leavenworth to the Kings County Courthouse in Brooklyn to be arraigned on the murder charge. According to reporters present in the courtroom, Buchalter was “visibly nervous with a tremor in his voice.”

The trial did not begin until late September. The various witnesses, several of whom like Sholem Bernstein had been members of the murder syndicate, exposed the group’s organizational structure and lethal methods. On Dec. 1, 1942, a jury found Buchalter guilty of first-degree murder and days later, he was sentenced to be executed at Sing Sing in the electric chair. Once again, however, because he was technically in federal custody on the narcotics conviction, the federal government had to agree to turn him over to the state authorities. Moreover, Lepke’s lawyers launched a series of appeals that were seemingly exhausted in mid-February 1943 after the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the murder trial. Then, a month later, in an unusual action, the high court changed its mind and agreed to review Buchalter’s conviction. Another year passed before the appeals ended and federal justice officials consented to transferring Lepke to New York authorities. On Jan. 22, 1944, he was moved to Sing Sing’s death cell and was electrocuted and died on March 4.

Despite being somewhat romanticized in various Hollywood movies—including being portrayed by actor Tony Curtis in the 1975 film Lepke, based on his life—Louis Buchalter should be remembered for what he truly was: a ruthless racketeer and killer. As New York Times writer Meyer Berger wrote the day after the execution in a feature article about Lepke’s criminal exploits, no one will ever know for certain “how many men died on Lepke’s order … They were burned in quick lime, shot, stabbed with ice picks, garroted—all on the orders of the little man with the fawn-like stare and the uneasy diffident front.”

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.