A Safe Haven on the Sea

The surprising journeys that Jewish refugees took to Shanghai to escape the Nazis

Joseph Hant was living a cultured and sophisticated life as a ski jumper and gymnast in Vienna in 1939, with his wife, Ghisela Ellen, and his son Bill, who was 4 at the time. For them, Austria was home. Even after the German annexation of their country the previous year, the idea of emigration didn’t come up for the Jewish family until a close contact in the Nazi party warned Hant that he had to get out. He lined up for days to buy tickets on two of the last ships headed for Shanghai and was finally able to send his family and parents in the summer of 1939—aboard luxury ocean liners.

Hant was among almost 20,000 Jewish refugees who escaped the Holocaust and found refuge in Shanghai. Roughly two-thirds of these refugees came from Austria and Germany, and most others were from Eastern European countries. Survivors and historians have painted vivid portraits of Jewish life in the Shanghai ghetto—squalor, isolation, shortages of food and medicine—but few people know of the curious monthlong journeys that carried tens of thousands of Holocaust refugees to the city in the first place, often in surprisingly swanky accommodations.

In September 1935, the Nazis announced the Reich Citizenship Law, which required that all German citizens have German “blood.” Jews and other ethnic minorities lost their right to vote or to travel, as well as their right to citizenship. Then, in March 1938, the Nazi annexation of Austria extended these same citizenship laws to the 192,000 Jews living in Austria at the time. Kristallnacht occurred just eight months later, and a tsunami of Jews fled the region, seeking refuge in any nation that would take them.

For Jews to be able to leave Germany or an annexed state, they had to show evidence that they would be let into another country, in the form of an official visa and a ticket for transportation. Most countries were unwilling to accept a significant number of refugees, and so the process for obtaining a valid visa was often rigorous and overly bureaucratic. The United States hosted the 1938 Évian Conference to convince other nations to increase their respective immigration quotas, but to no avail. No country other than the tiny Dominican Republic committed to upping its quota. Germany gleefully mocked the conference, remarking on how many countries criticized Germany’s treatment of Jews, but none were willing to take Jews in.

Then there was Shanghai. Shanghai was one of the only free ports that did not require a visa to enter at the time, because the Chinese government had little control over border enforcement. Western imperial forces had established the International Settlement and the French Concession as autonomous foreign areas under unequal treaties, keeping the port open even after the Japanese invasion in 1937. The city was a promising escape for another reason. Ho Feng-Shan, the Chinese consul-general in Vienna, issued thousands of visas to Jewish refugees so that they could cross the Austrian border with proper documentation. The extent of Ho’s rescue only came to light after his death in 1997, and he was posthumously recognized as Righteous Among the Nations in 2000.

For German and Austrian Jews, the typical route to Shanghai formally began in Italy on board Italian or Japanese luxury cruise liners, passing through the Red Sea via the British-controlled Suez Canal, crossing the Indian Ocean and docking in Shanghai by way of India, Singapore, and the Philippines. Around 2,000 Eastern European Jews, mostly Polish and Lithuanian, traveled via the Trans-Siberian train to Vladivostok, where they boarded similar ships to Shanghai via the port city of Dairen (known today as Dalian).

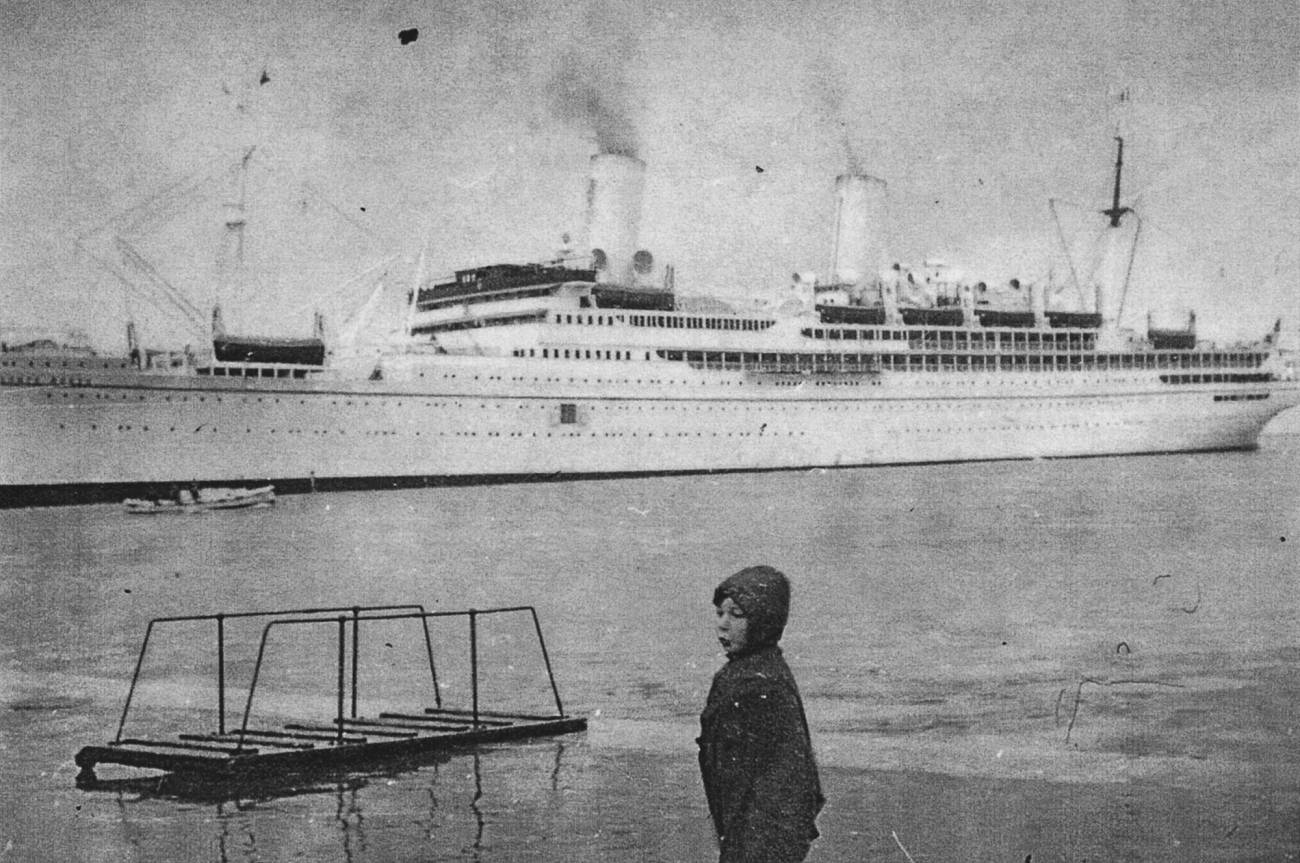

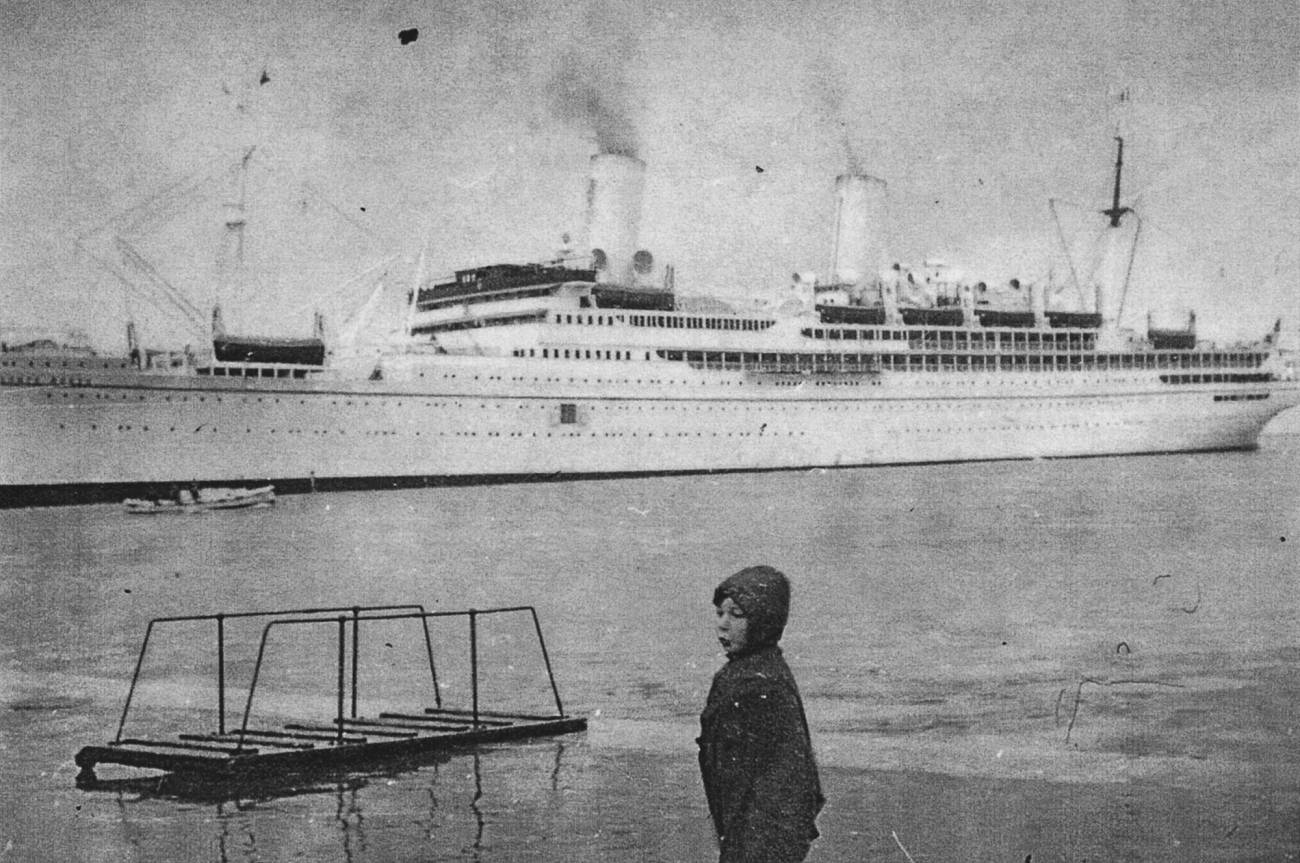

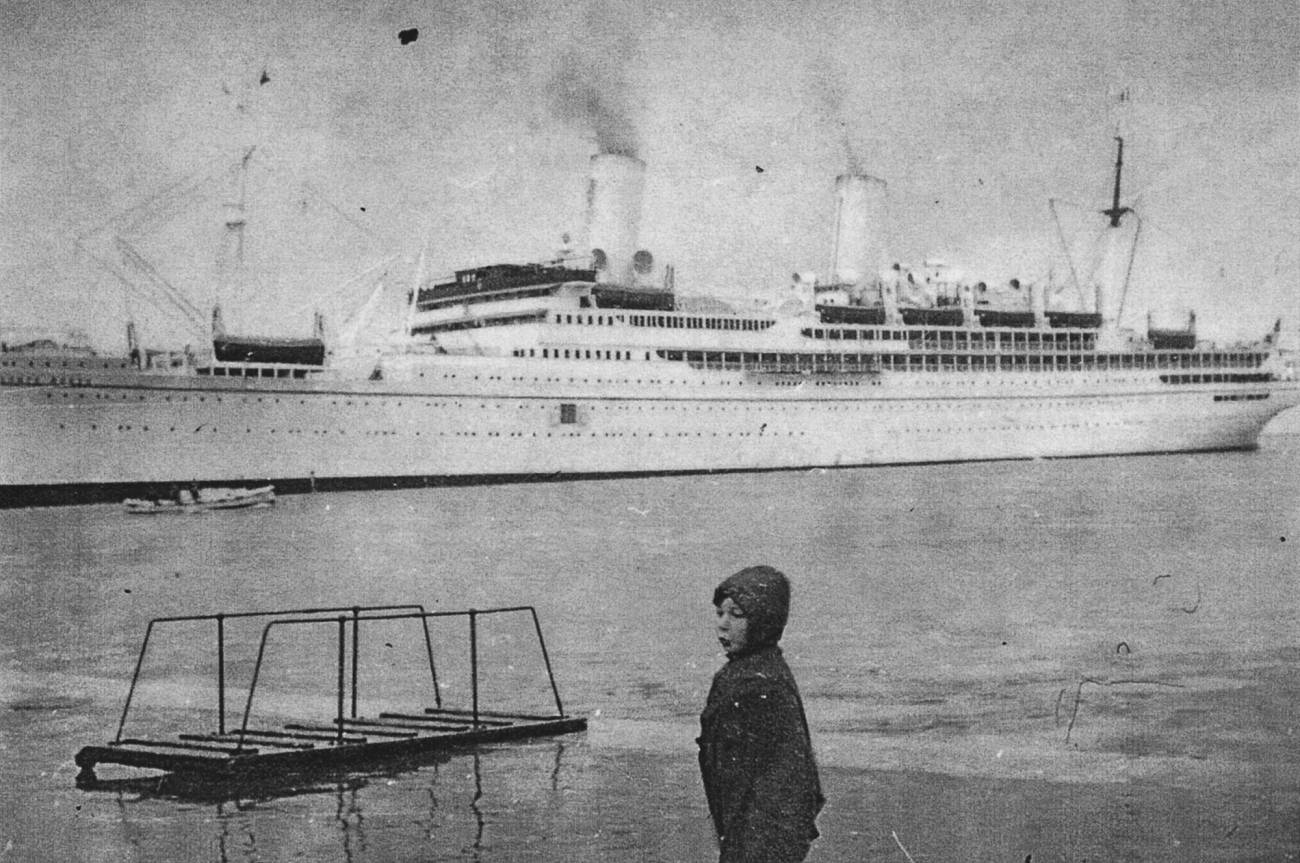

According to survivors’ accounts, the voyage east was a confoundingly luxurious experience. The cruise liners provided three sumptuous meals a day and filled the passengers’ schedule with grand performances and social events. Conte Verde, one of the cruise liners run by Italian shipping company Lloyd Triestino, was a 530-feet-long floating palace. It carried 643 modish cabins, lavishly decorated restaurants and salons, a sun deck, and an outdoor swimming pool. First-class cabins were adorned with sapphire blue carpets, hazelnut furniture sets, and hot water bathtubs. But the 24-day stay came at a steep cost. Many refugees had no choice but to buy first-class tickets due to the high demand. Lloyd Triestino liners like Conte Verde carried more than half of the soon-to-be Shanghai Jews out of Europe, departing from Genoa and Trieste.

Life on the ship was a drastic shift from the turmoil in the distance. Lisbeth Loewenberg, an Austrian refugee who was a teenager traveling with her mother, provided a testimony in Steven Hochstadt’s book Exodus to Shanghai: “You could barely get any food in Vienna anymore, and Jews didn’t get anything. All of a sudden, you were on the ship and you had three meals a day served to you in the dining room of the ship. For me it was a fantastic experience.” Loewenberg witnessed two young men playing the piano and singing pop songs: “I said to my mother, ‘How is it possible that people when they come out from the concentration camp are able to enjoy themselves and sing and be so happy? It seems like a contradiction to me.’ And my mother said, ‘Well, it’s because they came out of the concentration camp that they are happy.’”

Through the eyes of a child, it may have seemed like a grand adventure. But for adults, there were compounding fears, one of which involved money. The Nazis collected large immigration taxes and heavily restricted the amount of cash and assets the refugees could bring with them. Many refugees, including Joseph Hant, left with almost nothing to their names. However, they were allowed to wire some money to the shipping company to be used for goods and services on the cruise liner. From that restriction, a buoyant little economy was born. Luxury goods and services were available to passengers who could afford them, from high-end cigars to onboard gambling. And cash flow worked both ways. The talented 16-year-old refugee Gérard Kohbieter earned money by performing magic tricks around the ship. Passengers also bought expensive souvenirs from the gift shops in the hopes of reselling them for cash in Shanghai.

At its peak, Lloyd Triestino cruise liners, along with Japanese, German, French, and Dutch ships, transported over 1,000 refugees to Shanghai monthly. The voyage was a bubble suspended in the middle of the ocean, briefly sheltering the refugees from the trauma behind and the challenges ahead. In August 1939, the Japanese military authority announced a decree to refuse Jewish refugees, which was soon followed by the Shanghai Municipal Council, the autonomous foreign governing body of the International Settlement. From then on, refugees had to apply for a permit of entry. Ships continued to come in until Italy and Japan joined the Axis powers and the Suez Canal route was cut off. In December 1941, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan blocked any new entrance of Jews into Shanghai.

Under the Nazi allies’ pressure, the Japanese military began consolidating the stateless refugees into what became known as the Shanghai ghetto in 1943. Around 18,000 Jews were forced into a segregated area of less than 1 square mile in the Hongkou district. These former middle-class urbanites were dumped into 10-person rooms where they would face unemployment, starvation, and sickness. The adult refugees had to apply for daily passes at the Japanese police station to leave the ghetto for school or business, which was an arduous endeavor. Joseph Hant was able to establish an electronics shop in the ghetto, fixing radios for money. He welcomed customers from all backgrounds—the European Jews, the Chinese, and even the Japanese. He also joined the guards to patrol the area, along with Japanese soldiers. Survivors of the Shanghai ghetto remember the experience to be extremely dehumanizing, recounting abysmal hygiene conditions and lack of resources that caused 10% of the ghetto population to perish over the entire period in Shanghai.

On Sept. 3, 1945, the Shanghai ghetto was liberated, freeing 15,000 Jews whom the Nazi-allied Japanese forces had cornered. After the war ended, most of the Shanghai refugees left before the new Chinese government was founded in 1949, and by 1958 only around 80 remained. Joseph Hant’s family moved to the U.S. in 1947, where his son Bill earned a Ph.D. from UCLA and became an engineer. At UCLA, Bill would tell his family’s story to visiting Chinese students who had never learned of the Shanghai ghetto.

The narrative of the stately oceanic passage jumps out from the bleakness of the Holocaust. It’s hard to ignore the parallel to the biblical Miriam’s Song of the Sea, sung by the Israelites upon crossing the Red Sea to refuge. With their enemies close behind them and a vast desert ahead of them, they allowed themselves a brief respite to rejoice. The song of the sea is the song that refugees played on the ship’s piano; the song that washed over a young Lisbeth Loewenberg who could not fathom how any joy could be felt amid such tragedy. These refugees had seen death and evaded it. And in the murky sea fog ahead, they saw glimpses of their own liberation.

An earlier version of this story misstated the timing of Joseph Hant’s journey. It was the summer of 1939.

Jacob Fertig is a documentary filmmaker and impact producer based in New York City. He is Co-Founder and Managing Director of Denizen Studios.

Born in Nanjing and raised in Shanghai, Eris Qian is a New York-based writer/filmmaker whose upcoming short film Last Ship East explores the journey of Holocaust refugees on board of a Japanese cruise liner. Her work has been supported by Sundance, Raindance, Women in Film, and Claims Conference.