Signs and Wonders

Making sense of the unexpected messages on billboards and street flyers in Los Angeles

Los Angeles, as befits a city in the desert, is a metropolis of signs. You can find poetry, if not exactly logic, falling like wisteria blooms from personal injury lawyers’ ads: “Jacob—a lawyer—your lawyer.” You can consider actors’ For Your Consideration campaigns for a good two or three years after the awards for the show or movie in question have been given out. Not for nothing did Thomas Pynchon set The Crying of Lot 49 in LA, where if you happen to be looking, you can find your visual field crowded with symbols and scratching open to interpretation.

LA’s billboards can make for some surprising juxtapositions. Recently, a striking image of a delicate, flesh-toned orchid burnished with a dew drop advertised the services of a vaginal rejuvenation clinic on a sign atop Pico Kosher Glatt Mart, a venue noted more for its affordable steam tray khoresh than its steamed labial treatments. Older Persian Jewish women went in and out to buy chicken; I don’t know if any of them glanced up. Farther up on Robertson, there is a billboard with a tagline that sounds suspiciously like a tourism ad or a Star Wars reboot: “Auschwitz: Not Long Ago. Not Far Away.” It turns out to be for an exhibit at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Recently, another billboard on Robertson went up announcing that MOSHIACH IS HERE, only to be replaced a couple of weeks later by one for Disenchanted, the Amy Adams Disney sequel. MOSHIACH made a recent return, and honestly, it’s like he never left—just part of the landscape, like the cast of American Horror Story.

For those who don’t have the resources of a billboard campaign behind them, there is the street flyer. Religious zealotry and flyers share a rich, symbiotic history, going back to the days when Martin Luther handwrote and nailed his theses to a church door. The medieval commentator Rashi’s commentary, too, first appeared in booklets. With contemporary strides in desktop publishing and Scotch tape technology, thousands of proclaimers can bloom in LA like cactus flowers, and the path from something sitting on your chest to getting off it and onto a lamp post is as smooth as the 405.

When I first moved to LA and then when the pandemic limited my options to taking walks around my neighborhood, I would take note of the signs stuck to lampposts. They announced Persian musicians’ tours (SHARAM IS COMING). Some locals put up not-great-but-certainly-sincere poetry tied to the Jewish holiday cycle. One flyer proclaimed in Hebrew the terrible mistake one could make by wearing Nike shoes: Nike is, after all, the Greek goddess of victory. How could a believer wear such idolatrous shoes on their feet? It struck me as unfortunate that the people most receptive to this message were also the ones most likely to benefit from a brisk jog, but I don’t know how successful this campaign was.

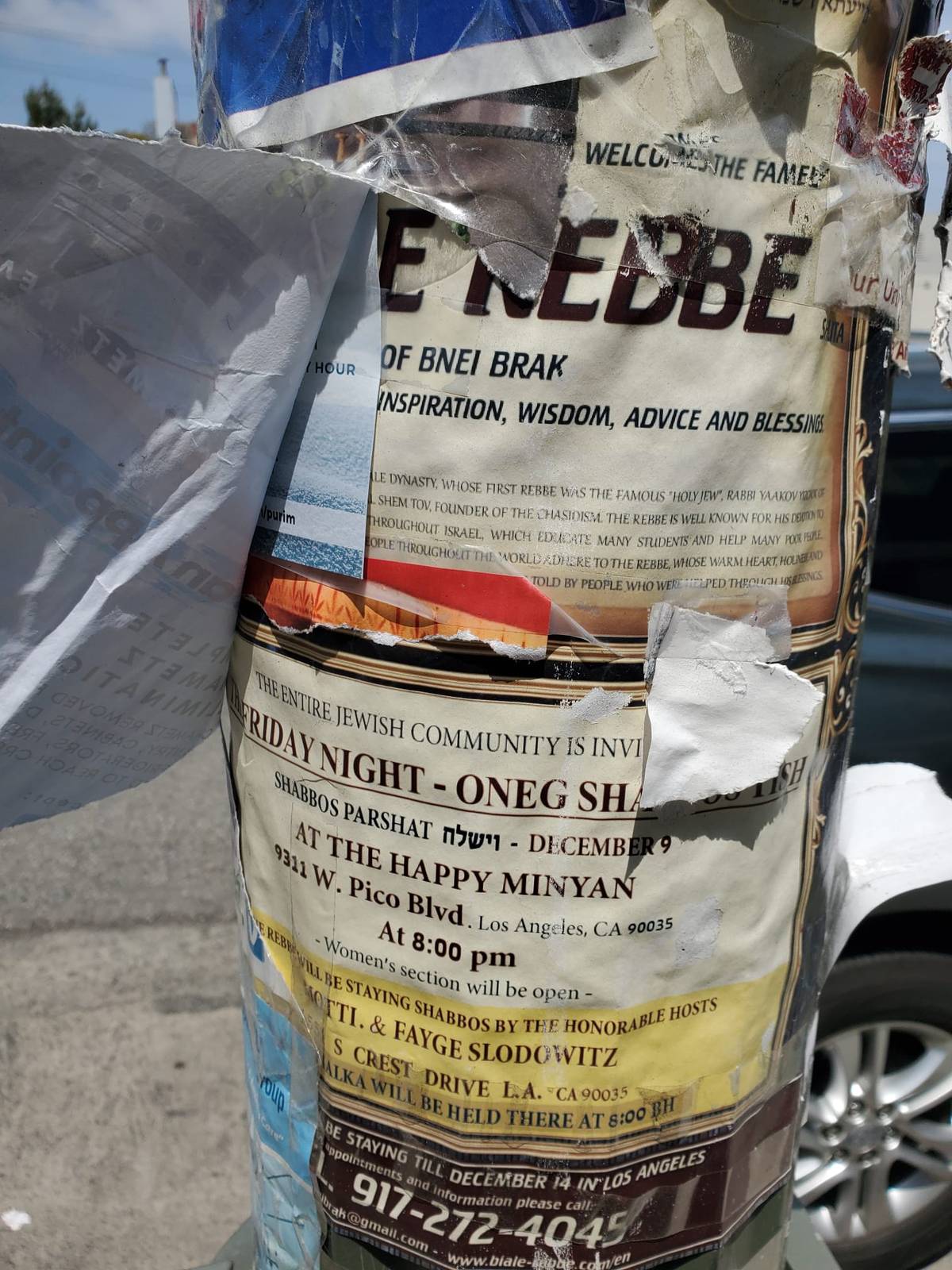

Some of the most evergreen flyers taped up involve announcements of visits by the Biale Rebbe, a descendant of the Biale dynasty “known for his inspiration, wisdom, advice, and blessing,” per the flyer. I called a friend who is close to the Biale Rebbe to ask him about these, but it turned out the flyers were for a different Biale Rebbe, the brother of the one my friend knows (the one he knows is from Jerusalem; the advertised one is from Bnei Brak). Adherents of each will caution to accept no imitations, to make sure, if you do go, to go to the correct one; while the dynasty originated in Biała Rawska, Poland, it now has branches worldwide.

Sometimes, it can feel like LA is expressing its essential unease, the preoccupations it swears by and then it immediately disavows, through its signs and billboards. In the classic 1991 Steve Martin movie LA Story, his character gets advice from whimsical traffic signs by the side of the road. Is that what people are hoping for when they put billboards and flyers up? To issue advice, rather than receive it?

Erez Safar recently put up flyers around the neighborhood featuring the phrase “God is revealed and concealed in love.” This phrase puzzled me when I first saw it. If I’d wanted to take advice from it, like Steve Martin in LA Story, I’m not sure I would have been able to. What did Erez hope to achieve with his sign? I asked him over Messenger. So much of what we see is advertising, he wrote back. He was inspired by Shepard Fairey to take his message to the streets. As for the signs’ meaning, he wrote: “Concealed and Revealed within love / Concealed when love is lacking when we act from the opposite of love ... meaning we judge unfavorably and act from darkness and hate and revealed within love when we act from it when love is revealed within us brought out within us and each other.”

Wanting to be upfront, I told him it gave me a headache. He said he was happy it had provoked any response, but our exchange grew increasingly testy, for which I take full responsibility. The sentiment had its roots, he said, in complicated Breslover philosophy. I could buy his book for more details. But I should know that a girl in Williamsburg was touched by it and featured it on her Instagram. Deepak Chopra reached out to him on his mother’s second yahrzeit. Maybe shorter was better. I did not like being condescended to when he told me it was too profound to explain to someone like me, or that too much explaining would ruin it. “I think people are used to seeing signs that are advertising something and rarely a thought about love or light,” he said, and he wanted to inspire people, not add to the negativity in the world. I could still buy his book for further clarification. When he insisted that if I write about it, I do it in a spirit of positivity, this struck me as a little dictatorial for something quite literally posted in the public square. But it made more sense when he mentioned that it was a tribute to his late mother. I have been in grief, too, and I too have looked for signs. I could understand why someone would want to put their own code out there, to pass the headache on.

If you ask me which flyers I prefer, I’d tell you the less cryptic ones. A current one is for An Evening of Miracles, featuring the CEO of American Dream and a full sushi bar. Why would you stay in and watch Netflix with that as an option?

As it happened, I did go to see the Biale Rebbe a few years ago (not the advertised one, the other one). Not because of the sign but because he was being hosted by my friends, who importuned me to visit. The vibe was medieval court-cum-LA-balcony party, but the Biale Rebbe is no pothead. He vapes tobacco, incessantly and with determination. On the one hand, I was concerned for his health, but on the other I thought it was pretty impressive to make an appearance with one’s own personal smoke machine. He puffed away as we chatted, writing notes in Hebrew on a piece of paper while the smoke curled around his beard and the gray wisps became indistinguishable from his facial hair.

After some pleasant back and forth through a translator (he spoke modern Hebrew, not Yiddish), he told me that “nothing is missing.” Quite a lot was missing from my life at the time, but I found the idea reassuring. I went back out into the California night feeling some residual embarrassment at having been there in the first place, but also a bit philosophical about the idea of lack, what it means to feel satisfied. Have you ever found something pleasant but also regretted doing it? It was like that. I found him refreshingly normal, chatty. I also felt quite good about my decision to not make a donation. But that’s not the kind of testimonial you could put on a flyer.

Street posts are where we put our grief and our attempts to connect. Those attempts will reach some, irk others—should anyone note them at all. These flyers and billboards are, of course, about selling things. What unites them is their promise of inspiration and rejuvenation, vaginal or otherwise. That promise will be alluring to some. For others, their innermost parts will feel just fine as they are, barely touched by the California sunshine.

When I mentioned to my fiancée, Rachel, that I was writing about the signs on lampposts in our neighborhood, she said, What? Like a normal person, she largely tunes them out. I am less likely to take in what they are trying to tell me, since we got engaged. I see that it takes a certain intelligence to read the signs, but a greater one sometimes to ignore them, that happiness is a great cure for trying to make sense of the signs around you.

Emil Stern is an Australian screenwriter living in Los Angeles. He is working on a book about his family, Displaced Persons.