Pastries, nuts, and beverage bottles crowded a table. Towels draped a wall mirror in a traditional display of mourning. Visitors sat around a widow and her two small daughters, speaking softly. On the balcony, the deceased man’s sister chatted with friends. Their father, gray stubble of mourning filling in, stood holding a cup of soda.

Last Wednesday, the shiva for Saar Margolis resembled what might be expected anywhere in the Jewish world but for its unconventional setting: a suite at the Leonardo Plaza Hotel, a suite offering stunning views of the Dead Sea seven floors below, a 90-minute drive east of his home.

Margolis, 37, was killed on October 7 in a battle with Hamas terrorists who infiltrated his community, Kibbutz Kissufim, just east of the Gaza Strip. The 1,400 Israelis whom Hamas murdered and the 200 it kidnapped from communities throughout the area, known as the Gaza Envelope, included nine dead Kissufim members and four kidnapping victims held in Gaza. Hamas also murdered eight Thai field workers living at Kissufim.

The late Saar Margolis (back left), his sisters Stav (standing next to Saar) and Marcelle (back right), and their father, Selwyn, were caught up in Hamas’ October 7 attacksCourtesy Marcelle Margolis

Kissufim survivors were evacuated late that night to the hotel, near the Dead Sea’s southern end, bereft of nearly everything but the clothes on their backs.

They had no opportunity to collect photo albums, loose snapshots, yearbooks, mementos, collectibles—items that loved ones sitting shiva in normal times would examine to take the measure of the deceased person, to jar memories, to recall a life led, to share with those coming to comfort.

The impersonal venue “doesn’t matter to me,” said Saar’s father, Selwyn, 86. He appreciates the personal touches being extended, he said. At daily services in the synagogue downstairs, men sitting alongside alert him each time to recite Kaddish, the mourners’ prayer.

“The last time I said Kaddish was for my mother and father, 50 years ago,” he said.

Chatter in the hotel suite split into two topics. One was Saar Margolis the man, the husband, the father, the hero. The other was the catastrophe that struck the Gaza-area Jewish communities 11 days earlier, with people relating tales of sorrow and shock and survival—stories similar to those told in countless other rooms in the hotel, and in other Dead Sea hotels, and in hotels 140 miles south in Eilat, all housing evacuees from the shattered kibbutzim and towns.

“Maybe next week, when I’ve had some time, I’ll walk to the beach,” Saar’s sister Marcelle said on the balcony. “It’s a beautiful spot.”

Within days, a mini-society, a community—however temporary—sprouted at the Leonardo Plaza to assist those from Kissufim and the towns of Sderot, Ashkelon, and Ofakim, home to the hotel’s other evacuees. Government agencies, nonprofit organizations, companies, and full-hearted Israelis are addressing the guests’ needs. They’re trying.

Bulletin boards carry notices about veterinary care; a shuttle-bus schedule to and from a shopping district in Arad, 20 miles away; a concert that afternoon on the lawn by the pool; and a medical clinic, dental care, an ATM, and postal services, all on-site or at another area hotel. Social workers see traumatized patients. Specialists from the optometry factory at Kibbutz Shamir, a long haul away in Israel’s Galilee panhandle, come to fit people for eyeglasses. Singer David Broza and the band Hadag Nahash performed.

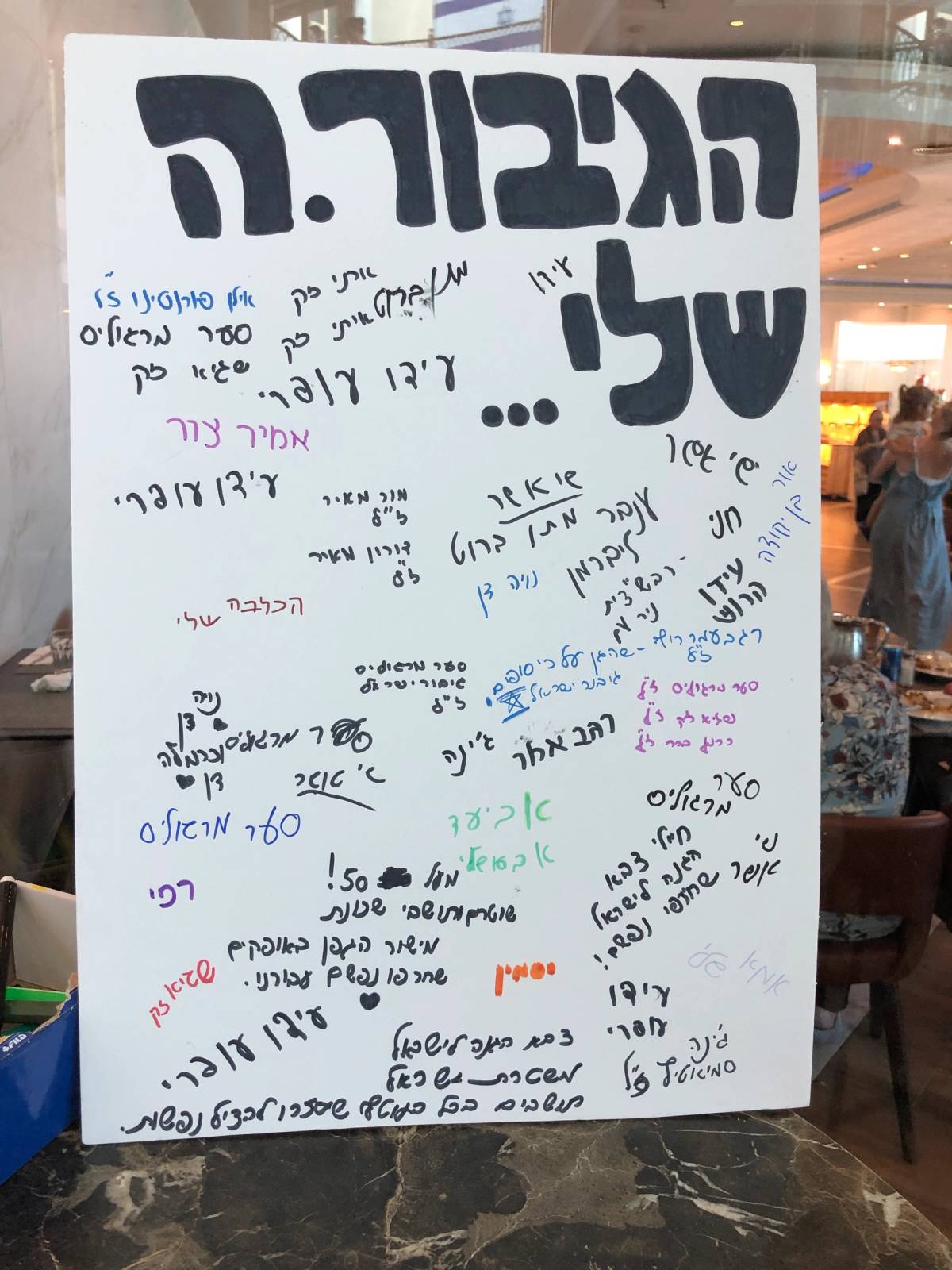

A poster in the hotel foyer for families to add names of loved ones killed in the attacks. The heading reads ‘My Hero/Heroine.’Courtesy the author

Across from the dining room, a ballroom has become a flea market of used haberdashery. Boxes and boxes sit upon tables and tables, all well-marked and well-stocked: underwear, socks, T-shirts, blouses, jeans, and slacks; boys’ and girls’, men’s and women’s; small, medium, large, extra-large; in a vast array of colors and designs. On the floor: shoes, sneakers, and flip-flops in numerous sizes.

In a corner are piled the only items whose availability is supervised: diapers and baby formula. In another corner, behind partitions, physical healing is offered: massages, acupuncture, Chinese medicine, and the like.

In a landing above, evacuees have their pick of canine accouterments: leashes, muzzles, and toys.

The products and services all are free of charge.

“We have helped them to heal, to release trauma through the body’s systems,” said Idan Yahalomi, an alternative-medicine practitioner from a Tel Aviv-area moshav who, the day after the massacre, headed to the Dead Sea sites to open the holistic clinic. Eight practitioners, all certified and all volunteers, each see two clients an hour from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m., six days a week.

“We try to give them a safe space to chill, to not think of anything,” she said. “They deserve it. They’ve been through a lot.”

In the foyer between the dining room and ballroom, a poster board and a box of colored markers sit upon a table. “My Hero/Heroine” reads the black heading in Hebrew. Under it, people had written, all in Hebrew, the names of their dead loved ones. Some are:

Ilan Forentino

Sagi Zak

Eti Zak

Rafi

Doron Meir, of blessed memory

Mor Meir, of blessed memory

my dog

Amir Tzur

Noya Dan

Carmela Dan

the more than 50 police officers and residents of the Mishor HaGefen neighborhood of Ofakim who gave their lives for us

Gina

the IDF officers who sacrificed their lives!

Shai Asher [twice]

Saar Margolis [three times]

Across the foyer, approximately 35 yahrzeit candles burned. A printed sign above them read:

The Jewish people will remember its sons, daughters, and all of those families’ generations, the faithful and the brave, who were murdered in Israel by murderers from terrorism organizations.

They will be inscribed in the hearts of Israel forever.

Beside another tray of burning candles, a woman from a religious community reached into a bowl of dough and made the blessing for separating challah. A dozen women gathered around her responded, “Amen.”

“The idea is that doing good deeds, especially the mitzvah of separating challah,” the leader explained later, “speeds the departed soul’s entry to heaven.”

Saar Margolis grew up on Kissufim, brought his bride there from her native Ashkelon, raised their two daughters there, worked there for 15 years as its security head before starting a Defense Ministry job eight months ago, died there defending his home, and is buried there.

His burial was complicated.

Yasmin Margolis wanted her husband interred in the cemetery of Kissufim, a 300-resident kibbutz that raises potatoes, avocados, carrots, radishes, and chickens and runs a dairy operation. But with the security situation remaining tenuous, his body remained in cold storage.

On Sunday, Oct. 15, eight days after his death, Saar Margolis was returned to Kissufim. Because of the prevailing danger, only four loved ones were permitted to see him off: Yasmin; Selwyn; Saar’s mother; and Marcelle’s son, in uniform and armed, having been called up to the reserves. The burial was hasty. A proper funeral was conducted at Beer Sheva’s military cemetery earlier that afternoon.

Tables of donated items in the hotel ballroom Courtesy the author

The family’s fears on October 7 ranged wide and its anxiety remains high, with five relatives still in captivity in Gaza. Three Margolis households reside on Kissufim and one nearby, at great risk during the invasion.

Marcelle Margolis had alerted everyone that she was fine, staying with a friend in Beer Sheva since Oct. 6 to celebrate the Simchat Torah holiday. No one knew how Selwyn was, or Saar and his family, or Saar’s sister Stav Cunio and her family on Kibbutz Nir Oz, just south of Kissufim.

Selwyn awoke that morning to a red-alert siren. He took cover in his home’s fortified room. He stayed there during most of the siege, but was fairly unreachable by phone call or text due to poor cellular reception in the room. He went to the kitchen at about noon and saw his neighbor’s parked car ablaze. He texted later that afternoon to report his front door being broken down—by terrorists or by rescuers, he didn’t say. Turned out, the terrorists never came for him. Rescuers broke the door to try to reach him, but he’d remained silent.

Saar, Yasmin, and the girls huddled in their fortified room, until Saar left with his weapon, rendezvoused with three fellow security men, and mobilized to defend the kibbutz.

On Nir Oz, the terrorists burst into the Cunios’ home. Stav, her husband Eitan, and their two little girls were in their fortified room. The Hamas men shot the door. They jerked its handle, but Eitan pulled it for dear life. The terrorists then burned their home, as they did others’, in a bid to force out the residents. The Cunios stayed put. Eventually, they were rescued, hospitalized with burns and smoke inhalation, and released.

Eitan’s twin brother and four other members of the brother’s family were kidnapped from Nir Oz and taken to Gaza.

At 1:20 a.m. on Monday, Oct. 9, about 43 hours after Hamas’ invasion, a Kissufim resident knocked on Marcelle Margolis’ hotel-room door, needing to speak with Selwyn.

“I knew straightaway what it was,” she said. She’d “worried about everybody,” she said, but “I didn’t think of worrying about Saar” because of his expertise in security: “I thought of him as Rambo.”

She accompanied the other kibbutznik to her dad’s room. At 1:30, they knocked.

He’d texted Shabbat Shalom greetings to Saar the night before. Father and son spoke briefly.

“I said, ‘I’ll see you tomorrow afternoon on Shabbat’—and that’s it,” Selwyn said.

“I don’t know how I’ll get along without him. He was very special,” Selwyn related in the hotel’s dining room, its lunch crowd of refugees from southern Israel having nearly emptied. He spoke clearly, calmly.

Selwyn and Saar got together every day. Saar brought Selwyn’s granddaughters over several times a week. Asked what he and Saar enjoyed doing together while alone, Selwyn laughed.

“Drinking beer and whiskey,” he answered. “We’d talk about life, plans, and politics.”

He continued: “If every father had a son like Saar, he would be proud. He was a very good son. If I needed anything, he would always be there for me. I would walk to him, and he would walk to me. I would cook for them.”

He turned the screen of his cellular phone to display jahnoun and sambusak, some of the Middle Eastern baked goods he enjoyed preparing for them.

Saar came to be born and to die on Kissufim because Selwyn liked the place from Marcelle’s having lived there while serving in the IDF after immigrating to Israel. (Selwyn and the first four of his six children are from South Africa.) In the mid-1980s, a friend got Selwyn a job at a Kissufim factory. The kibbutz is where he met his second wife, a Kissufim resident. He raised their family there. Saar as a boy liked judo and soccer. In the military, he trained in a canine unit. At his death, Saar was a semester short of earning a master’s degree in security.

“Security was his life,” Selwyn said. “I believe that this is the way he wanted to go.”

After his divorce from the mother of Saar and Stav, Selwyn remained on Kissufim. At the hotel, he was asked if he’ll return there to live, given what’s happened.

“Of course, I’ll go back there. Of course,” he said.

Their father-son routine is gone, “but I have his grave,” Selwyn said of Saar. “I can see his grave every day. I’m very happy I know where he is. He’s on the kibbutz, and I can see him every day. I can relive the memories I had with him.”