Soldier Boy

The long afterlife of Pvt. Albert Birnbaum

When my Grandma Sadie was still alive it was impossible to speak of the death of her youngest child, Albert. The facts, as recorded by the U.S. Army, are that Albert Birnbaum was a private in the 9th Army, 90th Infantry Division, 357th Infantry Regiment, and he died 20 days after D-Day, on Monday, June 26, 1944, sometime between midnight and dawn, on the Cotentin Peninsula, near the Douve River, about 15 miles south of Cherbourg.

The campaign to take Cherbourg’s deep-water port had been slow and bloody, the Germans having the advantages of four years of occupation and Normandy’s hedgerows: banks of earth surmounted by thick tangles of hedge and vine that demarked fields and meadows and kept farm animals from wandering. Invisible within a hedgerow, a rifleman could see an advancing enemy from the moment he pushed through the next nearest hedgerow and began to cross over the open field. Machine guns at the hedgerow corners could together sweep the field. Enfilade is what it’s called, a beautiful war word that means a horror. Albert’s regiment had a hard go of it. On June 13 the unit of some 2,000 had been in combat for four days and had already suffered 703 casualties, including 130 dead. Daily progress was often measured by hundreds of yards, and there were days when no ground was gained and days of retreat. On June 14 the 90th Division’s commander and two regimental commanders were replaced.

On June 25, with American forces on the verge of entering Cherbourg, the 357th was holding a defensive line with the aim of keeping enemy troops from moving up the peninsula to reinforce the city. In the early hours of June 26, according to the regiment’s After Action Report: “An enemy patrol struck in force in the area of the OPLR [Outpost Line of Resistance] of the 357th and made slight penetration. Hand grenades were used extensively between our units and the enemy patrols. The enemy was destroyed or taken prisoner. The 357th’s lines were restored. 40 prisoners including one Regimental Commander and two Lieutenants were taken. 357th suffered 13 casualties.” No other casualties for June 26 are reported.

Albert was tall, skinny, spirited, and had just turned 20.

Grandma Sadie declined belief in Albert’s death. The War Department was mistaken. Albert, she said, had suffered a head injury that caused him to forget who he was. But one day he’d remember and come home, walking up the stairs to the second-floor apartment at the outer edge of Brooklyn, where a gilt-framed portrait of him in uniform stood on a side table in the living room. He probably wouldn’t be alone, she said, but with the French girl he’d married and their children. And then everyone would fly to Israel to celebrate. (In anticipation of the cost of the journey, Grandma Sadie annually bought chances in the Irish Sweepstakes from a door-to-door bookie.)

Growing up, I knew, as everyone seemed to know, that Uncle Albert was dead. In fact, I had a younger brother named Eliyahu, which was Albert’s Hebrew birth name, and our kind of Jews never named children for any living person; only the dead. Still, I never heard anyone in my family, under any circumstances, dispute Sadie’s story—not her husband, not her two daughters, not my mother. And not my father, who on the night his brother died was perhaps 20 miles distant, at the bottom of the Cotentin Peninsula with the VII Corps, then attached to the First Army. One day, probably in mid-July 1944, before the VII Corps, on July 24, participated in the breakout from Normandy, my father requisitioned a jeep and went to say Kaddish at Albert’s grave. My father had a driver during the war, a private from Oklahoma, and it was he who probably took the photograph. My father crouches beside a 6-foot-long rectangle of heaped raw soil. At its foot is a white wooden Star of David secured to a bit of timber impaled in the ground. Similar heaps, marked by white wooden crosses and one other six-pointed star, are arrayed behind him and as far as the photo image extends. My father, in a dark uniform and a helmet, is bent over an open book, no doubt a siddur. His face is covered with a black cloth from below his eyes to below his chin—perhaps a matter of hygiene, perhaps to mitigate the smell of the unburied dead.

I heard Sadie’s Albert story many times when I was a boy, often when my brother Akiva and I visited her on languid Sabbath afternoons and sat at her white-and-black metal kitchen table and ate bowls of My-T-Fine chocolate pudding and whipped cream. We were there because my Grandpa Leo was frequently absent on weekends, and we were assigned to keep Sadie company. Obliged to make conversation, we said a few things about school or about our younger siblings. Sadie filled in with her own stories. She told us about a brother and sister who were playing inside an abandoned ice box on the sidewalk down the street and suffocated after the door closed on them. And about the time, back in Galicia, when she was sent to open the door for Elijah the Prophet at the Seder, and a goat walked in, terrifying her. Or of how she was always able to elude Satan by spitting three times on the ground when she knew he was near and then hurrying off while der Sutin, who could not help himself, bent like a dog to smell the saliva. And there was the story of her damaged right eye, teary, half-closed. It seems that Albert ran away when he was a boy, and she wandered the neighborhood all night looking for him, and some men came to her in the morning to say they had found him asleep on a bench in the Sephardi synagogue. But it was too late; she had worn her eye out. And she talked about Albert’s imminent return. Joining the two Albert stories was, of course, beyond us, as was sorting out the thematic thread of imperiled children.

Sadie never called him Albert but Ell-ee, a diminutive for Eliyahu. That’s what we learned to call him, too: Uncle Ellee.

Grandma Sadie declined belief in Albert’s death.

I was a young man when my mother first spoke to me about Albert. She was several years divorced from my father and no longer trapped in the silences he’d imposed on her. She said she came to know Albert after she and my father were engaged. She was at Hunter College then, studying to be a teacher, and my father asked if she would help his brother with schoolwork. So she would sit with Albert at that kitchen table. He was the kind of boy, she said, who had no patience for books, for sitting still. Still, he tried to do as she asked, to please her, and she’d loved him for it. And I’ve no doubt he came to love her. She was a tall, beautiful, sad young woman.

She told me that Albert tried to enlist soon after Pearl Harbor, when he was still in high school. But the Army discovered he was not yet 18 and turned him away. So he left high school and Brooklyn for Delaware, to work in a mill that manufactured uniforms and parachutes. Grandma Sadie was troubled. She wondered how Albert could follow Jewish religious law in Delaware. Was there kosher food? Was there a shul? And then one day Sadie discovered that her son had left behind the tefillin—phylacteries—that every pious Jewish man wraps around his arm and places on his forehead while saying morning prayers.

Albert returned to Brooklyn soon after he turned 18.

My mother told me that he was shot in the back by a sniper while swimming in a river. She knew because he had used to come to her in dreams, standing bare-chested in the water.

Albert Birnbaum was born on Thursday, May 15, 1924, in Brooklyn. His parents were Sadie and Leo; his sisters were Toby and Selma; and his brother, my father, was called Meyer or Mike or Moe. Albert registered for the draft on June 30, 1942. His draft card named his mother as next of kin. The card said he was a “student,” 6 feet and 2 inches tall, weighing 170 lbs., of “light” complexion, with brown hair, with gray eyes. He was assigned to a division based in Texas and Oklahoma (its nickname was “Tough Ombres”) that trained in California, Louisiana, and Arizona before arriving at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on Dec. 31, 1942. I assume that the portrait in the gilt frame was taken while Albert was on leave from Dix, as was a portrait of Albert and my father in dress uniform. Though there’s no one else in the frame, they’re standing close to each other, one behind the other, their right shoulders slightly turned away from the camera. They are looking straight into the lens. My father, in front, is mustachioed, his service cap at a tilt, roguishly handsome. My uncle, behind, is a beautiful, pale boy. Both are solemn. A photo of their dog tags and chains, tumbled together, is ghosted into the print beside them, two silver tags for each of them, one to be removed from the body for reporting purposes, and one to remain with the body for identification purposes.

Albert sailed for England on March 23, 1943, on the HMS Dominion Monarch, a converted British luxury liner. He trained for the invasion in the West Midlands. My father was already posted close by, and I imagine they saw each other often. Before my father left the States, Grandma Sadie had extracted from him the fearful promise that he (a lieutenant) would take care of his younger brother (a private).

Albert landed on Utah Beach on June 8. Though the beach had been under American control for two days, it still took intermittent artillery fire. He was in combat two days later and every minute of his life afterward. He is buried just a few miles north of where he came ashore, in the American cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, above Omaha Beach, where the low arched memorial stones are set in long rows with their backs to Europe, facing home. He lies in Plot I, Row 14, Grave 28. I have been there, as have three of my brothers. I said Kaddish, as did they. A French friend who drove me there read Psalm 23 in English: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.” He read to the end: “And I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” Sebastien took a few pictures. We had brought some pebbles, and placed them on the white star. “Pourquoi Ben pleure?” one of Sebastien’s young daughters asked. He whispered something to her. I myself could not have answered her question, though I remember thinking how much easier my father’s life (and my life and my mother’s life and the lives of my brothers and sister) would have been if only my father had brought his little brother home, as he’d promised.

After this we descended a set of zig-zagging concrete stairs that took us to the beach. We passed divots in the hill, the remains of what had been German bunkers. It was a beautiful July day. The sea was blue-green. My friend’s daughters played in a tidal pool. Their mother, Juliette, told them not to get their clothes wet, but it was too late.

How Sadie came to think that her son had not lost his life—as the War Department’s telegram would have asserted—but only his memory, is a mystery to me. Random Harvest, a December 1942 release from MGM, recounts the adventures of a British soldier (Ronald Colman) in WWI who lost his memory after being rendered unconscious in battle and, when the war ended, married a French woman (Greer Garson) and eventually (during a lightning storm) came to recall his life prior to the war, and returned home to his joyous family. Could Grandma Sadie have seen the movie or read the novel on which it was based? Highly unlikely. I can remember no books in her apartment except for a siddur or two. Nor was she a woman who went to the movies or who would have spent more than a few minutes in a theater listening to Colman’s velvety British tones or Garson’s West End locutions before hurrying up the aisle and then home, where there were quilts airing on the porch rail that needed to be taken in before it rained. Moreover, American English—which Sadie did not hear or speak until she was past 20—was sufficient challenge for her, a woman who sometimes spelled her name “Sadey.”

And then there’s the puzzle of the news story that I came upon some years ago when I was index-searching the Brooklyn Eagle for references of my grandfather Leo, who’d been a prizefighter in the first decades of the 20th century and later a prominent boxing judge and referee at Madison Square Garden. The story was below the fold on the front page of the Dec. 22, 1944, edition under the striking headline “Mystery GI Fans Hope Hero Yank May Live.” The “Hero Yank” is Albert. The “fans” are Grandma Sadie and Aunt Selma. And the “Mystery GI” is a soldier who was said to have stopped a week earlier at a “corner grocery store” near Sadie’s apartment, asking for an address for Mrs. Birnbaum, for whom he had a message from his Army pal, her wounded son. The store clerk didn’t know Mrs. Birnbaum, the newspaper said, and the soldier left. And then—the Eagle did not say how—the story of the Mystery GI’s quest landed in Mayor LaGuardia’s office, and LaGuardia made a personal plea on his weekly radio show for the soldier to come forward and visit Mrs. Birnbaum at 21 Malta Street and let her know that her son lived. The newspaper also noted that Albert was “on a special hazardous mission” when he was said to have been killed, and that my father had received a letter from Albert on July 18, which was proof that Albert had survived the June 26 firefight, because a letter from the 157th Regiment to the VII Corps sent prior to June 26 would have arrived long before July 18, “according to the War Department.” The fevered and clumsy story was published with a photograph of Sadie and Selma alongside that gilt-framed photo of Albert. The women are posed like bookends, Sadie turned to the picture that seems to float between them, and the beautiful, dark-haired Selma bent over “his most recent V-mail letter.” They appear so nakedly stricken that a decent person should want to turn away.

How did the Eagle story come to be? Who concocted it and fed it to the PR guys in the mayor’s office? (“Mr. Mayor, we got something good for your broadcast. Yeah, the Eagle’s gonna run it too.”) Was it my grandfather? Doubtful. He didn’t have the imagination and, in any case, cared little for his wife, to whom he’d been unfaithful (in every way) and whom he often referred to as “Tsuris,” a play on “Suruh,” the Yiddish pronunciation of her name, and meaning “troubles.” Was it one of the sisters, who were young women by then? Was it my father? Did he send instructions to his sisters from Europe? And was the aim to provide a disconsolate woman with some temporary hope; and did that hope then explode into a lifelong obsession? Or was the fantasy already in play, and the intent was to support a mother’s desperate invention? And while everyone—my father, mother, aunts—certainly read the Eagle story when it appeared, none of them ever spoke of it in my presence or in the presence of any of my four brothers and sister. Why? Had they been involved? Did the story shame them? And why didn’t Sadie, a cunning and practiced fantasist, ever say to Akiva and me on those Sabbath afternoons: “And there was a big newspaper story with a picture of your Uncle Ellee. And the mayor said he was only wounded. So that’s how we know.” But the “Mystery GI” never stepped forward; nor did the Eagle ever return to the story. Nor, I’m guessing, did LaGuardia call or write to ask how it all worked out.

The mystic and healer known as the Baal Shem Tov (1698-1760) spent his life in western Ukraine and left no books, no written record. What he is said to have said and done, however, was transmitted orally, over generations, and eventually engendered many books and the pietistic revivalist movement known as Hasidism. He is said to have said: “Exile comes from forgetting. Memory is the source of redemption.”

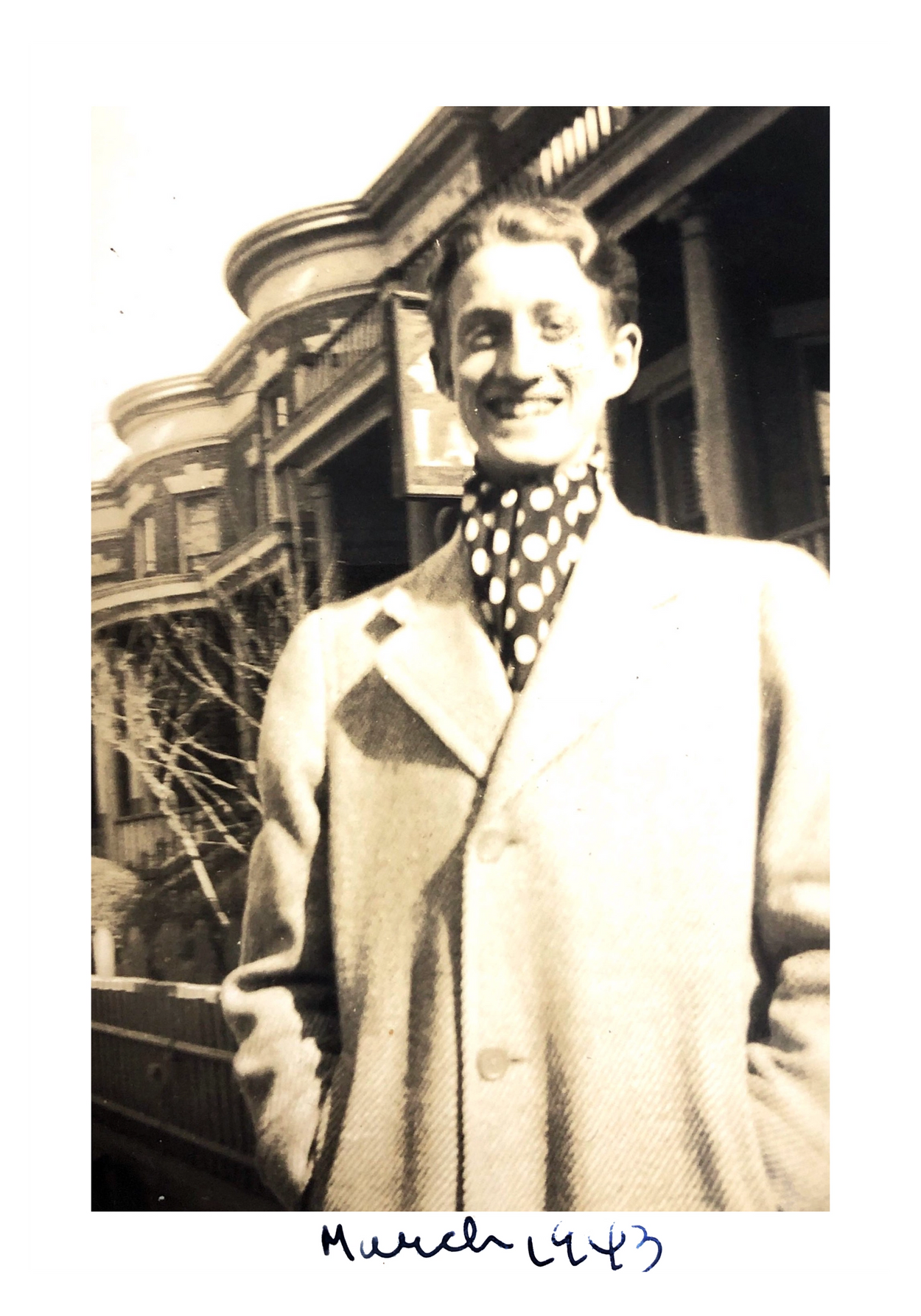

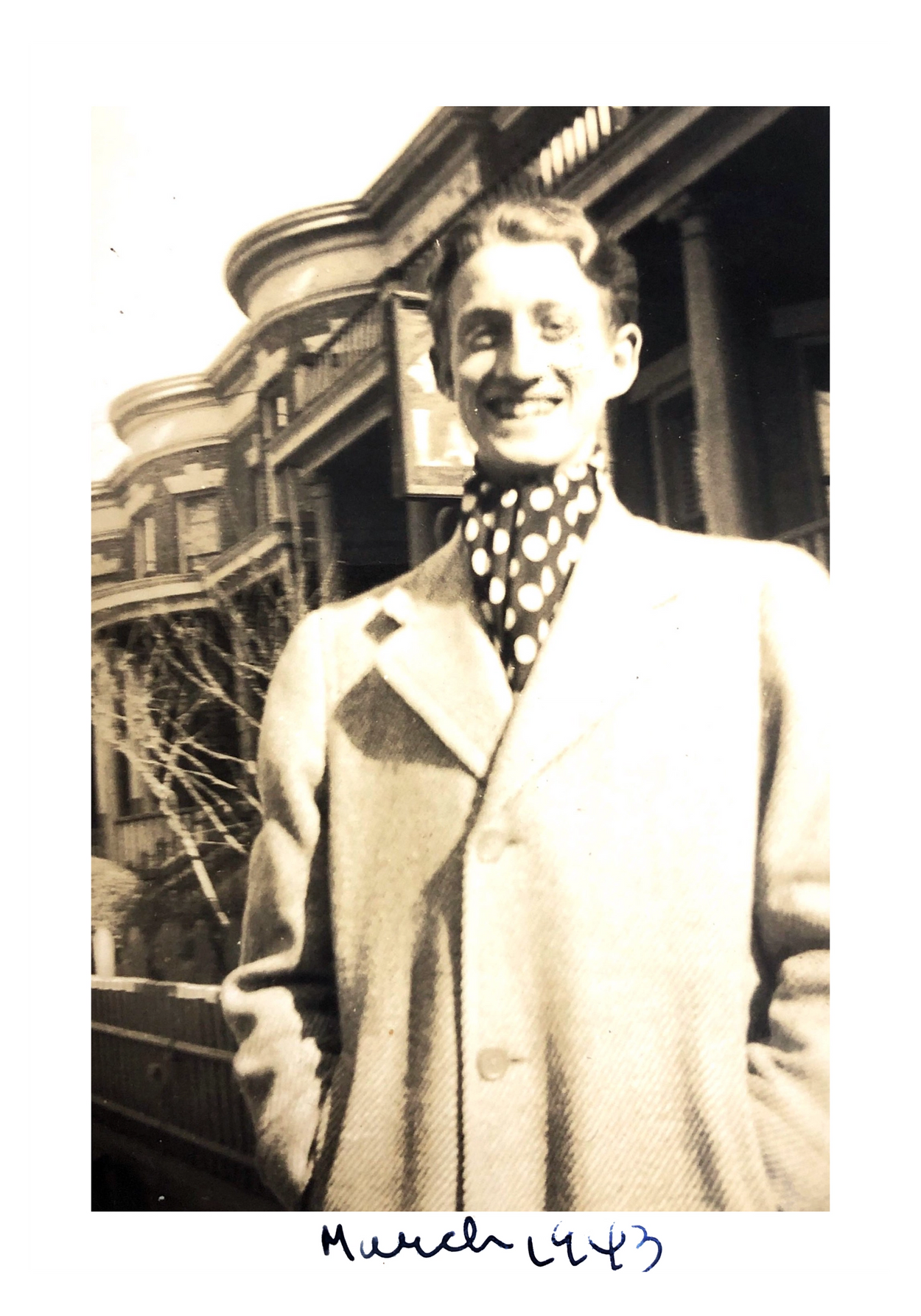

There are fewer than 10 photographs of Albert that I’ve been able to find. One shows him as a young man, standing in front of the Brooklyn house, laughing, a polka-dotted silk scarf draped around his neck. Another has him in an outdoor boxing ring on what appears to be an Army base, wearing laced leather boots and a leather helmet, his head down, his face between his carefully positioned gloves. And one, another snapshot, shows him in the living room on Malta Street, likely in early 1943, when everyone was together for the last time. It was a sad little room, in the middle of the apartment, dimly lit by windows to an airshaft. He’s sitting on the sofa, in uniform, bareheaded, smiling up at the standing photographer, probably one of his older sisters. His left arm is at his side, but his right arm is folded across his body, long fingers extending toward the camera, as though waving to us or warning us away.

Ben Birnbaum is a writer and editor in Brookline, Massachusetts.