Songs From the Ghetto

Rokhl’s Golden City: Preserving musical testimonials from the Holocaust

January 27 is the United Nations-designated International Holocaust Remembrance Day, honoring the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau by the Red Army. In the past, I’ve urged readers to observe it by seeing the superb Warsaw Ghetto documentary, Who Will Write Our History. This year, I’m assigning something a little bit out of left field: Orson Welles’ 1946 small town noir, The Stranger.

In The Stranger, war crimes investigator Wilson (Edward G. Robinson) is in pursuit of Franz Kindler (Welles). Kindler is a fugitive Nazi mastermind, one who managed to remain in the shadows during the war. At the end of the war, he erases all traces of himself in Europe, then escapes to bucolic Connecticut, where he is about to marry into the town’s blue blood elite.

Among the many masterful images in the film, foremost in my mind occurs toward the beginning. Kindler has been tracked down by his former assistant, Meineke, who has come to ask Kindler to repent for his crimes. On his way to meet Meineke, Kindler is detained by a group of the town’s boarding school students. In matching sweat suits, the American boys are cartoonishly fresh-faced and buoyant, contrasting starkly with the skittish Kindler.

The boys are off on a “paper chase,” in which one of them runs ahead into the woods, strewing strips of paper, which the others collect. Kindler, too, is off to the woods—in his case, to murder Meineke. Unfortunately for Kindler, the leader of the paper chase inadvertently strews a path right to Meineke’s dead body. Kindler scrambles about in the dirt, quickly redirecting the paper trail and covering his own tracks. His relief is palpable as the rest of the boys run past. They are oblivious to what has just happened, and what still lurks in the woods.

The subtext here is not subtle: It’s much easier to not think about the monstrous things that lie just out of sight, to just run around them. And we are foolish to think that just because the war is over, the Nazi menace has been defeated once and for all. Nor should we be led astray simply because the accused has attempted to cover his own tracks.

No, fascists had to be rooted out, wherever they were. But first, the world had to be educated on (and convinced of) the full extent of Nazi crimes.

In the spring of 1945, Welles attended a conference where he viewed newsreel footage of the liberated concentration camps. Convinced of the threat of “renascent Fascism,” he went on to use similar footage of concentration camps in The Stranger, where the Nazi hunter Wilson has to convince Kindler’s fiancée that she is protecting a monster. It was the first commercial movie to use such films. With just a few seconds of film in The Stranger, Welles demonstrates the power of archival images to speak the unspeakable.

Music, too, has come to be an important part of Holocaust narrative and memory. To take just one example, in 1965, Folkways Records released Songs of the Ghetto, featuring Cantor Abraham Brun. Cantor Brun was a survivor of the Lodz Ghetto and the songs on the album connected to his wartime experience. Some he sang in the Kultur-Haus on Krawieca Street, as the liner notes tell us, some in the “Intellectuals Kitchen” on Zgierska Street, in a prewar cinema: “These songs, some of which call for courage, others merely voicing despair and pain, are an important and unique part of the Literature of the Holocaust. They bring you right into the heart and soul of the sufferers.” And with mass production and easy availability of records, Brun was able to not just record these songs, but also provide annotations. The record is accompanied by Yiddish and English translations, as well as wonderful explanatory liner notes.

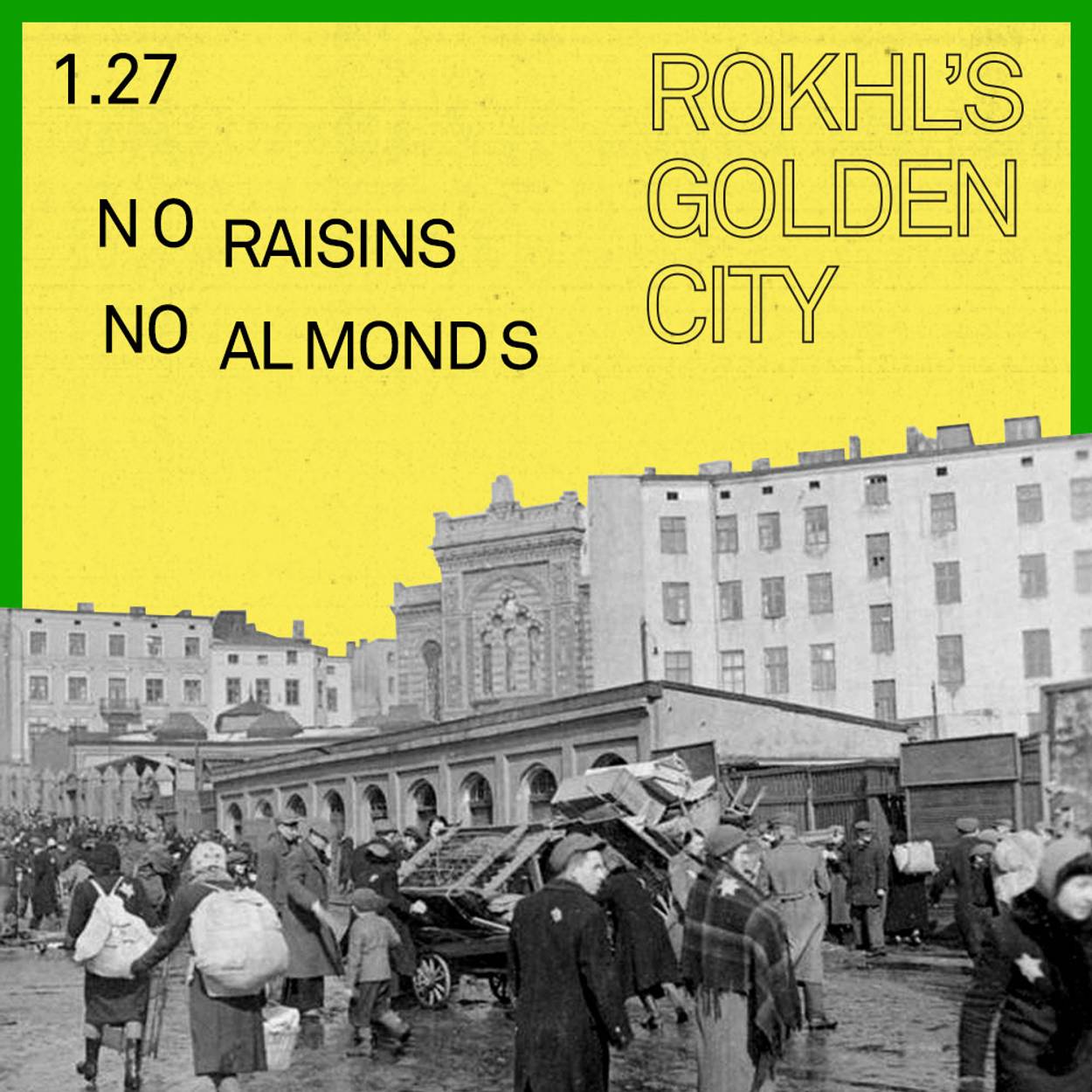

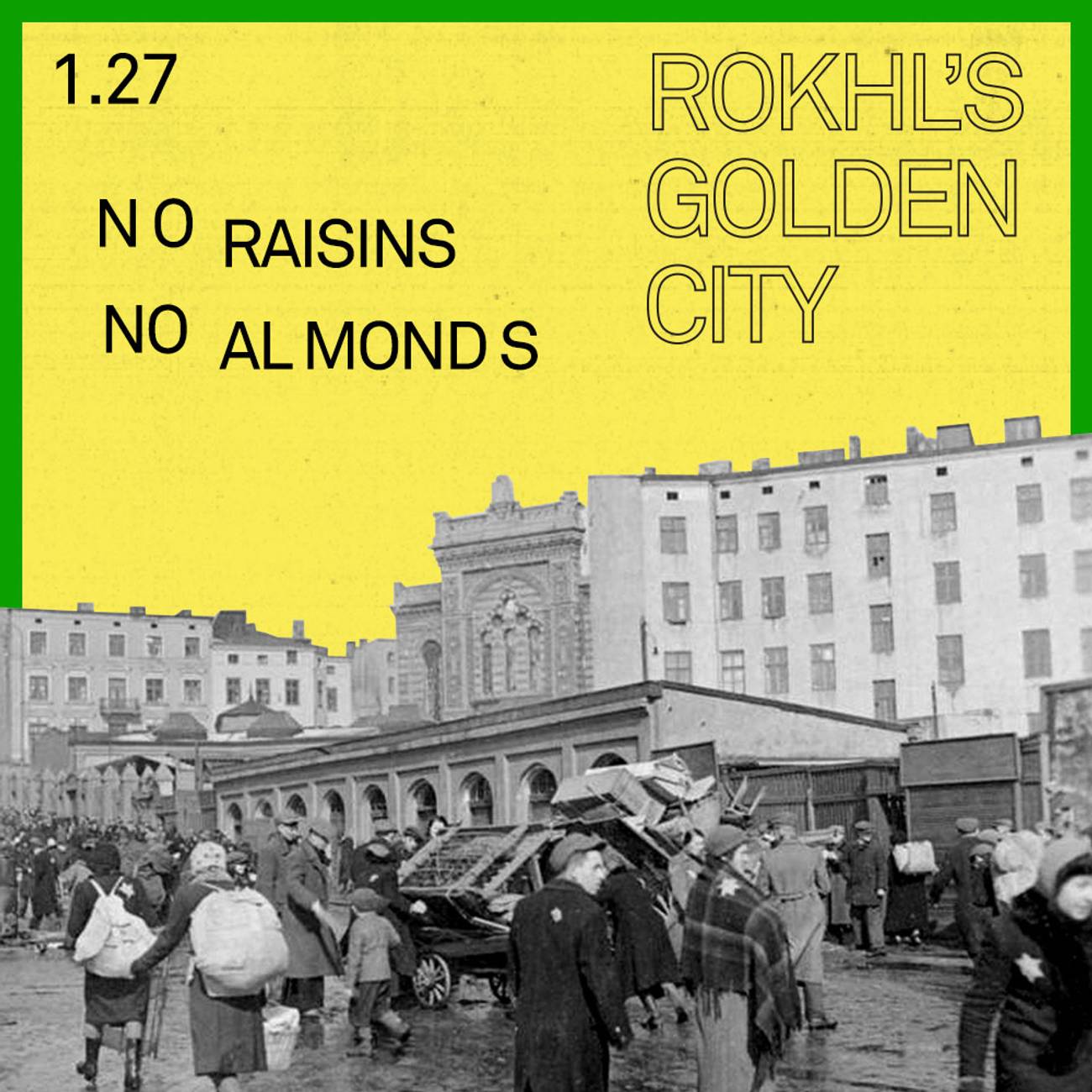

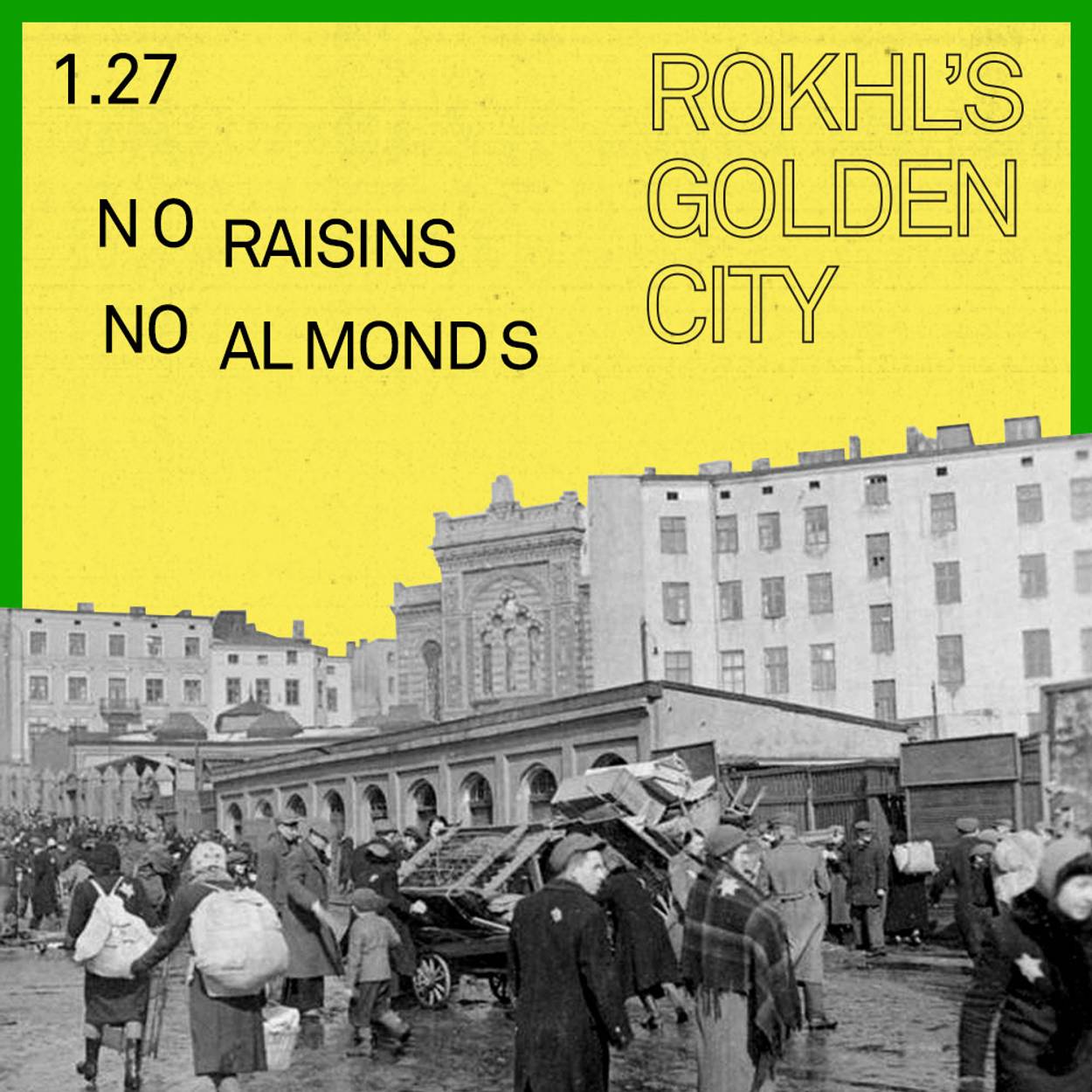

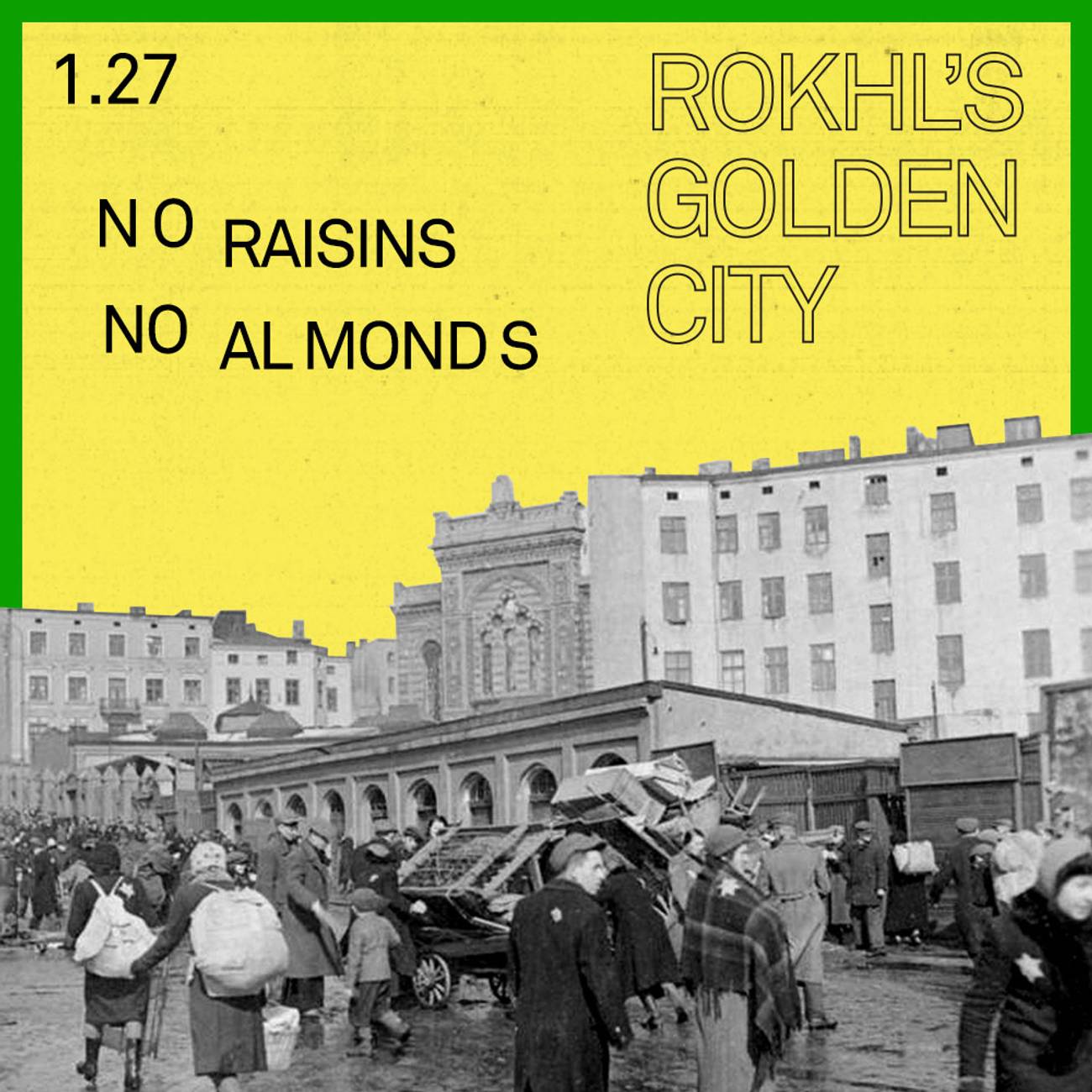

But individual LPs were still a limited, analog technology. Nit Keyn Rozinkes, Nit Keyn Mandln (No Raisins and No Almonds) is a Lodz Ghetto composition, as the liner notes tell us, “A Parody on a Traditional Jewish Lullaby.” It is not mentioned, however, that the best-known version of the song was composed by Avrom Goldfaden, or that the Kovno Ghetto also produced its own Rozhinkes mit mandln parody. The narrative of Songs of the Ghetto was a personal one, and its archive, so to speak, was Brun’s lived experience. But the world of Eastern European Jewry was infinitely interconnected. One LP could only do so much contextualizing.

When Brave Old World released its stunning song cycle Song of the Lodz Ghetto in 2005, it reflected decades of ethnographic collection efforts among survivors, especially their songs. The band worked with Israeli ethnomusicologist Gila Flam, and drew on her 1992 book, Singing for Survival: Songs of the Lodz Ghetto, which featured interviews with survivors as well as archival documents. The CD is a musical masterpiece and Brave Old World earns its reputation as a klezmer “supergroup” at first listen.

But on Song of the Lodz Ghetto, that musicianship combines with an exquisitely fine-tuned ear for the uncomfortable subtleties of human experience. Notably, the band is able to explore a subject that appears nowhere on Brun’s album: the anguished relationship between Nazi appointed communal leaders (the Judenrat) and the residents of the ghetto.

The first song on the CD is “Rumkovski Khayim,” in which it’s related that Rumkovski, the head of the Judenrat, is “sending the whole ghetto to hell” and has “made a good deal with the Angel of Death.” Rumkovski was so hated that when he was finally deported to Auschwitz in 1944, he was beaten to death by Jewish Sonderkommando inmates. With such an infamous figure at the center of the ghetto’s story, the CD fittingly opens with an archival recording of Lodz Ghetto survivor Ya’akov Rotenberg singing “Rumkovski Khayim” and closes with a lush reprise, fading into Rotenberg’s voice once again.

Song of the Lodz Ghetto is a self-contained “musical performance piece” inspired by the songs created by the residents of the ghetto themselves. It uses archival material, but does not spring from the archive. With the advent of the fully integrated digital age, however, I believe we are seeing new artistic forms shaped by those technologies and the unprecedented archival access they provide.

In a 2019 interview for the Jewish History Matters podcast, historian Jeffrey Shandler reflected on the state of Holocaust testimony video archives. There are now thousands of oral histories. “What do you do with tens of thousands of them? How do you make your way through so much material?” If the material is well indexed, you can search and aggregate by topic, “which allows you to create in effect new narratives … transforming [the material] because of the kinds of engagement that it enables through searching and collecting material.”

Though Shandler was speaking specifically about the Shoah Foundation Video History Archive at USC, his insight is equally applicable to a brilliant new project from the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. Established in 1979, the archive now has 4,400 testimonies—12,000 hours of recorded material—in over 20 different languages.

Because the video testimonies have been carefully indexed over many years, it was possible to locate which testimonies contain songs or recited lyrics. In 2018, archive director Stephen Naron set out to invite musicians to record some of those songs. He connected with Brooklyn-based ethnomusicologist and klezmer musician Zisl Slepovitch to lead the project. In 2019, that partnership resulted in Where Is Our Homeland? Songs From Testimonies in the Fortunoff Video Archive, Volume 1. This month, Slepovitch and his colleagues released Cry, My Heart, Cry! Songs From Testimonies in the Fortunoff Video Archive, Volume 2.

Both CDs bring together an astounding variety of musical forms, traditions, and topics. An anti-Semitic Polish song is next to a satirical song composed in Auschwitz, which is next to a popular Argentine tango, adapted to tell the wartime horror of deportations to Treblinka.

When I spoke to Slepovitch recently, we discussed how Songs From Testimonies differs from his many other musical projects. The arrangements, for example, are different from his other albums because of the unique framework of the album. Another factor is the diversity of this material. Said Slepovitch, “I have never recorded an album this diverse in styles, languages, and backgrounds.” Though all different, the tunes feel remarkably fresh, thanks to the presence of his frequent musical collaborators, Joshua Camp, Dmitry Ishenko, Craig Judelman, Sasha Lurje, and Mariana Slepovitch.

The notes for Cry, My Heart, Cry! run to some 30 digital pages, a dazzling work of musical, linguistic, and historical contextualization. Slepovitch brings his command of many languages and his training in ethnomusicology. At times, the story behind the song is just as gripping as its performance.

In his archive testimony, Henri G. recalls how his family moved to Paris in 1932 to escape the anti-Semitism in Poland. But when war broke out in France, Henri and his brother had to escape again. He put on a uniform with the insignia of Marshal Petain and went to the train station with his brother, where they had to fool the patrolling Germans. Henri instructed his brother to sing “Une Fleur au Chapeau” (A Flower on the Hat), a jaunty French scouting song. The song itself became an essential part of their survival. As Slepovitch writes in the notes, the arrangement “attempts to convey the feigned carelessness of the two teenagers running for their lives from occupied Paris.” As sung by Sasha Lurje, this version of “Une Fleur au Chapeau” does exactly that, bringing the listener to a moment of breathless daring and bravery with just a few snaps of the finger.

Each song on Cry, My Heart, Cry! contains a hundred threads leading in every direction, inviting contemplation, as well as further research on the part of the listeners. With the new tools to instantly access and search digital archives, we are seeing new kinds of memory work enabled by new kinds of connections, including the ability to listen and compare these new recordings with the original video clips of survivors singing them.

When I spoke to Naron, he reminded me that there are even bigger things in store for this work. Enabled by the archival software developed for the Fortunoff Archive, Naron is planning to bring Holocaust video archives around the world onto the same platform, making even more space for the kind of creative transformations anticipated by Shandler. For such a somber topic, it’s an unexpected, but welcome, source of optimism.

LISTEN: All audio and video resources for the Songs From Testimonies project can be found on the Fortunoff Video Archive website … There will be a lunchtime performance and discussion of Cry, My Heart, Cry!on April 28, co-presented by YIVO and Carnegie Hall … Brave Old World’s Song of the Lodz Ghetto is streaming and on iTunes …

RESEARCH: Yizkor (memorial) books are another important lens through which we can view the world of Jewish Eastern Europe. On Feb. 16 at 2 p.m. the Museum of Jewish Heritage presents ”Zachor: Yizkor Books As Collective Memory Of A Lost World,” exploring the history, evolution, and impact of Yizkor books.

ALSO: In February, my dear friend Anthony Mordechai Tzvi Russell will be leading a three-session program for the Workers Circle called “In the Midst: Exploring Systemic Racism through the lens of Yiddish Culture.” The first session is on Thursday, Feb. 4: “Injustice and Interpretation: Leyb Malach’s Mississippi.” Anthony will be joined scholars of Yiddish theater and literature Alyssa Quint and Eli Rosenblatt. … Y’all know what a fan I am of Natan Meir and his scholarship on the shtetl margins. In February he’ll be leading a four-session virtual tour called “The Dark Side of Fiddler: Eastern Europe’s Forgotten Jews.” First session Feb. 3. $80 for all four sessions. Register here …. Feb. 10 at 3 p.m. (EST), my friend Caroline Luce will be talking about a topic which is extremely my jam: “California Reds: Young Jewish Communists in the 1930s.” She’ll be looking at young Jewish activists raised in the Yiddish-speaking immigrant milieu of Los Angeles who came of age in the Young Communist League in the 1920s and ‘30s … Jeffrey Shandler is probably the historian whose every work fills me with such intense admiration, bordering on envy. On Feb. 17, he will be giving a book talk in honor of his new book, Yiddish: Biography of a Language, and it’s sure to be brilliant … Also on the afternoon of Feb. 17, the annual Asch Wednesday celebration goes forward, celebrating all things Sholem Asch, with theater, music, film and more … On March 4, the Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience at UCLA will present “Remembering Theo Bikel—Actor, Activist, Idealist,” featuring performances by Daniel Kahn, Arlo Guthrie, and more … Shalom Foundation and Centre for Yiddish Culture will be offering their first ever Winter Mini-Seminar in Yiddish Language and Culture online. Sessions available for intermediate and advanced students. Feb. 26-28 and March 5-7 … Is it Purim already? My friend Shane Baker at the Congress for Jewish Culture has been working on something really special: a new dramatic production of Itzik Manger’s Megile Lider. See it on Feb. 21 … And on Feb. 25, join the Museum for Jewish Heritage and the Folksbiene for a reading of Megiles Ester in Yiddish.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.