The Sound of Music

Rokhl’s Golden City: What makes a song Jewish?

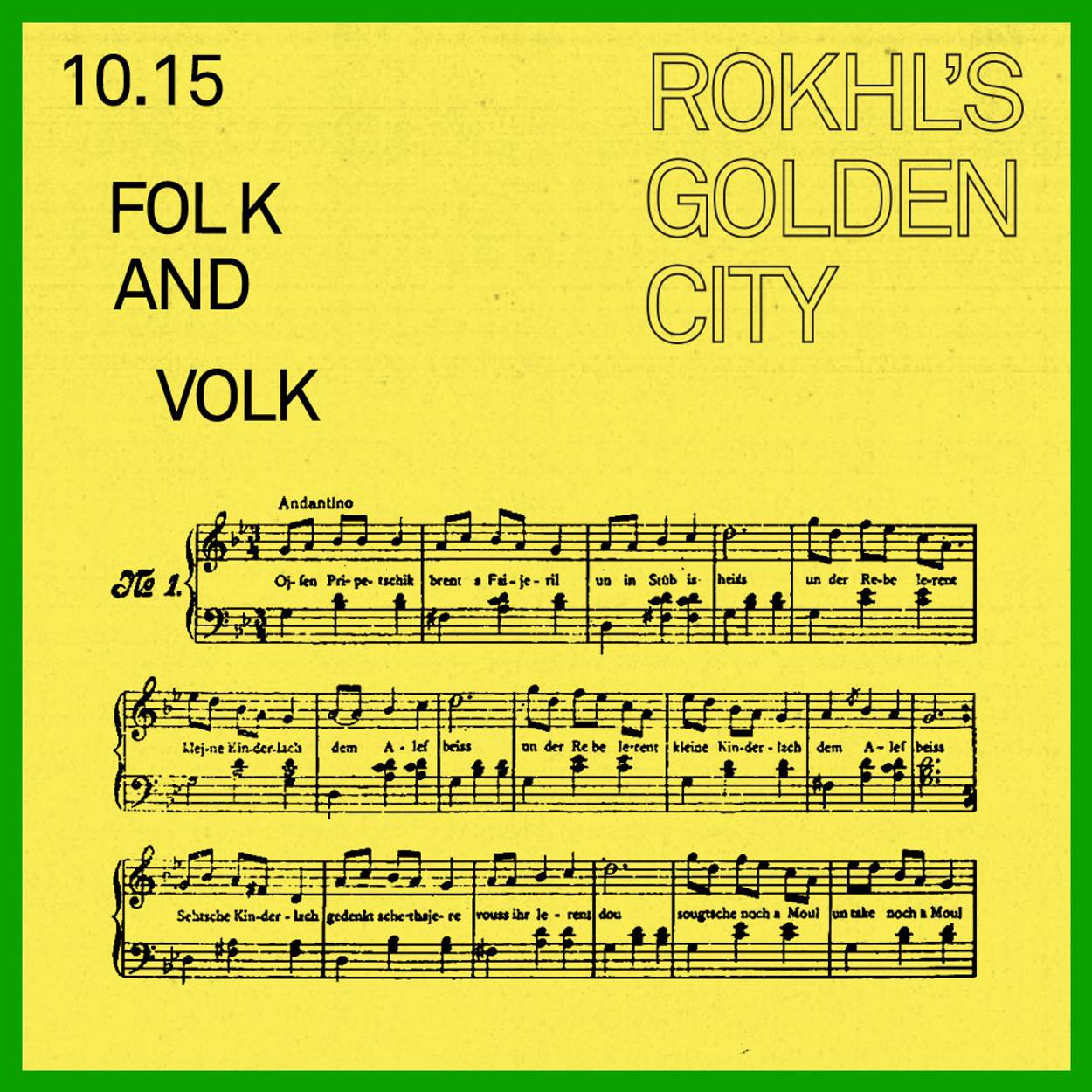

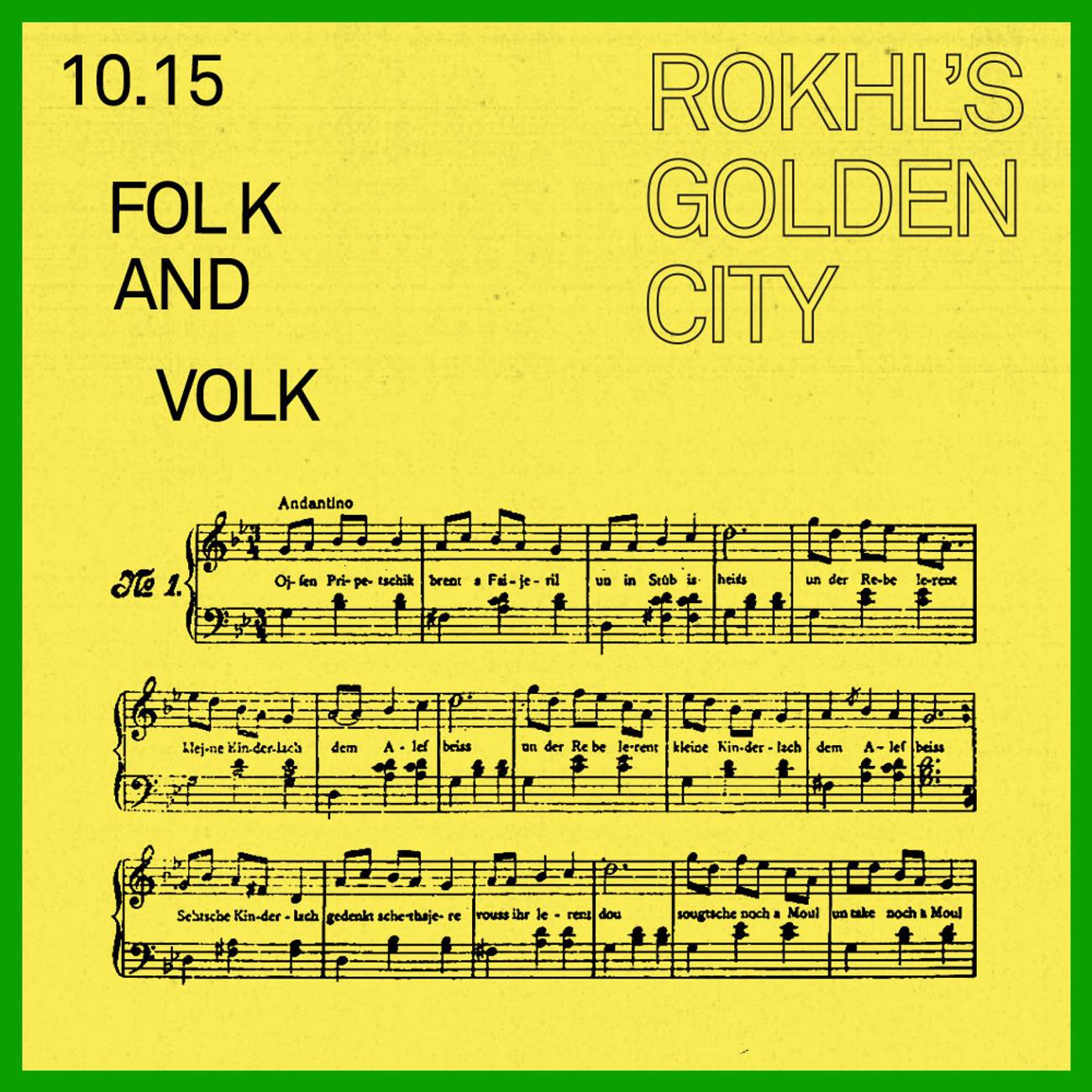

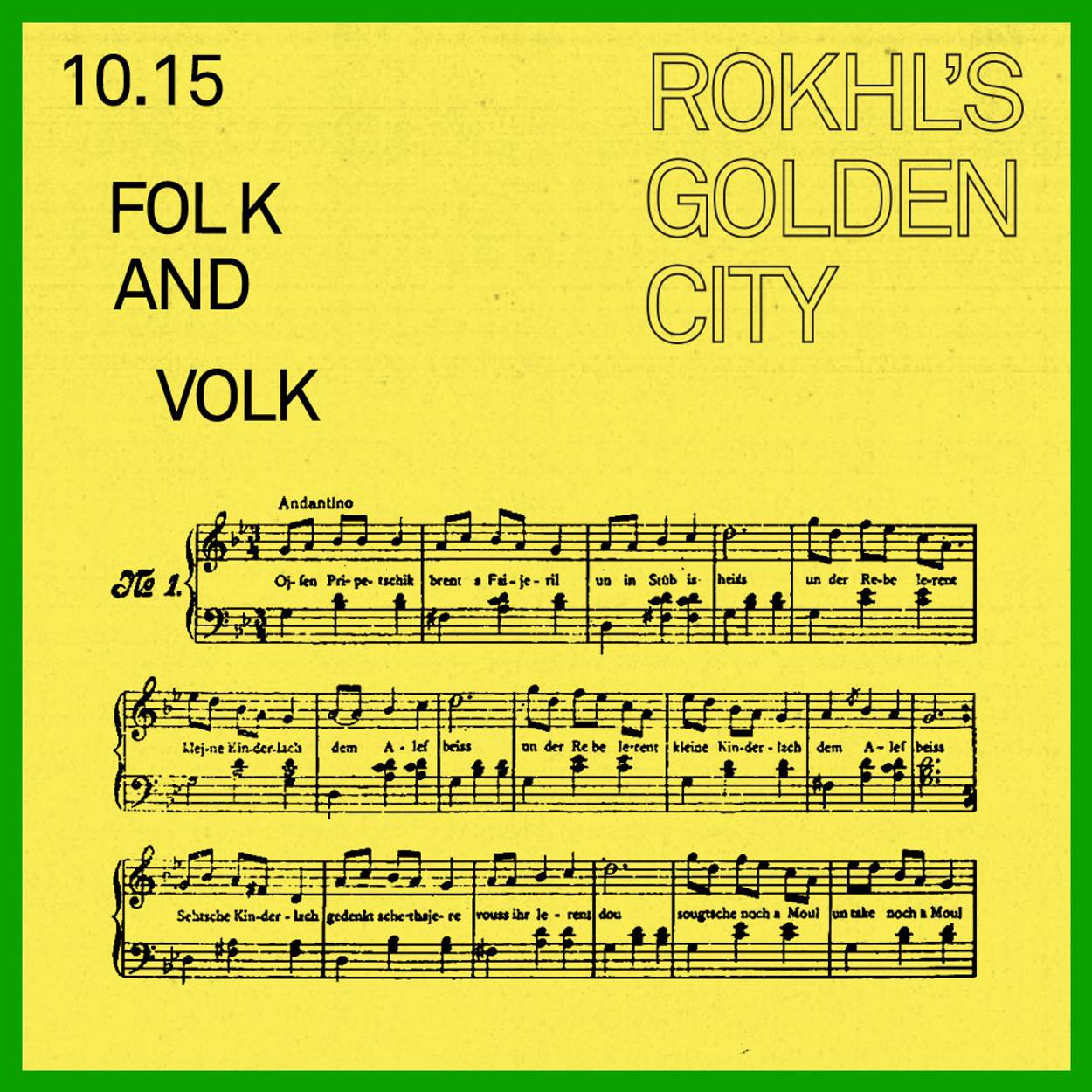

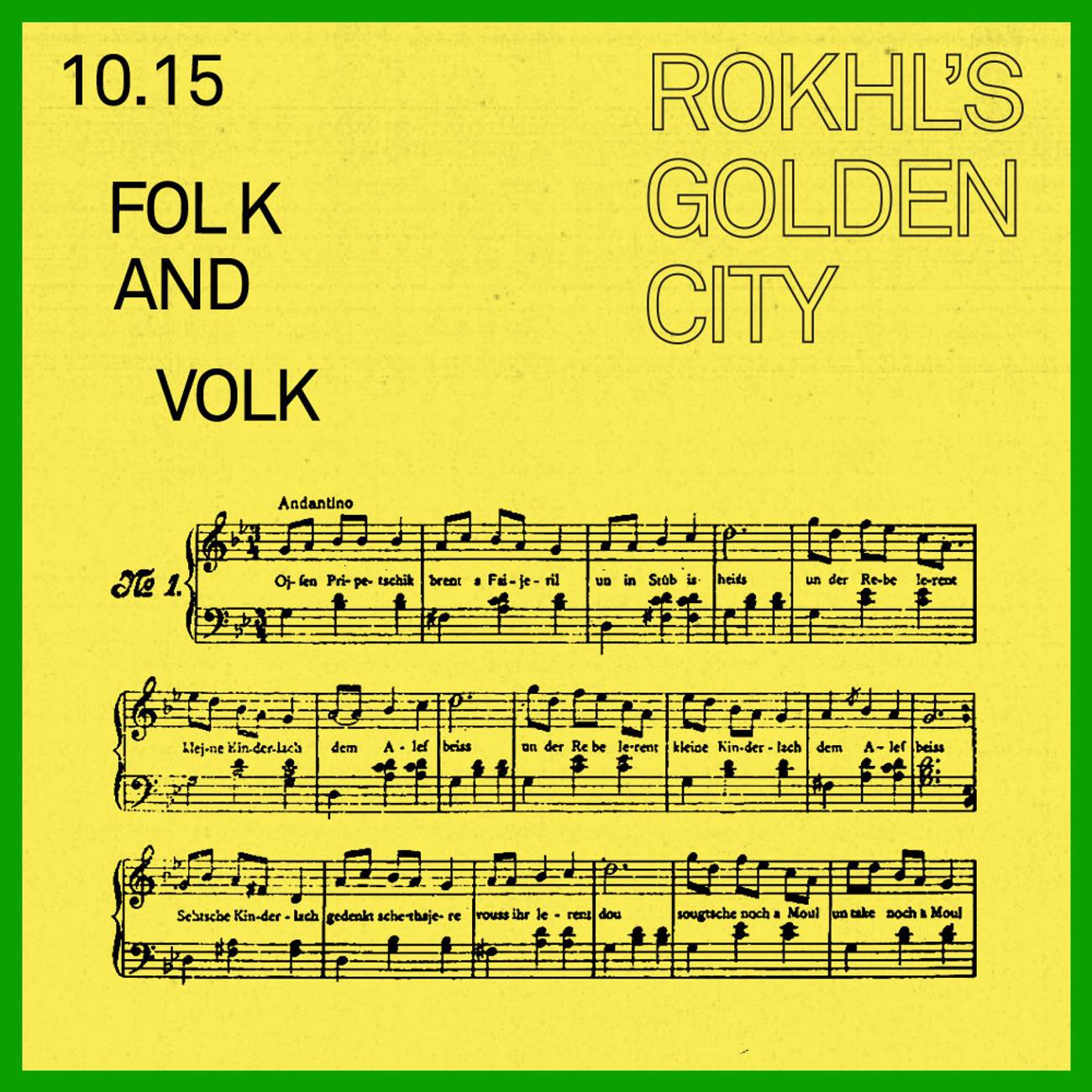

What does Jewish nationalism sound like? “Hatikvah”? You can’t get more nationalist than a national anthem. What about “Hava Nagila”? It’s practically the unofficial anthem of Zionism. Or something like “Oyfn Pripetshik”? Since its publication in a Yiddish-language Zionist newspaper in 1899, Mark Warshavsky’s ambivalently nostalgic “folk song” has been appropriated by a surprising array of Jewish nationalist ideologies, including Soviet Revolutionary, Revisionist Zionist, and Soviet Refusenik. Today, eclipsing its many previous incarnations, “Oyfn Pripetshik” is widely recognized as a musical symbol of Holocaust remembrance, which is, at minimum, a significant facet of modern Jewish nationalism, if not an entire ideology in itself.

“Oyfn Pripetshik” looks back on the traditional Jewish primary classroom. The Hebrew letters are being taught, and the students exhorted to cling to them as they shlep the exile. The song was written by Warshavsky, but its enduring place in the modern Jewish psyche owes much to the work of Warshavsky’s friend, publisher, and hype man, Sholem Rabinovich (better known as his literary persona, Sholem Aleichem).

Rabinovich described “Oyfn Pripetshik” as “simple and genuinely Jewish, not artificial” (prost un ekht yudish, nisht gemelkhokhet). This may have been how the song was understood by the average listener, but it would be a mistake to take Rabinovich’s folksy Sholem Aleichem persona at face value. The publication of Warshavsky’s songs put both of them at the center of the era’s most highbrow debates about Jewish nationalism and aesthetics, debates superbly described by James Loeffler in his 2010 book, The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the late Russian Empire.

If Warshavsky’s songs found immediate and widespread popularity, they had at least one prominent hater. Yoel Engel was a musician, composer, and (just a few years later) polemicist on behalf of the Society for Jewish Folk Music (established in 1908). For Engel and other members of the Russian Jewish musical intelligentsia, the question of Jewish musical nationalism was most heated. In a series of newspaper exchanges between them, Engel accused Rabinovich and Warshavsky of “a grave musical offense against the Jewish people,” saying that they had bamboozled “the Jewish masses by pawning off recently composed popular pieces as true ‘folk songs.’” Not only was “Oyfn Pripetshik” of poor musical quality, according to Engel, in sound and content it was barely Jewish at all!

As a humorless Yiddishist and fellow hater, I have to admit that Engel’s polemic resonates. It’s always bothered me that a song with such a well-known author was understood as a “folk” song. Whatever tender feelings I may have had toward “Oyfn Pripetshik” when I learned it as a baby Yiddishist, those feelings have long been ground to dust and swept away. The tune is melodically cloying and its rhythm unbearably awkward. Of thousands of beautiful Yiddish folk song choices available, the worst possible choice for group singing is somehow always in demand.

But I can only ride with Engel so far. Across Europe at that moment, musicians, artists and thinkers were engaged in the project of Romantic nationalism. A nation’s unique spirit, so the thinking went, would be found in its unique language, literature, and music. In his infamous essay “Judaism in Music,” Richard Wagner accused the Jews having no music of their own—being mere cultural parasites. Engel and his future colleagues at the Society for Jewish Folk Music were engaged in a high-stakes quest to prove Wagner wrong. But there is a danger to engaging with antisemitism and antisemites on their own terms: You may end up affirming the very thing you’re fighting.

Engel and his colleagues went looking for something they could call the unique expression of Jewishness in music. They used “scientific” ethnographic techniques to uncover and describe the musical modes that could be identified as that unique expression of Jewish folk spirit. And, of course, once identified, those modes could be used by the conservatory elites to construct a new-old Jewish musical nationalism.

Sholem Rabinovich, responding as Sholem Aleichem, exposed the queasy logic of that quest, in terms that feel incredibly modern (again, quoted from The Most Musical Nation): “You can talk all you want about Aeolian, Dorian, Mixolydian, and other such high musical words from the ‘Master’s language’ [mlokhim shprakh]. What do we simple people know from this?” Or as Audre Lorde would much later say, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Why should we need the apparatus of European science to know what is and what is not good for the Jews?

However, the terms of Romantic nationalism were not so easily shaken off. “Modal theory” was indispensable to the members of the Society for Jewish Folk Music, as well as widely accepted among other Jewish music elites. “According to this theory,” Loeffler writes in his book, “the national identity of a given piece of music, regardless of its complexity, could be reduced to the basic underlying modal or scalar structure of its melody.”

One society member, Lazare Saminsky, believed modes could serve as “unpolluted musical genes” for new Jewish music. He spoke of it in terms that would make Wagner proud: “No foreign musical growths have ever grown on the core of our traditional synagogue music …” He saw his ethnographic research as isolating “pure specimens” for future compositional use.

Having been shaped by way too many Klezkamp lectures on the theory and practice of Jewish modes, I’m not unsympathetic to certain notions of essential units when it comes to certain kinds of Jewish music. But I also believe that music should be written with pen and paper, not calipers and DNA tests.

I also think that as much as we need to understand and teach traditional Jewish musics in a holistic way, the approach to such “essences” requires a lightness of approach, and an awareness of the conditional nature of Jewish history and culture. My Yiddishland colleague Dr. Saul Zaritt recently published a provocative new work he calls “A Taytsh Manifesto: Yiddish, Translation, and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture.” I can’t do the whole thing justice here, but one of his aims is to sound the alarm as soon as any of us get too close to something we believe to be the “essence” of anything.

Taytsh is an old name for Yiddish, and it brings resonances of translation and cultural contact. Zaritt is speaking directly to his colleagues in Jewish studies, but I think the manifesto is of great interest to those in the field of Jewish culture, too. “It is vital,” he writes, “that current scholarship identify the normative strands of modern Yiddish culture (rather than blankly participate in them), expose the nationalist anxieties that motivate them, and then resurface a taytsh paradigm.”

Rather than searching for a “pure” unit of Yiddishness (or Jewishness), Zaritt’s paradigm is a call for self-reflexivity in the field of Yiddish, as well as multidirectionality and dynamism. Just as importantly, he warns against the collapse of “Jewishness” into a unitary subject—the taytsh paradigm is a banner waved for cultures in contact, always and forever.

So where does that leave the brilliant young men of the Society for Jewish Folk Music? They left an enormous body of work composed in a relatively short amount of time. Unfortunately, that music still comes wrapped in Romantic, essentialist notions of folk and Volk, off-putting to the modern listener. From our perspective, the music of the society represents a unique snapshot in time, when some of the most talented Jewish musicians in the world were imagining themselves into the Western musical canon. And for the most part, their compositions are out of print and unknown to Jewish audiences. How best to approach this complicated legacy?

In the past few years, YIVO has programmed concerts devoted the music written by society members. This October, it will feature the music of Lazare Saminsky, and in November, Alexander Krein. I talked to Alex Weiser, (recent Pulitzer Prize nominee for music) and director of public programs at YIVO. As he pointed out, simply expanding our idea of what Jewish music can be is itself important. For Weiser, familiar genres such as klezmer and khazones, as well as classical compositions like Saminsky’s, are all answers to the question of what Jewish music can sound like. “The audience,” he told me recently, “is best served when we have many different answers to that question.”

LISTEN: Two upcoming concerts in the Sidney Krum Young Artists Concert Series feature compositions by members of the Society for Jewish Folk Music. Oct. 19 at 1 p.m. is “10 Hebrew Folk Songs and Folk Dances by Lazare Saminsky,” performed by pianist Thomas Kotcheff. Register here. Nov. 9, 1 p.m. is “Ten Yiddish Songs by Alexander Krein,” performed by singer Lucy Fitz Gibbon with pianist Ryan MacEvoy McCullough. “These 10 songs reimagine Yiddish folksong texts and melodies in rich and imaginative arrangements for piano and voice.” Register here … And if you can’t get enough about the dangers of music and nationalism, on Nov. 17 at 1 p.m. YIVO will hold a panel discussion called “Nazism, Neo-Nazism And Music.” Register here.

ALSO: I raved about Mark Rubin’s new album, The Triumph of Assimilation, in my column this summer. Now you can join him for music and conversation with the Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience at their Meet the Musician program on Oct. 21. Register here … The Toronto Workmen’s Circle celebrates the 120th anniversary of Itsik Manger’s birth with a lecture by Dr. Eugene Orenstein: “Di goldene pave fun der yidisher literatur.” “Dr. Orenstein will analyze Manger’s work to show how he elevated the Yiddish folk song to the heights of modern Yiddish literature.” Please note that the entire program will be in Yiddish. Free. Oct. 24, 2 p.m. Make sure to register by Oct. 22, here … The Tenement Museum celebrates “Clairvoyant Tenement Housewives” this October. You can watch a Tenement Talk with Golden City favorite Eddy Portnoy (online) or go on a Building Tour (in person) to learn more about the clairvoyants and mind readers who worked from tenement apartments. Talk on Oct. 25, Building Tours Oct. 28-29 … Clarinetist Michael Winograd reunites with his band, the Honorable Mentshn, for a night of high energy freilachs, shers, and bulgars. With very special guest Shane Baker. At Jalopy Theatre in Brooklyn, Nov. 4, 8 p.m. Tickets here … Lorin Sklamberg (Klezmatics) will be featured at the “Common Ground: Mini-Global Mashup #3—Yiddish Meets Argentina” concert on Nov. 21 at Flushing Town Hall. Tickets here.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.