Sweet History

How sugar became integral to the Jewish palate

I have a sweet tooth. There, I’ve said it. Much as I’ve tried to deny and even contain my affection for sweet things, insisting that mine is a savory kind of life, my craving for sugary substances has come roaring back in recent months.

I’ve inclined to attribute my backsliding to both the COVID-generated state of affairs and the political situation, but the truth is I come by my sweet tooth honestly. It’s a part of my yerushah, my family heritage. When I was growing up, no Shabbat in our household was complete without the presence of a glossy confection from the local “fancy” bakery, which, in the way of kids everywhere, was given its own name: No matter its contents, or its official designation—say, Black Forest cake or lemon meringue pie—my three siblings and I called the weekly treat the “special.”

During the rest of the week, my father invariably accompanied his breakfast coffee (and in later years, his cappuccino) with a Danish and, most nights, was given to nibbling away at a chunk of halvah after dinner. My grandmother, meanwhile, prepared a mean gefilte fish, heavily laced not with pepper but with sugar.

In this, I’m not alone. The traditional Ashkenazi Jewish palate made much of the sweet stuff, incorporating it into fish dishes, meat dishes, side dishes, fruit compotes, pastries, and homemade candies. Even when they veered toward the sour, East European Jewish recipes couldn’t resist offsetting that note with more than a soupçon of sweetness, giving rise to sweet and sour cabbage and sweet and sour meatballs, among other things.

What’s more, a predilection for sugar among Ashkenazi Jews continues. As I’ve been given to understand by Leah Koenig, the distinguished culinary authority and Tablet contributor, some contemporary Ashkenazi Jewish communities such as Chabad resort to sugar as a major source of seasoning, not just as a sweetener.

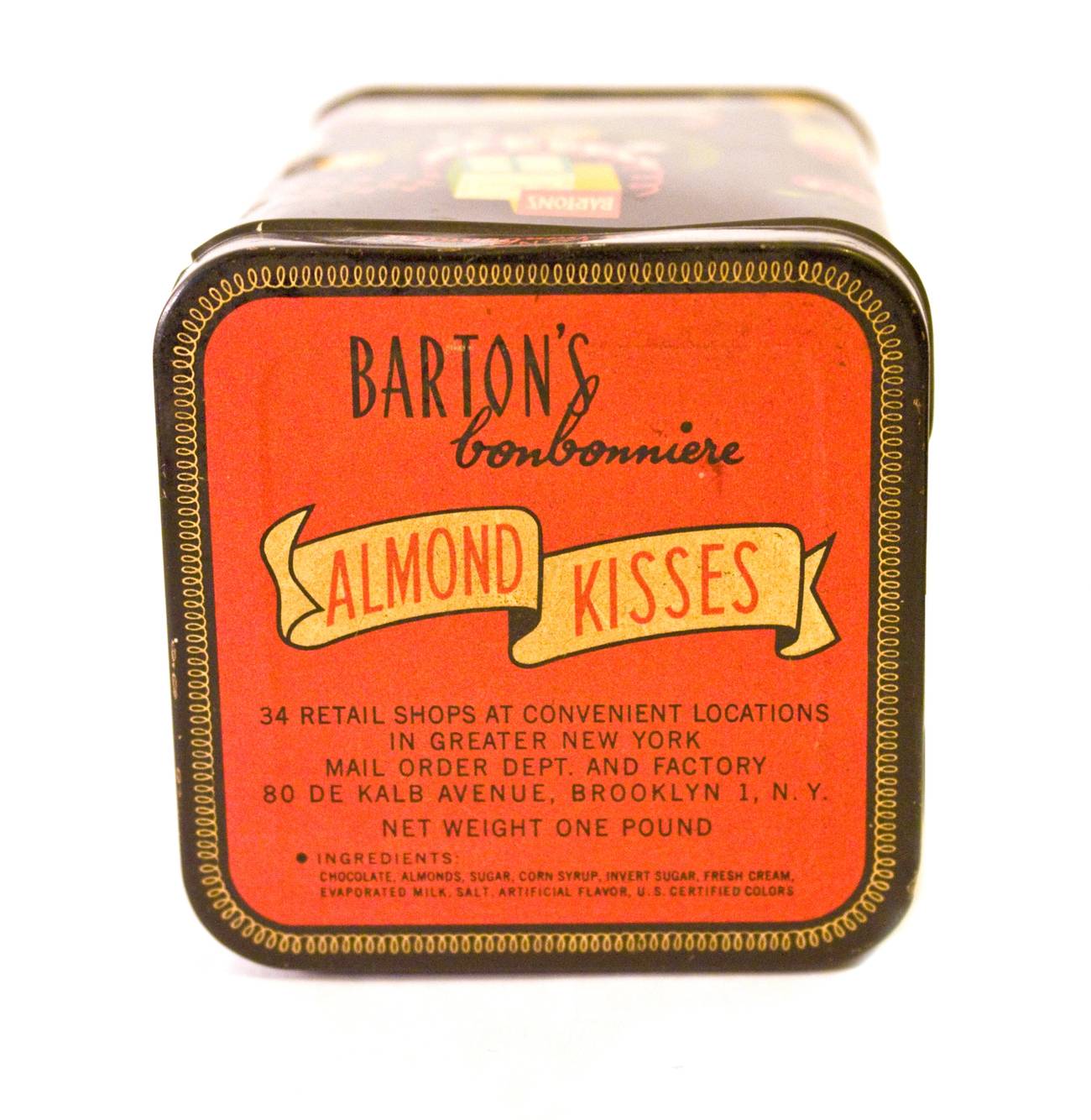

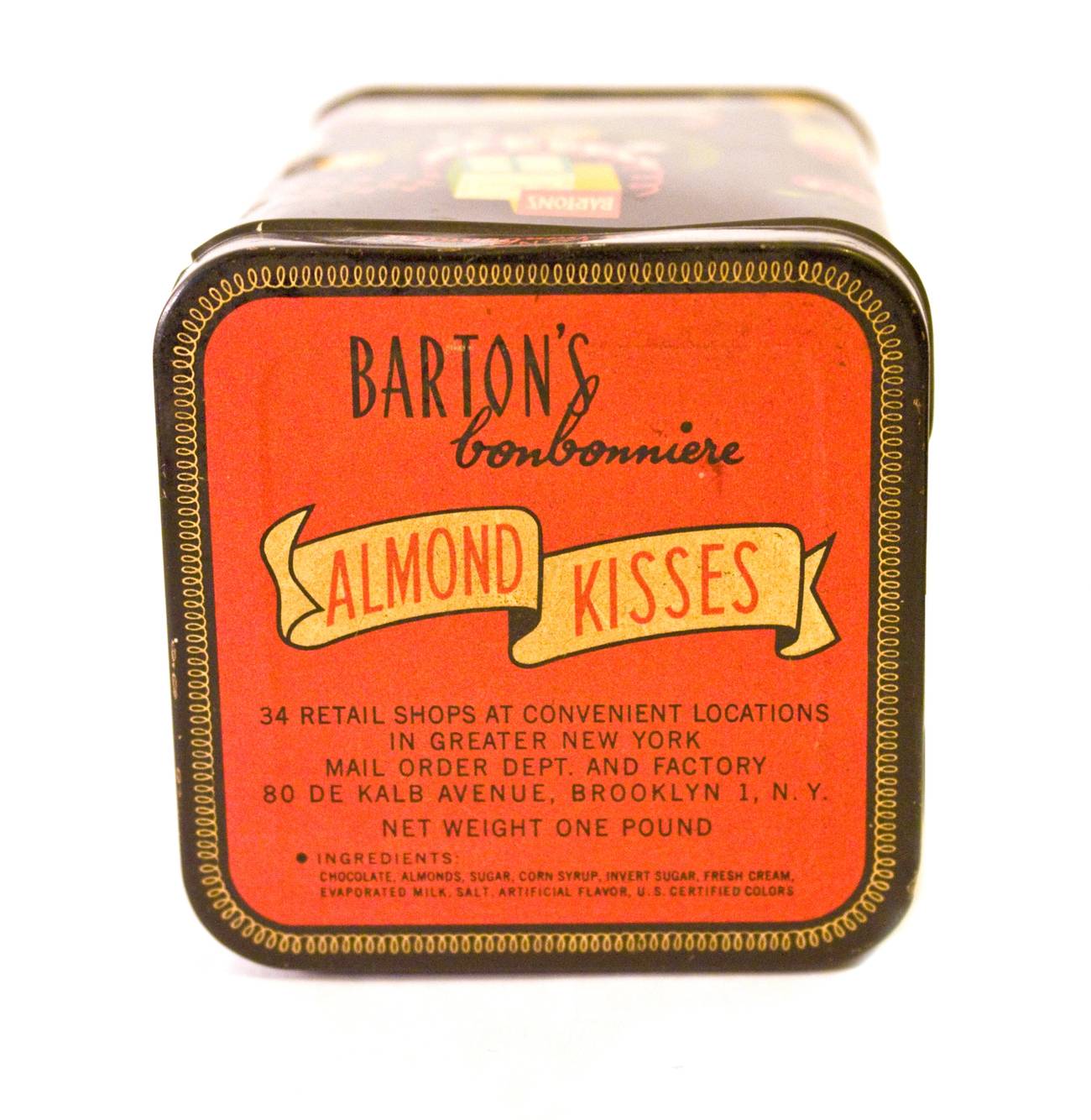

Over the years, entrepreneurs have been quick to capitalize on the Ashkenazi Jewish appetite for the toothsome, transforming it into a commodity. Consider Barton’s Bonbonniere, whose hand-dipped chocolate bonbons were once widely available at any one of its more than 50 stores throughout the greater New York metropolitan area as well as by mail, courtesy of its “Sweet of the Month Club.”

The subject of a lavishly detailed profile in the May 1952 issue of Commentary, the Barton candy empire was known for the “sweet and smooth” taste of its products, especially when compared with those of its competitors. Barricini chocolates, we read, had a tarter edge to them; Fanny Farmer offerings tended to be simpler and blander. To gild the lily, Barton’s candies were kosher, too.

If Stephen Klein—a Viennese Jewish immigrant who, en route to becoming Barton’s founder and president, had apprenticed as a candy maker in his native Austria—had his way, American consumers would think of Barton’s every time they had a hankering for candy, much as they automatically associated soap with Ivory. As for the many Jews among Barton’s loyal customer base, “there is no other candy to buy,” faithfully declared one of their number.

With their magenta and chartreuse striped awnings and handsome, streamlined interiors, Barton’s shops were a cut above the neighborhood candy store, which familiarized legions of American Jewish youngsters, many the children of immigrants, with the likes of the Tootsie Roll—itself the creation of a Jewish immigrant to the United States—and other really-bad-for-your-teeth eatables.

An unsung institution if ever there was one, the local candy store was simultaneously a safe haven and a site of discovery. (Think comic books, for starters, or the telephone. Well before that device became a household staple, the candy store down the block was often the only place that had one.) This modest enterprise propelled many Jewish immigrants and their children into the middle class. “At the beginning is the candy store,” recalled Rose Englander, whose papa operated one on Third Avenue and 82nd Street in Manhattan during the interwar years. For him and thousands of other first-generation American Jews, it was a “decent if arduous way to make a living and bring up a family.”

As late as 1929, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported that 80% of the nation’s stationery and candy store keepers were Jewish. The following year, a study conducted by the East Side Chamber of Commerce counted as many as 516 “candy and soda stores” within the one-square-mile radius of that downtown Jewish enclave, outnumbered only by butcher shops, which totaled 556.

Statisticians, memoirists, and businessmen weren’t the only ones to take note of the collective Jewish affinity for the sweet stuff. Medical authorities also weighed in, pinpointing its role in the etiology of disease, especially when, during the 19th century, the science of doctoring came into its own. As historian John Efron documents in his compelling account Medicine and the German Jews, diabetes—a consequence of excess sugar in the body—was widely known throughout Europe as “Jews’ disease,” or what German doctors called JudenKrankheit. The association between the two persisted in the New World as well, where a celebrated and often-cited study of hospital patients in New York between 1890 and 1900 claimed that diabetes was “nearly three times as prevalent among Hebrews as among any other race or creed.”

Despite widespread agreement within the medical profession on the relationship between diabetes and modern-day Jews, consensus on its origins was hard to come by. Some authorities attributed the disease’s prevalence to history, noting that the Jews, having experienced a “severe environment during many centuries … developed a nervous type easily thrown out of balance,” which rendered them susceptible to the affliction. Others thought it more a matter of diet: The Jews, it was said, were too fond of the pleasures of the table for their own good and tended to eat too much.

Still other experts, assailing the sedentary occupations in which modern Jews clustered, maintained it had to do with a lack of exercise, or, more damning still, with ineptitude in the bedroom. Unable to lead a satisfying sex life, the Jews, it was said by H.L. Eisenstadt in the Zeitschrift für Psychotherapie und medizinische Psychologie, regressed to those moments when they “took delight in that with which their mothers satisfied them during childhood—sweets.” Even those commentators who might have been dubious about this particular variation on a theme conceded that the Jews had a “special liking for sweets and pastries.”

It may well be that this collective predilection had nothing to do with Mama and everything to do with the economic infrastructure of modern Jewish life, especially in Ukraine, where Jews were heavily involved in the sugar beet industry. Though we’re apt to associate the sweet stuff with tropical sugar cane, an alternative form of the commodity—one far less expensive to produce and bound up with free rather than slave labor—began to emerge in the mid-19th century with the expanded cultivation and processing of sugar beets.

Before long, traffic in sugar beets became a global phenomenon, giving rise in the United States to the Beet Sugar Gazette, the “trade journal par excellence in the sugar industry” and an “indispensable guide” to what was going on in places that ranged from Missoula, Montana, to the Ukrainian city of Kyiv. Its pages, thick with advertisements for jute, seeds, and heavy machinery, as well as with updates on the latest technological and botanical advances, attested to the impact of the sugar beet industry on modern life: an international agrobusiness.

Thanks to a combination of factors, from the hospitableness of its soil to what one writer in Scientific Monthly called a “miracle of modern science” and a “triumph of plant breeding,” Ukraine increasingly became a major center of the sugar beet industry. Jewish entrepreneurs, among them Yisra’el Brodsky and his sons, Lev and Lazar (who was known as the “Sugar King”), were at the ready. Drawing on the latest advances in steam-driven technology and an abundant supply of both capital and labor, they first invested in and then developed their own network of sugar refineries which, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, reportedly supplied nearly 25% of all the sugar consumed throughout Tsarist Russia.

Brodsky’s sugar came to be as familiar to residents of the Russian Empire as Domino Sugar was, and still is, to American households. A prestige product, a hallmark of modernity, it loomed especially large in the consciousness, as well as on the table, of the millions of Jews who lived in that part of the world, affecting their palate and heightening their communal pride.

The next time you and I reach for that second or third cookie, let’s bear in mind that it’s rich in Jewish history as well as calories.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.