The Moses Option

Why I converted to Judaism

When I first approached Rabbi Dan Ain of Beth Sholom synagogue in San Francisco about conversion, he kicked off what would become a several-year affair with two questions:

What’s your relationship with Jesus? Are you aware you’ll have to be circumcised?

Jesus and my wee-wee: not usually on the Zoom meeting agenda. (It was a literal Zoom meeting, as we were in the depths of the San Francisco COVID lockdown of 2020.)

Two years later, I find myself standing in the minyan chapel of Agudas Achim Synagogue in Austin, Texas, about to undergo a hatafat dam bris, the ritual circumcision required of converts previously circumcised. Somewhere in the middle, I had to face both the narrow and broad implications of Rabbi Ain’s second question: Was Jesus my homeboy?

He’d at best been an acquaintance, raised as I was inside the Cuban Catholic world of Miami. Shipped off to a Jesuit school, I first read the Torah (though I wouldn’t have called it that) in the scholarly edition, thick as a phone book despite the onionskin paper, and full of footnotes on the Hebrew or Aramaic. To a bookish teenaged boy, the Torah was fascinating and full of sex, violence, and adventure; the gospels were (and are) a preachy snooze by comparison.

For me, the challenge in converting to Judaism from Christianity was convincing myself that, actually, the Pharisees were the good guys in the Gospels and Jesus some delusional hippie. After living in San Francisco and witnessing the triumph of progressive politics there, it was easier to make that mental turn: I wasn’t abandoning Catholicism, but the secularized Christianity that had elevated the worship of hippie delusions into the law of the land and had spawned wokeness as its afterbirth.

Public life in the West these days is a feverish cycle of figuring out which divine victim to elevate, and which world-saving millenarian “current thing” to embrace this week. It’s the secularized sequel to Christianity with all of the grace, chastity, and virtue stripped out leaving only the faith in a victim-prophet and in an imminent apocalypse that will right all wrongs and initiate the Kingdom of God on Earth.

More and more, secular modernity looks like a shaky edifice of convoluted fantasies built over an abyss, and I for one am tired of pretending to take it seriously.

Deranged bouts of apocalyptic fervor are what Christian societies do when they panic (and Jewish ones too occasionally), as true during the Crusades as the less violent online crusades of today. Seattle’s CHAZ mayhem during the “mostly peaceful” summer of 2020 is of a piece with the Münster Rebellion of 1535 that left that city a violent circus. White privilege as original sin, climate change as eschatology requiring repentance, public acts of repudiation and penance that would top The Scarlet Letter … the Christian parallels are almost nonstop.

If you think this argument is a stretch, consider whether nations in the Islamic or Asian worlds occupy their national dialogues with which class of divine victimhood to revere this media season. It’s an absolutely fish-in-water thing you can’t see until you’re outside of it, and then you see it everywhere.

There are of course purist Christian revolts against this latest optimized-for-virality version of Christianity, otherwise known as wokeness. But the trad Christians and woke progressives don’t actually disagree on the dominant moral narrative for our lives, they simply disagree on who to cast in the starring role. Once you’ve taken yourself out of the Christian mindset—and the only non-Christian mindsets accessible to those raised in Western liberalism are Judaism and maybe the classical Greco-Roman world—the moral “horseshoe” going on between the woke and trads becomes obvious. It’s not a diametric opposition at all, and more like debates over which actor played Batman best in the film versions.

Revolts against the impossible moral demands of Christianity aren’t very novel either of course. They typically take the form of a Nietzschean reversion to paganism, such as the online cult of Bronze Age Pervert. Like most movements in the West these days, it’s just a LARP with a cross-marketed podcast or YouTube channel. But paganism has a nasty way of reemerging, rebranded as “vitalism” and couched in some racial or national chauvinism. The fierce desire to reverse the Christian moral inversion of the Sermon on the Mount and “the meek shall inherit the Earth”—to resurrect the worship of the beautiful, the wealthy, and the strong—is forever latent in Christian societies. In reality, rather than online, that resurrected pagan “vitalism” always ends in horrors beyond comprehension and the Jews and Catholic priests shipped off somewhere.

But then there is one final option: reverting to the original form of ethical monotheism itself, Judaism.

To go in that direction is to swim against the historical stream, and to commit flagrant apostasy. Benjamin Disraeli, himself converted to the Church of England by his social-climbing father, was once supposedly asked by Queen Victoria whether he was really Jewish or Christian. His cryptic answer was to say he was the blank page between the Old Testament and the New Testament in a Christian Bible. I’m less ambiguous about it: I’m tearing out the Gospels from my Bible. Like the MacBook owner who gets a bad version of Apple’s new operating system and intentionally reverts to a prior version to maintain some desired piece of functionality, I’m willfully reconfiguring Sinai rather than Golgotha as the site of man’s encounter with the divine.

I often make a very Silicon Valley joke that Christianity is Judaism with product-market fit and a growth team. St. Paul took a bookish religion with every manner of onerous observance (including the one I’m about to painfully undergo), and crafted it into the viral set of memes that would triumph in the dying days of an empire. St. Paul was the greatest growth marketer in human history, surpassed perhaps only by that other famous Jew, Mark Zuckerberg. We shouldn’t begrudge the Christians too much for an unauthorized religious spinoff. They’ve gotten more people reading Ecclesiastes and Psalms and believing in a rebranded version of tzelem elohim than all the yeshivot in the world.

My great Jewish apologia, the personal philosophy of my conversion—my reasons—will be relatively unimportant to the rabbis who will oversee my ascent into Judaism. They will not even ask about my relationship with God. After all, a Jew is as a Jew does. In an orthopraxic religion like Judaism, what we do and how we live defines our membership, not mere belief. And the first definitional thing I must do to become a member, is have my member rather roughly if biblically handled. You see, “ye shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskin” is not something for which there’s an easy workaround. Blood must be drawn.

I arrive at what appears like a theme park of Judaism on the outskirts of Austin, where a synagogue from every major Jewish movement—Reform, Reconstructionist, Conservative, and Orthodox—all share a sprawling compound donated by nice, local Jewish boy (and billionaire) Michael Dell, founder of the eponymous technology company.

I’m led to the minyan chapel by Rabbi Ain, and it’s straight to business, as I’m asked to whip it out in front of three grown men: two rabbinical witnesses and a volunteer congregant mohel who happened to be a doctor. After I’m visually inspected, the mohel approaches with a spring-loaded lancet, like what diabetics use to draw blood for a glucose measurement. Tugging on the side of my todger, he separates a pinch of skin and triggers the lancet into it, sending a brief jolt of painful alarm through my circuitry.

Prick pricked, the mohel hands me a length of gauze and instructs me to apply it where the lancet had struck. I display the gauze pad with an angry, red splotch to the assembled witnesses. HaShem and I have signed our deal.

Except, not so fast. I still have to pass a final hurdle, which is the beit din, or rabbinical court.

I sit in front of a table topped by a few books, and presided over by Rabbi Dan (who’d fled an increasingly woke San Francisco Jewish world for Texas), Rabbi Blumhofe of Agudas Achim, and two other members of the congregation. They drill me:

How Jewish is my household?

Are my children being raised Jewish?

What do I do on Shabbat?

Do I keep kosher?

Here, I throw myself on the moderate mercies of the Conservative movement. While never a lover of shellfish (despite growing up in seafood-heavy Miami), giving up jamón ibérico, a cured ham imported from Spain, the most delicious—treif of treifs—was almost an existential crisis. I briefly tried to invoke pikuach nefesh, the Jewish principle of human life over law, claiming that my Spanish metabolism would seize in a fatal deficiency without regular doses of Extramadura’s finest pata negra. Rabbi Ain wasn’t buying it: Out went the jamonera from the kitchen countertop. Off goes the Wi-Fi router on Saturday too (though I can’t bring myself to do the timer hassle with light switches). I drop into whatever Chabad synagogue is closest on Friday evening if I’m traveling.

Then comes the stumper question:

How do you feel about the acts of antisemitism we increasingly see in our society?

Though I am well aware of the security measures that Jewish communities have been forced to impose—metal detectors, inspecting car trunks when parking at the JCC, constant security—in order to exist even in the tolerant U.S., I misguidedly decide to lighten the mood:

“Doesn’t Texas have legal concealed carry?” I (partly) joke. “Just buy more guns.”

The joke does ... not … land.

One member of the rabbinical court actually glares at me. Rabbi Ain swoops in to rescue me, recounting how during our outdoor Yom Kippur in San Francisco, a passing motorist had yelled “Fuck the Jews!” in the middle of the Musaf service. He explains how he, as I do, brushes off such events as random noise. The other members of the beit din look unconvinced.

They ask me to leave. I mill around in the hall looking at the portraits of synagogue presidents going back to the early 20th century. I hear raised voices, and there clearly is some sort of debate going on. My glib response to the antisemitism thing was surely sinking my candidacy. I had left Christianity to get out of the victimhood game, and I sure wasn’t bringing that baggage to Judaism. As we recite on Rosh Hashanah:

May it be Your will, Lord our God and the God of our fathers, that our enemies, haters, and those who wish evil upon us shall be cut down.

And if the God of Abraham is busy that day, then the IDF and Mossad can step in.

I’m called back in from my nervous pacing; a box of tissues has mysteriously appeared on the table. Rabbi Ain announces that the beit din has accepted my conversion: Antonio Felipe García Martínez will henceforth be known as זבולון בן אברהם, Zebulon ben Abraham.

The court now runs through what are clearly the final, weighty affirmations, the spiritual points of no return. Rabbi Ain stares at me intently as he asks:

In the Talmud, it states that converts must be warned they’re joining a persecuted, exiled people. If they come for us, they’re also coming for you. Do you understand?

I understand.

Are you converting to Judaism by your own free will and volition, without coercion or undue external influence?

Yes.

Do you renounce all beliefs you may have had in any other religion?

I do.

Do you accept the God of Israel as the one universal and indivisible God?

I do.

In becoming Jewish, are you giving up all religious practices such as baptism and communion that might be associated with your former religion?

I am.

Will you support all those who seek to reestablish and revitalize our Jewish homeland by making the State of Israel a part of your life and the life of your family?

I will.

Do you bind your personal destiny to the destiny of the Jewish people?

I do.

As when Abraham was called by God to sacrifice his son Isaac, or when Moses was called by God as he stared, puzzled, at the burning bush: Hineni, here I am.

I embrace Rabbi Ain, and shake hands with the rest of the court, whose mood is noticeably softer.

“Go spend a few minutes in the sanctuary,” commands Rabbi Blumhofe, the shul’s main rabbi. Rabbi Ain and I slink out of the prayer room, pressure finally over, and walk in silence to the main sanctuary.

The synagogue possesses that eerie calm peculiar to places of worship, looking empty of anything or anyone but feeling otherwise. The back wall is a towering backstop of rough-hewn ashlars in Jerusalem stone that recalls the Western Wall. The ner tamid, the eternal flame, flickers over the gatelike doors of the ark. Rabbi Ain and I each slowly swing open one of its heavy doors, revealing the synagogue’s 10 or so Torot.

Their silver finials gleam in the dim light. The velvet cover on the leftmost Torah states: DESECRATED AT KRISTALLNACHT. Per the synagogue history, the 200-year-old Torah had been rolled down a hill and stomped on by Nazi thugs in Ediger, Germany, then smuggled out to South Africa and there restored by a sofer, scribe.

The rabbi and I stand there in mute contemplation of the scrolls.

This is what the Jewish people have relentlessly safeguarded or salvaged from the ravages of time and adversity: the epic story of a fledgling nation chosen from among great empires, all now gone from the face of the Earth, except the very people who authored that story. Via an immense act of collective intellectual will, the Jewish people have made this text the foundation of a civilization that has spanned the globe and endured for millennia through the harshest trials.

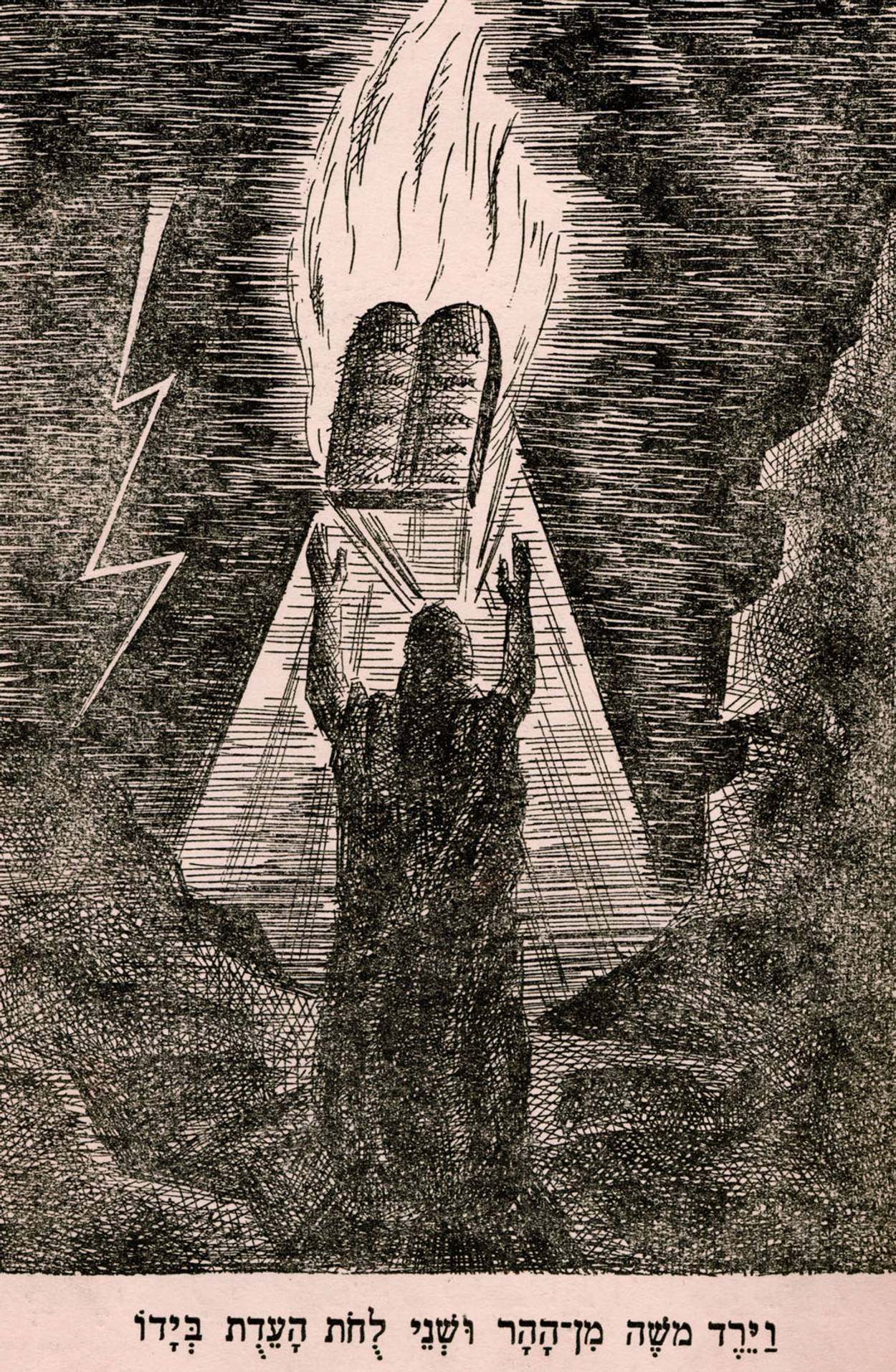

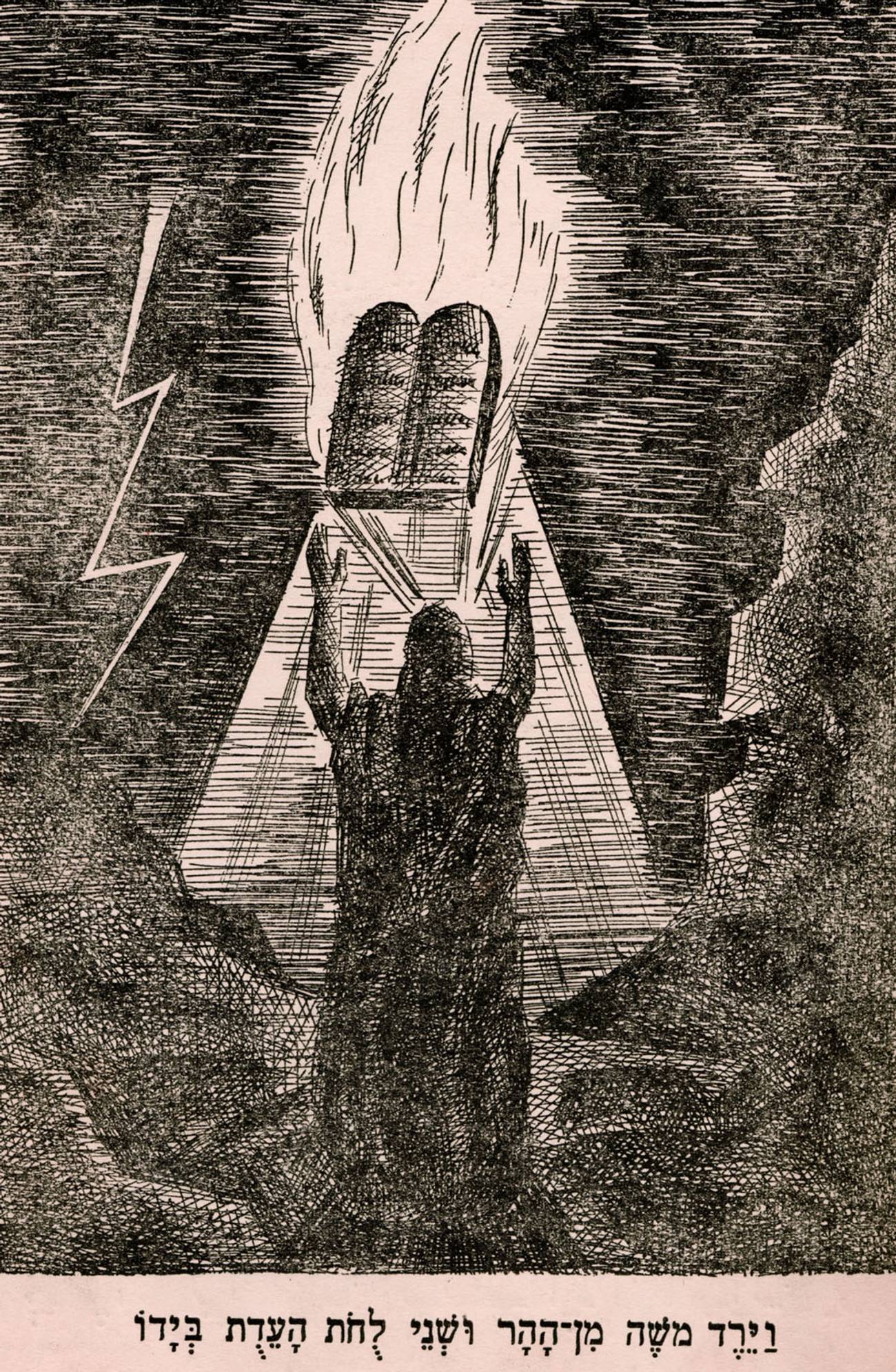

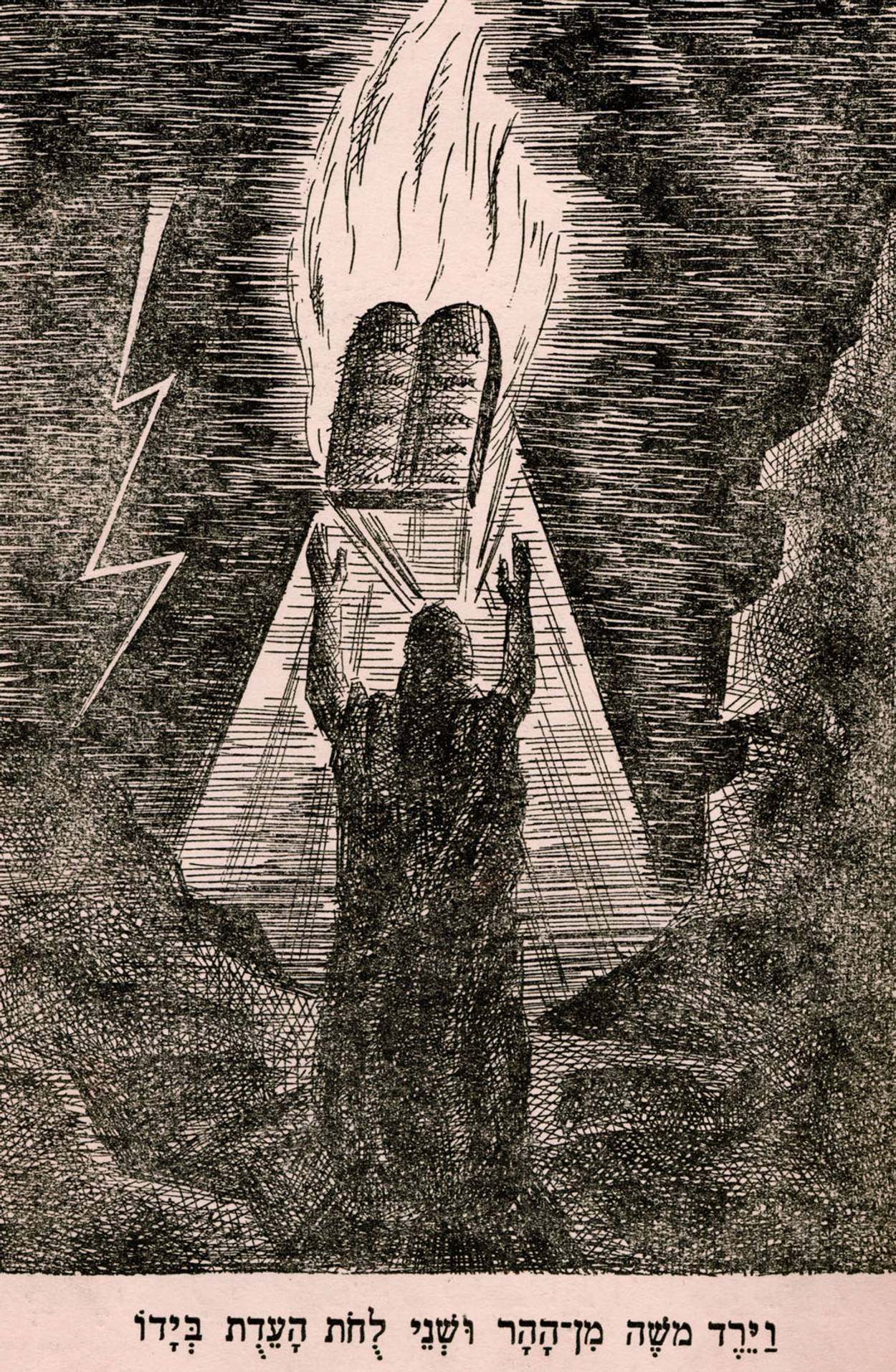

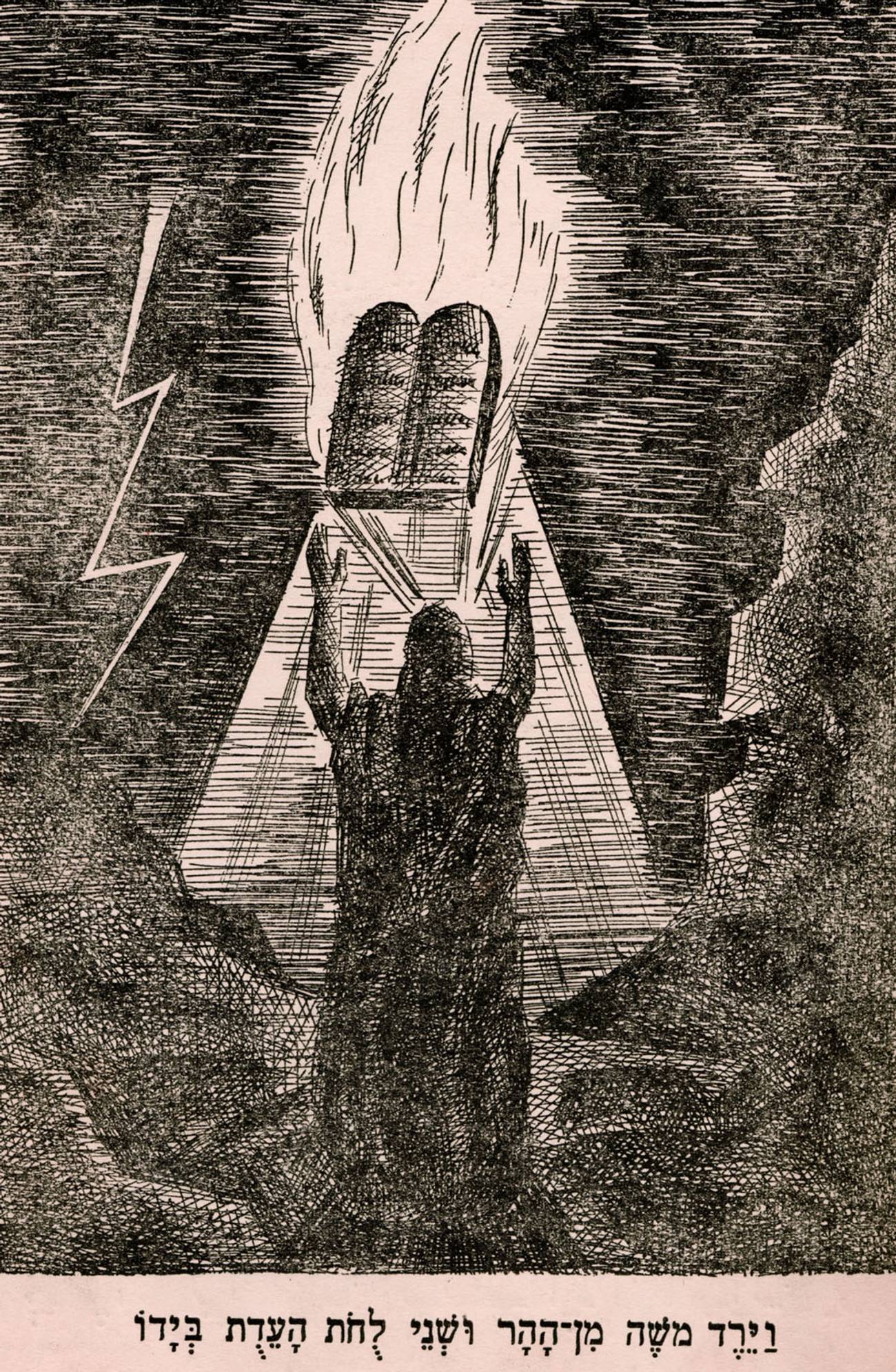

On Thursday, Jews will celebrate Shavuot, an agricultural festival that also commemorates that gift of the Torah to the Jews. Handed down at Mount Sinai to Moses, leader of a Bronze Age tribe wandering the Levant, the Jews have taken their Torah wherever they have gone, imparting its wisdom to their children and converts willing to share their people’s fate.

When that Torah is returned to the ark after reading, a synagogue’s congregation intones: “It is a tree of life to those who hold fast to it.” Stuck in a secular modernity that’s lost the plot, and that no longer knows what it is or where it’s going, I choose to hold fast to that tree of life. I also say, as the loyal convert Ruth once said to Naomi: “Wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there will I be buried.”

Antonio García Martínez is a technologist and the author of Chaos Monkeys, a memoir of life inside Facebook and other startups.