The Ten Commandments Take Shape

In her new book ‘Set in Stone,’ Jenna Weissman Joselit recalls one synagogue’s battle over a stained-glass window

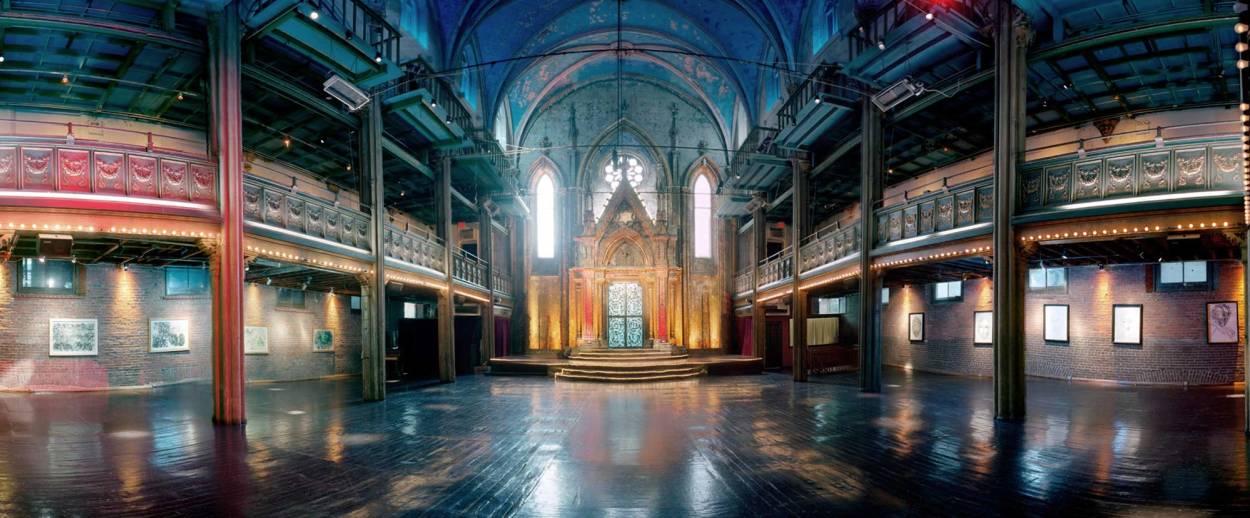

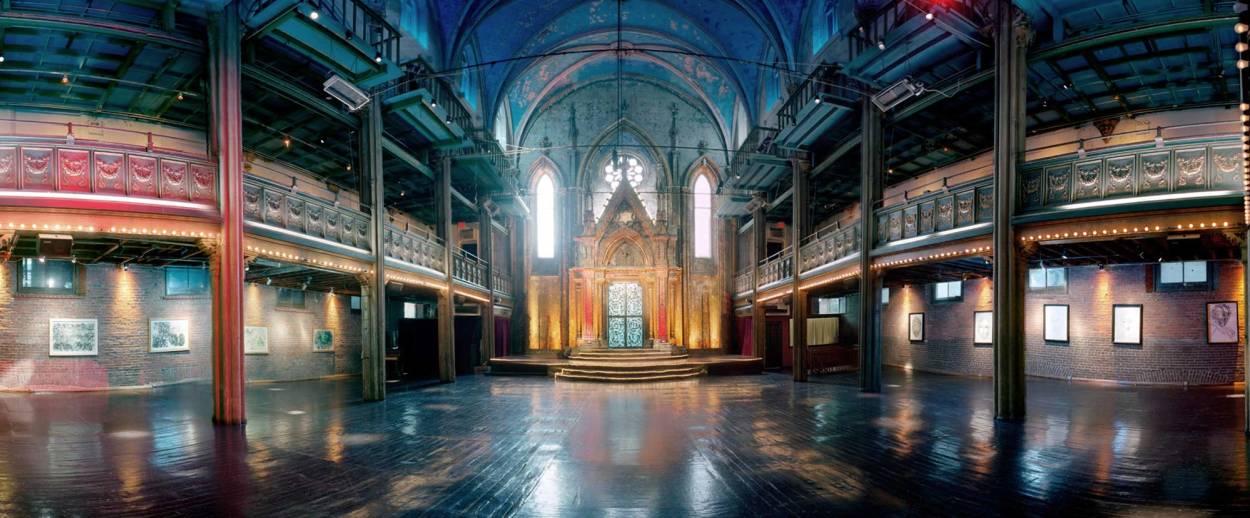

May 18, 1850, was a banner day in the life of Congregation Anshi Chesed, a traditional synagogue in the heart of New York’s kleine Deutschland, the city’s preeminent German neighborhood. Several hundred of the congregation’s members, along with some of the city’s most prominent officials and a “great many other persons of distinction,” gathered together on that spring afternoon, crowding the area’s narrow byways, to dedicate the congregation’s spanking new building on Norfolk Street. Clutching a small card of admission—“not transferable,” it read—they jostled for admission to the Gothic Revival–style synagogue, the largest in the city, a structure whose ambitious proportions dwarfed all the other buildings in its immediate vicinity. A proud, and decidedly modern, urban presence, Anshi Chesed, also known as the Norfolk Street Synagogue, was said to be in step with the “progressive feelings of the age,” as well as the very last word in stylishness. Its architect, Alexander Saeltzer, had made sure of it. An up-and-coming professional in his early 30s who hailed from and was trained in Berlin and who, only a few short years later, would go on to erect New York’s storied Astor Library and its Academy of Music, Saeltzer adorned the exterior of his red-brick building with “ornamented turrets” and its interior with a “mammoth,” three-tiered chandelier from which hung 48 gas jets, then the height of novelty.

The Norfolk Street Synagogue also contained a prominently situated stained-glass window that depicted the Ten Commandments. As stunning as the building’s exterior turrets and as modern as its chandelier, it floated right above the ark that contained the Torah scrolls, commanding the attention of those seated in the pews below. The window’s unusual shape also drew the eye. Instead of embedding the 10 prescriptions within the rigid and customary geometry of two tablets, Saeltzer had them marching freely within the circumference of a circle. These Ten Commandments were in the round. More like the spokes of a wheel than the flat inscriptions on a stele, each “Thou shalt” and “Thou shalt not” was housed within its own unit of glass. To heighten the effect, a series of 10 petal-shaped panels occupied the center of the composition.

A rose window by any other name, the synagogue’s stained-glass salute to the Decalogue cascaded bands of color unto the ark, illumining it much as the Ten Commandments illumined Jewish life. You could almost hear the architect talking up the fine points of his creation: how its circularity expanded the space; brought abundant light into the sanctuary; represented a modern, more inclusive use of one of the cardinal principles of ecclesiastical design; and signaled the congregation’s forward-looking approach to modern Jewish life, its willingness to open itself up to new ideas and abstractions even as it remained true to its faith. The press agreed, singling out the window for high praise in its account of the dedication ceremonies. “This stained glass has a very pleasing effect,” observed the New-York Daily Tribune, whose detailed coverage of the proceedings ran to six columns of newsprint. “The Commandments, instead of being on two tablets, are each on a separate pane of glass, around the window, surmounting the Ark,” it pointed out. The Asmonean, a weekly New York Jewish newspaper nearly as new as the Norfolk Street building, felt the same way. It too highlighted the unusual configuration of the window, noting how it “diffused a pleasant hue over the gay array of blooming faces with which the galleries were crowded.”

Thrilled at first by the positive publicity, the members of Anshi Chesed soon changed their tune and, in the time-honored tradition of congregants everywhere, began to grumble and murmur darkly about their distinctively configured Ten Commandments window. The minutes of the synagogue, which dutifully record this and other instances of congregational dissension, contain scarcely a clue about the identity of the naysayers. Did they represent the more pious members of the congregation? The more recently arrived? The minutes are also frustratingly silent on what set things off. Surely, Anshi Chesed’s congregants, or at least those who served on the building committee or on its board of trustees, knew in advance of their sanctuary’s consecration what the Ten Commandments window was going to look like. It was unlikely that the first time they set eyes on or heard about it was at its public unveiling, especially since Saeltzer had consistently made a point of showing the synagogue board a series of drawings of the sanctuary’s other features. Then again, as anyone who has ever worked with an architect or an interior designer knows all too well, there is often a gap—a big one—between what the client has in mind (or understands) and what the artist actually devises. Perhaps this is what happened between the congregants at Anshi Chesed and their architect, and that growing discontent with his depiction of the Ten Commandments was rooted in a difference of both perception and expectation.

Establishing what they knew and when they knew it is an elusive bit of business. But one thing is certain. Once they beheld their newly consecrated Ten Commandments window, a vocal contingent of worshippers insisted it had to go, hang the expense and the architect’s feelings. Did they find it ugly? Ungainly? Much too showy and colorful? Perhaps even a tad irreverent? Were they concerned that Saeltzer’s rendition did the Ten Commandments a disservice, rendering them too abstract, too novel, too modern by half? Would they have preferred to have dispatched them in marble rather than in stained glass, and in the shape of a rectangular tablet rather than a circle? Would they have wanted to see them affixed to the ark, their usual placement, rather than hover above it? Questions beget more questions—but few answers. Once again, the extant sources give us no information. Clearly, though, something about the Ten Commandments window did not pass muster with the Jews of Norfolk Street.

As momentum for its displacement accelerated, Anshi Chesed’s lay leaders decided to quell further dissent within their ranks by forming a committee. The committee approach to problem-solving had recently become a regular feature of the congregation or shul, as it styled itself in Hebrew in its minute books. Committees sprang up like mushrooms, a testament to its newfound democratic ethos: There was a committee to monitor decorum, especially among the “ladies” who were “requested earnestly to abstain entirely from holding loud conversations during divine service”; a committee to look into the prospect of introducing gaslight into the Norfolk Street building as a whole; and a committee to purchase a clock and one to distribute spittoons. And now, dutifully drawing on the Hebrew words for the Ten Commandments, Anshi Chesed decided to constitute its very own “Committee on Aseres hadebros,” whose members—Messrs Abrahams, Bernheimer, and Stern, but not a Moses among the three of them—set out to repair the situation. Contemporary readers might find the name of the committee somewhat presumptuous and its mandate a particularly amusing proposition, but at the time nobody looked askance. Those who appointed the committee, and those who constituted it, took their charge quite seriously.

As its first order of business, the Committee on Aseres hadebros sought the counsel of “competent persons” to determine what the Ten Commandments should actually look like. By “competent persons,” the committee did not have in mind an artist or even a biblical scholar so much as a rabbi—which, at the time, they lacked. The previous rabbi, Max Lilienthal, had resigned his post in a huff shortly before the congregation had decided to build itself a sparkling new facility, and he had not been replaced. Bereft of a rabbinic presence, Anshi Chesed managed to fend for itself in most things, trusting to its lay leaders. But this unwieldy situation called for an authoritative voice, someone with the clout and standing to resolve it, once and for all. Accordingly, the Committee on Aseres hadebros sought the counsel of a higher religious authority (whose name, curiously enough, was not recorded), to whom it put the following question: “Whether the Ten Commandments (Aseres hadebros), as they are fixed at present, may remain as they are, painted in a circle on stained glass or if it is against the din [Jewish law] and ought to be fixed in the usual way on two tablets?” By framing their question as a matter of Jewish law, they looked for a rabbinic seal of approval on their distinctively shaped Decalogue: Was it kosher or not?

Much to its disappointment, the answer the committee received—and in relatively quick order, suggesting that its author lived in America—did little to resolve the congregation’s quandary. The rabbinic response read, somewhat lumberingly: “There was nothing in the laws which prescribes any form, consequently, that it is not against the din to have them fixed as they are at present, but that they are, as a general thing, fixed differently, namely on two tablets, and that they have never been seen put up in a circle.” Anshi Chesed’s members wanted to know categorically whether there was a right way or a wrong way to depict the Ten Commandments. But in lieu of a flat-out, clear-cut ruling, they were told yes and no. Yes, the version of the Decalogue that adorned the interior of the Norfolk Street synagogue was highly unusual, but no, it did not contravene Jewish law. This was not at all what the committee wanted to hear. It had hoped for a definitive statement; they received a nuanced one instead.

And there the matter rested. But not for long. In the months that followed, many of the worshippers who occupied the pews of the Norfolk Street synagogue continued to feel uneasy in the presence of their newfangled Ten Commandments. Adding to their discomfort, they had gotten wind of some really bad press written by a gentleman who styled himself “Honestus.” A visit to Anshi Chesed had left him in such a state of high dudgeon that he felt compelled to put pen to paper and rail: “I have observed of late, a disposition on the part of certain Israelites … to attempt what they term improvements in matters and things appertaining to our religion.” But they go too far and end up “obliterat[ing]” those “peculiar characteristics that has [sic] ever marked, and in my opinion ought to mark, the Jewish place of worship,” he wrote hotly within the pages of the high-toned Occident and American Jewish Advocate, invoking Congregation Anshi Chesed, whose much-vaunted stained-glass window represented a glaring, and woeful, instance of this contemporary trend. As Honestus would have it: “So great has been the desire for originality and improvement, that the very Ten Commandments, which have always been written on tablets to resemble the shape we are accustomed to see … are altogether divested of their outward character that could the prophet himself see them, I question his being able to recognize them in their new and novel appearance.” Anathematizing novelty, Honestus’s blistering attack made it seem as if Congregation Anshi Chesed had committed the most egregious of sins: deliberately cutting itself off from its roots, even turning its back on Moses.

Amid such fierce and fighting words, some of the more unsettled members of the community picked up the gauntlet Honestus threw down and, determined to re-establish their synagogue’s bona fides, its fidelity to tradition, began to agitate anew for the window’s removal. Its champions, meanwhile, stood their ground. They liked what they saw and were not about to relinquish this decidedly modern version of the ancient text without a fight, Honestus and his opinion be damned. Besides, the cost of removing the window would have been prohibitive. The congregation was already in debt and in the protracted process of paying the bills of its architect and bricklayer, plasterer and upholsterer, and, and, and. It simply could not afford the expense of taking down this stained-glass Decalogue and replacing it with another.

Lest matters continue to fester, splintering the congregation in two, the synagogue’s lay leaders came up with a plan that was nothing short of Solomonic. To satisfy its champions (and architect), the window would be retained. But to satisfy its detractors, the Committee on Aseres hadebros was reinstated and charged with a new mandate: To “get tablets made and to have the Aseres hadebros inscribed therein as it is more appropriate to have them fixed so”—which it did. In an eerie evocation of the biblical story in which Moses, having angrily dashed the first set of tablets on the ground, ends up fashioning another set, the Norfolk Street Synagogue followed suit, augmenting its original commission with a second one. Like their ancestors of yore, these latter-day Israelites of the Lower East Side could also claim a multiple set of Decalogues to their name. With history on their side, they now boasted two in-house versions of the Ten Commandments: an innovatively styled, circular Ten Commandments rendered out of stained glass and a traditional set of tablets, fashioned out of marble, which, as the minutes somewhat inelegantly put it, were “finished in the style as agreed upon [by the] committee on this business.” Set squarely atop the ark, the more customary position, the new tablets acted as a counterbalance to the autonomous, eye-catching stained-glass window. Its impact dulled, the visual equivalent of a second fiddle, the latter remained, untouched and intact, well into the 1970s when vandals made off with it, leaving a series of gaping holes where once the Ten Commandments had diffused a pleasant hue.

At first blush, what happened at Anshi Chesed in 1850 is a familiar enough story: A modern gesture, be it aesthetic or liturgical, comes aground on the shoals of tradition. On Norfolk Street, tradition—or what the minutes characterized as the “usual,” or the more “appropriate,” way—took its cue, as well as its form, from the Bible, where the Ten Commandments were tersely described as being inscribed on two stone tablets, no more, no less. Anything else, any alternative interpretation of either material or form, would seem to fall wide of the mark, outside the pale of Judaism, both literally and symbolically. The congregation’s novel Ten Commandments, neither fashioned out of stone nor resembling a tablet, contravened tradition at every turn. No wonder its members had misgivings; they had history, much less Moses, to answer to.

But there is more to the story than resistance to change or the heavy hand of the past. What distinguishes this particular breach of tradition from any other is its physicality or, more to the point, its relationship to shape. A circular Ten Commandments, unlike anything the congregants of Norfolk Street or, for that matter, other American Jews had ever encountered before—and have not encountered since—shook things up. A statement of contemporaneity rather than historicity, it startled rather than reassured. The novelty of its shape heralded change rather than constancy, threatening to undo the comforting, and familiar, symmetry of the age-old text. The Ten Commandments, after all, were meant to last. A symbol of permanence and continuity—an avatar of stability—as well as a covenant, the tablets were intended to endure through the ages. Time yielded to the Ten Commandments, not the other way around.

A circular Ten Commandments upset the established, time-worn order of things. It was also hard to read. Given its circularity, you could not easily tell where one commandment began and another left off: In which direction—right or left—did they move? Clockwise? Counterclockwise? As much a symbolic challenge as a literal one, Saeltzer’s vision occluded the parallelism with which the Jews had long understood the relationship between the first and second halves of the 10 prescriptions. At Norfolk Street, parallelism went out the window: Goodbye to all that. To compound matters, the compact size of each pane of glass did not allow much room for a full transcription of the text, making it hard, now, as then, to discern which commandment was which. Were they numbered one through 10, or I through X, or, better yet, aleph through yud? Did they draw on the first word or two of each commandment? Contemporary sources do not tell us; they are mute on the matter. Studying what remains of the window is not much help either. Only its silhouette, shrouded in plastic, remains on view these days at the Angel Orensanz Foundation, which now inhabits the building.

I was determined to see for myself, an adventure that had me first dangling precariously from a topmost balcony in an effort to get as close to the window as possible and then high up on an exterior rickety fire escape trying to see from the back of the window what I could not make out from the front. Like those before me, I had difficulty in figuring out the literal expression of Saeltzer’s scheme. I strained to match various images in my mind’s eye to the space and came up empty-handed. I descended from my perilous perch, none the wiser and no closer to resolving this artistic puzzle.

My exertions did yield something, though. Apart from relief on being on solid ground, I took away with me a heightened understanding of the window’s symbolic import and with it, a greater understanding of where it fell short. By emphasizing the circularity of the Ten Commandments, the architect had sought to enhance the fluidity, the resonance, of the millennial words. Round and round they went, from one generation to the next: always relevant, always in play. A noble conceit, to be sure, but something got lost in translation, a sacrifice to visual innovation: legibility.

Instead of inspiring the congregants of Norfolk Street, the unprecedented circularity of these Ten Commandments mystified them. It disrupted the meaning of the ancient prescriptions so completely that these antebellum American Jews did not know what they were looking at: Were these Ten Commandments intended as a theological assertion or as a design element? Making much of their confusion, the Norfolk Street congregants extrapolated further, hitching the fate of their stained-glass window to the future of American Judaism. They came to see their Decalogue, its roundness in full flower, as a slippery slope. If the shape of the Ten Commandments could be altered beyond recognition, they wondered fretfully, what of the future of Judaism? Might it shift its shape too? That prospect, a leap of faith, was one that Congregation Anshi Chesed was not quite willing to contemplate, much less make.

And that was just the half of it. As it turned out, the “usual way” of rendering the Ten Commandments encompassed both American and Jewish traditions. Drawing on scriptural precedents, most New Yorkers conceived of the Ten Commandments as a set of tablets. The stuff of altarpieces, illustrated prayer books, Sunday school primers, clocks, watch fobs, and needlepoint samplers, as well as churchly stained-glass windows, the Decalogue was envisioned, time and again, in rectangular terms. By the mid-19th century, its geometrical proportions were fixed, not fluid, prompting the nation’s Christians to identify the Ten Commandments with two tablets. As far as the disgruntled members of Congregation Anshi Chesed were concerned, it was worrisome enough that their circular window did not conform to traditional Jewish depictions of the Ten Commandments. That it did not conform to American notions of the Ten Commandments either generated a double whammy of a predicament. The oddly shaped Ten Commandments enhanced rather than subdued the mysteriousness of the Jews.

That state of affairs, or “business,” as the minutes briskly put it, could not be countenanced, especially in New York in the 1850s, where the prospect of finding common ground was increasingly touted as a social good, a benefit to both Jews and Christians. “It is pleasant to observe,” observed the Christian Examiner only a few short months before Anshi Chesed’s consecration, that the “Israelites appear to be fast wearing away their most cherished peculiarities.” Though Christians had, “for ages,” seen the Jews as “morose, narrow, unsocial and exclusive … stand[ing] aloof from what interests other people,” that characterization was fast losing steam as comity replaced friction and toleration supplanted suspicion. The “free exchange of social relations” was one way to accomplish that. Another was to attend each other’s services from time to time. A third was to celebrate and highlight the Ten Commandments, one of the few religious symbols Jews and Christians had in common. Its 10 mutually agreed-upon prescriptions made for good neighbors.

Although Christianity had long made a point of superseding the practices and values that characterized the religion from which it had first emerged, it retained the Ten Commandments, heralding them as the direct and unmediated words of God. It kept them close. In the New World, under the sway of Protestantism and its reverence for the Old Testament, it kept them closer still, so much so that this covenant with the ancient Hebrews and their descendants, which resided at the core of their way of life, was now reconfigured as a covenant with America. Once particularistic, the Ten Commandments had become nationalized.

America’s Jews did not seem to mind in the least. On the contrary: They delighted in the prominence that America bestowed on the Ten Commandments, relishing the ways in which the national narrative now accommodated the special circumstances of Jewish history. Here, after all, was something the Jews had given the nation: the ultimate gift—a foundational document.

When seen from this angle, Anshi Chesed’s anxiety over the appropriateness of its Ten Commandments window made perfect sense. An exercise in self-consciousness, of looking over its shoulder, of peering outside, the congregation’s worried response to its innovatively shaped Decalogue was not borne of interfaith dialogue or outreach; that would come later, much later. Rather, it was an expression of concern about what the neighbors would think. Although the congregation’s deliberations took place within its immediate precincts, its intended audience was as much the greater public, the readers, say, of the New-York Daily Tribune, as it was those who sat in the pews of the sanctuary, served on committees, or read The Asmonean, a paper that portrayed the Jews as “friends of true liberty, the lovers of everything that is good.” At stake was the twinned dilemma of the American Jew: How best to present Judaism as a modern faith whose tenets it shared with other inhabitants of the public square? And how, at the same time, to remain honest and true to the claims of a singular tradition? The Jews of Norfolk Street were caught in the middle. Gingerly making their way between two iterations of the Ten Commandments, one whose more traditional form highlighted its consonance with America, and another whose unusual configuration reinforced their “peculiarities,” they faced a Hobson’s choice: embracing a shared idiom or courting distinctiveness, fitting right in or standing apart.

In the end, Congregation Anshi Chesed’s congregants were not quite ready to endorse one opportunity at the expense of the other. Instead, they sought to accommodate them both, hence the two versions of the Ten Commandments. But this balancing act, this attempt at equilibrium, did not take place without a struggle. What happened on Norfolk Street in the years before the Civil War not only underscored the power of shape to stir things up but also dramatized the tensions inherent in becoming a modern American Jew, tangibly rendering them through the translucence of glass, the weightiness of stone, and the forceful presence of the Ten Commandments.

Reprinted from Set in Stone: America’s Embrace of the Ten Commandments by Jenna Weissman Joselit with permission from Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2017 by Oxford University Press.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.