When I was growing up in socialist Hungary, the word “Jew” was one of many common swear words in my lower school: stupid, idiot, Jew. For the longest time no one ever told me that such people actually existed—even among my classmates. Or that others no longer existed because they happened to be Jews—even among my own relatives.

I learned of my Jewish ancestry only once I entered adolescence, when vague murmurs of me being Jewish reached my ears from the girls in my class. One of them pointed out to me that all my friends were Jewish and, reputedly, so was my family. This was news to me, as were the words bris and circumcision. I went home and told my father right away that a girl insinuated that we were Jewish. He looked up from his crossword puzzle, lifted his reading glasses up to his forehead, and said: Hmm, there is some truth to that. With that, he placed his glasses back on the bridge of his nose and continued to work on his crossword puzzle.

My ancestors on my father’s side were Jews, almost all of whom perished in the Holocaust. As a Jewish forced laborer—one of countless unfortunate labor-service draftees who were deemed unworthy of bearing arms for the Hungarian nation yet were forced to accompany the Hungarian Second Army to the occupied territories of the Soviet Union and work under terrible conditions—my father was practically sent off to his death late in WWII along with 5,000 Hungarian Jews; he was one of only seven who came back. He subsequently lived the rest of his life ensconced in his armchair, engulfed by boundless melancholy, in and out of hospitals, hardly speaking to me during my childhood and teenage years. I didn’t realize while he was alive that he was practically a living corpse who, instead of a father figure, was just an empty vessel.

Even after I learned the truth, we never had any dinner table conversations about the horrific losses Jews endured during WWII. My father—the most affected of us all—remained defiantly quiet whenever he was confronted with my nascent curiosity about the war, or anything else for that matter. I was utterly incognizant of the existence of forced labor service. My father and his fellow comrades were captured along with the fleeing Hungarian soldiers after the Battle of Voronezh, and placed in a Russian POW camp. It was from there that he managed to escape and walk home to his hometown of Pécs only to find that his entire family had been murdered by the Hungarian and German Nazis. How much fortitude did he need to not talk about that? How much more would he have needed to actually talk about it? God only knows. But it had to have been with the greatest fortitude that he was able to survive those wartime atrocities.

Soon after I learned about my Jewish background, my father died when I was 19. His untimely death left me with a feeling of abandonment that I never fully recovered from. I poured my sorrow into uncovering the faded remains of gone worlds, most of the time encompassing only a diaphanous hope of success.

The early part of my life, for the most part, had been full of misinformation: One side of my mother’s working-class family also had Jewish ancestors, yet she set out to preserve the façade of a proper Catholic family, an effort that was met with sullen ridicule from my father who, on the other hand, offered no information about his forefathers. So I was left with an insuppressible yearning to find the missing puzzle pieces, hoping to be able to relate to my family origins, particularly to my father, whose always silent demeanor had not only been a source of annoyance for me, but also a mystery. To put all this confusion and secretiveness into context, it’s important to know that socialism itself was enshrouded in secrecy, so in some way it wasn’t unusual for families to have skeletons in their closet.

I was plagued by a desire to learn as much as I could about the history of my forefathers. Though I had been raised completely unaware that I was a Jew, somehow remains of the emotional flotsam of previous generations still lodged inside of me. The question “Who am I?” has lingered over me my whole life. I always knew the answer involved a complicity more profound than I could possibly imagine. Knowing that the long-awaited excavation of untold memories and experiences might not ameliorate my pain or help me fully understand my father’s manic inner monologue had me cursed with recurring upheavals.

There was one other survivor in my father’s family: his only older brother who, thanks to my paternal grandfather’s prescient business idea, was able to leave Hungary in 1926 when he was just a fledgling adolescent, escaping the mass murders of the Holocaust that lay ahead. For the rest of his life, blinded by wealth, my uncle famously ignored us, even during the direst times. We were his poverty-stricken relatives with whom he didn’t care to have a relationship. Our pleas were silent pleas, because we suspected that like most phone lines at the time, ours must have been bugged, too; therefore, we never actually asked for money or help getting out of Hungary. To this day, it remains a mystery what could have happened if he somehow did decide to help us—but he never did, and we were afraid to ask.

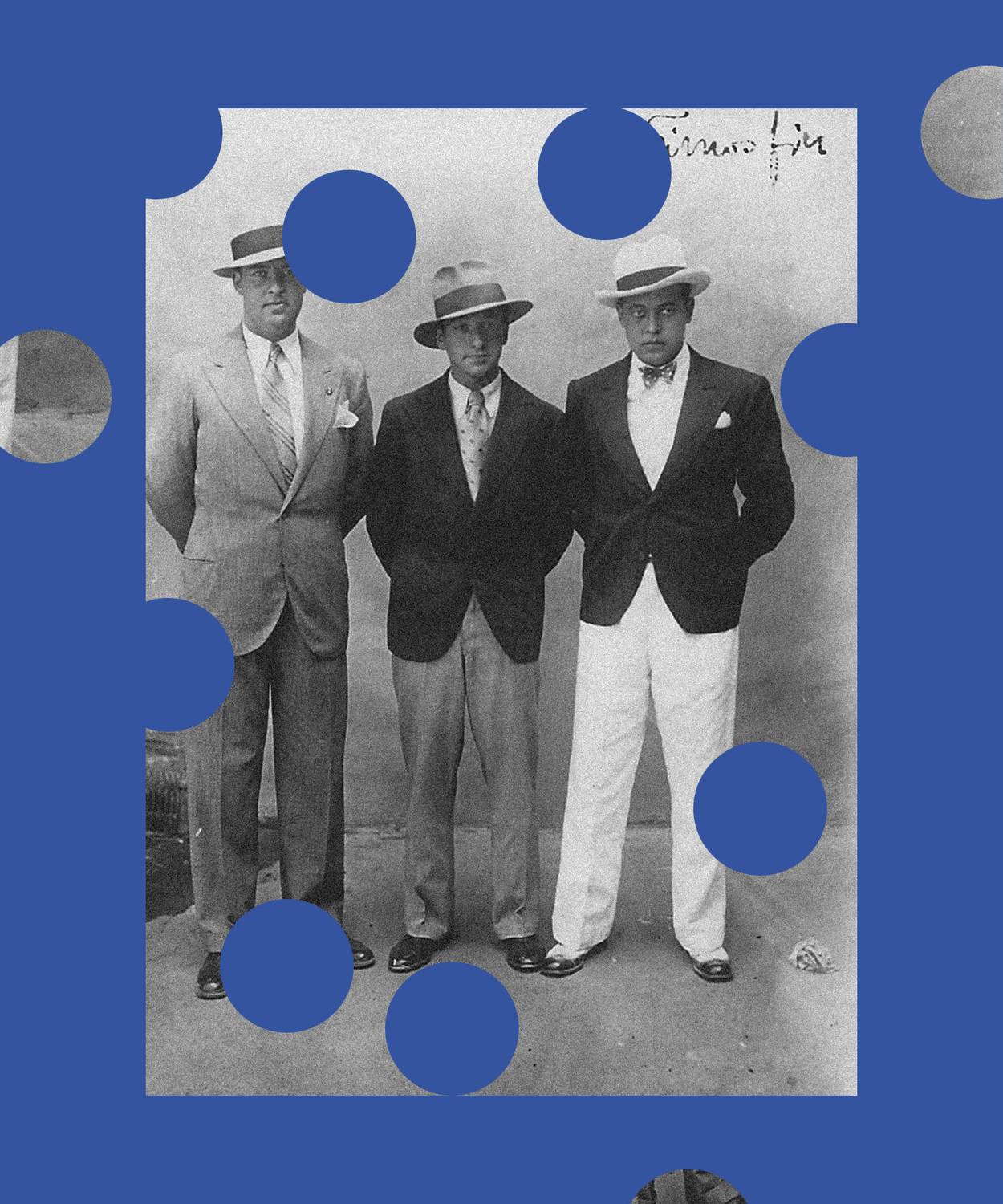

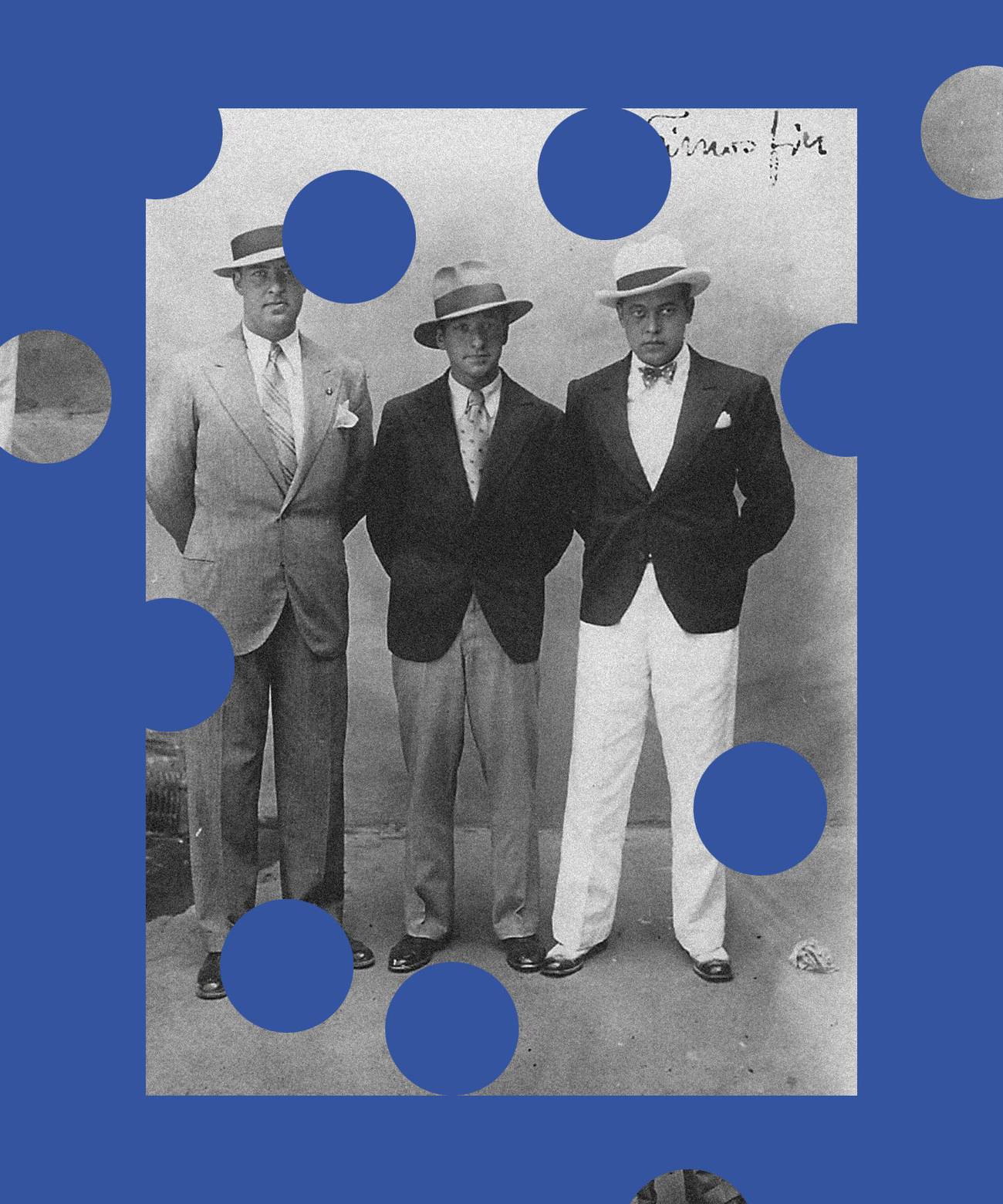

The author’s uncleCourtesy the author

As an adult, I hoped I might connect with him, and discover some of the answers I’d been seeking about my family’s history. However, many barren years went by before a compelling opportunity presented itself so that I could meet my uncle. Our meeting took place in London in the late 1970s. I was in my mid-20s, and roughly six years had passed since my father died. My father had only been able to meet up with his brother once after the war, in Vienna, and that meeting turned out to be a disaster, resulting in the end of their already rickety relationship. Regardless, I was determined to meet him—or rather, I was forced to, because my mother practically ordered me to when she found out that I was planning a trip to London, where my uncle lived. I fought her to the bitter end but, as always, I had to give in to her perseverance. Come what may, I was destined to go to my uncle’s stately apartment at 33 Knightsbridge, at the corner of Hyde Park. A trip abroad was a rarity those days, given that Hungarians could only travel abroad once every three years.

Despite the somewhat grim premise of our forthcoming meeting, I hoped to learn something that could help me better understand my father and, through him, my feelings toward him. I tried to look at the opportunity through rose-colored glasses but, at the same time, I wasn’t sure if anything beneficial could come out of meeting my uncle who bothered to call us only once a year, was known to disperse the tiniest pecuniary crumbs when he felt like it, yet never showed any openhandedness toward us. Truth be told, aside from my mother, none of us cared about his deep pockets.

When I arrived, his butler welcomed me in the foyer of the apartment, bowing deeply, and took me through two large rooms laden with expensive carpets and furniture. Our short walk ended in a longish room lined with floor-to-ceiling cherry-wood cabinets and bookshelves. The large windows opened onto the ancient trees of Hyde Park.

My uncle awaited my arrival in a rocking chair made of cherry wood. “Well, well, well, here you are!” he said, drawing out his vowels. He pointed to the couch for me to sit. “You speak English?” he asked sternly. I tried my best to answer in English, explaining that I barely did. Silence engulfed the room, the kind that usually signals the end to a list of small-talk topics that propriety requires when making acquaintance. We stared at each other with prying eyes, me with a curious look on my face, my uncle quietly unhappy. Everything on him was long: his head, his torso, his legs, his fingers, even the few strands of hair that remained on the side of his head. His eyes, on the other hand, had the appearance of two thin lines, the same shape as my father’s. I felt a wave of emotions wash over me when I noticed the resemblance.

At long last, his butler ceremoniously reentered the room, carrying a silver tray with white damask napkins and glasses of amber-colored liquor. My uncle lifted a glass and mumbled a barely audible “Cheers!” With his eyes closed, he took a small sip. Eventually he opened his eyes, and declared, “I was expecting my nephew, but my brother came to see me instead.” It took me a second to connect the dots, but I finally realized what my uncle was implying: I very much looked like my father. No kidding, Sherlock, I thought, I’m his son.

Next, my uncle bluntly asked me to fetch The Wall Street Journal for him from a nearby street vendor. I pretended to take to the task with great gusto. Upon my return, he kept turning the pages, and when he got to the last one, his eyebrows suddenly migrated to the middle of his forehead. He shot me a withering glance, and gave a roar of rage: “Hey, a section is missing!” He yelled for his butler: “Alex, telephone!”

The butler dutifully rolled in a small antique table. My uncle dialed a number and started to bicker with someone I assumed to be a secretary or an editor. I gathered from my uncle’s tone that the person on the other end of the line agreed with him. Numbers were dictated into the phone, which he repeated loudly to his butler, who then wrote them in a leather-covered notebook. He hung up, took the notebook from the butler, and studied the numbers. He closed the book with a loud thump and, as if he just happened to see me for the first time, said, “Well, okaaay then. What else?” He kept rubbing his forehead.

Not much, damn it, I would’ve liked to say, but didn’t have the nerve to do so. Once again, an awkward silence engulfed the room. Great, I thought. It took a lot of fortitude for me to pull myself together and ask my uncle what he did for a living. He sat in wordless contemplation, but finally said, “I’m already a pensioner, so I don’t have a care in the world.”

“And what did you do before you retired?”

He thought even longer than he did after the first question. I wasn’t entirely sure, but this might have been a sensitive question for him. I could sense in that Anglo-Saxon atmosphere that he wished to not delve further into his past. “There are photo albums on the shelves,” he said, changing the subject. “You can look at them, but don’t ask any questions!” He pointed his unusually long index finger in their direction. The leather covers of the five oversized albums matched not only the cherry wood in the room, but also the color of the heavy brocade drapery. I looked at a few pictures, asked no questions, and before long, I was out the door. No teary-eyed goodbyes, no affectionate hugs. He remained sealed by his stubbornness, which never dissipated enough to let his true self show, leaving me prey to the impassioned storms within me.

That just about sums up my highly anticipated visit with my uncle. He turned out to be that rara avis who continued to show no interest in me, had no answers for me, asked no questions about my father or details of his long-ago death, about my mother or my sister, and said nothing about wanting to see me again. I walked away empty-handed—figuratively and literally—which, ironically, helped me understand a few things.

In addition to feeling more detached from my uncle than ever, I realized that the challenges of sibling relationships lie in the differences two (or more) people often face, despite having come from the same parents. These challenges get even more complicated when siblings end up on different sides of the Iron Curtain in vastly disparate financial situations. Only death can erase sins, wrongdoings, and pain. Sadly, we almost always come to this realization when it’s too late—that is, after the funerals. We have no clear understanding of what the dearly departed think.

After the death of my uncle in the mid-1980s, his photo albums were delivered to me by regular mail. My uncle left a folder for his butler, aptly named “Things to Do After My Death.” One of the envelopes contained instructions to send me the albums, which contained countless photos of my uncle with celebrities, including Prince Philip, famous actors and actresses, and important political figures. I found no photos of relatives whatsoever; hence these albums did not provide me with any useful information about my missing relatives. Sadly, they turned out to be a meaningless gift despite my initial high hopes. Nowadays they are stored in a large paper box, silently preserving my uncle’s reticent past.

To this day, I still thumb through their pages occasionally and wonder why my uncle wasn’t interested in me, his only living relative. He had no wife, no children, and certainly no other relatives. Did he not feel guilty for never helping my father while he was alive? My father was his only brother who escaped the war. The reason my father kept silent about his London brother might have been out of embarrassment. This rich Englishman, his own sibling, could have saved some of their family members during the Holocaust, but he did not. I have no knowledge of anyone ever asking him for help, but based on how insouciant he was toward us, it seems unlikely that he would have helped others.

Instead of finding inner peace or answers, I had initially grown angrier with my London uncle while, at the same time, the void around me began to gradually close and inklings of sympathy toward my father sprung up within me. All the echoes of his miseries that howled inside him for years slowly dampened inside of me. I had felt my long-term confusion and abandonment being laced with a vague pleasure that promised to sustain my heavy burdens.

A pain I had wished to pluck out by the roots might not have been fully extracted, and I might never erase the sheen of a lifelong hypertrophic scar, but at least I don’t have the burden of having chosen a luxurious lifestyle over supporting less fortunate family members, or other surviving Jews. My uncle chose to remain adamant about keeping up appearances, a façade that sheltered him from the harsh reality others had to have faced. His apartment had no mezuzah attached to the doorpost, no Jewish-themed decorations at all. It looked like an aristocratic bachelor’s pad, and you couldn’t tell that a Jewish person lived there. Whether that was on purpose, I’ll never know.

His behavior made me realize that helping others, morally or financially, is an integral part of life. I consider writing a form of help, both for me as a writer and my readership—a kind of healing activity I’ll try to keep on doing for as long as I live in order to carry on the legacy of those whose voices had been silenced.

I am now an adult with limited knowledge about my family history, living in my beloved Hungary, which, sadly, seems to be moving backward instead of forward on too many levels. I have, on more than one occasion, personally encountered situations that reminded me of the famous saying: “If you ever forget you’re a Jew, a gentile will remind you.” Being acutely aware of my origins has always been important to me. But I also consider other human values of mine to be important: I am an intellectual, an author, somewhat of a global citizen who’s interested in the world and has traveled it extensively. I speak multiple languages and, thanks to them, I try to keep my finger on the global pulse. In addition to all that, I am indeed a Jew. I do my best to pay close attention to Jewish writers and their works. It pains me though that I never could learn Hebrew. For the sake of my mother, who had me baptized Catholic, I tried to connect with Catholicism, too, but that also was in vain. Overall, I feel like an outsider, a little boy who’s trying to peek into a synagogue through a door that’s been left ajar.

The harsh reality is that my father is gone. My uncle is gone. All my relatives on my father’s side whom I never knew are gone. I know that they were Jews who identified as Jewish and practiced Judaism. On the other hand, I never did, save for some sporadic moments when I thought I should, but those attempts quickly accrued to nothing. I often find myself circling back to one of my favorite Hungarian authors, Ernő Szép, when trying to explain to myself or others how I feel about my Jewish background. There is a famous section in one of his novels, Purple Acacia, which best describes my feelings, too:

Am I a Jew? How is it that I’m a Jew? Whose idea was it that I should be a Jew? It never entered my mind that I would be a Jew upon my birth. This stupid surprise awaited me in this world when I arrived. I am to be a Jew my entire life. Why? Let’s divide this up, like we do with military service or communal work, and let’s have everyone serve, let’s say, for a year, as a Jew, if someone must be a Jew in addition to being a human.