To Ukraine With Love

As the daughter of Soviet Jewish immigrants, I used to call myself ‘Russian’—but a trip to Kyiv offered me a new perspective, and a new language

It was our last day in Kyiv. Soon I would return to the life I had always known in New York before moving to Ukraine three months prior—but on that day, rather than seek respite from the smoldering heat, my partner and I were in the Jewish section of the city’s municipal cemetery, navigating a small jungle of poison ivy in a last-ditch effort to find my great-grandparents’ graves.

Two hours and many mosquito bites later, still no luck. I was ready to order a taxi and call it a day. But despite coming up empty on an earlier visit due to confusion over surnames, Vlad insisted we try the archives once more.

The archivist responded to our request gruffly, affirming what needed no affirmation—that she had better places to be. But a job is a job. She pulled down a dusty record book from the shelf and began to search, her fuchsia nails dragging down rows of names that likely hadn’t been read, much less pronounced, in decades. Then suddenly, the unexpected happened.

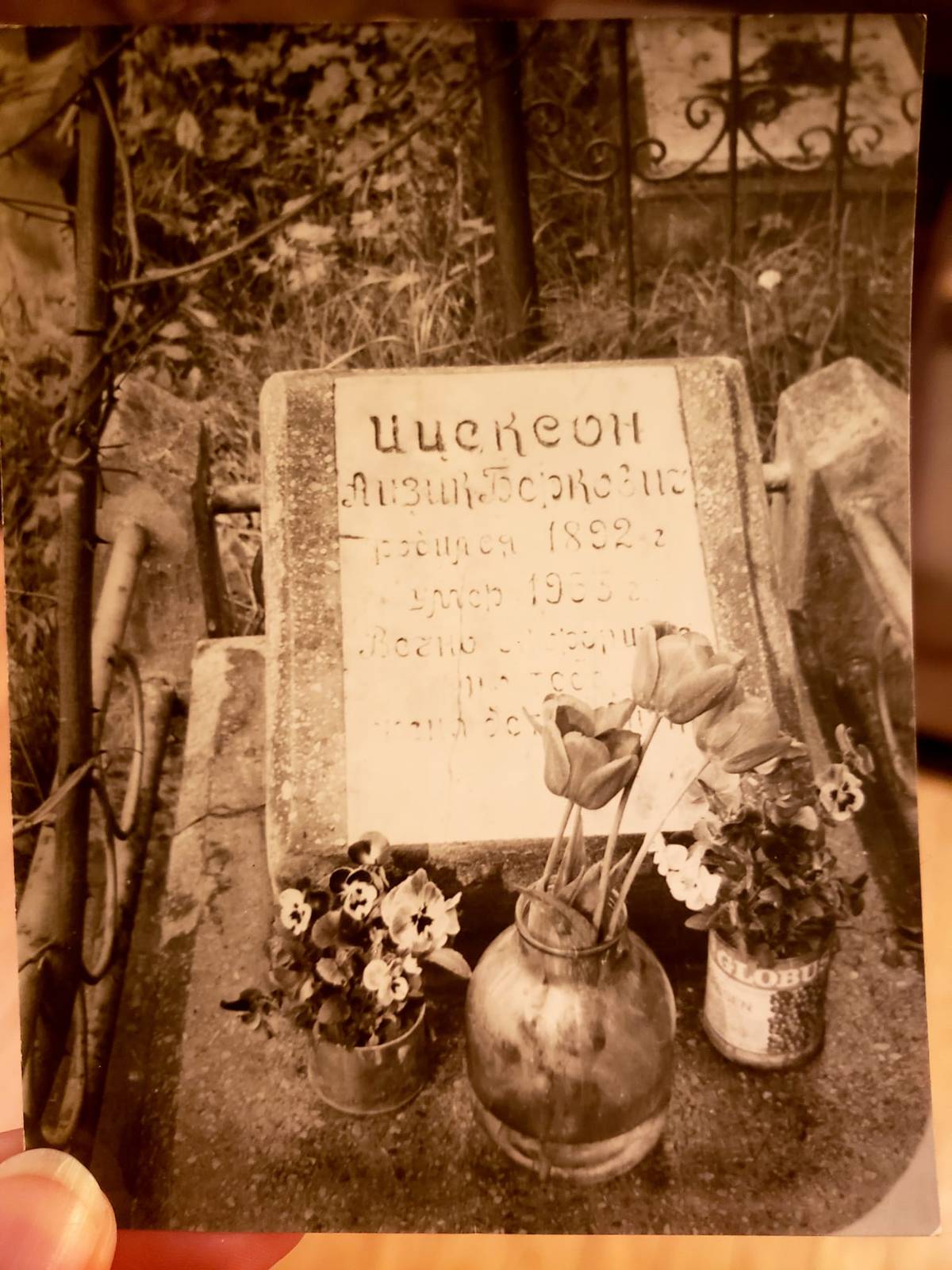

“Itsekson, Aleksandra Berkovna,” she said. “Section 12A, row 16, spot number 4. That’ll be 50 hryvnias.”

I couldn’t believe it. We found my great-grandmother.

Nowadays I refrain from blanketly referring to all Russian speakers as “Russian,” even for convenience’s sake. But all my childhood friends did it, and they called me Russian Sam.

I was born in New York and had always identified as “Russian” on the basis that we spoke Russian at home. At some point I learned that my mother’s side of the family had emigrated from Ukraine, but it was irrelevant at the time: Growing up in our Soviet immigrant enclave, the specific country origins of friends and neighbors were nothing more than basic trivia. Despite my Ukrainian roots, the Ukrainian language was entirely foreign to me; I spoke Russian, therefore I was Russian. Or at least that’s how Americans identified me.

I felt comfortable among Russian speakers and frequently sought community among them, even taking a course for Russian heritage speakers in college. From the moment my parents forbade me from spending a semester in the Old Country, I was determined to find a way to practice my Russian language skills abroad, eventually landing a job at a Kyiv-based NGO. But I did not expect to end up surrounding myself there with Ukrainian speakers, harboring doubts about speaking Russian—my heritage language—for the first time.

Of course, I couldn’t help but also turn my extended stay in my mother’s home city into something of a roots journey. My pandemic project had involved scouring genealogy sites to see how far I could get building my family tree. It turns out, not very far—my grandparents could recall their grandparents’ names, but not much else. The fact that my family renounced their Soviet citizenship before emigrating 40 years ago did not help my case: Ukrainian bureaucracy ensured that my visa would expire before I could find a way to legally prove descent from any of my distant progenitors.

I knew a few things. I knew that my grandfather’s father, Itsik, had lived on a Jewish collective farm in Crimea, and that my grandmother’s father, Hershel, died while defending Kyiv in 1941 (whether he died in action or ended up in Babyn Yar, nobody knows for sure). But any documents that could substantiate my ancestral claims had long disappeared if they ever existed. My knowledge was limited to oral history and a handful of yellowing photos, including one of Itsik’s grave with the death year inconveniently faded. And so, while turning my trip into an Everything Is Illuminated-esque tour felt admittedly self-indulgent, I nevertheless became obsessed with tracking down Itsik’s grave, if only to serve as material proof of my family origins.

Before our departure, my aunt warned Vlad and me to avoid speaking Russian in Kyiv lest we attract unwanted attention from Banderite-nationalists. (I don’t have a single living relative left in Ukraine, so news often gets filtered through the Russian propaganda machine before reaching some of my family members here.) Contrary to what she may have heard, you can get by in most big cities on Russian and English alone—but I enrolled in Ukrainian lessons anyway, both to smooth my transition and out of genuine interest.

While Russian remains the lingua franca of most former Soviet states, the movement to assert Ukrainian as the country’s official language has gained momentum in recent years. Today, Ukrainian is not only the official language; it is the preferred language of young progressives, including many Russophones who made a categorical switch to speaking Ukrainian after the Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014 and ongoing war in Donbas. And so, it stands to reason that most of the people I wanted to get to know—young artists, musicians, intellectuals—were Ukrainian speakers. Sure, most Kyivites understand Russian and plenty carry out their lives entirely in Russian. But I became uncomfortably hyperaware whenever anyone—particularly anyone within our newfound friend group—would code-switch to accommodate me.

Never mind the social pressure. Speaking Ukrainian, even when bungled, was genuinely fun. It felt lighter and brighter than Russian. It also shares a lot with Yiddish, my would-be heritage language: a history of suppression, a vibrant revival culture, and perennial ridicule from a certain class of Russophone, or sovok—the derisive term for post-Soviet persons with pro-Soviet mentality. While “Russian” had been a catchall for any Russian speakers in my immigrant community growing up, I hadn’t identified that way in years. When pressed about my origins in Kyiv, I would coolly respond “Moya mama Kyivlyanka”—my mom is a Kyivite—and the rest could be inferred.

Whether I could personally stake a claim to Ukrainian identity remained a complicated question. No one in my family had ever lived in the independent state of Ukraine; when they left, it was still part of the Soviet Union. That my family had lived on Ukrainian soil for generations was an inconvenient, and ultimately irrelevant, truth. Ethnically, I’m not the least bit Ukrainian or even Slavic. Historically, local authorities, first imperial Russian and later Soviet, had not been kind to my ancestors. Religiously—well, it goes without saying. So how could I reclaim any semblance of Ukrainian identity if it had never been claimed in the first place? Why should I bother?

Compounding the perplexity of these questions was the yet-unsolved riddle of Itsik’s grave. We first arrived at the municipal cemetery on a foggy April morning, with only the photograph and a few hazy details to guide our search. I knew that Itsik and his wife, my great-grandmother Batsheva, were buried there separately, but their death years were uncertain. When I explained this to the archivist, she looked at me with exasperation: “1955 is impossible. This cemetery was founded in 1957. Are you sure you’re in the right place?”

“That’s the only information I have. And this,” I said, handing her my phone. She looked at the photo of Itsik’s grave and zoomed in on the faded death year, squinting her eyes in the same manner of all people we showed it to. The beguiling last two digits looked like 53, 55, 63, or 65. The longer you stared at them, the more they appeared to transform.

After 10 minutes of searching, she gave up. “I’m sorry, there is nothing. Is there another name you want to try?”

“Yes, Kaprova,” I said, mistakenly giving her my great-grandmother’s maiden name. It was an honest mistake: My grandfather had changed his surname to his mother’s to sound less obviously Jewish. I had known him as Boris Kaprov, but he was born Berko Itsekson. Still, the archives revealed nothing.

When we returned to the cemetery two months later, I had learned that it had not been uncommon for grave plots to be sold if no living relatives were around to claim them. If my family left in the 1970s, who knows what could have happened since? Moreover, if the cemetery was founded in 1957, when had Itsik died? Some things just didn’t add up.

But it wasn’t a total loss. When we went back searching for great-grandmother Itsekson—not Kaprova—her name turned up in the archives as plain as day. I learned then that she had legally changed her first name from Batsheva to Aleksandra, likely Russifying it for the same reasons my grandfather did his.

A cemetery worker led us to her grave, and the moment I saw it, I knew we were in the right place: The photo embedded in the headstone resembled the face I had seen in our family photos. We cleaned the grave as best we could and left a pebble on the headstone for each of Batsheva’s descendants.

The discovery was a fitting end to our stay, both bittersweet and open-ended. I still don’t know where Itsik is buried, or what happened to my great-grandfather Hershel who died during the war. I feel solidarity with Ukrainians whose language and culture were suppressed under Soviet rule and flattened by Russification. Now that I’m back in New York, my ears immediately perk up to the sound of Ukrainian. Even my mother and aunt have started quizzing me on simple phrases and correcting my pronunciation. Maybe I can convince them to visit with me someday.

As for my Ukrainian identity, I wish I could say the trip helped solidify it, but I think it only served to complicate it further. “First-generation American of Ukrainian Jewish extraction” doesn’t quite roll off the tongue, but I’ll take it over Russian Sam.

Samantha Shokin is a writer and musician based in Brooklyn.