In Tribute to an Educator

Campus Week: A remembrance for the longtime head of Yeshiva University, Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm

Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm, the longtime head of Yeshiva University, died earlier this year. He was a rabbi of incredible erudition, a theologian of great perception, an educational leader of remarkable accomplishment, and a uniquely warm and sensitive husband, father, uncle, grandfather and great-grandfather. Or so I’ve heard.

I didn’t really know him. He lived in Manhattan. I live in Pittsburgh.

Within the relatively small American Orthodox community, Dr. Lamm and I were at most within one or two degrees of separation, but we didn’t really have opportunities to interact. Yes, I went to Yeshiva University. But unlike all my siblings, my children, and their spouses, I dropped out. (Don’t try this at home kids; getting into law school, sitting for the bar, and becoming a judge without a college degree is unlikely in this modern age.) I have read some of his books, and sampled some of his lectures online. But we certainly didn’t invite each other to family functions. And, given my limited means and distance from Manhattan, there would be no reason for him to endeavor to cultivate a relationship with me.

So we didn’t really know each other. But there were those few times ...

Our son Mikey was born with cystic fibrosis. That meant 70 plus medications a day, oxygen tanks, and spending literally half his life in the hospital. In high school, Mikey had one dream—he wanted to spend one term at Yeshiva University in New York.

Given Mikey’s medical condition, his dream seemed unlikely. But he applied to college at YU anyway. It was his first-choice school. It was his second-choice school. It was his safety school. It was the only school he applied to. And he was accepted.

Mikey showed up as a freshman at YU with his oxygen tank, his vicious cough, and a pharmacy’s-worth of medicines. He never expected to be able to spend four years there, but by the end of his first week it became obvious that even one term was unrealistic. They sent him home to Pittsburgh, and he went straight into the hospital.

I called the university and asked if it was conceivable for someone who could only be there half the time to eventually graduate from Yeshiva University. The person on the phone went on about academic standards committees and the Middle States Association, which apparently had something to do with college accreditation. But, she said, I will inquire.

Two weeks later and out of the hospital, Mikey returned to YU to collect his things, his dream shattered. There was a note on his dorm room door that read “See the Dean,” so when he was done packing, he went to the dean’s office. The dean looked across his desk at the skinny kid with blue fingernails (not enough oxygen) and said: “Young man, you are going to graduate from Yeshiva University. Whatever it takes, we will get you through.” He then proceeded to make arrangements to accommodate an excellent student who would, on average, over the next four years, alternate three weeks in school and three weeks hospitalized back in Pittsburgh.

Around Thanksgiving time, at a wedding in Memphis, I met the president of Yeshiva University, Rabbi Norman Lamm. YU has thousands of students, so I was pretty surprised that when he heard my name, he asked me if I was related to Mikey. He knew the whole story. When I endeavored to stammer out thanks for the school’s remarkable efforts on Mikey’s behalf, he looked at me with a puzzled expression. “But that’s who we are,” said the world-renowned rabbi, theologian, and philosopher about his university, which was then rated among the top 50 national universities by U.S. News & World Report.

At the end of his fourth year (as his health declined, Mikey took on a lighter schedule), Mikey was elected student body vice president. He didn’t think it would be fair to run for president, since he was only there half the time. He just needed to finish that last term.

Mikey loved Yeshiva, and he really didn’t want to leave. But before the term ended, Mikey hit a respiratory wall. Back in the ICU in Pittsburgh it became clear that he needed new lungs. With Rabbi Lamm’s blessing, YU chartered a bus and offered the student body an 800-mile, Sunday round trip to visit Mikey. The university even provided sandwiches. That visit was better than the best drugs.

I called the university to discuss the financial implications of Mikey missing the last weeks of the term, with little likelihood that he would be back that year, if ever. The person I talked to simply said, “I will inquire.”

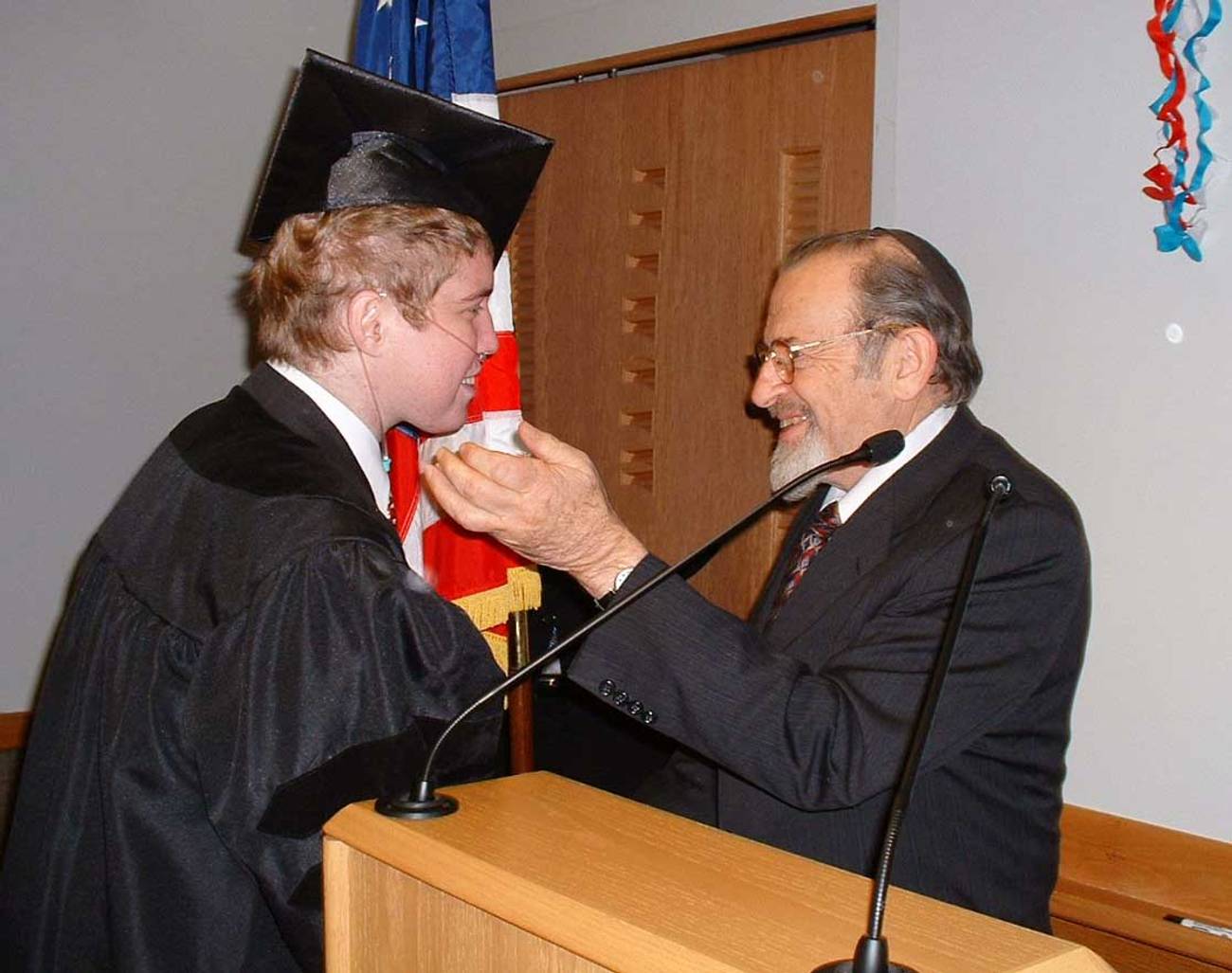

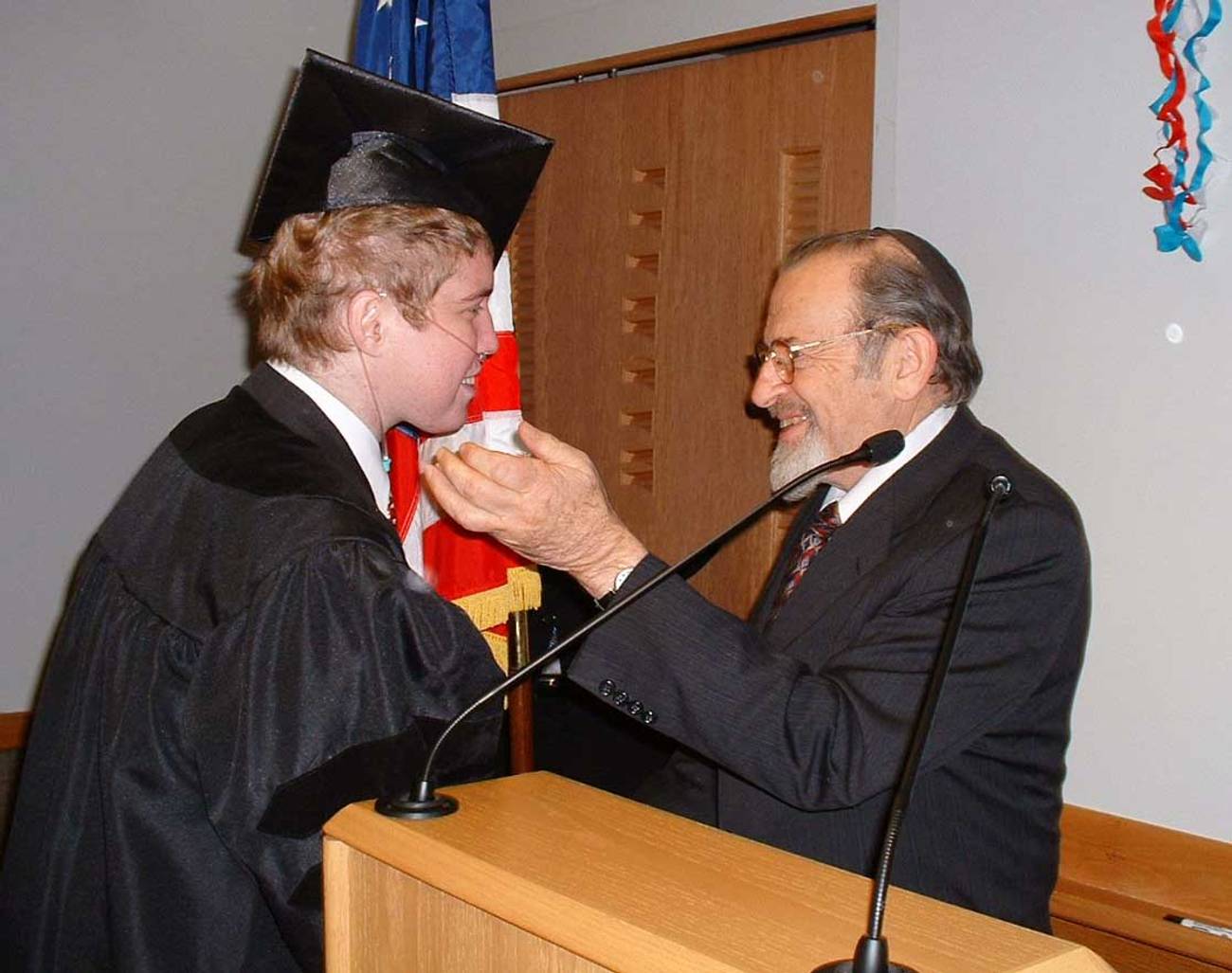

About a week later, Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm flew to Pittsburgh, and, in the executive offices of the Greater Pittsburgh International Airport, before a hastily gathered group of friends and family, awarded Mikey Butler—who came by ambulance from the ICU—a diploma from Yeshiva University. I will never forget watching that great man unfold himself from the airport tram which, driven by a county policeman, had brought him from the gate. For just a moment he paused, taking in his surroundings. He stood there, seeming so tall, one of the great teachers—by example—of a divinely inspired Masoretic tradition that distilled down to flying to Pittsburgh to award a piece of paper to a kid who, for 4 1/2 years, never stopped trying.

A couple months later, when it seemed that time was about to run out, Mikey got a double lung transplant. That winter, Yeshiva University’s Student Council changed its constitution so that even though he had technically graduated, Mikey Butler could continue as vice president of the student body until the end of the year. Mikey returned in June to graduate again with his class at Madison Square Garden. When his name was called, Rabbi Lamm handed Mikey his diploma and hugged him. And together they got a standing ovation.

A few months later Mikey got post-transplant lymphoma from his new lungs. He went through three rounds of chemo, radiation, and stem cell transplants, all to no avail. On the day of his funeral, despite the snow, there were several busloads of students from Yeshiva University, as well as a delegation of students who flew in with Yeshiva’s new president at the time, Richard Joel. At Rabbi Lamm’s behest, Yeshiva cut short its Torah classes that morning, and what seemed like the entire student body gathered in the university’s main auditorium for a video hookup to Mikey’s funeral. In those pre-Zoom days of 2004, they couldn’t get it to work. But they held their own memorial service anyway. And of course Rabbi Lamm led it off, giving a great eulogy for our son.

In Jewish tradition, when you encounter royalty, even the president of the United States, there is a special blessing for the occasion that acknowledges that God has broken off a little piece of the honor due Him and bestowed it upon a human being. In his tribute to Mikey, it seemed that Rabbi Lamm had broken off a piece of his own honor and bestowed it upon a kid from Pittsburgh who tried very, very hard.

But there’s more. During the traditional shiva, Rabbi Lamm flew back to Pittsburgh to pay his respects and personally deliver a video of YU’s memorial service so that we wouldn’t miss what he and the other speakers had to say about our son.

My family is of modest means. We are not intellectuals. I dropped out of YU. But Rabbi Lamm honored my son and set an example for the institution that he led of what it meant to be a leader and scholar. Jewish legend has it that God picked the shepherd Moses to lead the Jews after an incident in which he demonstrated his compassion and sensitivity by rescuing a lost lamb (that’s with a B) and carrying it back to the flock. It was just one little lamb. But Moses went to all that trouble anyway. Apparently, God perceived that not merely as leadership, but as greatness.

Rabbi Lamm and I crossed paths a few times, and I was inspired for a lifetime. He was an educator who left us all an extraordinary example to follow.

Dan Butler is a judge in Pittsburgh. He lives with his wife, Nina, and their family in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood.