Uncle Manuel and Me

Finding my own path in the family story

My great-uncle Manuel was a family mystery. The Rosenberg clan, based in Cincinnati, was all about business—real estate, mainly. But Manuel, born in New Orleans in 1897 to Russian immigrants from Kyiv and Minsk, followed a different path. “Uncle Manuel was an artist,” my father would say, in order to explain his uncle’s globe-trotting, bon vivant life in the Roaring ’20s, hobnobbing with stage and screen stars of the day, while making a decent living as a journalist, illustrator, and publisher. Uncle Manuel was a bit misunderstood because the working-class Rosenbergs could not understand his cultured lifestyle—yet he was adored as the family celebrity. Everyone eagerly awaited each rare visit.

Like my great-uncle, I, too, was bent on following a different path despite my family’s best efforts to steer me toward a business career. Majoring in welding metal sculptures at the San Francisco Art Institute, working toward my MFA at New York University Graduate Film School, and eventually directing films in Hollywood. But all the while, the thought gnawed at me: Was I living a pretend life, waiting for my real life to begin? I knew deep down that my parents were hoping I would come to my senses, get married, raise children, and live in that white-picket-fence suburban house. Isn’t that what a nice Jewish girl is supposed to do?

So, it was both oddly exciting and equally confounding when my dad’s brother, Uncle Alan Rosenberg, would say to me, “You are most like your Uncle Manuel.”

Because Uncle Manuel had died in 1967, when I was 10, I had no clue what that meant, until one ominous morning in October 2016 in New York City, crossing the Morningside Heights streets slick with rain. The plan was to view my uncle’s artwork, which I’d heard was stored in the Rare Archive Library at Columbia University—take a quick peek, and then head off to lunch. I had no idea I would spend the next week immersed in boxes of Manuel Rosenberg’s sketches, newspaper clippings, and article notes, drawn each day to the library from opening to closing, learning the history of my great-uncle’s artistic path, 100 years ago. That was when the story of Uncle Manuel and me really began.

The Rare Archive Library was eerily quiet. In the 43 years since my uncle’s work was donated to Columbia by his wife, Lydie Rosenberg, I was the first person to check out the box. Multiple boxes, really. Gray cardboard boxes filled with magical treasures collected over a lifetime.

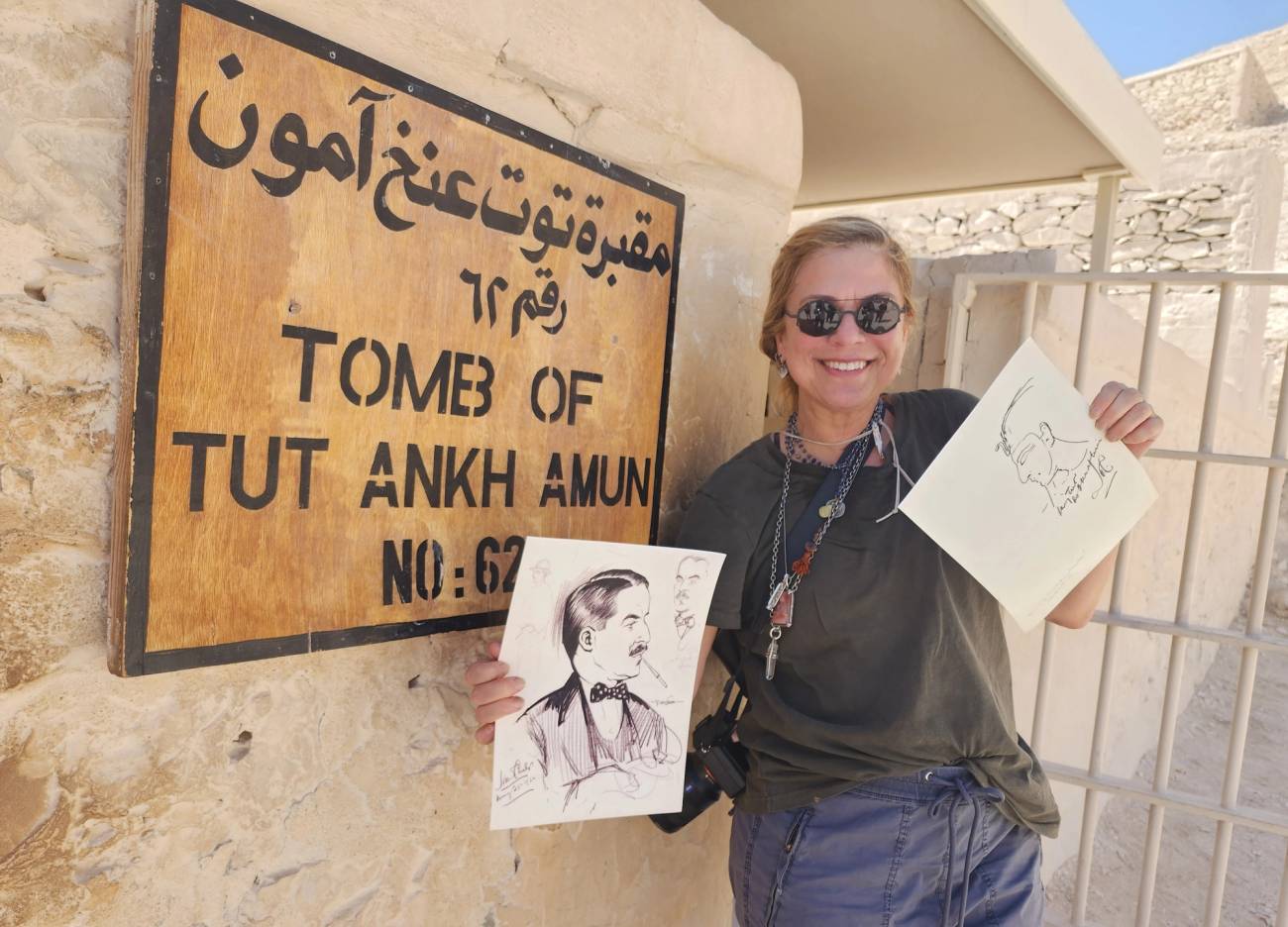

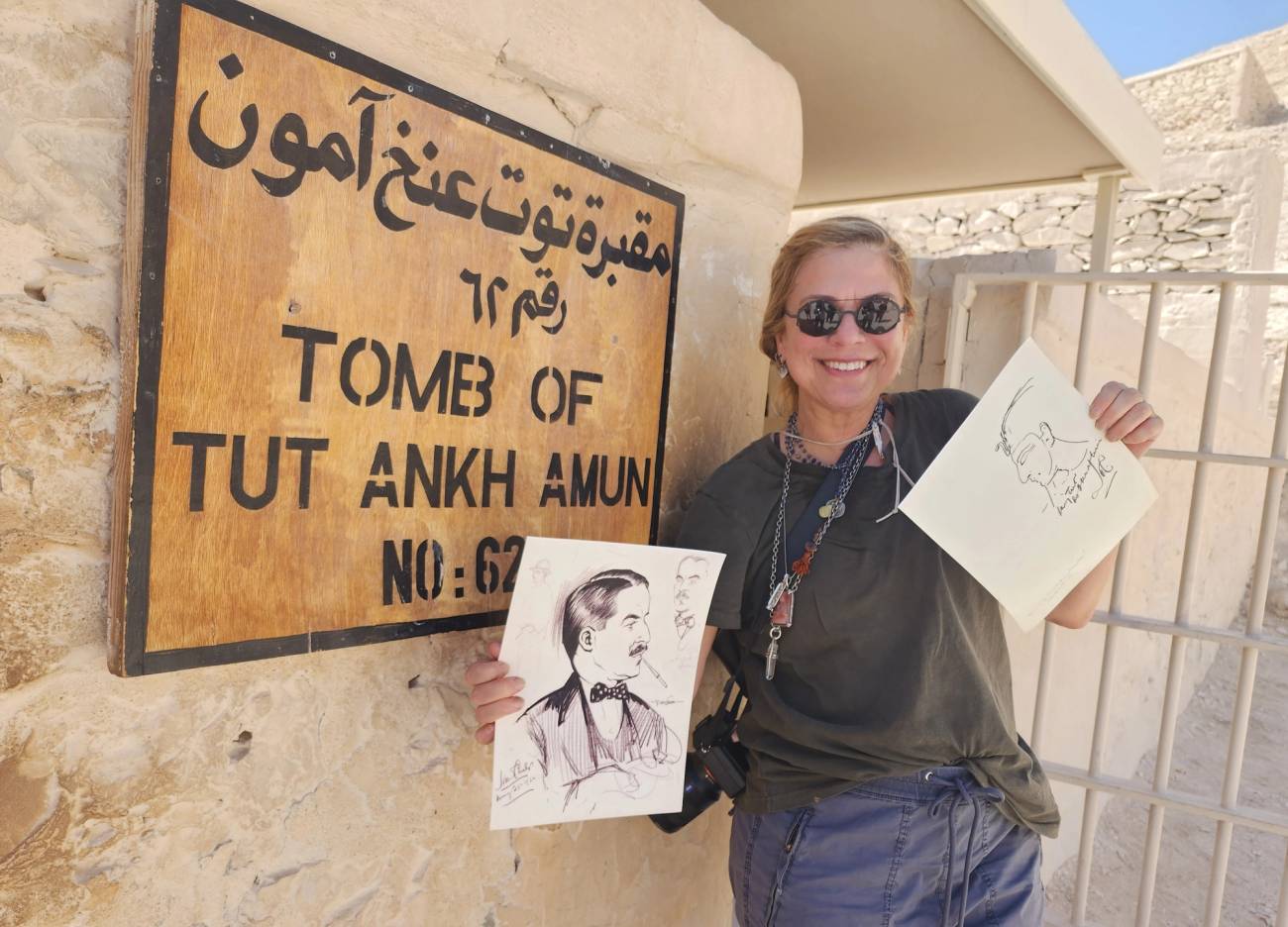

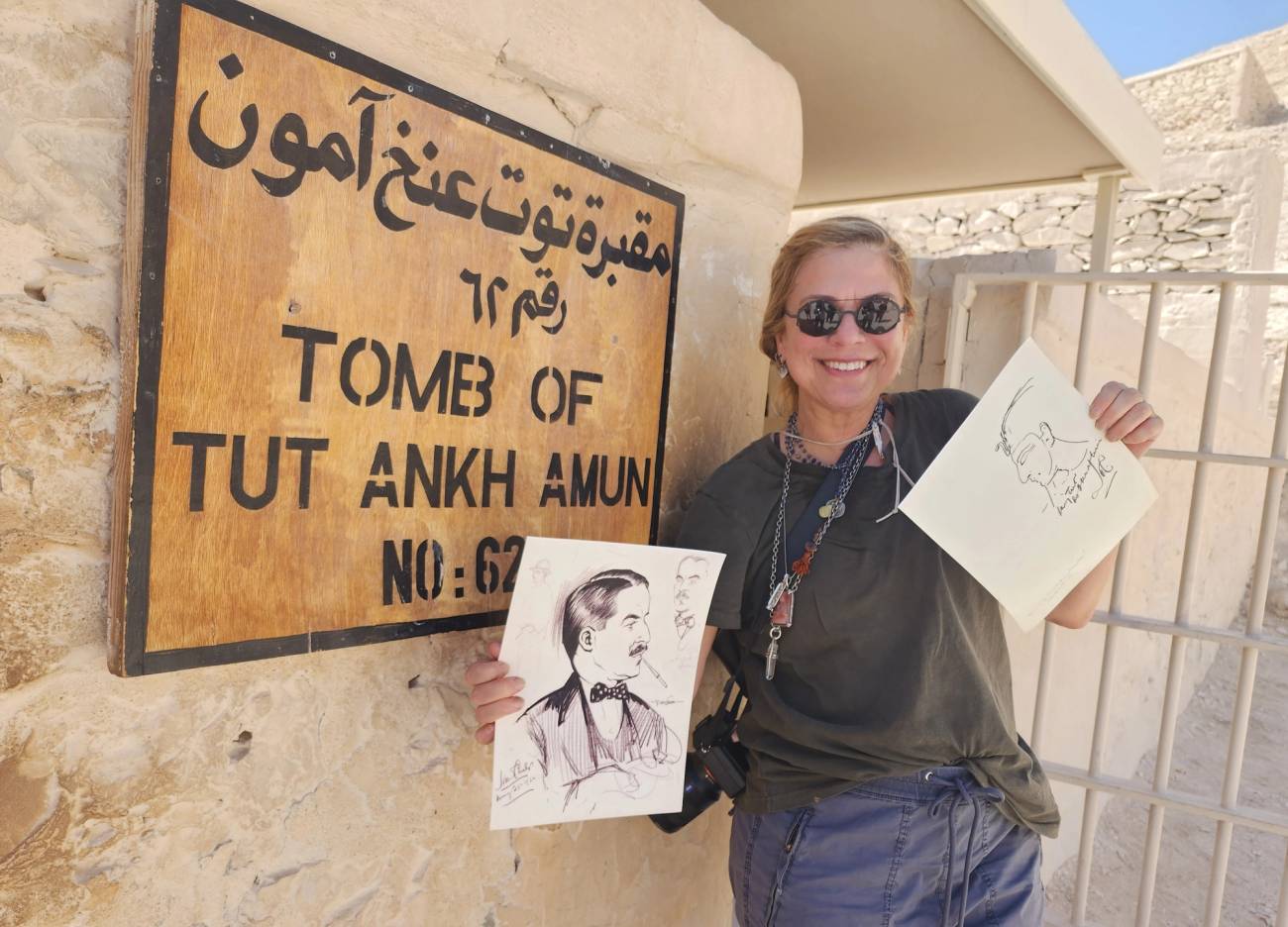

More than 300 sketches and caricatures of leading personalities in public life and the arts included escape artist Harry Houdini; British Egyptologist Howard Carter, who discovered King Tut’s tomb; comedian Groucho Marx; pianist Liberace; and actress Debbie Reynolds, along with numerous other entertainers, sportsmen, politicians, and writers. Most notable were his travel drawings made between the 1920s and the ’50s—including 60 sheets of drawings made during his trip to Russia in the company of other Western journalists in 1929.

As I opened the lid on the first box and touched the pencil sketch on top, I got zapped. It was as if an invisible current of energy connected me directly to Uncle Manuel. To the people he met and the places he went.

My cousin surprised me recently with a letter from Manuel that she found in a box of her family’s papers. In the neatly typed correspondence, he explained how he came to pursue a life in the arts.

The year was 1911. Manuel Rosenberg was 14 and visiting his mother’s family in the Bronx. Standing at the rail of a ferry boat, his eyes were agog and his mouth open as his heart beat like a trip hammer. New York! There was the Statue of Liberty. There was the great skyline. He described the buildings as “white crags”: “Somewhere behind these tall buildings, success was waiting; waiting to waylay that overgrown, self-confident kid. That kid was me.”

That was when things started to happen for him, he continued: “An artist has to eat and the first thing that happened to me was hunger. That meant I had to go places and get a job. My first assignment was a cartoon for a foreign newspaper’s front page.” That paper was the London Herald in 1915 at the age of 18.

Like me, Manuel wondered how he became fascinated with art and travel. He questioned whether he was dropped on his head when young or born with a pencil in his hand as an impediment. He says that his family couldn’t account for it. Nothing like this had ever happened to them before. They tried everything in their power to turn him from his “ruinous” course. “An artist? A businessman, a scholar, a rabbi even, but an artist—never!”

Growing up in the Over-the-Rhine immigrant neighborhood of Cincinnati, Manuel sold papers (later he would help produce issues of the Cincinnati Post as their art editor). With that hard-earned money, he attended the Cincinnati Art Academy. A local real estate operator named Walter S. Coles “discovered” him and his talent and sent him to the National Academy of Design in New York City, the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, and later to study in Paris. In 1917, the Salt Lake City Telegram wrote, “Although only 21 years old, his accomplishments are much as to cause the envy of many another cartoonist of many more years of life and experience, and those in position to be regarded as authorities on the subject predict an even more brilliant future for him.” In fact, he did have a stellar career as a noted illustrator, cartoonist, and writer who was the chief artist for the Scripps-Howard chain of newspapers for 13 years. His four books on newspaper art and drawing were used in colleges. In 1928, he was involved in a second career as the founder and publisher of The Advertiser and Markets of America—well-known monthly publications devoted to interests in national advertising in the U.S. and Canada.

Even though I was young when Uncle Manuel passed away from cancer, I remember him well. He was a big bear of a man—over 6 feet tall—with brown wavy hair, wire-rimmed glasses, and a gentle smile. Manuel looked a lot like his younger brother, my Grandpa Simon, and I would often get them confused.

The only photo I have of Uncle Manuel and me together is from my first birthday in 1958 when he visited Cincinnati from his home in New York City. Today, more than a half-century later, I wonder what he would have thought if he knew that the child pictured with him in diaper and ponytail would one day discover, and admire, his body of work at the Rare Archive Library? Would he be surprised to learn that my artistic journey mirrored his in many ways? We both had extensive art educations, exhibited at museums, documented our celebrity friendships (his with autographed sketches in articles, and mine with photographs in a series called Movie Star and Famous People Picture Books), and shared images and stories of our travels abroad (his series was called Sketches and Notes by a Post Artist, and I created a travel card deck called Travels with the Single Girl.) Perhaps the prejudices he encountered as a Jewish man living in early-20th-century America were not unlike the challenges faced by a girl from the Midwest attempting to make it as a director in Hollywood when women faced so many barriers.

There are many voices in every family. When you reach back to elders who are living or even those who have passed on—you can find inspiration and guidance. Every family has someone most like you. This person might skip a generation or two but when you discover who they are and the extraordinary life they led—it gives you comfort that you are not alone.

As I travel through life, Uncle Manuel pops up in the most unexpected places. Like when I walk out my door at the corner of Hollywood and Vine and step over the Walk of Fame stars he sketched and interviewed like silent film star Theda Bara or Cisco Kid’s Leo Carrillo I can’t help but smile knowing he is with me in spirit. When I compare his 1926 drawing of the Ponte Vecchio in Florence with my photograph from the same vantage point in 2008, I am filled with a sense of kismet. His windmill sketch in Sans Souci, Germany, from 1922 side by side with my Sans Souci windmill shot in 2014 shows me that he has guided me to follow in his footsteps for many years.

Living the life of an artist is challenging. It is an unconventional path that can be greatly misunderstood. Knowing I’m not the only one who struggled against what society calls “the norm” and that “I am living my real life” has brought me newfound confidence and clarity. Uncle Manuel was much more than what my father said, “just an artist.” Now that I understand how much I actually am like him, I realize that living a life in the arts is my true path and it’s respectable and it’s enough—something I did not understand before.

Anita Rosenberg is a writer, photographer, and Cosmic Coach of Chinese Metaphysics living and working at the iconic corner of Hollywood and Vine. She is currently developing a project about her beloved great-uncle titled Uncle Manuel and Me.