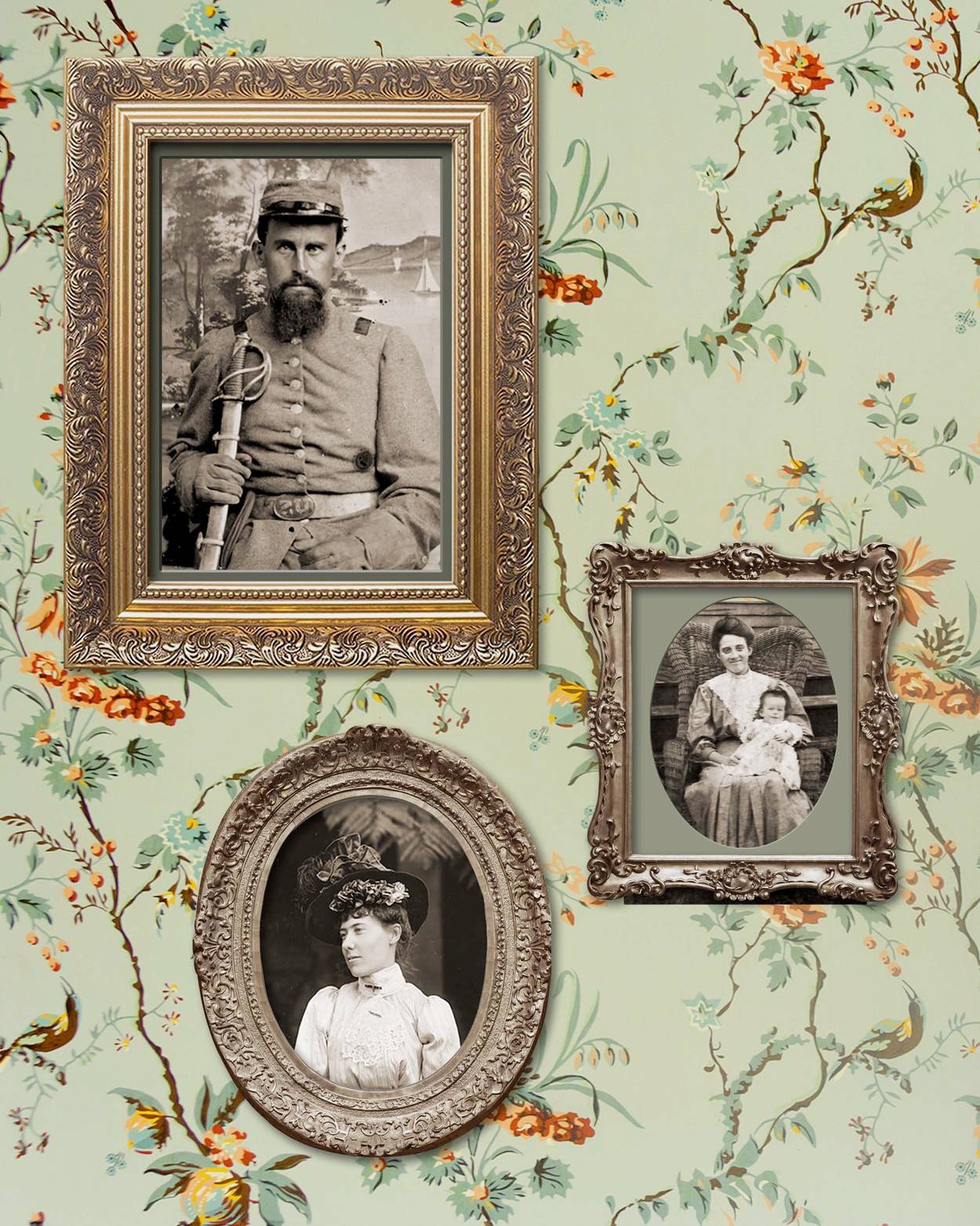

Uncovering My Confederate Roots

Learning the truth about my great-great-grandfather made me commit to writing about African American history and battling racism

My grandmother told me two things about her grandfather Aaron Katz: He moved south to fight for the Confederacy because he thought the South would win the Civil War, and—much to her chagrin—he would be the only veteran wearing gray rather than blue on Decoration Day in her hometown of Bellefonte, Pennsylvania.

Neither of these things, it turns out, is true. But my great-great-grandfather was, indeed, a Confederate soldier.

Knowing that I am a Jew descended from a Confederate soldier used to strike me as novel and unexpected, something that I could use to trip people up in games of Two Truths and a Lie. It was how I might feel if one of my great-great-grandparents had been a vaudeville performer or a lab assistant to Thomas Edison. Gaining a deeper understanding of American history, however, has erased this blithe, flippant view of my forebear.

In 2005, the school district of Philadelphia mandated a yearlong course in African American history as a requirement for high school graduation. I volunteered to be one of the first social studies educators to teach the new course and continued to do so for eight years. That experience transformed my understanding of both American history and our country in the present day. And it made me contemplate my direct connection to America’s peculiar institution.

Before teaching the course, I confess to having what is probably a typical Yankee perspective. Slavery, lynching, Jim Crow, and voter suppression were part of Southern history; the North, by contrast, was the home of abolitionism, the Underground Railroad, the Harlem Renaissance, and the destination of Black Americans during the Great Migration. As a Northerner, a Jew, a liberal, and a resident of a racially mixed neighborhood, I had always tried to separate myself from our country’s entrenched racism. My self-justifications, though, were doomed to failure. It would be impossible to spend a year studying American history through the lens of race without concluding that systemic, institutional racism and white supremacy are deep-rooted and persistent features of our national story—North and South alike.

The African American history class emphasized local history, and I was quickly disabused of the myth of stark sectional difference. Slavery was common in 17th- and early-18th-century Philadelphia. In 1838, Pennsylvania Hall, built as an abolitionist meeting place, was burned to the ground by a white mob three days after it opened. Most Philadelphia residents at the time were supportive or neutral on the question of slavery; abolitionists were few in number and viewed as radicals. Though Black people fleeing the South flocked to Philadelphia in the early 20th century, the city was nicknamed “Up South” because of the racism encountered by migrants. Teaching the course changed how I viewed my hometown.

It also changed how I viewed my Confederate ancestor. No longer was my great-great-grandfather just a nifty talking point. Aaron Katz had enlisted and fought to defend a slave state. I didn’t find his story amusing anymore; it was deeply upsetting.

When I left the classroom eight years ago to pursue other history-related projects, I promised myself that I would try to learn about my Confederate great-great-grandfather. Perhaps afraid of what I might learn, and certainly afraid I might find nothing, I put off this project until the pandemic and a newly empty nest gave me ample time to dive in.

Aaron Katz was born in Philadelphia in 1844. Census records indicate that in 1860, he was a clerk residing in Charlotte, North Carolina. Thus, my grandmother’s story that he moved south to fight for what he expected to be the winning side of the Civil War was false.

The handful of scholars who have researched Jewish Confederate soldiers indicate that they enlisted for a variety of reasons: a sense of duty, a thirst for adventure, a desire to prove their manhood, an opportunity to demonstrate their worthiness as loyal citizens, and to contradict the stereotype of Jews as cowardly, bookish, and disloyal. The South—where race and class seem to have mattered more than religion in terms of determining social status—was generally welcoming to Jews.

Most Jewish Confederate soldiers were peddlers, artisans, tailors, shopkeepers, or clerks in a dry goods store—like Aaron Katz. Few had ever visited a plantation, much less owned a slave. Like his Jewish counterparts throughout the South, Katz enlisted in the town where he lived and did so along with other young, Jewish men. In total, about 2,000 Jews fought for the Confederacy, though this is an estimate, as religion was not indicated on military records.

The best primary source about the experience of Jewish Confederate soldiers is Louis Leon’s The Diary of a Tar Heel Confederate Soldier. A stroke of luck for me as a researcher, Aaron Katz was his close friend and comrade in arms. Leon’s wartime diary recounts lots of high times early in the conflict. He and Katz regularly slipped away from their encampment to enjoy the company of ladies and the pleasures of drink. From his diary entry for May 17, 1863, written in Petersburg, Virginia: “Katz and myself went uptown—ate two suppers. Had a very good time while in town.”

The tone of the diary shifts, however, when the brigade suffers significant losses at the Battle of Gettysburg. Katz, who had been promoted to sergeant major, was wounded on the second day of the conflict and taken prisoner by Union forces. At some point after his capture, Katz swore allegiance to the United States and never rejoined his former unit.

In the years after the Civil War, Aaron Katz experienced a business failure in Wichita, Kansas, and then settled in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, where he opened a women’s clothing store that stayed in the family for three generations. His frontpage obituary in the town’s Centre Democrat describes him as “a shrewd business man who had held a leading place as a Bellefonte merchant and citizen.” According to the obituary, he was an honorary member of the Grand Army of the Republic in his adopted hometown. My grandmother’s memory of him strutting about in a gray uniform must have been a figment of her imagination.

After teaching the African American history class, and continuing to write and speak about Black history, it is clear to me that the existence of Sergeant Major Aaron Katz is much more than a fun fact about my family tree. Having a Confederate ancestor makes me feel definitively tied to our nation’s deep-rooted racism.

Indian novelist Anjali Enjeti stated in a recent interview on NPR, “Our ancestors’ pasts really shape our identities. They shape our views of the world. They shape our understanding of ourselves. And we are lost without them. They are our foundation. And if we don’t have this knowledge of our histories, of our ancestors, of what they endured, it’s really hard to understand our own self-concept.”

Although Enjeti is referring specifically to the traumas experienced during the 1947 Partition of India, as Jews we are well accustomed to the idea that our ancestors have suffered. I am filled with gratitude for my paternal great-grandfather Saul Kaplan, who came to America on his own from Russia in 1901 at age 13. He worked in a broom factory that damaged his hands and a button factory that filled his lungs with toxic dust. I can draw a direct line from his sacrifices to my comfort and affluence.

It is a more disconcerting experience to contemplate the trajectory of my Philadelphia-born maternal great-great-grandfather Aaron Katz, who willingly left the City of Brotherly Love to seek his fortune in the slave-owning South.

My work as a historian continually reminds me how recent the Civil War actually was. In my case, it is the span of four generations. I have long owned a photo of a teenaged Aaron Katz in Confederate uniform. Recently, a cousin who is downsizing offered to give me a stool that sat in Katz’s store from the day it opened. I eagerly accepted. Not because I need more furniture; it doesn’t even fit with the décor of my house. I wanted it as a tangible reminder that I have an explicit connection to our nation’s racist roots and the responsibility to work for social justice. In the spirit of tikkun olam, my great-great-grandfather’s story clarifies for me that I must play an active role in trying to rectify the wrongs of slavery and its enduring legacy.

Reckoning with the past, I believe, is essential to moving forward toward a just society. As time goes on, I feel an ever-deepening commitment to research, to teach, and to write about African American history.

I hope one day my own great-great-grandchildren will be proud of my effort.

Amy Cohen is a writer, historian, and Director of Education for History Making Productions, a documentary film company.