Visiting Hours

After surviving the Hamas massacre, a Thai agricultural worker with severe burns arrived at an Israeli hospital all alone. Now he’s on the road to recovery—and getting more visitors than he can handle.

Kobi Fuchs

Kobi Fuchs

Kobi Fuchs

Kobi Fuchs

Wanchai Monsana was admitted to Beersheba’s Soroka Hospital on Oct. 9, two days after he narrowly escaped Hamas’ massacre. Severely burned, he arrived barefoot, wearing little clothing, and lacking his wallet, money, or phone. Monsana’s coworkers—like him, from Thailand—were either murdered by Hamas or kidnapped and taken captive to the Gaza Strip. Monsana, 44, doesn’t speak Hebrew or English and, despite working for four years on farms in Israel, knew no one else in the country except his boss—and he wasn’t sure whether that man remained alive.

Monsana had nothing and was alone in Israel.

That changed in mid-November.

Monsana had been transferred on Oct. 10 to the burn unit at Sheba Medical Center, in Ramat Gan. An Israeli woman whose son was also in that hospital saw the Thai man there, with no visitors, and sent a WhatsApp message about him. Someone else’s Facebook post followed, and soon Israelis came by to see him and extend best wishes.

They haven’t stopped.

“People have been visiting all the time,” a nurse told me when I stopped by the hospital on Nov. 20.

So many Israelis have come, sometimes taking along their Thai workers, that a handwritten sign on Monsana’s door requests that he be left alone between noon and 3 p.m. to rest.

Monsana’s first visitors bought him a phone—two phones, in fact—and a wallet into which they placed 200 shekels (about $50). Others brought clothing and meals. Thai restaurants in nearby Tel Aviv have delivered lunches and dinners. A glance at a rolling cart beside his bed and a shelf at the back of his room near the nurses station revealed some of what people drop off: a Buddha statuette; cartons of soy milk; bottled water, juice, and soda; and packages of shrimp noodle soup and snacks, including Thai cookies.

A paper taped to a rail on Monsana’s bed provided the number of his bank account in Thailand to which donations could be wired. Monsana didn’t write it to solicit; an Israeli man and his Thai wife, Kobi and Chotika Fuchs, did. Not only those in Israel are sending money—so are Israelis living in Thailand.

On the afternoon of my visit, May Kaufman, a resident of Kibbutz Eyal in central Israel, deposited a homemade chocolate cake and chocolate chip cookies on the cart as her teenage daughter Gefen looked on. With the Kaufmans were two Thai men, Chanathip Nankratnok and Wanchai Phatthanaserikun, who work on their kibbutz. They’d just prepared a favored Thai dish, fried pork with basil, for Monsana. The men also carried a box of persimmons they’d picked that morning. Next time, they said, it’ll be avocados, which are soon to be harvested.

A nurse had told the four, along with myself and an Israeli visitor who speaks Thai, to rub their hands with a sanitizer before entering the room. That was to reduce the chance of Monsana getting infected.

As they sat down to talk with him, someone suggested taking Monsana outside to get some air. He agreed, the nurse nodded that it would be OK, and the visitors wheeled Monsana on his bed onto an elevator, descended one floor, and continued to a yard fronting the hospital.

It was the first time Monsana went outside since entering the hospital more than a month earlier.

“Israelis have shown much compassion and extended assistance to Thai workers who were affected [by] the conflict,” said Pimchanok Jirapattanakul, a consul at Thailand’s Embassy in Herzliya Pituach. “We have heard that some Israelis offered temporary shelter for Thai workers who had to leave their moshavim/kibbutzim due to the war. Many Israelis also visited the hospitalized workers, despite not knowing them personally. The Royal Thai Embassy believes that this not only reflects the generosity of the Israelis, but also the close friendship between Thailand and Israel at the people level.”

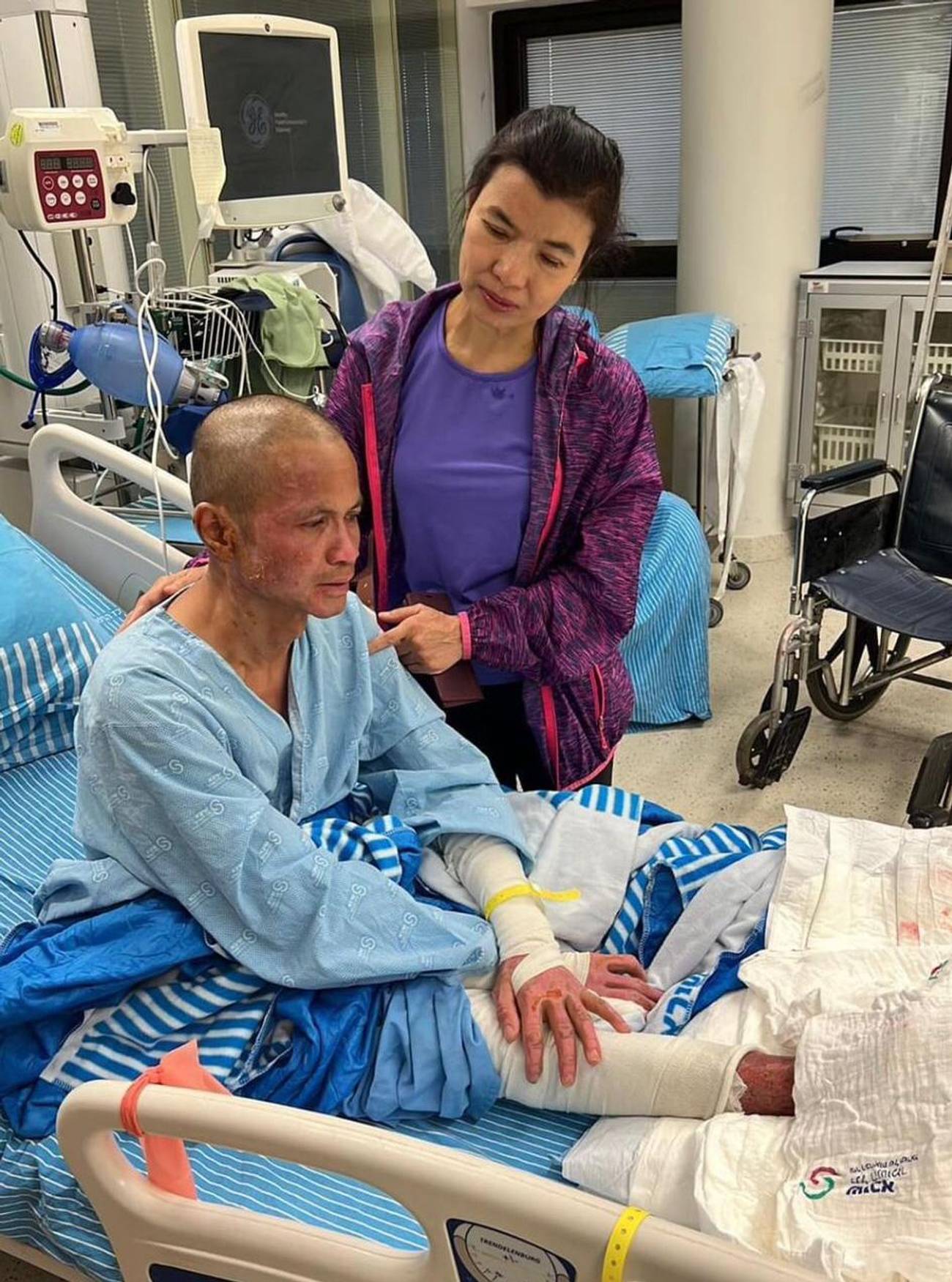

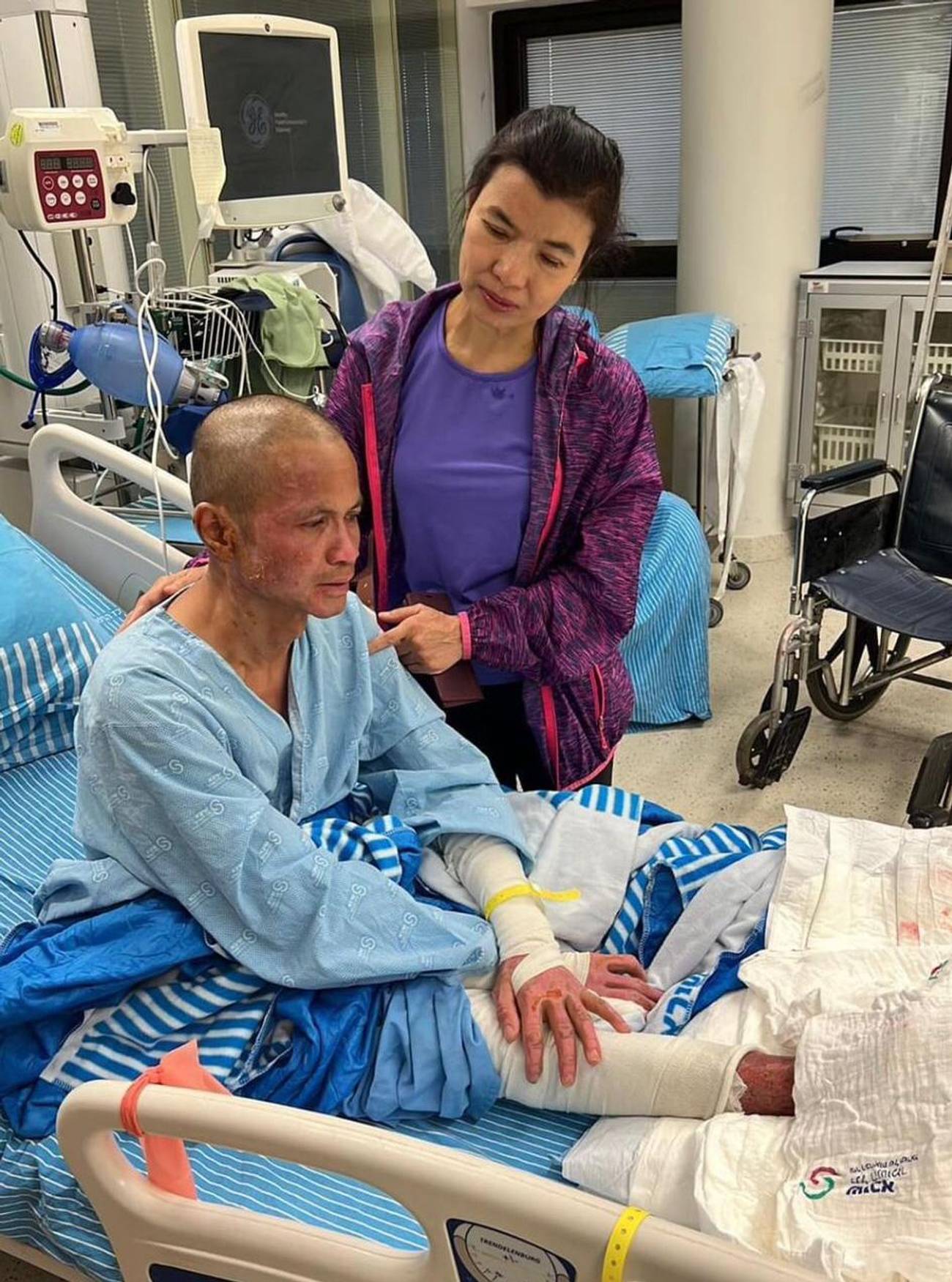

The right side of Monsana’s face and his right ear are burned. His arms are bandaged until just short of his fingertips. His legs are completely bandaged, too. His right toes and part of his right foot have been amputated.

Monsana was fortunate to survive. Hamas terrorists set fire that Oct. 7 morning to the barn in which he took refuge on Moshav Mivtahim, near the southern corner of the Gaza Strip. The terrorists sought to force out those in the barn to shoot them. Monsana heard gunshots when other Thai workers emerged from the flames, so he stayed put—for nearly two days. Finally, he ran barefoot and far—he doesn’t know how many kilometers—to a Thai friend. An ambulance eventually transported Monsana to Soroka.

He arrived there critically ill and in septic shock due to sustaining burns on 50% of his body, primarily his head and upper and lower extremities. He was intubated, underwent a debridement to thoroughly clean his skin, and then got a skin graft. At Sheba, he went through additional debridements and grafts, then the amputations.

Josef Haik, a physician who heads Sheba’s burn department, explained that the blood vessels that supply oxygen and nutrients to Monsana’s right foot and toes were badly damaged in the fire and that the injury was further compounded by trauma caused by his running barefoot over a long distance. Damage to his circulation was so severe that parts of the foot could not be saved, necessitating a partial amputation.

“It’s incredible that he survived. He’s brave and he’s very strong,” Haik said by phone on Nov. 24. The day before, Monsana walked at the hospital with the assistance of a physiotherapist. Haik hadn’t expected Monsana to be on his feet yet. By the second week in December, Haik said, Monsana could start physical therapy. Because of the amputations and to prevent excessive scarring, Monsana will need special shoes and clothing throughout his life.

Mandatory health insurance will cover Monsana’s medical bills. Israel’s National Insurance Institute and Thai agencies will compensate for his being out of work, Jirapattanakul said, adding that the embassy was informed “by relevant Israeli authorities that the Thai victims will receive the same level of compensation/benefits as those given to the Israelis.”

In his room at Sheba and during the 20 minutes outside, Monsana said little, even to his compatriots.

Monsana said he worked in the meat-processing plant and also picked potatoes at Moshav Tekuma, about 20 miles northeast of Mivtahim. Hamas murdered 20 of his Thai colleagues at Tekuma, he said. He’d been in Israel for four years, but had neither toured anywhere in the country—he said he had rarely left the moshav or its immediate surroundings—nor returned to Thailand on vacation. He’s married, has a 20-year-old son, a 10-year-old daughter, and an 8-month-old grandson. Is he in any pain? No. Has his boss visited him in the hospital? No. Have he and his boss been in touch since Oct. 7? Monsana said no, adding that he’s not sure if the man is still alive. (An Oct. 15 post on the plant’s Facebook page stated that the owners and their families survived Hamas’ slaughter. Multiple phone calls and texts to the phone numbers listed were not returned.) When a translator conveyed Gefen Kaufman’s remark that Monsana looks too young to be a grandfather, Monsana smiled slightly. He smiled again when Nankratnok held out cans of Leo, a Thai beer.

Thais and other foreign nationals are among the invisible victims of the Oct. 7 catastrophe. Newspapers and TV stations rarely cover them. In a Tel Aviv plaza known as Hostages and Missing Square, none of their relatives or colleagues is seen advocating for their liberation, as occurs for Israelis. They aren’t among the 240 or so kidnapping victims represented by placards displayed there and throughout the country.

But 36 foreign nationals were kidnapped along with Israelis on Oct. 7. Two are from the Philippines and one each from Nepal and Tanzania. In all, Hamas kidnapped 32 Thai nationals and murdered 40. (During the ongoing Hamas-Israel pause in hostilities, 16 of the 32 Thais and one Filipino were freed as of Nov. 28.) Three Thais remain hospitalized.

Prior to Oct. 7, 30,000 Thais worked in Israel, nearly all in agriculture; others were employed as restaurant cooks and construction workers. About 21,000 of the Thai agricultural workers remain in Israel, Jirapattanakul said.

Many continue to live and work in the Gaza-area kibbutzim and moshavim. Others were evacuated with Israelis elsewhere in the country.

Through early November, the embassy organized 35 repatriation flights totaling 7,470 passengers, and 1,500-2,500 others purchased tickets on commercial flights and left since the war began, Jirapattanakul said.

They generally come to Israel on five-year work visas. It’s common for a kibbutz with a departing Thai employee to replace him—most are men—with another Thai. Thousands more Thais live in Israel fairly permanently, with Thai nail salons and therapeutic massage centers a common sight in Tel Aviv. Some are married to Israelis and are on the path to citizenship.

One is Chotika Fuchs, an accountant and massage therapist from Nakon Si Thammarat in southern Thailand. She and her Israeli husband, Kobi, live in Rishon Lezion and visit Monsana about twice a week, ever since the lawyer who handles her citizenship application alerted them to the Thai man in Sheba’s burn unit.

She’s assisted him in such ways as buying bananas (a favored food of Monsana), measuring him for new clothes and laundering the clothes she bought as a sterilization precaution, and explaining why he had to sign a document allowing physicians to administer general anesthesia.

When the Fuchses visit Thailand in January, they’ll go to Monsana’s home near Nongksai to reassure his family that, despite what befell him in the country, Israel is taking good care of him.

“People in Israel have a very good heart,” Chotika Fuchs said. “I’m happy to see how they feel toward the Thai people.”

Hillel Kuttler, a writer and editor, can be reached at [email protected].