Wading in Deeper

While I was planning my bar mitzvah, my non-Jewish friends were planning their cotillions

It took me a few weeks of getting dropped off and picked up at school to see that something besides our last name was different here. Then it struck me. We drove up each day in our big new Buick, while my classmates arrived in old Ford station wagons with wood trim on the sides, or older sedans painted in sedate colors—sometimes with thin red racing stripes along their length (to match the stripes on the Social Register?). Some of their cars had subtle monograms on the doors, and many sported college or club decals on the rear window. Most of their cars had license plates with no more than four numbers, some with the year their father had graduated from Harvard or Yale—like 1927. Our license plate, on the other hand, was six random numbers signifying nothing, other than the fact that we hadn’t come over on the Mayflower.

Dammit, Mom! I wanted to say. Why didn’t you do a little homework before you sent me here, and at least find out what kind of car we’re supposed to drive, and where you order the monograms and decals? You needed to know the basics, I thought, if you were trying to barge into their society; you couldn’t simply mail in an application to one of those fancy schools. We looked like a bunch of know-nothing immigrants right off the boat. There I was, a first-generation American, and they had been here for centuries. Their furniture had been here longer than we had.

Actually, to be honest, the car part wasn’t her fault. We had to buy Buicks. Everyone in the family had to buy Buicks because my Uncle Murray owned a big Buick dealership in Chelsea, and on the back of every car he sold he stuck a small, raised chrome sign that read “by Ullian,” This was about as far as you could get from the understated elegance the Yankees had perfected over the course of three hundred years.

There were plenty of other things that set me apart as well. When I boarded at prep school, my father would occasionally come to visit in the afternoon and would always stop at the G&G Delicatessen on Blue Hill Avenue (a previously old Jewish Boston neighborhood) to bring me a hot pastrami sandwich with a kosher half-sour pickle, a cream soda, and some chocolate-covered Halvah. He would drive up to the front porch of my dorm, Robbins House, in the enormous Buick, cigar in his mouth, wearing his gray fedora with pinched indents like the one Harry Truman sported.

Now that I think of it, my father looked a bit like Harry Truman, complete with the wire-rim glasses.

The wood-paneled walls of our dormitory, oiled and polished for more than a hundred years, had never been assaulted by a pastrami sandwich and a half-sour pickle, and seemed to suck it all in, leaving the dorm to smell like a Jewish delicatessen.

I smell something funny, I imagined each student coming through the front door would exclaim.

I do too.

And then a mob of them would follow the scent up the stairs, down the hall, and stop in front of my room only to discover me sitting on the edge of my bed, secretly scarfing down my alien sandwich and garlic-riddled pickle.

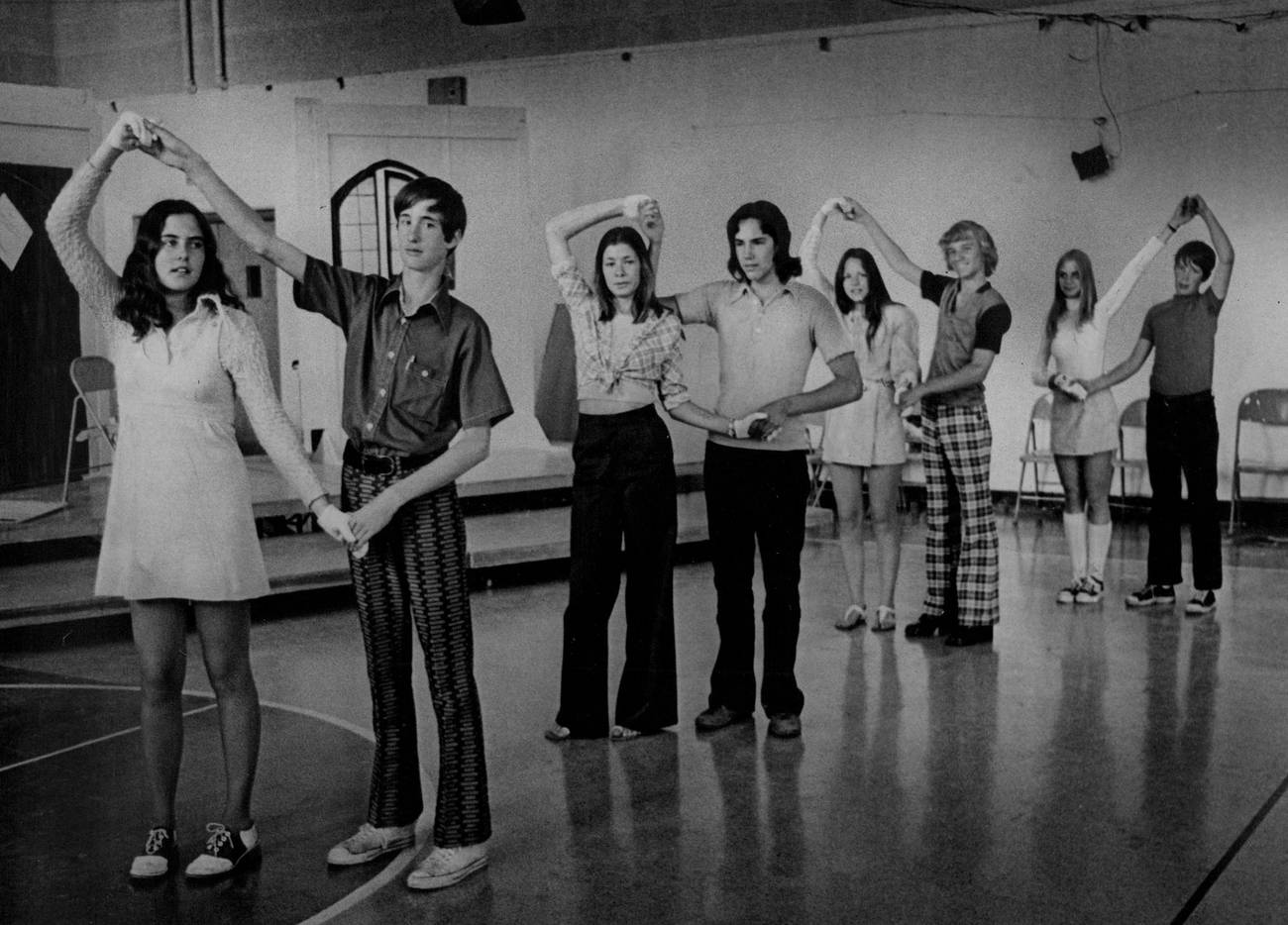

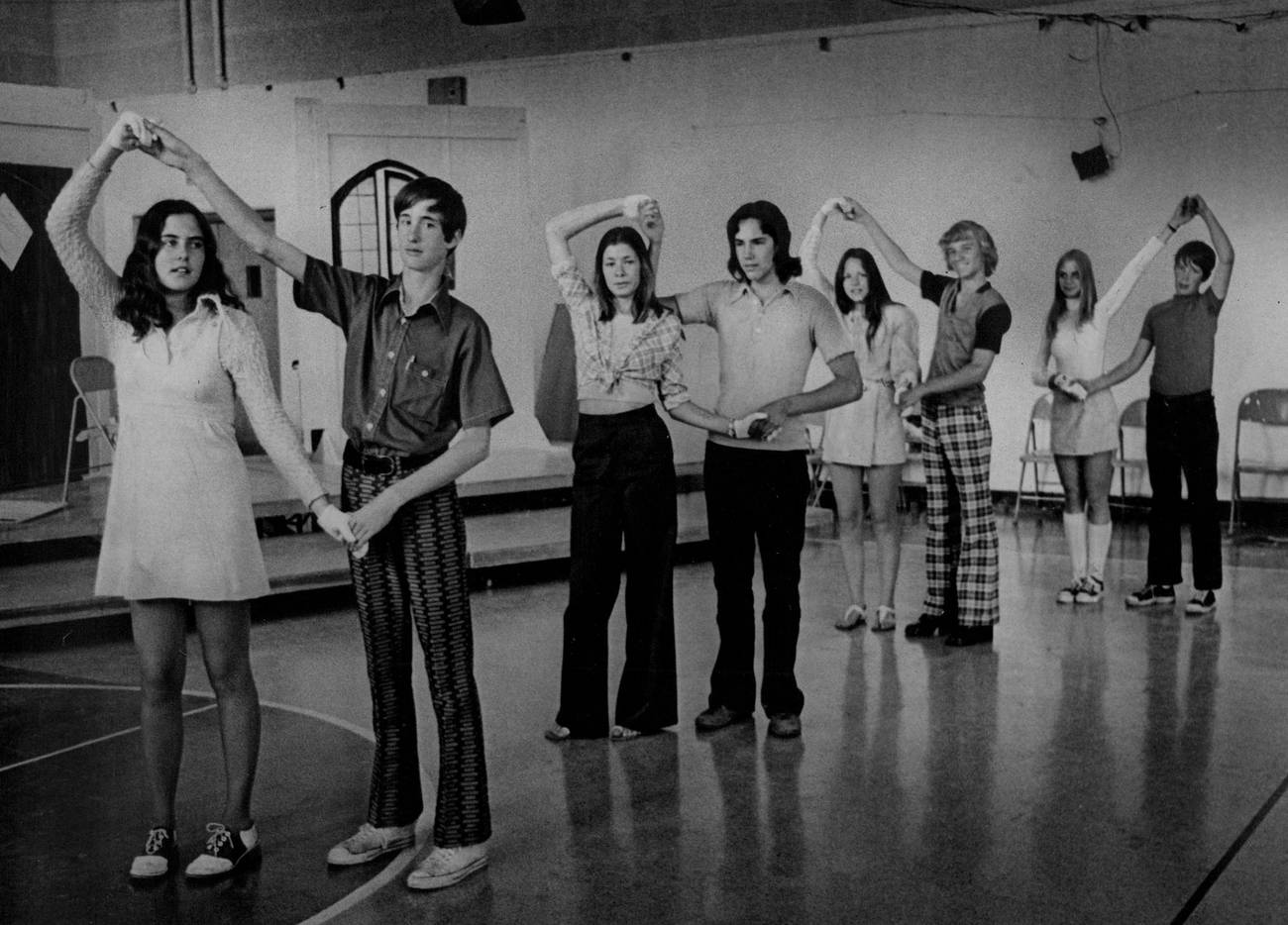

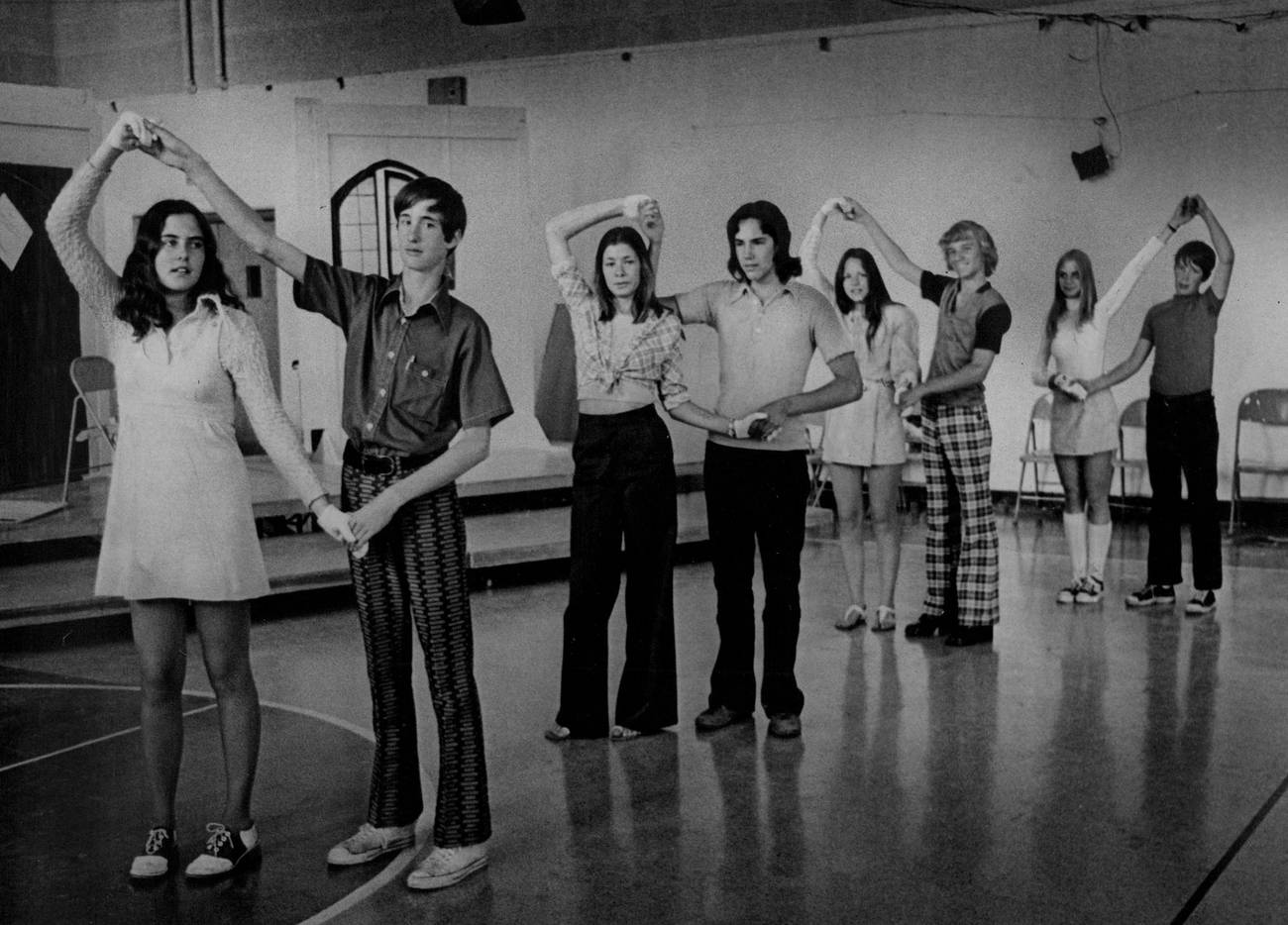

Life at school in the eighth grade grew more intense as the cotillions and the parties got closer and my classmates prepared for their older sisters’ and cousins’ coming-out events. My Bar Mitzvah was also looming closer, but lucky them—all they had to do was learn the foxtrot. I had to learn Hebrew and read it from a four-hundred-year-old Torah scroll while holding a sterling silver place keeper with its pointy finger on the end. And I had to accomplish this in front of an entire temple packed with friends and relatives, all waiting for me to screw up.

A week before my big day there was a dress rehearsal in the temple. I was on the bimah (altar), standing behind the massive pulpit, wearing my yarmulke and tallit (skullcap and prayer shawl), and when I looked out into the cavernous sanctuary where the principal was seated, I got dizzy and, boom, I hit the floor.

“Where did he go?” the principal yelled as he ran up the stairs onto the bimah to see what had happened. He found me sprawled out behind the pulpit, my tallit covering my face, my yarmulke askew, as he frantically tried to find a pulse.

When I recovered and finally got home, I ran up to my room. How was I going to get up there behind that pulpit the following Saturday and survive? In addition to my Torah reading, I would have to make a speech in English, discussing the meaning of the Torah portion I was about to deliver. The English part was not the problem, as I had already written it out with the help of my Bar Mitzvah tutor and had practiced it many times in front of the mirror over my bureau. But my Hebrew was weak.

The Torah scroll doesn’t even include the vowels that usually appear under the Hebrew letters, something I am sure is intended to drive Jewish kids crazy. Try to learn English without any vowels! The scribes must have thought it was too much extra work to add the dots, and figured that if you had paid attention in Hebrew school, you would know the words and wouldn’t need the dots.

Well, I didn’t know the words, and it was making me very anxious. Couldn’t I just fake it like Sid Caesar in a TV shtick, where he would mimic a foreign language, making it all up but injecting a few English words here and there so the audience would understand what he was talking about? The word endings just needed to sound guttural, like someone clearing his throat. After all, this was a Reformed (modern, liberal) temple; most of the congregants even ate lobster.

Converting to a foxtrot religion with country clubs and tennis courts sounded pretty appealing to me at that moment.

Somehow, I made it through the service without fainting, and only one cousin found fault: “Pretty good, Arthur, but there were a few mistakes.”

So here, take back your fountain pen, I wanted to say to the critic. I had made it through, and that was good enough for me.

Surely Christianity is far simpler. In the middle of the first century, when Paul and his followers were beginning to convert pagans to his new religion, he knew it had to be accessible, so he made it “Jewish light.” He kept the Ten Commandments, for instance, but circumcision was out. How could you possibly expect a guy more than eight days old to sign up for that?

Keeping a Kosher home, which required two sets of pots and pans, two sets of dishes, two sets of everything just to keep the milchig (dairy) and the fleishig (meat) separate, was too expensive and too complicated. So that was out.

Studying and reading the Torah, debating the meaning of every word, phrase, and paragraph, understanding the hundreds of laws governing daily life and trying to keep those laws ... it was way too much homework and most pagans were illiterate anyway. So those things were out too.

And why not be able to achieve salvation and a terrific afterlife just by accepting Jesus, who so considerately died for your sins?

While you’re at it, Paul, make the Christian holidays coincide with the familiar Roman ones, like assigning Christmas to December 25, the date Julius Caesar had already declared a holiday in 46 BCE to mark the winter solstice, complete with the lighting of candles. (The Romans were off by a few days; the solstice is actually December 21.)

After the Bar Mitzvah, the tradition was to host a brunch in the temple’s social hall and invite everyone attending the service, even those who didn’t know the Bar Mitzvah boy. (That was a clever way to get people to come to temple on Saturday morning, kind of like the Salvation Army, who invite the homeless to a worship service and, if they sit through it, give you a cup of soup and sandwich.) But you had to go all out at an Oneg Shabbat (delight of the Sabbath); a huge spread was expected. There would be every kind of bagel, three kinds of cream cheese, hand-cut belly lox, an enormous whitefish, sablefish, green salads, egg salads, herring, and everything you would ever want from Katz’s fifteen-foot-long refrigerated deli case (if you weren’t paying). Then there was Danish and rugelach (pastry roll-ups with cinnamon and nuts or apricot jam) for dessert.

Later that night, you’d have a big catered party at your home, where you served more of the traditional Jewish gourmet foods: knishes, kishke, kugel, chopped liver, shrimp cocktail (remember, we weren’t kosher), and more.

And that was it. Done! I was now a man at thirteen.

All during this time, I heard only scraps of information about the cotillions that were beginning to take place. My classmates had to be aware I was never invited, and I imagine they were embarrassed to talk about these parties in front of me. But in my fantasies, they resembled what I thought went on in Masonic temples—dry ice pumping smoke into the air, back-lit with colored spotlights, and secret rituals taking place.

What I eventually gathered was that each beautiful blond debutante, dressed in a long white gown, would walk down the center aisle of an elegant banquet hall on the arm of her father. She would be trailed by her escort, one of my classmates, who had been practicing this ritual since the fourth grade and now was lending his arm to the girl’s proud mother.

Arrayed in front of them, in my imagination, was a grand stage, carpeted in red, with four or five old grande dames seated in chairs fit for Queen Elizabeth or, better still, Queen Victoria, dressed in faded, fifty-year-old debutant gowns, which were shortened as these stewards of society shrank in size. As each debutante approached, the old ladies would rise, smile approvingly, and tenderly touch the hand of the white-gloved debutant.

A year or two later, the coming-out parties began, and I assumed they had to be a whole lot more fun than our knish parties, but I really didn’t know since Miss Hall had been correct to assume I would never be invited. She would have been shocked to discover that I did crash a few with friends who also hadn’t been invited but knew about the events through the preppy grapevine. These parties were held at local country clubs and included big-name bands, dancing, and open bars, but almost nothing to eat. Apparently, the idea was that with enough to drink, you didn’t miss the food.

One party stands out. My friend Rabbit (I still don’t know where that nickname came from) heard of a party he hadn’t been invited to. He was spending the weekend at my home (boarders could leave campus if they were staying with students who lived in the area). This particular party was being held in one of the most exclusive tennis and cricket clubs in the world—so exclusive, Jews were barely allowed to drive on the same street, let alone enter the club.

“We can crash it, but I’ll need a tux,” Rabbit whispered to me after dinner.

“My father has an old one and he won’t mind because he won’t know,” I whispered back.

We got dressed and off we went. We must have been sixteen or seventeen at the time, because I remember that we drove ourselves in one of my parents’ cars. It was my first time at one of these things, and even without the advantage of being prepped by Miss Hall on how to be a model guest, I felt certain I could wing it. I thought that getting in would be the toughest part, but to my surprise it was easy. The nice thing about WASPs is that they are far too polite to inquire if you have an invitation. They greet you with a pleasant smile, and you’re in.

Was that a Jew we just let in? I imagined the two women greeters saying to each other. My paranoia was running wild as I anticipated the tap on the shoulder asking me to leave. That would have done it. I’d never be able to show my face at school again. Everyone else belonged to the same clubs or attended the same church, so they looked familiar to each other. But of course, they didn’t know me from Adam. Thankfully, the tap never came. After a while I began to relax and breathe normally again. I followed Rabbit to the bar, ordering what he ordered.

That club was and still is so well fenced you can’t see any part of it from the street. Once inside, I found that it was not splashy, but stately and comfortable. I noticed all this while trying not to look around as if I had just gotten off a bus from Milwaukee. I took my drink and walked toward the grand covered balcony, a structure furnished in old wicker that was covered in traditional green-and-white striped fabric, looking like it came right out of the Newport Tennis Casino. Here on the balcony was obviously where members could sit overlooking the impeccably groomed grass courts, drinking martinis and watching impeccably groomed members play in their dress whites.

This party was nothing like any Bar Mitzvah I’d ever been to. There was lots of liquor and precious little to eat (Jewish parties are exactly the reverse). Rabbit got smashed and eventually collapsed in the circular driveway right by the front door. Getting up, he tried leaning against the front wall to steady himself, and then proceeded to throw up all over my father’s tuxedo.

I began to notice that there was a distinctly Yankee look, made even more prominent by the outfits they wore. (Southerners call all Northerners Yankees, but Yankees are what New Englanders call the descendants of the earliest immigrants to America—the English-born Pilgrims and Puritans of Mayflower and Plymouth Rock fame.) But it wasn’t only the clothing they wore. I tried it all—the pink shirts, polo shirts with up-turned collar, the nearly transparent framed glasses, even the slightly English-sounding Harvard “lock-jaw” accent. There wasn’t much more I could do to replicate the look. It was the healthy, glowing, tanned complexions and classically formed bodies, nothing like the ones I saw slathered with Coppertone around the swimming pool at the Fontainebleau in Miami. There was no way I was ever going to look like Michelangelo’s well-muscled David, standing in the piazza in Florence; nor was any Jewish guy I ever knew. Actually, the real David in the Bible was probably a scrawny little Jew like the rest of us.

My classmates’ fathers not only looked more athletic than my father, but they also looked younger, no matter what their age. Some seemed to have a slight limp, perhaps from an old hockey or football injury, which only enhanced their rugged image. They all played a solid game of tennis, sailed in the summer, skied in winter, and enjoyed telling what they thought were hilarious stories about Salty or Poopsy or Bunny falling off the porch after one too many. A lot of my friends’ parents seemed to have one of those funny nicknames. For the longest time I thought they were talking about their dogs.

Once, in art class, we looked at a slide of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper and discussed all the arty stuff, like the angles of the walls showing perspective, the symbolic meaning of the scene in the windows in the background, how Jesus is placed at the center—all those details that take up class time. But my attention was drawn to something else. What struck me was that Jesus and the apostles looked exactly like my classmates, which is to say they had light skin and straight, thin noses, some even slightly turned up, which happened to be the preferred style for young Jewish girls getting nose jobs in the 1950s. All except Judas. He was the apostle who betrayed Jesus for thirty pieces of silver and is seen sitting two seats to the left of Jesus, clutching his money pouch. Judas’s complexion is decidedly darker than the rest, and from my vantage point in the classroom, I would swear that his nose looked Jewish.

I was thinking of a question I could ask the teacher (to make him think I was a serious student). But the question that popped into my head made me start to laugh so hard that, trying to hold it in, I couldn’t have asked it if I’d wanted to:

Sir, I think Leonardo may have got it all wrong. After all, Jesus and all the apostles were Jews, but they don’t look Jewish to me, unless da Vinci was making the point that when you get baptized and became a Christian, you get a new nose as a bonus. Is that right, sir?

Later, I heard this very issue addressed on National Public Radio, confirming my schoolboy thoughts. Robert Wallace, in his book The World of Leonardo, 1452–1519, found that da Vinci had spent a lot of time looking for models of young men with faces that exhibited innocence and beauty, but when it came time to find a model for Judas, he found just the right man imprisoned in a Roman dungeon. This person had a dark complexion, scars, and unruly hair covering part of his face: all in all, a sinister-looking fellow you wouldn’t want to meet on a dark street.

Anyway, what I had thought was so funny about the painting vanished as my teacher continued: “As you look at the painting carefully, the apostles aren’t eating; they’re all talking excitedly, gesturing and pointing. Does anyone know why?”

No one raised their hand, so he said, “Jesus had just told the apostles that one of them would betray him.”

I held my breath, waiting for what I knew was coming. Again, I was the villain in the room. And I thought art class was supposed to be fun.

I had heard these words in chapel and now I was hearing them in art class too. Painted in 1498, The Last Supper has been viewed by millions of people. It is one of the most famous artworks in history, and everyone is reminded of the original slur against the Jews contained in Matthew 26:21 (King James Version used throughout this book): “Verily I say unto you, one of you will betray me.” The same words are repeated in the communion section of the mass as well: “On the night Our Lord was betrayed ... He took bread.”

No matter what class I went to, there seemed to be some evil Jew lurking in the curriculum.

Excerpted from Matthew, Mark, Luke, John…and Me: Growing Up Jewish in a Christian World by Arthur D. Ullian. Copyright © 2020 by Arthur D. Ullian. Excerpted by permission of Bauhan Publishing. All rights reserved.

Arthur D. Ullian is the author of Matthew, Mark, Luke, John…and Me: Growing Up Jewish in a Christian World (Bauhan Publishing).