The Bold Jewish Woman Who Created Barbie

How Ruth Handler dreamed up the doll that feminists loved—or loathed

Dinello/The People/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Dinello/The People/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Dinello/The People/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

Dinello/The People/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

I admit it: I’m a raging feminist anxiously awaiting Barbie, the rom-com due out July 21 that director Greta Gerwig co-wrote with Noah Baumbach. Growing up the only girl in a Midwest clan of boys, I had 68 Barbies, plus the Dream House and convertible. Barbie’s multiple professions, pad, and wheels inspired my early escape to college and an eclectic, big-city career. It’s no wonder, since Ruth Handler, Barbie’s inventor, was a Jewish female trailblazer whose doll reflected her own life.

Ruth was the 10th child of Polish immigrants Ida and Jacob Moscowitz, who came to America to escape antisemitism—and his gambling debts—landing in Denver. In 1916, when Ruth was 6 months old, her 40-year-old mother needed surgery. Ruth’s big sister Sarah and her husband, Louis Greenwald, took Ruth home—and kept her, basically raising her as their only child, since Ida had nine other kids to look after and less money. All her female relatives had to work, Ruth wrote in her 1994 memoir Dream Doll. She worked as a soda jerk at Sarah’s drugstore and secretary for her lawyer brother.

Ruth met Elliot Handler, her future husband and business partner, at a B’nai Brith dance when she was 16. But she stayed independent for several years: Ruth’s family gave her a 1932 coupe and let her work as a stenographer at Paramount Pictures, living in an LA apartment with female friends (inspiring Barbie’s modern lifestyle). At 24, Ruth proposed to Elliot. The creator of myriad miniature bridal gowns wore a borrowed dress to her 1938 wedding. She had two children: Kenneth and Barbara, whose names later inspired the names of the dolls she created—something her real-life children resented.

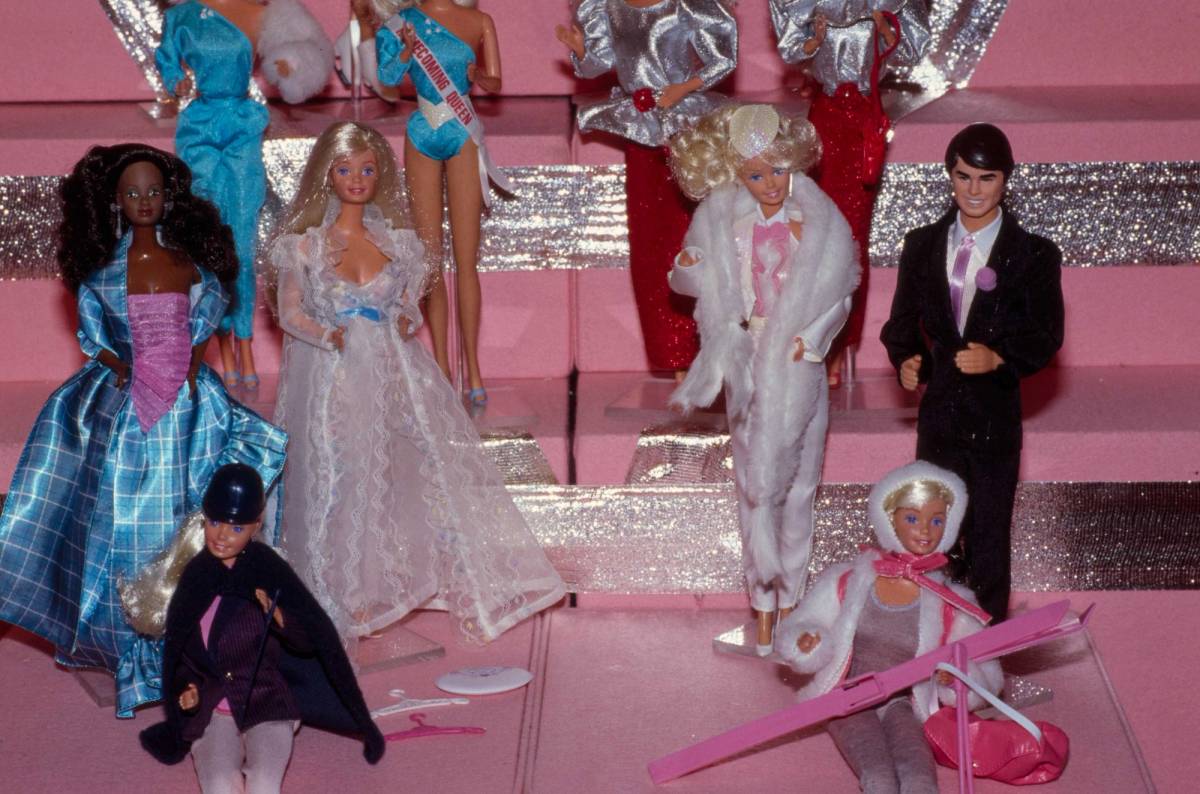

Matt Campbell/AFP via Getty Images

In 1945, Elliot Handler and his business partner Howard Mattson combined their names to form Mattel; Ruth became the company’s president, and she’s the one who came up with Barbie. She rejected baby dolls that indoctrinated girls into motherhood, like Betsy Wetsy, Tiny Tears, and Chatty Cathy, trying to replicate the grown-up paper dolls her daughter preferred, in plastic. But she was told adult dolls were too expensive to produce. Then, shopping in Switzerland in 1956, she spotted the “adult-style” doll called Lilli—a sex toy copying a German cartoon of a blond good-time girl exchanging sex for stockings—according to M.G. Lord’s 1994 Forever Barbie. Ruth decided to turn the European bachelor-party gift into an American girls’ toy. And Barbie was born.

Ruth consulted Ernest Dichter, a Viennese psychologist who researched products, like the convertible, imbued with sexual cachet. Moms viewed Barbie as cheap and vulgar, he found. (No wonder I loved her!) Yet daughters hoped to emulate Barbie’s glamour and sexiness. Debuting in a striped bathing suit at the 1959 New York Toy Fair, Barbie came as both blond and brunette, like Ruth.

Male retailers questioned why Ruth gave the plaything breasts, insisting girls wanted infant dolls. “They want to pretend to be older girls,” Ruth argued, deciding the sophisticated doll would encourage girls to imagine grown-up possibilities. (Indeed, I’m sure Barbie’s myriad professions paved the way for my subsequent employment as receptionist, waitress, confessional poet, secretary, paperback book critic, and part-time teacher.)

Barbie’s first TV commercial aired during the Mickey Mouse Club show, broadcast to kids over the summer. Girls were riveted by runway dolls singing, “Someday I’m gonna be exactly like you … beautiful Barbie,” and pushed their moms to buy the $3 figurine. Ruth changed the consumer from parent to child, giving girls agency. Some saw advertising to children as sly. Others felt it empowered females to pick their own dolls. That first year, Mattel sold 350,000 Barbies. Mattson sold his shares. Ruth was already Mattel’s president when it went public in 1960.

I fear critics who narrowly focused on the doll’s measurement and materialism missed the bigger picture. Barbie was my dream mentor, as a budding liberal reared in staid suburban Michigan. In 1962, she was working as a teen model, with her own car and home. Ruth, an inspired businesswoman, gave her shockingly prescient autonomy; it wasn’t until 1974 that American women were allowed to have a credit card in their name to get an automobile, loan, or mortgage without a father or husband co-signing.

Barbie was also a singer, nurse, fashion designer, college grad, executive, and astronaut. Still, girls begged for her boyfriend. Male dolls usually tanked. Hasbro’s G.I. Joe was called an “action figure,” “frog man,” or “fighting man,” as boys wouldn’t touch dolls. “The sales force was forbidden to use the term doll—if anyone referred to it as a doll they were fined,” a Hasbro employee told Robin Gerber, author of 2010’s Barbie and Ruth. Ruth recalled that when her daughter was playing with paper dolls, she needed a male version for dates and proms. In 1961, Ken debuted as Barbie’s boyfriend, marketed to young females as Barbie’s romantic interest—not to young males as a stand-alone toy. Though Ken was a hit, Ruth ensured he was an accessory. Barbie remained the star.

Library of Congress

Mattel sold Barbie wedding gowns, but Ken was her boyfriend, never husband. Less enchanted with motherhood than work, Ruth refused to let Barbie have a baby. Instead, Barbie’s friend Midge married Allen and a “Happy Family Line” included a pregnant Midge with a magnetic detachable stomach holding a small body inside. After parents complained that she encouraged teenage pregnancy, Midge was discontinued. Then, dumping her mate and kids, Midge reemerged solo.

Barbie’s closest baby brush was 1963’s “Barbie Babysits” ensemble with phone, bottle, pink bassinet, and infant. Nearer to Barbie and Ruth’s glam image were her sunglasses and mini-books How to Get a Raise, How to Travel, and How to Lose Weight (which contained two words: “Don’t Eat!”). Enraging leaders of the women’s movement, the scale on the 1965 Sleepytime Gal slumber party was set on 110 pounds, though the American female averaged 140. If Barbie had been 5-foot-6, she’d measure 39-18-33, with a size 3 shoe and a body-fat percentage so low she couldn’t menstruate, a symptom of anorexia. The percentage of real women that size was under 1 in 100,000.

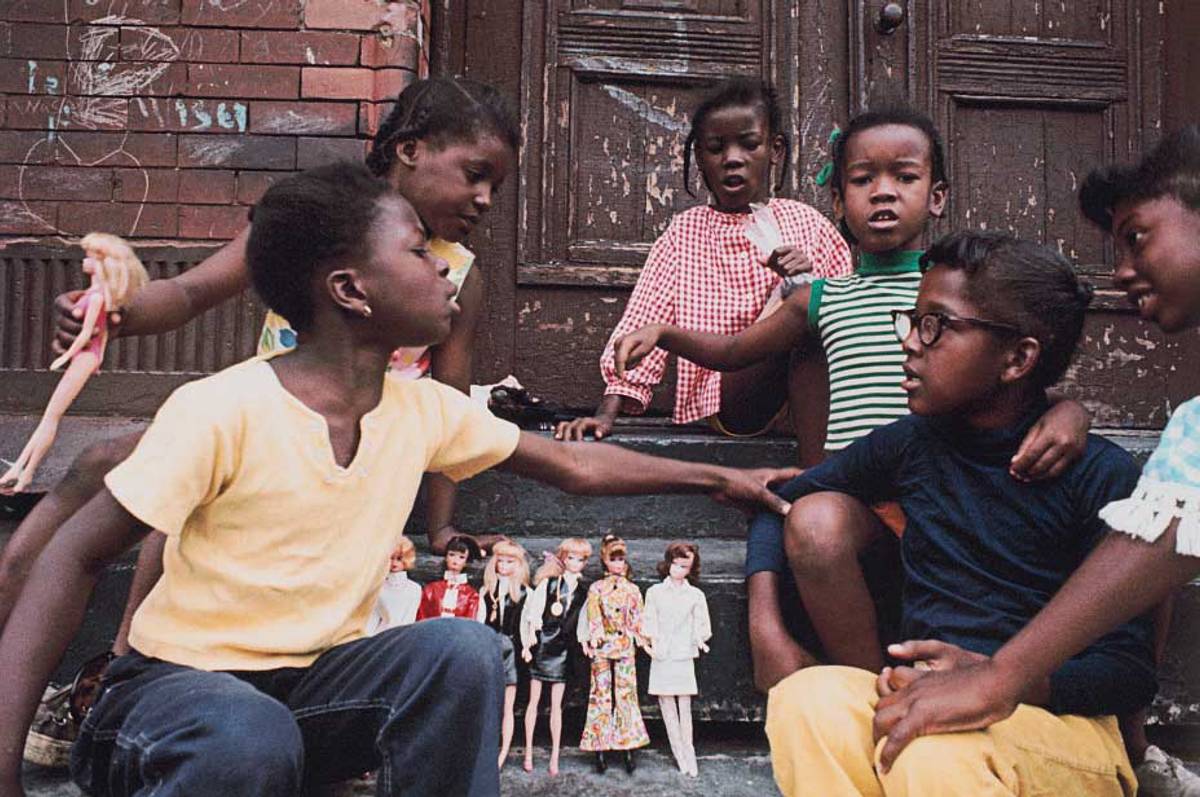

Meanwhile, Ruth’s new ideas led to other flops: 1970’s “Growing Up Skipper,” who simulated puberty. Flicking her wrist, she’d grow an inch taller. Rotating her arm, breasts popped out from her rubber chest. This led to a storm over the unintentionally perverted doll. With Nabisco, Mattel tried “Oreo Fun Barbie,” who wore a jacket decorated with cookies and carried an Oreo-shaped purse. Although Ruth had experienced antisemitism and intentionally added a Black doll in 1968 during U.S. race riots, the dolls—who came with white or black skin—caused complaints that the term “Oreo” was derogatory. They were recalled.

A 3-foot-tall “My Size Barbie,” with wedding dresses that fit the doll and her girl owner, tanked. To include disabled kids, Mattel tried “Share a Smile Becky” with a pink wheelchair that wouldn’t fit in Barbie’s home or car; Becky’s long hair tangled in the wheels. (A shorter haired version was tossed, too.) “Cool Shoppin’ Barbie” had a clothing store with cash register and MasterCard. Parents feared she encouraged irresponsible spending; the contract with MasterCard wasn’t renewed, making her a Smithsonian collectible.

At her lowest point in the 1970s, Ruth and four other employees were indicted for inflating sales records to influence Mattel stock. Claiming innocence, Ruth took the fall, not Elliot. Leaving Mattel, she paid $57,000 in reparations, served five years’ probation and did 500 hours of charity with Foundation for the People, helping others on probation reenter the job market.

When Ruth discovered a lump in her chest, a mastectomy left her feeling “de-womanized.” Unhappy with doctors’ suggestions that she stuff her empty bra cup with stockings, and disappointed with a $350 custom breast by a craftsman of artificial body parts, Ruth launched a new company in 1976. Nearly Me produced comfortable prosthetic mammaries in 30 sizes, 30A to 42DD, for $98 to $130. It was Ruth’s second phenomenon. In her 60s, she led a sales team of mostly middle-aged cancer survivors, fitting former first lady Betty Ford after her surgery. Although discussing the disease was taboo, Ruth spoke out for early detection, doing a “strip act,” removing her blouse for a People photographer, demonstrating similarities between the real and fake boob. On The Dick Cavett Show, she asked Cavett to feel her up on national TV. He obliged. “It seems my life has been going from breast to breast,” she joked.

Library of Congress

In 1993, Barbie-aholics craved a “cooler” Ken. “Earring Magic Ken” had blond highlights, lavender vest, earring, and necklace with a circular charm. Gay men made him the best-selling boy doll in Mattel’s history. Dan Savage’s syndicated sex column insisted Ken’s necklace was a cock ring, shocking family-friendly Mattel, which nixed Earring Magic Ken. Privately, Ruth was more liberal. According to Gerber’s book, she supported her son Ken when he contracted AIDS from a relationship with a younger man in Ecuador. According to Ruth’s memoir, her son remained happily married to Suzie, his childhood sweetheart, for 30 years, until his death; newspapers reported that 50-year-old Ken died in 1994 of a brain tumor.

While mourning, Handler met Jill Barad, Mattel’s new president, at a Jewish charity event. Their “We Girls Can Do Anything” campaign pushed Barbie’s achievements in 200-plus careers. After 20 years out, Ruth was back at Mattel and United Jewish Appeal’s first ever “Woman of Distinction.”

Sexual politics in the 1990s were complicated. Teen Talk Barbie’s voice box was programmed to say, “I love shopping,” “OK, meet me at the mall,” “Will we ever have enough clothes?” “Math class is tough,” and “Let’s plan our dream wedding.” Women’s groups claimed it undermined girls. Barbie’s Liberation Organization, performance artists combating gender stereotypes by “culture jamming,” performed “surgery” on 300 Teen Talk Barbies and G.I. Joes in New York and California. They switched Barbie’s voice box with G.I. Joe’s, so the bombshell proclaimed, “Eat lead, Cobra!” “Attack!” and “Vengeance is mine!” while the macho warrior enthused, “Let’s plan our dream wedding.” Reverse shoplifting, they put the trans-voiced dolls back on the shelves with the stickers “Call your local TV news,” to get press. The company withdrew the offensive phrases, offering customers a doll exchange.

A 1994 Simpsons episode parodied the hacking: Lisa bought a new talking Malibu Stacy who said, “Don’t ask me, I’m just a girl,” and “Thinking too much gives you wrinkles.” Lisa found the doll’s creator, Stacy Lovell (voiced by Kathleen Turner), who—like Handler—had been laid off from the doll company she founded. A new doll Lisa Lionheart espoused Gertrude Stein but mall girls preferred the talking Malibu Stacy.

Barad “built the Barbie doll into a $1.8 billion global powerhouse,” said The Wall Street Journal, but overexpanded. In 2000, Mattel’s stock collapsed. At 48, Barad slipped out with a $50 million golden parachute. Handler died in 2002 from colon cancer, leaving behind her husband of six decades. The New York Times blared, “Ruth Handler, Whose Barbie Gave Dolls Curves, Dies at 85,” lauding Handler’s invention as an icon of U.S. popular culture.

In 2016, Mattel launched new Barbies with four body types, seven skin tones, 22 eye colors, and 24 hairstyles, making the dolls less skinny and white with tall, petite, and curvy sizes, and body types for Ken: slim and broad. Their “Sheroes” line recreated Diane von Furstenberg, Emmy Rossum, Iris Apfel, and Olympians Aly Raisman and Anat Leilor as the first explicitly Jewish Barbies.

Though the brand was still doing $1 billion annual sales across 150 countries and 92% of American girls owned a Barbie, thanks to her affordable $3 to $10 price, the doll’s figure remained controversial. Mattel’s general manager received death threats over Barbie’s body. In Andrea Nevins’ 2018 documentary Tiny Shoulders: Rethinking Barbie, Gloria Steinem and Roxane Gay insisted Barbie was disproportional, promoting skinniness. On Time magazine’s cover, a curvy Barbie in a black dress sporting “meat on her thighs, a protruding stomach and behind” was captioned: “Now can we stop talking about my body?” Feminists applauded. One imagines Handler would, too.

Yet videos showing little girls playing unattended with the heavier doll at Mattel showed a 6-year old singing, “Hello, I’m a fat person, fat, fat, fat” as playmates laughed. A shy girl spelled it “F-A-T.” New Mattel President Richard Dickson told Time, “Ultimately, haters are gonna hate.”

While sales of Barbie were down last year, the buzzy Barbie movie proves that Ruth Handler’s creation has endured, remaining our hottest little lightning rod. I’m glad I kept all my dolls and even bought an independent Israeli designer’s Tefillin Barbie—complete with tallit, siddur, and Ruth’s radical, revolutionary spirit to change the world.

Susan Shapiro, a Manhattan writing professor, is author of several books her family hates like Barbie: Sixty Years of Inspiration, Five Men Who Broke My Heart, The Forgiveness Tour, and her writing guide, The Book Bible. Follow her on Twitter at @Susanshapironet and Instagram at @profsue123.